Tougaloo During the Presidency of Dr. Adam Daniel Beittel (1960-1964)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History: Black Lawyers in Louisiana Prior to 1950

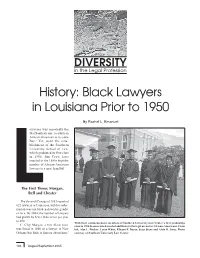

DIVERSITY in the Legal Profession History: Black Lawyers in Louisiana Prior to 1950 By Rachel L. Emanuel ouisiana was reportedly the first Southern state to admit an African-American to its state Bar.1 Yet, until the esta- blishment of the Southern University School of Law, which graduated its first class in 1950, Jim Crow laws enacted in the 1880s kept the number of African-American lawyers to a mere handful. The First Three: Morgan, LBell and Chester The Seventh Census of 1853 reported 622 lawyers in Louisiana, but this infor- mation was not broken down by gender or race. By 1864, the number of lawyers had grown by fewer than seven per year to 698. With their commencement, members of Southern University Law Center’s first graduating C. Clay Morgan, a free black man, class in 1950 became much-needed additions to the legal arena for African-Americans. From was listed in 1860 as a lawyer in New left, Alex L. Pitcher, Leroy White, Ellyson F. Dyson, Jesse Stone and Alvin B. Jones. Photo Orleans but little is known about him.2 courtesy of Southern University Law Center. 104 August/September 2005 There were only four states reported to have admitted black lawyers to the bar prior to that time, none of them in the South. The states included Indiana (1860s), Maine (1844), Massachusetts (1845), New York (1848) and Ohio (1854). If, as is believed, Morgan was Louisiana’s first black lawyer,3 he would have been admitted to the Bar almost 10 years earlier than the average date for the other Southern states (Arkansas, 1866; Tennessee, 1868; Florida and Missis- sippi, 1869; Alabama, Georgia, Ken- tucky, South Carolina and Virginia, 1871; and Texas, 1873). -

Dillard University, Which Has Its Roots in Reconstruction, Has Outlasted Segregation, Discrimination and Hurricane Katrina

NEW ORLEANS From Bienville to Bourbon Street to bounce. 300 moments that make New Orleans unique. WHAT HAPPENED Dillard 1718 ~ 2018 University was chartered on 300 June 6, 1930. TRICENTENNIAL THE HISTORIC NEW ORLEANS COLLECTION PHOTOS THE NEW ORLEANS ADVOCATE A group portrait of graduating nurses in front of Flint-Goodrich Hospital of Dillard University in 1932 Straight University in 1908, on Canal and Tonti streets Class President Nicole Tinson takes a selfie with then frst lady Michelle Obama during Dillard’s 2014 graduation. Dillard President Walter M.Kimbrough stands behind Obama. THE HISTORIC NEW ORLEANS COLLECTION New Orleans University in 1908, on St. Charles Avenue, was razed to make way for De La Salle High School. Dillard University, which has its roots in Reconstruction, has outlasted segregation, discrimination and Hurricane Katrina. THE NEW ORLEANS ADVOCATE The university was created in 1930 from the opposition of the neighborhood. The first two historically black colleges — Straight president of the university, Will W. Alexander, University and Union Normal School — later was a white man because there were concerns named New Orleans University. that a white faculty wouldn’t want to answer The two schools were both created in 1868 to a black president. When Dillard opened its to educate newly freed African-Americans. new campus in 1935, it featured prominent fac- The schools offered professional training, in- ulty including Horace Mann Bond in psychol- The library of the new cluding in law, medicine and nursing. New ogy and education; Frederick Douglass Hall in Dillard University in 1935 Orleans University opened the Flint-Go- music; Lawrence D. -

Have a Seat to Be Heard: the Sit-In Movement of the 1960S

(South Bend, IN), Sept. 2, 1971. Have A Seat To Be Heard: Rodgers, Ibram H. The Black Campus Movement: Black Students The Sit-in Movement Of The 1960s and the Racial Reconstih,tion ofHigher Education, 1965- 1972. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012. "The Second Great Migration." In Motion AAME. Accessed April 9, E1~Ai£-& 2017. http://www.inmotion.org/print. Sulak, Nancy J. "Student Input Depends on the Issue: Wolfson." The Preface (South Bend, IN), Oct. 28, 1971. "If you're white, you're all right; if you're black, stay back," this derogatory saying in an example of what the platform in which seg- Taylor, Orlando. Interdepartmental Communication to the Faculty regation thrived upon.' In the 1960s, all across America there was Council.Sept.9,1968. a movement in which civil rights demonstrations were spurred on by unrest that stemmed from the kind of injustice represented by United States Census Bureau."A Look at the 1940 Census." that saying. Occurrences in the 1960s such as the Civil Rights Move- United States Census Bureau. Last modified 2012. ment displayed a particular kind of umest that was centered around https://www.census.gov/newsroom/cspan/194ocensus/ the matter of equality, especially in regards to African Americans. CSP AN_194oslides. pdf. More specifically, the Sit-in Movement was a division of the Civil Rights Movement. This movement, known as the Sit-in Movement, United States Census Bureau. "Indiana County-Level Census was highly influenced by the characteristics of the Civil Rights Move- Counts, 1900-2010." STATSINDIANA: Indiana's Public ment. Think of the Civil Rights Movement as a tree, the Sit-in Move- Data Utility, nd. -

Colby Alumnus Vol. 52, No. 3: Spring 1963

Colby College Digital Commons @ Colby Colby Alumnus Colby College Archives 1963 Colby Alumnus Vol. 52, No. 3: Spring 1963 Colby College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/alumnus Part of the Higher Education Commons Recommended Citation Colby College, "Colby Alumnus Vol. 52, No. 3: Spring 1963" (1963). Colby Alumnus. 216. https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/alumnus/216 This Other is brought to you for free and open access by the Colby College Archives at Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Alumnus by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Colby. - 00 . Colby Alumnus srR1Nc 1963 rl!llll Ma;ne � Literary I and ¥ Theological I Infiitution I . �1m11m11as011a� REMARK BY PRE IDE! T TRIDER IN CLOSI c THE CHARTER ESQ ICE 'TEN 'JAL OB ERVA 'CE ON FEBR RY 13. History is not merely a linear continuum Of events. It is a succession of happenings inex tricably interwoven with others in time past and time future, a dynamic process in which eons come and go, and in which individuals and institutions from time to time emerge in such a way as to affect for the bet ter history's course, some in heroic fashion, others in modest but enduring ways. Such men were the great names in Colby's past, and such an institution is Through its first century and a half this college Colby. has not only endured but prospered. It has main tained through these years sound ideals and objec ti es. It has earned the friendship of its community and its state, has enjoyed rewarding relationships with other fine institutions of education, near and far, and now, in its one-hundred-fiftieth year, can be said to have achieved a stature that commands national re spect. -

Movement 1954-1968

CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT 1954-1968 Tuesday, November 27, 12 NEW MEXICO OFFICE OF AFRICAN AMERICAN AFFAIRS Curated by Ben Hazard Tuesday, November 27, 12 Montgomery Bus Boycott and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, The initial phase of the black protest activity in the post-Brown period began on December 1, 1955. Rosa Parks of Montgomery, Alabama, refused to give up her seat to a white bus rider, thereby defying a southern custom that required blacks to give seats toward the front of buses to whites. When she was jailed, a black community boycott of the city's buses began. The boycott lasted more than a year, demonstrating the unity and determination of black residents and inspiring blacks elsewhere. Martin Luther King, Jr., who emerged as the boycott movement's most effective leader, possessed unique conciliatory and oratorical skills. He understood the larger significance of the boycott and quickly realized that the nonviolent tactics used by the Indian nationalist Mahatma Gandhi could be used by southern blacks. "I had come to see early that the Christian doctrine of love operating through the Gandhian method of nonviolence was one of the most potent weapons available to the Negro in his struggle for freedom," he explained. Although Parks and King were members of the NAACP, the Montgomery movement led to the creation in 1957 of a new regional organization, the clergy-led Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) with King as its president. King remained the major spokesperson for black aspirations, but, as in Montgomery, little-known individuals initiated most subsequent black movements. On February 1, 1960, four freshmen at North Carolina Agricultural and Technical College began a wave of student sit-ins designed to end segregation at southern lunch counters. -

MIXED MARTIAL ARTS BOUT RESULTS (Boxing, Kickboxing, Grappling, Etc) * Information Circled in Red Is Required

"not for use with other combat sports MIXED MARTIAL ARTS BOUT RESULTS (boxing, kickboxing, grappling, etc) * Information circled in red is required California State Athletic Commission CITY : Commerce DATE: 05 31 2013 2005 Evergreen Street Sacramento CA 95815 STATE/PROVINCE : C VENUE : Commerce Casino P: 916 263 2195 F: 916 263 2197 [email protected] EVENT NAME : BAMMA PROMOTER : Brett Roberts EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR: Andy Foster JUDGE(s): 1. Abe Belardo 2. Wade Viera Mike Bray SUPPORTING OFFICIALS: 4. Marcos Rosale Brandon Saucedo NAME TITLE REFEREE(s): . John Mccarthy 2. Mike Beltran Mark Lawley NAME: TITLE: NAME TITLE RINGSIDE DOCTOR(s): Diego Allende 2. Pat Golden 3. Mitch Jelen NAME: TITLE ANNOUNCER: NAME TITLE TIMEKEEPER: Veronica Montes and Chris Raymmond NAME: TITLE MATCHMAKER: BOUT # RDS. STATUS FIGHTER NAME MMA ID#....DOB |WEIGHT |WINNER |RD. TIME METHOD SUSPENSIONS 119-569 Unanimous Decision Keith- 180/180 poss frac L-th Pro Clyde Keith 165.1 MM DD YYYY Judge# 3 3 5:00 Score 26 30 1 Judge# Am 143-073 core 26 - 30 Carrington Banks 156 Judge# Score 25 - 30 leree # 121-597 Unanimous Decision Matthews-60/60- cut to L cheek Pro AJ Matthews 184 MM DD YYYY Judges 3 5:00 4 Score 26 - 30 2 3 Score 26 - 30 Am 128-857 Judges 5 Ben Reiter 185.5 Judge# Score 26 - 30 MM DD YYYY 125-592 TKO, ref stopped due to strikes Pro Javy Ayala 266 MM DD YYYY Judge# 1 Score 3 1 3:02 3 Judge# core Am 23-870 Broughton- 45/30 Roy Broughton 264.3 Judge# 4 core MM DD YYYY Referee # 145-557 TKO, ref stopped due to strikes Pro ermaine McDermott 205.8 Judge# Score 3 1 0:20 4 Judge# core 142-439 Watkins- 45/30 and 180/180 R-knee Blake Watkins 205.1 Judge# Score Referee # BOUT # RDS. -

Teaching Anne Moody *Coming of Age in Mississippi* Discussion/Aug 1997

H-Women Teaching Anne Moody *Coming of Age in Mississippi* Discussion/Aug 1997 Page published by Kolt Ewing on Thursday, June 12, 2014 Teaching Anne Moody *Coming of Age in Mississippi* Discussion/Aug 1997 Query From Seth Wigderson [email protected] 02 Aug 1997 I am going to be using Anne Moody's Coming of Age In Mississippi in a US history survey course and I was wondering if anyone 1. could pass on experiences in using the book in class 2. can tell what happened to her after the book Thanks. X-POSTS FROM H-SOUTH AND RESPONSES FROM H-WOMEN Editor's Note: Thanks to Seth for putting together all these messages. Some have been posted already on H-Women, some have not. In any case, I found it fascinating to read them all at once. Good idea! Steve Reschly *** From: Seth Wigderson [email protected] 11 Aug 1997 A while ago I posted a query to H-Women and H-Teach asking for experience in using Anne Moody's *Coming of Age in Mississippi" as well as information on her later life. I got a wonderful series of replies from those lists, and as H-South which also picked up the query as well as some private posts. My students were very positive about the book which I used in conjunction with "Anchor of my Soul," a documentary about Portland Maine's black community's 175 year existence. I found Pam Pennock's writing suggestion (ask them to write briefly on two moving passages) very effective. -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE GRETCHEN HAIEN 1171 Graymont Ave • Jackson, MS 39202 • (601) 291-8759 [email protected] EDUCATION: Bachelor of Arts, 1979 Belhaven University Jackson, Mississippi Master of Fine Arts 1982 Louisiana Tech University Ruston, Louisiana AWARDS: 2005 Mississippi Arts and Letters Award in Photography 2006 Interior Frontiers Portfolio Archived with The National Museum of Women in the Arts Library and Research Center 2007 Photography's Emerging Artist to Watch Award The National Museum of Women in the Arts 2011 Mississippi Invitational Exhibition, Mississippi Museum of Art 2012 Tenure Awarded: Associate Professor of Art Belhaven University 2015 Honored Artist Award: National Museum of Women in the Arts (NMWA), Mississippi Chapter (MSC) 2016 Incidentals book released: Annual Mississippi Book Festival 2017 Rank Promotion to Full Professor Belhaven University 2019 Judge's Favorite Award: MSC/NMWA Annua Artists' Showcase 2020 Judge's Favorite Award: MSC/NMWA Annua Artists' Showcase EXHIBITION HISTORY ONE PERSON: EJ. BELLOCQ GALLERY 1982 Louisiana Tech University EASTMAN KODAK GALLERY 1983 Rochester NY DEPARTMENT OF ARCHITECTURE GALLERY 1988 Mississippi State University —2— 121 MILLSAPS AVE GALLERY 1988 Jackson, MS LEWIS GALLERY 1990 Millsaps College THE GALLERY 1992 Jackson, MS THE PENNEBAKER GALLERY 2001 Jackson, MS BACKWOODS GALLERY 2002 St. Francisville, LA BESSIE CARY LEMLY GALLERY 2004 Belhaven College MS LIBRARYCOMMISSION: Dedication Exhibit 2006 Jackson, MS THE QUARTER GALLERY 2007 Jackson, MS One-To-One STUDIO GALLERY PREVIEW GALA 2008 Jackson, MS WALTER ANDERSON MUSEUM of ART 2008 Ocean Springs, MS M. SCHON GALLERY 2009 Natchez, MS BACKWOODS GALLERY 2015 St. Francisville, LA FISCHER GALLERY: Event Space 119 2016 Jackson, MS ACORN STUDIO GALLERY 2016 Clinton, MS JOHNSON HALL GALLERY 2017 Jackson Stale University —3— GALLERY ONE 2017 Jackson State University JOHN C. -

The Jackson Sit-In by Anne Moody from Coming of Age in Mississippi I

The Jackson Sit-In By Anne Moody From Coming of Age in Mississippi I had become very friendly with my social science professor, John Salter, who was in charge of NAACP activities on campus. All during the year, while the NAACP conducted a boycott of the downtown stores in Jackson, I had been one of Salter's most faithful canvassers and church speakers. During the last week of school, he told me that sit-in demonstrations were about to start in Jackson and that he wanted me to be the spokesman for a team that would sit-in at Woolworth's lunch counter. The two other demonstrators would be classmates of mine, Memphis and Pearlena. Pearlena was a dedicated NAACP worker, but Memphis had not been very involved in the Movement on campus. It seemed that the organization had had a rough time finding students who were in a position to go to jail. I had nothing to lose one way or the other. Around ten o’clock the morning of the demonstrations, NAACP headquarters alerted the news services. As a result, the police department was also informed, but neither the policemen nor the newsmen knew exactly where or when the demonstrations would start. They stationed themselves along Capitol Street and waited. To divert attention from the sit-in at Woolworth's, the picketing started at J.C. Penney's a good fifteen minutes before. The pickets were allowed to walk up and down in front of the store three or four times before they were arrested. At exactly 11 A.M., Pearlena, Memphis, and I entered Woolworth's from the rear entrance. -

The Complex Relationship Between Jews and African Americans in the Context of the Civil Rights Movement

The Gettysburg Historical Journal Volume 20 Article 8 May 2021 The Complex Relationship between Jews and African Americans in the Context of the Civil Rights Movement Hannah Labovitz Gettysburg College Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/ghj Part of the History Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Recommended Citation Labovitz, Hannah (2021) "The Complex Relationship between Jews and African Americans in the Context of the Civil Rights Movement," The Gettysburg Historical Journal: Vol. 20 , Article 8. Available at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/ghj/vol20/iss1/8 This open access article is brought to you by The Cupola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The Cupola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Complex Relationship between Jews and African Americans in the Context of the Civil Rights Movement Abstract The Civil Rights Movement occurred throughout a substantial portion of the twentieth century, dedicated to fighting for equal rights for African Americans through various forms of activism. The movement had a profound impact on a number of different communities in the United States and around the world as demonstrated by the continued international attention marked by recent iterations of the Black Lives Matter and ‘Never Again’ movements. One community that had a complex reaction to the movement, played a major role within it, and was impacted by it was the American Jewish community. The African American community and the Jewish community were bonded by a similar exclusion from mainstream American society and a historic empathetic connection that would carry on into the mid-20th century; however, beginning in the late 1960s, the partnership between the groups eventually faced challenges and began to dissolve, only to resurface again in the twenty-first century. -

A Study of Title Iii, Higher Education Act of 1965, and an Evaluation of Its Impact at Selected Predominantly Black Colleges

A STUDY OF TITLE III, HIGHER EDUCATION ACT OF 1965, AND AN EVALUATION OF ITS IMPACT AT SELECTED PREDOMINANTLY BLACK COLLEGES APPROVED: Graduate Committee: Dean of the]Graduate" School Gupta, Bhagwan S., A Study of Title III, Higher Educa- tion Act of 1965, and. an Evaluation of Xts Impact at Selected Predominantly Black Colleges. Doctor of Philosophy (Higher Education), December, 1971, 136 pp., 4 tables, bibliography, 66 titles. In the past half-century, comprehensive studies have been made by individuals and agencies to determine the future role of black institutions in American higher education. Early studies concerning black higher education suggested ways to improve and strengthen the black colleges; however, it was not until the year 1964 that major legislation, in the form of the Civil Rights Act, was passed. The purpose of this study was to describe the passage of the Higher Education Act of 1965, and to evaluate faculty development programs at selected black institutions in light of the objectives and guidelines established for the use of Title III funds. To carry out the purpose of this study, six questions were formulated. These questions dealt with (1) the eligibility requirements for colleges and univer- sities, (2) the Title III programs related to faculty development, (3) criteria to be used by institutions for selection of faculty members, (4) enhancing the chances for black institutions to compete with predominantly white institutions, (5) the effects of the programs in terms of short-term gains versus long-term gains, and (6) the insti- tutions ' ability or inability to take full advantage of opportunities provided under Title III. -

Spring 2017 Playbook

STEM THE MCM PROGRAMS COMMUNITY PL AYBOOK PARTNERSHIPS SPRING 2017 • VOLUME 2 • ISSUE 1 BY THE NUMBERS encourage Mississippi children to develop stronger science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) skills. One of the most important roles that the museum can play as we delve into our mission is to foster CELEBRATE EVERY DAY! children’s natural curiosity--encouraging them to seek out those seemingly, never-ending questions. In the pages of this issue of the PlayBook, you will Each day at the Mississippi Children’s Museum (MCM) during 2017, we will see how we are fulfilling this purpose to develop more focus and access to be celebrating national days of recognition…. Do you know when the National experiences that encourage important 21st century skills. Day of Robotics is, or how about Apple Day? Do you know there is a National Day of Chess? We will learn new things, explore new concepts, Please join us at the museum to build, count, create, and make discoveries and celebrate the joys of everyday life both large and small. every day for both our youngest visitors and for the adults who love them. Speaking of questions, how do you think innovation and technology will Susan Garrard, Mississippi Children’s Museum President/CEO change our world in 2017? That is something we, at MCM, keep asking ourselves. As we try to anticipate the myriad of ways the world is changing, we have planned new programs and activities which will promote and CITY, STATE ZIP CODE ZIP STATE CITY, ADDRESS LINE 2 LINE ADDRESS ADDRESS LINE 1 LINE ADDRESS FIRST NAME LAST NAME LAST NAME FIRST JACKSON, MS 39296 MS JACKSON, Permit No.