The Online Journal of Communication and Media Volume 3 Issue 4 October 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ro Y Al O a K P R O Gr a Ms

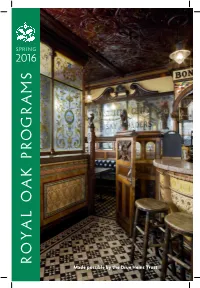

SPRING 2016 ROYAL OAK PROGRAMS OAK ROYAL Made possible by the Drue Heinz Trust SPRING 2016 PROGRAM NEWS & INFORMATION Sincere Thanks to Our Sponsors for The Drue Heinz Lectures The Royal Oak Foundation’s national program of lectures is made possible by the continued generosity of the Drue Heinz Trust, our lead sponsor for the past 24 years. The committed support of the Drue Heinz Trust enables us to maintain a high quality of programming each season and for this we are deeply appreciative. For the Spring 2016 season we also gratefully acknowledge additional support for The Drue Heinz Lectures from the Marian Meaker Apteckar Foundation. Regional Corporate Support Thank you to FREEMAN’S for partnering and supporting our lectures in Philadelphia and Boston. Thanks to Arader Galleries for hosting our San Fran cisco lectures and receptions. Gratitude to Muller Incorporated in Philadelphia, and The House of Glunz in Chicago, for supporting our lectures on English Pubs and generously providing beer and wine at the events. Advance Registration, Seating, and Dress Code No tickets will be issued. You must register in advance for all programs. Registrations will not be held without payment or credit card—there are no tickets—and your name will be on our guest list at the door. There is a dress code at many of our lecture venues, some require formal business attire. Shorts, jeans, sneakers, and tee shirts are not acceptable in any weather. Incorrect attire may result in your being turned away at the door by the venue staff. Royal Oak is not responsible for venue dress code policies. -

Children's Television in Asia : an Overview

This document is downloaded from DR‑NTU (https://dr.ntu.edu.sg) Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. Children's television in Asia : an overview Valbuena, Victor T 1991 Valbuena, V. T. (1991). Children's television in Asia : an overview. In AMIC ICC Seminar on Children and Television : Cipanas, September 11‑13, 1991. Singapore: Asian Mass Communiction Research & Information Centre. https://hdl.handle.net/10356/93067 Downloaded on 23 Sep 2021 22:26:31 SGT ATTENTION: The Singapore Copyright Act applies to the use of this document. Nanyang Technological University Library Children's Television In Asia : An Overview By Victor Valbuena CHILDREN'ATTENTION: ThSe S inTELEVISIONgapore Copyright Act apIpNlie s tASIAo the use: o f thiAs dNo cumOVERVIEent. NanyangW T echnological University Library Victor T. Valbuena, Ph.D. Senior Programme Specialist Asian Mass Communication Research and Information Centre Presented at the ICC - AMIC - ICWF Seminar on Children and Television Cipanas, West Java, Indonesia 11-13 September, 1991 CHILDREN'S TELEVISION IN ASIA: AN OVERVIEW Victor T. Valbuena The objective of this paper is to present an overview of children's AtelevisioTTENTION: The Snin gaiponre CAsiopyrigaht Aanct apdpl iessom to thee u seo off t histh doceu meproblemnt. Nanyang Tsec hnanologdic al issueUniversity sLib rary that beset it . By "children's television" is meant the range of programme materials made available specifically for children — from pure entertainment like televised popular games and musical shows to cartoon animation, comedies, news, cultural perform ances, documentaries, specially made children's dramas, science programmes, and educational enrichment programmes — and trans mitted during time slots designated for children. -

Two Centuries of Wheelchair Design, from Furniture to Film

Enwheeled: Two Centuries of Wheelchair Design, from Furniture to Film Penny Lynne Wolfson Submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree Master of Arts in the History of the Decorative Arts and Design MA Program in the History of the Decorative Arts and Design Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum, Smithsonian Institution and Parsons The New School for Design 2014 2 Fall 08 © 2014 Penny Lynne Wolfson All Rights Reserved 3 ENWHEELED: TWO CENTURIES OF WHEELCHAIR DESIGN, FROM FURNITURE TO FILM TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS i PREFACE ii INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1. Wheelchair and User in the Nineteenth Century 31 CHAPTER 2. Twentieth-Century Wheelchair History 48 CHAPTER 3. The Wheelchair in Early Film 69 CHAPTER 4. The Wheelchair in Mid-Century Films 84 CHAPTER 5. The Later Movies: Wheelchair as Self 102 CONCLUSION 130 BIBLIOGRAPHY 135 FILMOGRAPHY 142 APPENDIX 144 ILLUSTRATIONS 150 4 List of Illustrations 1. Rocking armchair adapted to a wheelchair. 1810-1830. Watervliet, NY 2. Pages from the New Haven Folding Chair Co. catalog, 1879 3. “Dimension/Weight Table, “Premier” Everest and Jennings catalog, April 1972 4. Screen shot, Lucky Star (1929), Janet Gaynor and Charles Farrell 5. Man in a Wheelchair, Leon Kossoff, 1959-62. Oil paint on wood 6. Wheelchairs in history: Sarcophagus, 6th century A.D., China; King Philip of Spain’s gout chair, 1595; Stephen Farffler’s hand-operated wheelchair, ca. 1655; and a Bath chair, England, 18th or 19th century 7. Wheeled invalid chair, 1825-40 8. Patent drawing for invalid locomotive chair, T.S. Minniss, 1853 9. -

Proceedings of the World Summit on Television for Children. Final Report.(2Nd, London, England, March 9-13, 1998)

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 433 083 PS 027 309 AUTHOR Clarke, Genevieve, Ed. TITLE Proceedings of the World Summit on Television for Children. Final Report.(2nd, London, England, March 9-13, 1998). INSTITUTION Children's Film and Television Foundation, Herts (England). PUB DATE 1998-00-00 NOTE 127p. AVAILABLE FROM Children's Film and Television Foundation, Elstree Studios, Borehamwood, Herts WD6 1JG, United Kingdom; Tel: 44(0)181-953-0844; e-mail: [email protected] PUB TYPE Collected Works - Proceedings (021) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC06 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Children; *Childrens Television; Computer Uses in Education; Foreign Countries; Mass Media Role; *Mass Media Use; *Programming (Broadcast); *Television; *Television Viewing ABSTRACT This report summarizes the presentations and events of the Second World Summit on Television for Children, to which over 180 speakers from 50 countries contributed, with additional delegates speaking in conference sessions and social events. The report includes the following sections:(1) production, including presentations on the child audience, family programs, the preschool audience, children's television role in human rights education, teen programs, and television by kids;(2) politics, including sessions on the v-chip in the United States, the political context for children's television, news, schools television, the use of research, boundaries of children's television, and minority-language television; (3) finance, focusing on children's television as a business;(4) new media, including presentations on computers, interactivity, the Internet, globalization, and multimedia bedrooms; and (5) the future, focusing on anticipation of events by the time of the next World Summit in 2001 and summarizing impressions from the current summit. -

Copyright and Use of This Thesis This Thesis Must Be Used in Accordance with the Provisions of the Copyright Act 1968

COPYRIGHT AND USE OF THIS THESIS This thesis must be used in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Reproduction of material protected by copyright may be an infringement of copyright and copyright owners may be entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. Section 51 (2) of the Copyright Act permits an authorized officer of a university library or archives to provide a copy (by communication or otherwise) of an unpublished thesis kept in the library or archives, to a person who satisfies the authorized officer that he or she requires the reproduction for the purposes of research or study. The Copyright Act grants the creator of a work a number of moral rights, specifically the right of attribution, the right against false attribution and the right of integrity. You may infringe the author’s moral rights if you: - fail to acknowledge the author of this thesis if you quote sections from the work - attribute this thesis to another author - subject this thesis to derogatory treatment which may prejudice the author’s reputation For further information contact the University’s Director of Copyright Services sydney.edu.au/copyright Structured Named Entities Nicky Ringland Supervisor: James Curran A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Information Technologies at The University of Sydney School of Information Technologies 2016 i Abstract The names of people, locations, and organisations play a central role in language, and named entity recognition (NER) has been widely studied, and successfully incorporated, into natural language processing (NLP) applications. -

PHILIPPINE PEN JOURNAL HEALING Herminio Beltran

Copyright ©2014 Philippine Center of International PEN, Inc. Copyright ©2014 of the individual articles remains with their respective authors Cover Image: Painting by Danny Sillada All rights reserved. No part of these pages, either text or image may be used for any purpose other than personal use. Reproduction, modification, storage in a retrieval system or retransmission, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical or otherwise, for reasons other than personal use, is strictly prohibited without prior written permission. This journal received a grant from PEN International and the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA) under the PEN 2014 Civil Society Programme. PHILIPPINE PEN JOURNAL HEALING Herminio Beltran, Jr. Editor Santiago B. Villafania Managing Editor Editorial Board Bienvenido Lumbera Susan Lara Philippine Center of International PEN F. Sionil José - Founder Board of Directors 2012-2014 Bienvenido Lumbera - National Chair Charlson Ong - Vice Chair Joselito Zulueta - National Secretary Board Members Herminio Beltran, Jr. Karina Bolasco José Wendell Capili Amadís Ma. Guerrero Glenn Sevilla Mas Elmer Ordoñez Victor Peñaranda Nicolas Pichay Jun Cruz Reyes Kristian Sendon Cordero Ricardo Suarez Soler Santiago B. Villafania Table of Contents Philippine PEN Founder’s Introduction ix by F. Sionil Jose Philippine PEN Journal Introduction xi The Healing PEN by H. S. Beltran, Jr. Prose A Time to Dance (Short Story) 1 by Anthony L. Tan The Island of the Living Dead (Chapter of a Novel) 13 by Cecilia Manguerra Brainard The Drifters of New River Pasig (Short Story) 23 by Ricardo Suarez Soler The Aroma of Horsemeat (Short Story) 43 by Mario Ignacio Miclat Baguio Earthquake: A Shaken City (Essay) 57 by Priscilla Supnet Macansantos The Strength of Roots or the Need for Flight? (Essay) 67 by Elizabeth Lolarga The Cancer Chronicles (Short Story) 85 by Maria Carmen A. -

Intellectual Property Center, 28 Upper Mckinley Rd. Mckinley Hill Town Center, Fort Bonifacio, Taguig City 1634, Philippines Tel

Intellectual Property Center, 28 Upper McKinley Rd. McKinley Hill Town Center, Fort Bonifacio, Taguig City 1634, Philippines Tel. No. 238-6300 Website: http://www.ipophil.gov.ph e-mail: [email protected] Publication Date: 07 August 2015 1 REGISTERED MARKS .......................................................................................................................................................... 2 1.1 REGISTERED NATIONAL MARKS .......................................................................................................................................... 2 *Registered Marks as of July 2015 Intellectual Property Center, 28 Upper McKinley Rd. McKinley Hill Town Center, Fort Bonifacio, Taguig City 1634, Philippines Tel. No. 238-6300 Website: http://www.ipophil.gov.ph e-mail: [email protected] Publication Date: 07 August 2015 1 REGISTERED MARKS 1.1 Registered national marks Registration / Registration No. Mark Applicant Nice class(es) Application No. Date 5 JIM-MAR ENTERPRISES, 1 4/2001/00004441 December McJIM 25 INC. [PH] 2004 25 2 4/2006/00012306 February ALLMYTEA MARVENTURE CORP. [PH] 32 2008 15 TOBY`S SPORTS QUORUM INTERNATIONAL 3 4/2007/00013135 November 41 ARENA & DEVICE INC. [PH] 2012 ISLAND AIR PRODUCTS 4 4/2008/00002756 7 July 2008 ISLAND 4 CORPORATION [PH] ISLAND AIR PRODUCTS 5 4/2008/00002758 7 July 2008 M GAS 4 CORPORATION [PH] 1; 2; 3; 4; 5; 7; 8; 9; 10; 12; 14; 16; 26 June PANASONIC CORPORATION 17; 19; 20; 21; 24; 6 4/2008/00007169 PANASONIC 2014 [JP] 27; 28; 35; 36; 38; 40; 41; 42; 43; 44 and45 BYD COMPANY LIMITED 7 4/2008/00012261 9 July 2009 BYD 12 [CN] BEAUMANOIR ASIA 7 May 8 4/2009/00001342 CACHE CACHE HOLDING SINGAPORE PTE. 18 and25 2015 LTD. [SG] 3; 9; 14; 16; 18; 5 August DISNEY ENTERPRISES, INC. -

The Proposition Production Notes

UK FILM COUNCIL presents a SUREFIRE production of an AUTONOMOUS and JACKIE O PRODUCTIONS Co-production in association with PICTURES IN PARADISE with the participation of THE PACIFIC FILM AND TELEVISION COMMISSION and THE FILM CONSORTIUM GUY PEARCE RAY WINSTONE DANNY HUSTON JOHN HURT DAVID WENHAM and EMILY WATSON THE PROPOSITION Written by NICK CAVE Directed by JOHN HILLCOAT Releases nationally October 6, 2005 Running Time: 104 mins Sound: Dolby SRD Aspect Ratio: 2.35:1 2 Index PRODUCTION INFORMATION PAGE 3 THE BILLING BLOCK PAGE 4 LOG LINE AND SHORT SYNOPSIS PAGE 5 LONG SYNOPSIS PAGE 6 DIRECTOR‘S STATEMENT PAGE 8 BACKGROUND TO THE FILM PAGE 10 THE CAST AND THEIR CHARACTERS PAGE 12 THE LOCATION PAGE 17 THE LOOK OF THE FILM PAGE 19 ABOUT THE CAST PAGE 20 ABOUT THE FILMMAKERS PAGE 27 APPENDIX 1: FULL LIST OF END CREDITS APPENDIX 2: THE BILLING BLOCK 3 Production Information THE PROPOSITION is a powerful and epic tale of two brothers in conflict. It has attracted a stellar international cast including Guy Pearce ( LA Confidential; Memento) ; Ray Winstone ( Sexy Beast; King Arthur; Ripley‘s Game) ; Danny Huston (Birth; Silver City) ; John Hurt ( Love and Death On Long Island; Hellboy); David Wenham ( The Lord of The Rings Trilogy; Van Helsing) and Emily Watson ( Life and Death of Peter Sellers; Punch Drunk Love; Breaking the Waves ). It was filmed on location in Winton, a remote northwestern outback town in Queensland, Australia. The original screenplay was written by music icon Nick Cave. It is directed by John Hillcoat ( Ghosts of the Civil Dead; To Have and to Hold) and produced by Chiara Menage ( Love Is the Devil) and Cat Villiers ( Saving Grace, No Man‘s Land), with Chris Brown ( Blurred; Under the Radar) and Jackie O‘Sullivan ( Witch Hunt). -

Fall/Winter 2020

The The The TheTheThe Journal Journal Journal JJoJoouuurrrnnnaaalll TheThe The ofof of JJooJuuorurnnranallal of of of ofof of MISSISSIPPIMISSISSIPPIMISSISSIPPI MISSISSIPPI MISSISSIPPI MISSISSIPPI MISSISSIPPIMISSISSIPPIMISSISSIPPI HHHISTORISTORISTORYYY uu u VolumeVolumeVolume LXXXII, LXXXII, LXXXII, Nº3 Nº3 and and Nº3 Nº4 Nº4 and Fall/Winter Nº4Fall/Winter Fall/Winter 2020 2020 2020 HHHISTORISTORISTORYYY uuu HISTORY HISTORY HISTORY VolumeVolumeVolume LXXXII, LXXXII, LXXXII, Nº3 Nº3 Nº3 and and and Nº4 Nº4 Nº4 Fall/Winter Fall/Winter Fall/Winter 2020 2020 2020 u u u VolumeVolume Volume LXXXII, LXXXII, LXXXII, Nº3 and Nº4 Fall/Winter 2020 Nº3 and Nº4 Fall/Winter 2020 Nº3 and Nº4 Fall/Winter 2020 Nº3 and Nº4 Fall/Winter MississippiMississippiMississippi Historical Historical Historical Society Society Society www.mississippihistory.orgwww.mississippihistory.orgwww.mississippihistory.org TITLE e Mississippi 1 Historical Society Founded November 9, 1858 EDITOR-IN-CHIEF 2020-2021 OFFICERS K B M D A H PRESIDENT Marshall Bennett, Jackson EDITOR D J. M VICE PRESIDENT P E, M S U-M Stephanie R. Rolph, Jackson EDITOR-IN-CHIEF EMERITUS SECRETARY–TREASURER E R. H William “Brother” Rogers, Brandon M H S IMMEDIATE PAST PRESIDENT MANAGING EDITOR Charles Westmoreland, Delta State University W “B” R M D A H EX-OFFICIO BIBLIOGRAPHICAL EDITOR Katie Blount, Jackson M V-A Columbus-Lowndes Public Library 2020-2021 BOARD OF DIRECTORS BOOK REVIEW EDITOR LA SHON F. BROOKS DIERDRE S. PAYNE C W Mississippi Valley State University Ridgeland Delta State University CARTER BURNS CHRISTIAN PINNEN Natchez Mississippi College BOARD OF PUBLICATIONS KELLY CANTRELL JAMES L. JIMMY ROBERTSON J F. B, J. W H M J East Mississippi Community College Jackson Natchez Clinton M C WILMA E. -

{PDF EPUB} Sleeping Beauty Memorial Photography in America by Stanley B

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Sleeping Beauty Memorial Photography in America by Stanley B. Burns Download Now! We have made it easy for you to find a PDF Ebooks without any digging. And by having access to our ebooks online or by storing it on your computer, you have convenient answers with Sleeping Beauty Iii Memorial Photography The Children . To get started finding Sleeping Beauty Iii Memorial Photography The Children , you are right to find our website which has a comprehensive collection of manuals listed. Our library is the biggest of these that have literally hundreds of thousands of different products represented. Finally I get this ebook, thanks for all these Sleeping Beauty Iii Memorial Photography The Children I can get now! cooool I am so happy xD. I did not think that this would work, my best friend showed me this website, and it does! I get my most wanted eBook. wtf this great ebook for free?! My friends are so mad that they do not know how I have all the high quality ebook which they do not! It's very easy to get quality ebooks ;) so many fake sites. this is the first one which worked! Many thanks. wtffff i do not understand this! Just select your click then download button, and complete an offer to start downloading the ebook. If there is a survey it only takes 5 minutes, try any survey which works for you. Sleeping Beauty: Memorial Photography in America by Stanley B. Burns. The Morbidly Fascinating Page. This Month's Subject: Images from Sleeping Beauty II. -

UNIVERSITY of the PHILIPPINES Bachelor of Arts in Communication

UNIVERSITY OF THE PHILIPPINES Bachelor of Arts in Communication Research Nicolle S. Timoteo Princess Rocel A. Uboñgen Seeing Children’s TV (SEECTV): The Values Presentation of the Children’s Shows of ABS-CBN2, GMA7 and TV5 Thesis Adviser: Professor Lourdes M. Portus, PhD College of Mass Communication University of the Philippines DIliman Date of Submission April 2012 Permission is given for the following people to have access to this thesis: Available to the general public Yes Available only after consultation with author/thesis adviser No Available only to those bound by confidentiality agreement No Student‘s signature: Student‘s signature: Signature of thesis adviser: UNIVERSITY PERMISSION We hereby grant the University of the Philippines non-exclusive worldwide, royalty-free license to reproduce, publish and publicly distribute copies of this thesis or dissertation in whatever form subject to the provisions of applicable laws, the provisions of the UP IPR policy and any contractual obligations, as well as more specific permission marking on the Title Page. Specifically we grant the following rights to the University: a) to upload a copy of the work in these database of the college/school/institute/department and in any other databases available on the public internet; b) to publish the work in the college/school/institute/department journal, both in print and electronic or digital format and online; and c) to give open access to above-mentioned work, thus allowing ―fair use‖ of the work in accordance with the provisions of the Intellectual Property Code of the Philippines (Republic Act No. 8293), especially for teaching, scholarly and research purposes. -

Court to Resolve Senate Case Today

nmvAil library ananas QVarietyj Micronesia’s Leading Newspaper Since 1972 Vol. 21 . No. 121 „ ' ■' Saipan, MP 9695Ö ©1992 Marianas Variety Friday ■ September 4,* 1992 Serving CNMI for 20 Years C ourt to resolve Senate case today By Gaynor L. Dumat-ol presiding judge. nity might not apply in this case. “It is our position that the ses He said immunity applies only to THE SUPERIOR Court yester sion is in violation of the court possible slander charges arising day reaffirmed its declaration that order,” Bellas told reporters after from statements made during a Joseph S. Inos was still the the hearing. legislative session or hearing. president of the Senate, despite a Atalig is expected to finally A person found guilty of session called by six senators decide during the continuation of criminal contempt may be im inos Demapan Wednesday afternoon which “re the hearing this afternoon who prisoned for a maximum of six elected” Juan S. Demapan to the between Inos and Demapan is months and/or fined $100. Pierce asked Atalig to declare as merely two-thirds of the mem hotly contested seat legally entitled to occupy the At the Senate yesterday, “moot” Inos’ motion against bership. “The court order still remains,” Senate presidency. Demapan called another session Demapan. .Seven senators originally Presiding Judge Pedro Atalig said If Demapan loses, he and the attended by the same six senators Atalig said he would “solve” signed the memorandum calling during yesterday )s hearing where five other senators who joined who re-elected him Wednesday. today whether the issue raised by fa· Wednesday’s session but Juan only counsels of the two «con the session and voted for him last They passed several resolu Inos has become moot (with the S.