Fall/Winter 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mississippi-State of the Union

MISSISSIPPI-STATE OF THE UNION DURING THE PAST several years in which the struggle for human rights rights in our country has reached a crescendo level, the state of ~ississippi has periodically been a focal point of national interest. The murder of young Emmett Till, the lynching of Charles Mack Parker in the "moderate" Gulf section of Mississippi, the "freedom rides" to Jackson, the events at Oxford, Mississippi, and the triple lynching of the martyred Civil Rights workers, Chaney, Schwerner and Goodman, have, figuratively, imprinted Mississippi on the national conscience. In response to the national concern arising from such events, most writings about Mississippi have been in the nature of reporting, with emotional appeal and shock-value being the chief characteristics of such writing. FREEDOMWAYS is publishing this special issue on Mississippi to fill a need both for the Freedom Movement and the country. The need is for an in-depth analysis of Mississippi; of the political, economic and cultural factors which have historically served to institutionalize racism in this state. The purpose of such an analysis is perhaps best expressed in the theme that we have chosen: "Opening Up the Closed Society"; the purpose being to provide new insights rather than merely repeating well-known facts about Mississippi. The shock and embarrassment which events in Mississippi have sometimes caused the nation has also led to the popular notion that Mississippi is some kind of oddity, a freak in the American scheme-of-things. How many Civil Rights demonstrations have seen signs proclaiming-"bring Mississippi back into the Union." This is a well-intentioned but misleading slogan. -

Cultural Resources Overview

United States Department of Agriculture Cultural Resources Overview F.orest Service National Forests in Mississippi Jackson, mMississippi CULTURAL RESOURCES OVERVIEW FOR THE NATIONAL FORESTS IN MISSISSIPPI Compiled by Mark F. DeLeon Forest Archaeologist LAND MANAGEMENT PLANNING NATIONAL FORESTS IN MISSISSIPPI USDA Forest Service 100 West Capitol Street, Suite 1141 Jackson, Mississippi 39269 September 1983 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page List of Figures and Tables ............................................... iv Acknowledgements .......................................................... v INTRODUCTION ........................................................... 1 Cultural Resources Cultural Resource Values Cultural Resource Management Federal Leadership for the Preservation of Cultural Resources The Development of Historic Preservation in the United States Laws and Regulations Affecting Archaeological Resources GEOGRAPHIC SETTING ................................................ 11 Forest Description and Environment PREHISTORIC OUTLINE ............................................... 17 Paleo Indian Stage Archaic Stage Poverty Point Period Woodland Stage Mississippian Stage HISTORICAL OUTLINE ................................................ 28 FOREST MANAGEMENT PRACTICES ............................. 35 Timber Practices Land Exchange Program Forest Engineering Program Special Uses Recreation KNOWN CULTURAL RESOURCES ON THE FOREST........... 41 Bienville National Forest Delta National Forest DeSoto National Forest ii KNOWN CULTURAL RESOURCES ON THE -

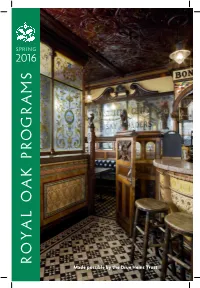

Ro Y Al O a K P R O Gr a Ms

SPRING 2016 ROYAL OAK PROGRAMS OAK ROYAL Made possible by the Drue Heinz Trust SPRING 2016 PROGRAM NEWS & INFORMATION Sincere Thanks to Our Sponsors for The Drue Heinz Lectures The Royal Oak Foundation’s national program of lectures is made possible by the continued generosity of the Drue Heinz Trust, our lead sponsor for the past 24 years. The committed support of the Drue Heinz Trust enables us to maintain a high quality of programming each season and for this we are deeply appreciative. For the Spring 2016 season we also gratefully acknowledge additional support for The Drue Heinz Lectures from the Marian Meaker Apteckar Foundation. Regional Corporate Support Thank you to FREEMAN’S for partnering and supporting our lectures in Philadelphia and Boston. Thanks to Arader Galleries for hosting our San Fran cisco lectures and receptions. Gratitude to Muller Incorporated in Philadelphia, and The House of Glunz in Chicago, for supporting our lectures on English Pubs and generously providing beer and wine at the events. Advance Registration, Seating, and Dress Code No tickets will be issued. You must register in advance for all programs. Registrations will not be held without payment or credit card—there are no tickets—and your name will be on our guest list at the door. There is a dress code at many of our lecture venues, some require formal business attire. Shorts, jeans, sneakers, and tee shirts are not acceptable in any weather. Incorrect attire may result in your being turned away at the door by the venue staff. Royal Oak is not responsible for venue dress code policies. -

Antislavery Violence and Secession, October 1859

ANTISLAVERY VIOLENCE AND SECESSION, OCTOBER 1859 – APRIL 1861 by DAVID JONATHAN WHITE GEORGE C. RABLE, COMMITTEE CHAIR LAWRENCE F. KOHL KARI FREDERICKSON HAROLD SELESKY DIANNE BRAGG A DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of The University of Alabama TUSCALOOSA, ALABAMA 2017 Copyright David Jonathan White 2017 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the collapse of southern Unionism between October 1859 and April 1861. This study argues that a series of events of violent antislavery and southern perceptions of northern support for them caused white southerners to rethink the value of the Union and their place in it. John Brown’s raid at Harpers Ferry, Virginia, and northern expressions of personal support for Brown brought the Union into question in white southern eyes. White southerners were shocked when Republican governors in northern states acted to protect members of John Brown’s organization from prosecution in Virginia. Southern states invested large sums of money in their militia forces, and explored laws to control potentially dangerous populations such as northern travelling salesmen, whites “tampering” with slaves, and free African-Americans. Many Republicans endorsed a book by Hinton Rowan Helper which southerners believed encouraged antislavery violence and a Senate committee investigated whether an antislavery conspiracy had existed before Harpers Ferry. In the summer of 1860, a series of unexplained fires in Texas exacerbated white southern fear. As the presidential election approached in 1860, white southerners hoped for northern voters to repudiate the Republicans. When northern voters did not, white southerners generally rejected the Union. -

Spring/Summer 2016 No

The Journal of Mississippi History Volume LXXVIII Spring/Summer 2016 No. 1 and No. 2 CONTENTS Introduction to Vintage Issue 1 By Dennis J. Mitchell Mississippi 1817: A Sociological and Economic 5 Analysis (1967) By W. B. Hamilton Protestantism in the Mississippi Territory (1967) 31 By Margaret DesChamps Moore The Narrative of John Hutchins (1958) 43 By John Q. Anderson Tockshish (1951) 69 By Dawson A. Phelps COVER IMAGE - Francis Shallus Map, “The State Of Mississippi and Alabama Territory,” courtesy of the Alabama Department of Archives and History. The original source is the Birmingham Public Library Cartography Collection. Recent Manuscript Accessions at Mississippi Colleges 79 University Libraries, 2014-15 Compiled by Jennifer Ford The Journal of Mississippi History (ISSN 0022-2771) is published quarterly by the Mississippi Department of Archives and History, 200 North St., Jackson, MS 39201, in cooperation with the Mississippi Historical Society as a benefit of Mississippi Historical Society membership. Annual memberships begin at $25. Back issues of the Journal sell for $7.50 and up through the Mississippi Museum Store; call 601-576-6921 to check availability. The Journal of Mississippi History is a juried journal. Each article is reviewed by a specialist scholar before publication. Periodicals paid at Jackson, Mississippi. Postmaster: Send address changes to the Mississippi Historical Society, P.O. Box 571, Jackson, MS 39205-0571. Email [email protected]. © 2018 Mississippi Historical Society, Jackson, Miss. The Department of Archives and History and the Mississippi Historical Society disclaim any responsibility for statements made by contributors. INTRODUCTION 1 Introduction By Dennis J. Mitchell Nearing my completion of A New History of Mississippi, I was asked to serve as editor of The Journal of Mississippi History (JMH). -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE GRETCHEN HAIEN 1171 Graymont Ave • Jackson, MS 39202 • (601) 291-8759 [email protected] EDUCATION: Bachelor of Arts, 1979 Belhaven University Jackson, Mississippi Master of Fine Arts 1982 Louisiana Tech University Ruston, Louisiana AWARDS: 2005 Mississippi Arts and Letters Award in Photography 2006 Interior Frontiers Portfolio Archived with The National Museum of Women in the Arts Library and Research Center 2007 Photography's Emerging Artist to Watch Award The National Museum of Women in the Arts 2011 Mississippi Invitational Exhibition, Mississippi Museum of Art 2012 Tenure Awarded: Associate Professor of Art Belhaven University 2015 Honored Artist Award: National Museum of Women in the Arts (NMWA), Mississippi Chapter (MSC) 2016 Incidentals book released: Annual Mississippi Book Festival 2017 Rank Promotion to Full Professor Belhaven University 2019 Judge's Favorite Award: MSC/NMWA Annua Artists' Showcase 2020 Judge's Favorite Award: MSC/NMWA Annua Artists' Showcase EXHIBITION HISTORY ONE PERSON: EJ. BELLOCQ GALLERY 1982 Louisiana Tech University EASTMAN KODAK GALLERY 1983 Rochester NY DEPARTMENT OF ARCHITECTURE GALLERY 1988 Mississippi State University —2— 121 MILLSAPS AVE GALLERY 1988 Jackson, MS LEWIS GALLERY 1990 Millsaps College THE GALLERY 1992 Jackson, MS THE PENNEBAKER GALLERY 2001 Jackson, MS BACKWOODS GALLERY 2002 St. Francisville, LA BESSIE CARY LEMLY GALLERY 2004 Belhaven College MS LIBRARYCOMMISSION: Dedication Exhibit 2006 Jackson, MS THE QUARTER GALLERY 2007 Jackson, MS One-To-One STUDIO GALLERY PREVIEW GALA 2008 Jackson, MS WALTER ANDERSON MUSEUM of ART 2008 Ocean Springs, MS M. SCHON GALLERY 2009 Natchez, MS BACKWOODS GALLERY 2015 St. Francisville, LA FISCHER GALLERY: Event Space 119 2016 Jackson, MS ACORN STUDIO GALLERY 2016 Clinton, MS JOHNSON HALL GALLERY 2017 Jackson Stale University —3— GALLERY ONE 2017 Jackson State University JOHN C. -

Story and Photos by Dennis Coello “The War Can Never Be Grant Took His Ultimately Successful but That Was in Late May 1863

PEDALING THE VICKSBURG CAMPAIGN Story and Photos by Dennis Coello “The war can never be Grant took his ultimately successful but That was in late May 1863. Upon hear- remarkably roundabout path. ing the news that Vicksburg was under brought to a close until that Thousands of men were put to work siege, Confederate President Davis met with key is in our pocket.” digging a canal through ground on the General Robert E. Lee, asking if he could Louisiana side of the Mississippi. If the spare some troops to aid Pemberton. Lee -President Lincoln, pointing to banks held against the rising river, Admiral replied that he couldn’t, that he was plan- Vicksburg, Mississippi, on the map Porter’s boats could pass out of range of ning an offensive north into Pennsylvania. Vicksburg’s guns. But the river rose so He argued that his movement, and his t had been an Easter Egg day in fast it nearly put Sherman’s troops into successes, would relieve the pressure of the saddle, with near constant April the trees. Another channel was attempted any additional Union armies being sent to tailwinds blowing me south across that would link swamps, bayous, a lake, Grant. ground that was river-flat and newly and two rivers before flowing back into Thousands would die on both sides dur- Igreen. For the first time since I’d pedaled the Mississippi 150 miles below Vicksburg. ing the 47-day siege of the fortress on the out of St. Louis a week earlier, I’d stayed This too failed, as did the blowing up of Mississippi. -

Two Centuries of Wheelchair Design, from Furniture to Film

Enwheeled: Two Centuries of Wheelchair Design, from Furniture to Film Penny Lynne Wolfson Submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree Master of Arts in the History of the Decorative Arts and Design MA Program in the History of the Decorative Arts and Design Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum, Smithsonian Institution and Parsons The New School for Design 2014 2 Fall 08 © 2014 Penny Lynne Wolfson All Rights Reserved 3 ENWHEELED: TWO CENTURIES OF WHEELCHAIR DESIGN, FROM FURNITURE TO FILM TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS i PREFACE ii INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1. Wheelchair and User in the Nineteenth Century 31 CHAPTER 2. Twentieth-Century Wheelchair History 48 CHAPTER 3. The Wheelchair in Early Film 69 CHAPTER 4. The Wheelchair in Mid-Century Films 84 CHAPTER 5. The Later Movies: Wheelchair as Self 102 CONCLUSION 130 BIBLIOGRAPHY 135 FILMOGRAPHY 142 APPENDIX 144 ILLUSTRATIONS 150 4 List of Illustrations 1. Rocking armchair adapted to a wheelchair. 1810-1830. Watervliet, NY 2. Pages from the New Haven Folding Chair Co. catalog, 1879 3. “Dimension/Weight Table, “Premier” Everest and Jennings catalog, April 1972 4. Screen shot, Lucky Star (1929), Janet Gaynor and Charles Farrell 5. Man in a Wheelchair, Leon Kossoff, 1959-62. Oil paint on wood 6. Wheelchairs in history: Sarcophagus, 6th century A.D., China; King Philip of Spain’s gout chair, 1595; Stephen Farffler’s hand-operated wheelchair, ca. 1655; and a Bath chair, England, 18th or 19th century 7. Wheeled invalid chair, 1825-40 8. Patent drawing for invalid locomotive chair, T.S. Minniss, 1853 9. -

Principal State and Territorial Officers

/ 2 PRINCIPAL STATE AND TERRITORIAL OFFICERS EXECUTIVE OFFICERS Atlorneys .... State Governors Lieulenanl Governors General . Secretaries of State. Alabama. James E. Foisoin J.C.Inzer .A. .A.. Carniichael Sibyl Pool Arizona Dan E. Garvey None Fred O. Wilson Wesley Boiin . Arkansas. Sid McMath Nathan Gordon Ike Marry . C. G. Hall California...... Earl Warren Goodwin J. Knight • Fred N. Howser Frank M. Jordan Colorado........ Lee Knous Walter W. Jolinson John W. Metzger George J. Baker Connecticut... Chester Bowles Wm. T. Carroll William L. Hadden Mrs. Winifred McDonald Delaware...:.. Elbert N. Carvel A. duPont Bayard .Mbert W. James Harris B. McDowell, Jr. Florida.. Fuller Warren None Richard W. Ervin R.A.Gray Georgia Herman Talmadge Marvin Griffin Eugene Cook Ben W. Fortson, Jr. * Idaho ;C. A. Robins D. S. Whitehead Robert E. Sniylie J.D.Price IlUnola. .-\dlai E. Stevenson Sher^vood Dixon Ivan.A. Elliott Edward J. Barrett Indiana Henry F. Schricker John A. Walkins J. Etnmett McManamon Charles F. Fleiiiing Iowa Wm. S.'Beardsley K.A.Evans Robert L. Larson Melvin D. Synhorst Kansas Frank Carlson Frank L. Hagainan Harold R. Fatzer (a) Larry Ryan Kentucky Earle C. Clements Lawrence Wetherby A. E. Funk • George Glenn Hatcher Louisiana Earl K. Long William J. Dodd Bolivar E. Kemp Wade O. Martin. Jr. Maine.. Frederick G. Pgynp None Ralph W. Farris Harold I. Goss Maryland...... Wm. Preston Lane, Jr. None Hall Hammond Vivian V. Simpson Massachusetts. Paul A. Dever C. F. Jeff Sullivan Francis E. Kelly Edward J. Croiiin Michigan G. Mennen Williams John W. Connolly Stephen J. Roth F. M. Alger, Jr.- Minnesota. -

Spring 2017 Playbook

STEM THE MCM PROGRAMS COMMUNITY PL AYBOOK PARTNERSHIPS SPRING 2017 • VOLUME 2 • ISSUE 1 BY THE NUMBERS encourage Mississippi children to develop stronger science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) skills. One of the most important roles that the museum can play as we delve into our mission is to foster CELEBRATE EVERY DAY! children’s natural curiosity--encouraging them to seek out those seemingly, never-ending questions. In the pages of this issue of the PlayBook, you will Each day at the Mississippi Children’s Museum (MCM) during 2017, we will see how we are fulfilling this purpose to develop more focus and access to be celebrating national days of recognition…. Do you know when the National experiences that encourage important 21st century skills. Day of Robotics is, or how about Apple Day? Do you know there is a National Day of Chess? We will learn new things, explore new concepts, Please join us at the museum to build, count, create, and make discoveries and celebrate the joys of everyday life both large and small. every day for both our youngest visitors and for the adults who love them. Speaking of questions, how do you think innovation and technology will Susan Garrard, Mississippi Children’s Museum President/CEO change our world in 2017? That is something we, at MCM, keep asking ourselves. As we try to anticipate the myriad of ways the world is changing, we have planned new programs and activities which will promote and CITY, STATE ZIP CODE ZIP STATE CITY, ADDRESS LINE 2 LINE ADDRESS ADDRESS LINE 1 LINE ADDRESS FIRST NAME LAST NAME LAST NAME FIRST JACKSON, MS 39296 MS JACKSON, Permit No. -

Narrating Jackson State: an Examination of Power Relations and Mississippi Newspaper Coverage of the 1970 Shootings at Jackson State College

University of Mississippi eGrove Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2014 Narrating Jackson State: An Examination Of Power Relations And Mississippi Newspaper Coverage Of The 1970 Shootings At Jackson State College Leslie Hassel University of Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd Part of the Journalism Studies Commons Recommended Citation Hassel, Leslie, "Narrating Jackson State: An Examination Of Power Relations And Mississippi Newspaper Coverage Of The 1970 Shootings At Jackson State College" (2014). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 872. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/etd/872 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NARRATING JACKSON STATE: AN EXAMINATION OF POWER RELATIONS AND MISSISSIPPI NEWSPAPER COVERAGE OF THE 1970 SHOOTINGS AT JACKSON STATE COLLEGE A Thesis presented in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Southern Studies at The University of Mississippi by LESLIE M. HASSEL April 2014 Copyright Leslie M. Hassel 2014 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT The following thesis examines media coverage of a 1970 campus shooting at Jackson State University in Jackson, Mississippi, during which two black students were killed and several others were injured. Over forty years after the shootings, the incident remains largely absent from the dominant historical narrative. This study posits that the contradictory accounts published by various Jackson-area news outlets blurred the lines between facts and subjective perspectives and as a consequence limited the resources used by historians to construct a narrative of the shootings. -

![Biographical Data of Members of Senate and House, Personnel of Standing Committees [1948] Mississippi](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5346/biographical-data-of-members-of-senate-and-house-personnel-of-standing-committees-1948-mississippi-1445346.webp)

Biographical Data of Members of Senate and House, Personnel of Standing Committees [1948] Mississippi

University of Mississippi eGrove Mississippi Legislature Hand Books State of Mississippi Government Documents 1948 Hand book : biographical data of members of Senate and House, personnel of standing committees [1948] Mississippi. Legislature Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/sta_leghb Part of the American Politics Commons Recommended Citation Mississippi. Legislature, "Hand book : biographical data of members of Senate and House, personnel of standing committees [1948]" (1948). Mississippi Legislature Hand Books. 6. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/sta_leghb/6 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the State of Mississippi Government Documents at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mississippi Legislature Hand Books by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. # I HAND BOOK. MISSISSIPPI LEGISLATURE 1948-1952 Regular Session 1948 BIOGRAPHICAL DATA OF MEMBERS OF SENATE AND HOUSE SENATE AND HOUSE COMMITTEES SENATE AND HOUSE RULES CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISIONS WALTER MURPHEY SECRETARY OF THE SENATE ROMAN KELLY CLERK OF THE H O USE Mississippi Legislature '' t M.C. 1948-1952 DIRECTORY JK 4630 . .A24 STATE OFFICIALS 1948-52 Governor ..............................•........... Fielding L. Wright Lieutenant Governor ................................ Sam Lumpkin Secretary of State.................................... Heber Ladner Attorney GeneraL .................................... Greek L. Rice State Treasurer.......................................