Targums, the New Testament, and Biblical Theology of the Messiah Michael B

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wisdom in Daniel and the Origin of Apocalyptic

WISDOM IN DANIEL AND THE ORIGIN OF APOCALYPTIC by GERALD H. WILSON University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia 30602 In this paper, I am concerned with the relationship of the book of Daniel and the biblical wisdom literature. The study draws its impetus from the belief of von Rad that apocalyptic is the "child" of wisdom (1965, II, pp. 304-15). My intent is to test von Rad's claim by a study of wisdom terminology in Daniel in order to determine whether, in fact, that book has its roots in the wisdom tradition. Adequate evidence has been gathered to demonstrate a robust connection between the nar ratives of Daniel 1-6 and mantic wisdom which employs the interpreta tion of dreams, signs and visions (Millier, 1972; Collins, 1975). Here I am concerned to dispell the continuing notion that apocalyptic as ex hibited in Daniel (especially in chapters 7-12) is the product of the same wisdom circles from which came the proverbial biblical books of Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, Job and the later Ben Sirach. 1 I am indebted to the work of Why bray ( 1974), who has dealt exhaustively with the terminology of biblical wisdom, and to the work of Crenshaw (1969), who, among others, has rightly cautioned that the presence of wisdom vocabulary is insufficient evidence of sapiential influence. 2 Whybray (1974, pp. 71-154) distinguishes four categories of wisdom terminology: a) words from the root J:ikm itself; b) other characteristic terms occurring only in the wisdom corpus (5 words); c) words char acteristic of wisdom, but occurring so frequently in other contexts as to render their usefulness in determining sapiential influence questionable (23 words); and d) words characteristic of wisdom, but occurring only occasionally in other OT traditions (10 words). -

The Reception of the Book of Daniel (And

The Reception of the Book of Daniel (and Danielic Literature) in the Early Church Wisdom and Apocalypticism Section SBL Annual Meeting in Washington, November 18-22, 2006 by Gerbern S. Oegema, McGill University 3520 University Street, Montreal, QC. Canada H3A 2A7 all rights reserved: for seminar use only. Any quotation from or reference to this paper should be made only with permission of author: [email protected] Abstract Whereas cosmogony has traditionally been seen as a topic dealt with primarily in wisdom literature, and eschatology, a field mostly focused upon in apocalyptic literature, the categorization of apocryphal and pseudepigraphic writings into sapiential, apocalyptic, and other genres has always been considered unsatisfactory. The reason is that most of the Pseudepigrapha share many elements of various genres and do not fit into only one genre. The Book of Daniel, counted among the Writings of the Hebrew Bible and among the Prophets in the Septuagint as well as in the Christian Old Testament, is such an example. Does it deal with an aspect of Israel’s origin and history, a topic dealt mostly dealt with in sapiential thinking, or only with its future, a question foremost asked with an eschatological or apocalyptic point of view? The answer is that the author sees part of the secrets of Israel’s future already revealed in its past. It is, therefore, in the process of investigating Israel’s history that apocalyptic eschatology and wisdom theology meet. This aspect is then stressed even more in the later reception history of the Book of Daniel as well as of writings ascribed to Daniel: if one wants to know something about Israel’s future in an ever-changing present situation, one needs to interpret the signs of the past. -

Introduction

Please provide footnote text Chapter 1 Introduction In the sixteenth and the first half of the seventeenth century Christian printers in Europe published Targum texts and provided them with Latin translations. Four complete polyglot Bibles were produced in this period (1517–1657), each containing more Targumic material than the previous one. Several others were planned or even started, but most plans were hampered by lack of money. And in between, every decade one or more Biblical books in Aramaic and Latin saw the light. This is remarkable, since the Targums were Jewish translations of the Hebrew Bible into Aramaic and scarcely functioned in the Jewish liturgy anymore.1 Jews used them primarily as a means to teach Aramaic in the Jewish educational system.2 Yet, Christian scholars were, as parts of the new human- ist atmosphere, interested in ancient texts and their interpretations. And the Targums were interpretations of the Hebrew Bible, the ultimate source of the Christian Old Testament. Moreover, they were written in Aramaic, a language so close to Hebrew that their Jewish translators must have understood the original text more thoroughly than any scholar brought up in another tongue. In contrast, many scholars of those days objected to the study of Jewish lit- erature, including the Targums. A definition of Targum is ‘a translation that combines a highly literal rendering of the original text with material added into the translation in a seamless manner’.3 Moreover, ‘poetic passages are often expanded rather than translated.’4 Christian scholars were interested in the ‘highly literal rendering’, but often rejected the added and expanded ma- terial. -

The Body and Voice of God in the Hebrew Bible

Johanna Stiebert The Body and Voice of God in the Hebrew Bible ABSTRACT This article explores the role of the voice of God in the Hebrew Bible and in early Jew- ish interpretations such as the Targumim. In contrast to the question as to whether God has a body, which is enmeshed in theological debates concerning anthropomor- phism and idolatry, the notion that God has a voice is less controversial but evidences some diachronic development. KEYWORDS body of God, voice of God, Torah, Targumim, Talmud, anthropomorphic BIOGRAPHY Johanna Stiebert is a German New Zealander and Associate Professor of Hebrew Bible at the University of Leeds. Her primary research interests with regard to the Hebrew Bible are centred particularly on self-conscious emotions, family structures, gender and sexuality. In Judaism and Christianity, which both hold the Hebrew Bible canonical, the question as to whether God has a body is more sensitive and more contested than the question as to whether God has a voice.1 The theological consensus now tends to be that God is incorporeal, and yet the most straightforward interpretation of numerous Hebrew Bible passages is that God is conceived of in bodily, anthropomorphic terms – though often there also exist attendant possibilities of ambiguity and ambivalence. The famil- iar divine statement “let us make humankind in our image, according to our likeness” (betsalmēnû kidmûtēnû; Gen. 1:26), for example, seems to envisage – particularly in 1 A version of this paper was presented at “I Sing the Body Electric”, an interdisciplinary day confer- ence held at the University of Hull, UK, on 3 June 2014 to explore body and voice from musicological, technological, and religious studies perspectives. -

The Use of the Expressions 'Prophetic Spirit' and 'Holy Spirit' in the Targum

Aramaic Studies Aramaic Studies 11 (2013) 167–186 brill.com/arst The Use of the Expressions ‘Prophetic Spirit’ and ‘Holy Spirit’ in the Targum and the Dating of the Targums Pere Casanellas University of Barcelona, Spain Abstract Among different expressions used by the targums to translate the Hebrew word meaning ‘spirit’,the terms ‘prophetic spirit’ and ‘Holy Spirit’ stand out. I will try to demonstrate (contra P. Schäfer, ‘Die Termini “Heiliger Geist” und “Geist der Prophetie” in den Targumim und das Verhältnis der Targumim zueinander’, VT 20 (1970), pp. 304–314) that both terms often have that both can have a similar relationship to ,( חור a basis in the Hebrew text (namely, the word prophecy and that the expression ‘Holy Spirit’ is as old as ‘prophetic spirit’ or even older. I will also outline the semantic contexts that underlie the use of one or other expression, which has nothing to do with the antiquity of either term. Keywords spirit of prophecy; Holy Spirit; Targum Jonathan; Targum Onqelos; Targum Neofiti; Frag- mentary Targum; Targum Pseudo-Jonathan; Palestinian targums; dating of the targums 1. Introduction ,in the Hebrew Bible is associated with God, that is to say ַהוּר When the word when the spirit comes from God, the targums often add a qualifier to this word, usually a positive one, although not always (for example, in Tg 1Kgs. 22.21–23 according to the targumist the lying spirit placed in the mouth of the prophets of King Ahab comes ‘from before the lord’). The main qualifiers of this kind .of might, mighty’ (Tg Jdg. -

The Old Testament: Part Thirteen Wisdom Books of the Bible

The Old Testament: Part Thirteen Wisdom Books of the Bible The following are some excerpts from a fuller experience and reason. The means of acquiring introduction to the Wisdom books of the bible. (For wisdom are through study, instruction, discipline, the complete introduction, see Article 66 on my reflection, meditation and counsel. He who hates Commentaries on the Books of the Old Testament.) wisdom is called a fool, sinner, ignorant, proud, wicked, and senseless. The message of the Wisdom There are five books in the Old Testament called teachers can be summed up in the words of St. Paul: “Wisdom books”: Job, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, “What things are true, whatever honorable, whatever Ecclesiasticus and Wisdom. In Catholic Bibles, the just, whatever holy, whatever lovable, whatever of Song of Songs and Psalms are also grouped in the good repute, if there be any virtue, if anything worthy Wisdom books section. of praise, think upon these things. And what you have The reader who moves from the historical or learned and received and heard and seen in me, these prophetical books of the Bible into the Wisdom books things practice (Phil.4:8-9); whether you eat or drink, will find him/herself in a different world. While the or do anything else, do all for the glory of God” (1Cor. Wisdom books differ among themselves in both style 10:31). and subject matter, they have in common the following characteristics: The Catholic Bible – Personal Study Edition offers the following short description for each of the seven books 1. They show minimum interest in the great themes contained in the Wisdom section of Catholic Bibles. -

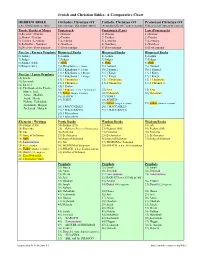

Hebrew and Christian Bibles: a Comparative Chart

Jewish and Christian Bibles: A Comparative Chart HEBREW BIBLE Orthodox Christian OT Catholic Christian OT Protestant Christian OT (a.k.a. TaNaK/Tanakh or Mikra) (based on longer LXX; various editions) (Alexandrian LXX, with 7 deutero-can. bks) (Cath. order, but 7 Apocrypha removed) Torah / Books of Moses Pentateuch Pentateuch (Law) Law (Pentateuch) 1) Bereshit / Genesis 1) Genesis 1) Genesis 1) Genesis 2) Shemot / Exodus 2) Exodus 2) Exodus 2) Exodus 3) VaYikra / Leviticus 3) Leviticus 3) Leviticus 3) Leviticus 4) BaMidbar / Numbers 4) Numbers 4) Numbers 4) Numbers 5) Devarim / Deuteronomy 5) Deuteronomy 5) Deuteronomy 5) Deuteronomy Nevi’im / Former Prophets Historical Books Historical Books Historical Books 6) Joshua 6) Joshua 6) Joshua 6) Joshua 7) Judges 7) Judges 7) Judges 7) Judges 8) Samuel (1&2) 8) Ruth 8) Ruth 8) Ruth 9) Kings (1&2) 9) 1 Kingdoms (= 1 Sam) 9) 1 Samuel 9) 1 Samuel 10) 2 Kingdoms (= 2 Sam) 10) 2 Samuel 10) 2 Samuel 11) 3 Kingdoms (= 1 Kings) 11) 1 Kings 11) 1 Kings Nevi’im / Latter Prophets 12) 4 Kingdoms (= 2 Kings) 12) 2 Kings 12) 2 Kings 10) Isaiah 13) 1 Chronicles 13) 1 Chronicles 13) 1 Chronicles 11) Jeremiah 14) 2 Chronicles 14) 2 Chronicles 14) 2 Chronicles 12) Ezekiel 15) 1 Esdras 13) The Book of the Twelve: 16) 2 Esdras (= Ezra + Nehemiah) 15) Ezra 15) Ezra Hosea, Joel, 17) Esther (longer version) 16) Nehemiah 16) Nehemiah Amos, Obadiah, 18) JUDITH 17) TOBIT Jonah, Micah, 19) TOBIT 18) JUDITH Nahum, Habakkuk, 19) Esther (longer version) 17) Esther (shorter version) Zephaniah, Haggai, 20) 1 MACCABEES 20) -

A Thematic Study of Doctrines on Death and Afterlife According to Targum Qohelet

A Thematic Study of Doctrines on Death and Afterlife according to Targum Qohelet By LAWRENCE RONALD LINCOLN DISSERTATION Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PHD in Ancient Cultures FACULTY OF ARTS AND SOCIAL SCIENCES PROMOTER: PROF JOHANN COOK April 2019 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Declaration By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. April 2019 Copyright © 2019 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved ii Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Abstract This dissertation examined how the Targum radically transformed Qohelet’s pessimistic, secular and cynical views on the human condition by introducing a composite rabbinical theology throughout the translation with the purpose of refuting the futility of human existence and the finality of death. The Targum overturned the personal observations of Qohelet and in its place proposed a practical guide for the living according to the principles of rabbinic theological principles. While BibQoh provided few if any solutions for the many pitfalls and challenges of life and lacking any clear references to an eschatology, the Targum on the other hand promoted the promise of everlasting life as a model for a beatific eschatological future. The dissertation demonstrated how the targumist exploited a specific translation strategy to introduce rabbinic ideologies to present the targum as an alternative context to the ideologies of wisdom literature as presented in Biblical Qohelet. -

Be Read, but Not Translated (M

CHAPTER FIFTEEN לא מתרגם בציבורא—NOT TO BE TRANSLATED IN PUBLIC Introduction The subject of “forbidden targumim” has been discussed periodically in papers devoted to the specific topic, as well as in more general studies of the relationship between the targumim and other rabbinic literature.1 The point of departure of these studies has understandably been the lists contained in the Tannaitic sources and the discussion of those lists in the Babylonian and Palestinian Talmuds. Much effort has been expended in trying to establish a “correct version” of the lists, in identifying the passages in question, and in search of a rationale for each of the particular forbidden items. As readily observed, there is almost complete unanimity among the rabbinic lists regarding the passages in the Pentateuch that “may The Mishnah .נקראין ואינן מתרגמין ”,be read, but not translated (m. Megillah 4:10), Tosefta (t. Megillah 4:35 ff ), and the later Talmudic sources2 all agree that the “Story of Reuben” (Gen 35:22) and the “sec- ond account of the [golden] calf” (Exod 32:21–35) fall into this cat- egory. The only other Pentateuchal passage assigned to this group is “the priestly blessing” (Num 6:24–26), according to the Babylonian and Palestinian Talmuds (b. Megillah 25b; y. Megillah 75c). But this seems to be based upon a compounded error. J. Heinemann has argued rather convincingly that the statement regarding the “priestly blessing” was not originally related to the weekly Torah reading or its rendition 1 E.g., A. Geiger, Urschrift und Übersetzungen der Bibel (Breslau, 1857), pp. -

THE PENTATEUCHAL TARGUMS: a REDACTION HISTORY and GENESIS 1: 26-27 in the EXEGETICAL CONTEXT of FORMATIVE JUDAISM by GUDRUN EL

THE PENTATEUCHAL TARGUMS: A REDACTION HISTORY AND GENESIS 1: 26-27 IN THE EXEGETICAL CONTEXT OF FORMATIVE JUDAISM by GUDRUN ELISABETH LIER THESIS Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR LITTERARUM ET PHILOSOPHIAE in SEMITIC LANGUAGES AND CULTURES in the FACULTY OF HUMANITIES at the UNIVERSITY OF JOHANNESBURG PROMOTER: PROF. J.F. JANSE VAN RENSBURG APRIL 2008 ABSTRACT THE PENTATEUCHAL TARGUMS: A REDACTION HISTORY AND GENESIS 1: 26-27 IN THE EXEGETICAL CONTEXT OF FORMATIVE JUDAISM This thesis combines Targum studies with Judaic studies. First, secondary sources were examined and independent research was done to ascertain the historical process that took place in the compilation of extant Pentateuchal Targums (Fragment Targum [Recension P, MS Paris 110], Neofiti 1, Onqelos and Pseudo-Jonathan). Second, a framework for evaluating Jewish exegetical practices within the age of formative Judaism was established with the scrutiny of midrashic texts on Genesis 1: 26-27. Third, individual targumic renderings of Genesis 1: 26-27 were compared with the Hebrew Masoretic text and each other and then juxtaposed with midrashic literature dating from the age of formative Judaism. Last, the outcome of the second and third step was correlated with findings regarding the historical process that took place in the compilation of the Targums, as established in step one. The findings of the summative stage were also juxtaposed with the linguistic characterizations of the Comprehensive Aramaic Lexicon Project (CAL) of Michael Sokoloff and his colleagues. The thesis can report the following findings: (1) Within the age of formative Judaism pharisaic sages and priest sages assimilated into a new group of Jewish leadership known as ‘rabbis’. -

The Book of Esther Cambridge University Press Ware House

'!'HE CAMBRIDGE BIBLE FOR SCHOOLS AND COLLEGES GENERAL EDITOR FOR THE OLD TESTAMENT: A. F. KIRKPATRICK, D.D. DEAN OF ELY THE BOOK OF ESTHER CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS WARE HOUSE, c. F. CLAY, MANAGER. U.onl:lon: FETTER LANE, E.C. 4illasgabJ: 50, WELLINGTON STREET. l.eip)ig: F. A BROCKHAUS, j4cb; liort.: G. P. PUTNAM'S SONS. Jilomua~ anb Qt:alcutta: MACMILLAN AND CO., Lw. [All Rights reserwd] THE BOOK OF ESTHER With Introduction and Notes by THE REY. A. w. STREANE, D.D. Fellow of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge CAMBRIDGE: at the University Press r907 Qt11mbtibgt: PRINTED BY JOHN CLAY, M.A. AT THE UNIVERSITY PRESS. PREFACE BY THE GENERAL EDITOR FOR THE OLD TESTAMENT. THE present General Editor for the Old Testament in the Cambridge Bible for Schools and Colleges desires to say that, in accordance with the policy of his predecessor the Bishop of Worcester, he does not hold himself responsible for the particular interpreta tions adopted or for the opinions expressed by the editors of the several Books, nor has he endeavoured to bring them into agreement with one another. It is inevitable that there should be differences of opinion in regard to many questions of criticism and interpretation, and it seems best that these differences should find free expression in different volumes. He has endeavoured to secure, as far as possible, that the general scope and character of the series should be observed, and that views which have ·a reasonable claim to consideration should not be ignored, but he has felt it best that the final responsibility should, in general, rest with the individual contributors. -

THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY of AMERICA Targum Song of Songs

THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF AMERICA Targum Song of Songs: Language and Lexicon A DISSERTATION Submitted to the Faculty of the Department of Semitic and Egyptian Languages and Literatures School of Arts and Sciences Of The Catholic University of America In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree Doctor of Philosophy © Copyright All Rights Reserved By Andrew W. Litke Washington, D.C. 2016 Targum Song of Songs: Language and Lexicon Andrew W. Litke, Ph.D. Director: Edward M. Cook, Ph.D. Targum Song of Songs (TgSong) contains linguistic features from “literary” Aramaic as found in Targum Onqelos and Targum Jonathan, western Aramaic, eastern Aramaic, Biblical Aramaic, and Syriac. A similar mixing of linguistic features is evident in other targumim, and their language is collectively termed Late Jewish Literary Aramaic (LJLA). Though several of these LJLA texts have been linguistically analyzed, one text that has not received such an analysis is TgSong. Since TgSong expands well beyond the underlying Hebrew, it provides an excellent example from which to analyze distinct linguistic features. This dissertation approaches TgSong in two ways. First, it is a descriptive grammar and includes standard grammatical categories: phonology and orthography, morphology, syntax, and lexical stock. Second, in order to determine how the language is mixed and where the language of TgSong fits into the spectrum of Aramaic dialects, each grammatical feature and lexical item is compared to the other pre-modern Aramaic dialects. This dissertation shows first, that the mixing of linguistic features in TgSong is not haphazard. Individual linguistic features are largely consistent in the text, regardless of their dialectal classification.