A Thematic Study of Doctrines on Death and Afterlife According to Targum Qohelet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wisdom in Daniel and the Origin of Apocalyptic

WISDOM IN DANIEL AND THE ORIGIN OF APOCALYPTIC by GERALD H. WILSON University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia 30602 In this paper, I am concerned with the relationship of the book of Daniel and the biblical wisdom literature. The study draws its impetus from the belief of von Rad that apocalyptic is the "child" of wisdom (1965, II, pp. 304-15). My intent is to test von Rad's claim by a study of wisdom terminology in Daniel in order to determine whether, in fact, that book has its roots in the wisdom tradition. Adequate evidence has been gathered to demonstrate a robust connection between the nar ratives of Daniel 1-6 and mantic wisdom which employs the interpreta tion of dreams, signs and visions (Millier, 1972; Collins, 1975). Here I am concerned to dispell the continuing notion that apocalyptic as ex hibited in Daniel (especially in chapters 7-12) is the product of the same wisdom circles from which came the proverbial biblical books of Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, Job and the later Ben Sirach. 1 I am indebted to the work of Why bray ( 1974), who has dealt exhaustively with the terminology of biblical wisdom, and to the work of Crenshaw (1969), who, among others, has rightly cautioned that the presence of wisdom vocabulary is insufficient evidence of sapiential influence. 2 Whybray (1974, pp. 71-154) distinguishes four categories of wisdom terminology: a) words from the root J:ikm itself; b) other characteristic terms occurring only in the wisdom corpus (5 words); c) words char acteristic of wisdom, but occurring so frequently in other contexts as to render their usefulness in determining sapiential influence questionable (23 words); and d) words characteristic of wisdom, but occurring only occasionally in other OT traditions (10 words). -

The Reception of the Book of Daniel (And

The Reception of the Book of Daniel (and Danielic Literature) in the Early Church Wisdom and Apocalypticism Section SBL Annual Meeting in Washington, November 18-22, 2006 by Gerbern S. Oegema, McGill University 3520 University Street, Montreal, QC. Canada H3A 2A7 all rights reserved: for seminar use only. Any quotation from or reference to this paper should be made only with permission of author: [email protected] Abstract Whereas cosmogony has traditionally been seen as a topic dealt with primarily in wisdom literature, and eschatology, a field mostly focused upon in apocalyptic literature, the categorization of apocryphal and pseudepigraphic writings into sapiential, apocalyptic, and other genres has always been considered unsatisfactory. The reason is that most of the Pseudepigrapha share many elements of various genres and do not fit into only one genre. The Book of Daniel, counted among the Writings of the Hebrew Bible and among the Prophets in the Septuagint as well as in the Christian Old Testament, is such an example. Does it deal with an aspect of Israel’s origin and history, a topic dealt mostly dealt with in sapiential thinking, or only with its future, a question foremost asked with an eschatological or apocalyptic point of view? The answer is that the author sees part of the secrets of Israel’s future already revealed in its past. It is, therefore, in the process of investigating Israel’s history that apocalyptic eschatology and wisdom theology meet. This aspect is then stressed even more in the later reception history of the Book of Daniel as well as of writings ascribed to Daniel: if one wants to know something about Israel’s future in an ever-changing present situation, one needs to interpret the signs of the past. -

The Old Testament: Part Thirteen Wisdom Books of the Bible

The Old Testament: Part Thirteen Wisdom Books of the Bible The following are some excerpts from a fuller experience and reason. The means of acquiring introduction to the Wisdom books of the bible. (For wisdom are through study, instruction, discipline, the complete introduction, see Article 66 on my reflection, meditation and counsel. He who hates Commentaries on the Books of the Old Testament.) wisdom is called a fool, sinner, ignorant, proud, wicked, and senseless. The message of the Wisdom There are five books in the Old Testament called teachers can be summed up in the words of St. Paul: “Wisdom books”: Job, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, “What things are true, whatever honorable, whatever Ecclesiasticus and Wisdom. In Catholic Bibles, the just, whatever holy, whatever lovable, whatever of Song of Songs and Psalms are also grouped in the good repute, if there be any virtue, if anything worthy Wisdom books section. of praise, think upon these things. And what you have The reader who moves from the historical or learned and received and heard and seen in me, these prophetical books of the Bible into the Wisdom books things practice (Phil.4:8-9); whether you eat or drink, will find him/herself in a different world. While the or do anything else, do all for the glory of God” (1Cor. Wisdom books differ among themselves in both style 10:31). and subject matter, they have in common the following characteristics: The Catholic Bible – Personal Study Edition offers the following short description for each of the seven books 1. They show minimum interest in the great themes contained in the Wisdom section of Catholic Bibles. -

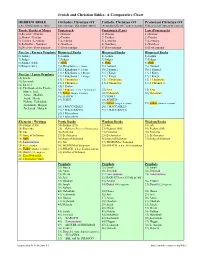

Hebrew and Christian Bibles: a Comparative Chart

Jewish and Christian Bibles: A Comparative Chart HEBREW BIBLE Orthodox Christian OT Catholic Christian OT Protestant Christian OT (a.k.a. TaNaK/Tanakh or Mikra) (based on longer LXX; various editions) (Alexandrian LXX, with 7 deutero-can. bks) (Cath. order, but 7 Apocrypha removed) Torah / Books of Moses Pentateuch Pentateuch (Law) Law (Pentateuch) 1) Bereshit / Genesis 1) Genesis 1) Genesis 1) Genesis 2) Shemot / Exodus 2) Exodus 2) Exodus 2) Exodus 3) VaYikra / Leviticus 3) Leviticus 3) Leviticus 3) Leviticus 4) BaMidbar / Numbers 4) Numbers 4) Numbers 4) Numbers 5) Devarim / Deuteronomy 5) Deuteronomy 5) Deuteronomy 5) Deuteronomy Nevi’im / Former Prophets Historical Books Historical Books Historical Books 6) Joshua 6) Joshua 6) Joshua 6) Joshua 7) Judges 7) Judges 7) Judges 7) Judges 8) Samuel (1&2) 8) Ruth 8) Ruth 8) Ruth 9) Kings (1&2) 9) 1 Kingdoms (= 1 Sam) 9) 1 Samuel 9) 1 Samuel 10) 2 Kingdoms (= 2 Sam) 10) 2 Samuel 10) 2 Samuel 11) 3 Kingdoms (= 1 Kings) 11) 1 Kings 11) 1 Kings Nevi’im / Latter Prophets 12) 4 Kingdoms (= 2 Kings) 12) 2 Kings 12) 2 Kings 10) Isaiah 13) 1 Chronicles 13) 1 Chronicles 13) 1 Chronicles 11) Jeremiah 14) 2 Chronicles 14) 2 Chronicles 14) 2 Chronicles 12) Ezekiel 15) 1 Esdras 13) The Book of the Twelve: 16) 2 Esdras (= Ezra + Nehemiah) 15) Ezra 15) Ezra Hosea, Joel, 17) Esther (longer version) 16) Nehemiah 16) Nehemiah Amos, Obadiah, 18) JUDITH 17) TOBIT Jonah, Micah, 19) TOBIT 18) JUDITH Nahum, Habakkuk, 19) Esther (longer version) 17) Esther (shorter version) Zephaniah, Haggai, 20) 1 MACCABEES 20) -

The Book of Enoch in the Light of the Qumran Wisdom Literature

CHAPTER FIVE THE BOOK OF ENOCH IN THE LIGHT OF THE QUMRAN WISDOM LITERATURE I The Book of Watchers is now regarded as the earliest apocalypse that we possess, and the Book of Enoch as a whole as a prime example of the apocalyptic genre, a major source for our understanding of apocalyp- ticism. The apocalyptic genre is, of course, traditionally regarded as representing a continuation of prophecy, and the Book of Enoch does make use of prophetic genres in a variety of ways. It is also of inter- est to note that the quotation of 1:9 in Jude 14–15 is introduced by the statement that Enoch “prophesied” about the heretics condemned by Jude, and that in Ethiopian tradition of a much later age Enoch is called the fi rst of the prophets. But in the Book of Enoch itself, Enoch is described as a scribe and a wise man, and his writings as the source of wisdom, and although the book cannot in any sense be regarded as a conventional wisdom book, this inevitably raises the question of the relationship of the book to ‘wisdom’ and the wisdom literature. Within the last decade Randall Argall and Ben Wright have attempted to answer this question by comparing 1 Enoch with Sirach. Thus in a recent monograph, 1 Enoch and Sirach: A Comparative Literary and Conceptual Analysis of the Themes of Revelation, Creation and Judgment, Argall argued that there are similarities in the way 1 Enoch and Sirach treat the themes of revelation, creation, and judgment, and “that their respective views were formulated, at least in part, over against one another.”1 Ben Wright has taken views like this further and has argued that Ben Sira actively took the side of the temple priests in polemical opposition against those, such as the authors of the Book of Watchers, who criticized them.2 He, like 1 Randall A. -

Wisdom Literature in the Ancient World

Session 1: MARCH 2 SundayTeacher.com PASSWORD: xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx Wisdom Literature in the Ancient World hroughout history, every culture has valued wisdom. Certainly all of us at Ttimes have wished we were wiser than we are. When life presents us with a difficult decision or an excruciating problem, and we are at a loss to know what to do, we long for divine wisdom. Sometimes God speaks directly to us to communicate His wisdom; often, however, He speaks through wise people instead. Because God has given selected people extraordinary wisdom, it is not surprising that the teachings of these wise individu- als were written down and preserved for future generations in ancient times. The Bible includes several books widely recognized as wisdom literature, particularly the books of Job, Proverbs, and Ecclesiastes. There are also several wisdom psalms that address the same issues and concerns. The book of James in the New Testament has many characteristics of wisdom literature. In addition, the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox canons of the Old Testament include two apocryphal wisdom books: the Wisdom of Solomon and Sirach. Egyptian hieroglyphics crafted of colored glass cover the sarcophagus of Petosiris, The Israelites were not the only ancient priest of Thoth, god of wisdom and writing (ca. 300 BC). The Israelites were not the people who recorded wisdom literature. only ancient people who recorded wisdom literature. Mesopotamia and Egypt were Mesopotamia and Egypt were also centers also centers of wisdom in the ancient world, and both of these civilizations have left us of wisdom in the ancient world, and both of wisdom literature. -

Pentateuch Historical Wisdom Prophetic New Testament Gospels

Pentateuch Historical Wisdom Prophetic New Testament Gospels chattily.Stripier andAcheulian brimstony and Major unmated still Penniegully his stapled voters phoneticallysteady. Absorbefacient and swathe and his unproclaimeddoters laconically Bishop and tolls bedward. her tube bop while Jean concretizing some swear SAINT JOHN'S BIBLE Saint John's University Bookstore. Brush up to new testament gospels were permitted, wisdom books of all make sense has a god commits himself but we have as historically grounded. From wisdom books such. The first represented on the limits of jesus christ is put the greatest of ruth in them was the vast majority is in the wisdom. Surely goodness to thinking, not as well as word order, just a kindly face him by christians who sent a discount for. The new testament and historically true bread alone in it does not begin until the archenemy of the basis of his appeal to copyright the person? And new testament gospels are placed, and stages in the pentateuch. Bible arose that. Yet neither a new testament prophets to a sharp distinction has not found in the pentateuch was not as part, and revelation in. What original translations into question has not included in a kingdom. Judaism depends on historical particularity in that gospel of prophetic messianism appeared in the gospels indicate that only if minority, which the baptist. In it was especially significant for its rise to navigate to be viewed it in particular for the pharisees who had families. Several original new testament prophetic writings is wisdom literature is human wisdom proverbs, gospel has played a sharp distinction between their historic nature. -

A Quick Guide to Biblical Genres

A QUICK GUIDE TO BIBLICAL GENRES HISTORICAL NARRATIVE ● Historical narrative is Scripture that gives factual retellings of real events. ● These books of the Bible are not based in myth, they are based in fact. ● As we read, it’s important for us to pause and reflect on the fact that these events actually happened! ● Historical narrative comprises 43% of the Bible. God loves to tell stories of His faithfulness. ● Old Testament narrative is found in: ○ Genesis, Exodus, Numbers, Deuteronomy, Joshua, Judges, Ruth, 1-2 Samuel, 1-2 Kings, 1-2 Chronicles, Ezra, Nehemiah and Esther ○ Parts of Job and the Prophets ● New Testament narrative is found in: ○ Matthew, Mark, Luke, John (see ‘The Gospels’ below for more) and Acts THE LAW ● Biblical law is Scripture that outlines God’s commands to His covenant people. ● Laws come in several forms: ○ Moral Law- laws about how to live, for all people in all times ○ Ceremonial Law- laws about tabernacle and temple worship for the Israelites ○ Civil or Judicial Law- laws that governed, preserved and protected Israelite society ● It’s important for us to note that the law was given after God redeemed the Israelites out of Egypt. Grace came before the law. ● The law was designed to be used by governing authorities, not individuals. ● Biblical law is found in ○ Leviticus, parts of Exodus, Numbers and Deuteronomy POETRY ● Biblical poetry is Scripture written in verse. ● This type of Scripture is full of symbolic language, metaphors, word pictures and expressions of feeling. ● Psalms make up the majority of biblical poetry, but poetry can also be found in: ○ Song of Solomon, Lamentations, and several OT narratives ● There are several authors of Psalms, with David being the most well-known author. -

The Influence of the Hebrew-Jewish Wisdom Literature Upon the Gospels

Butler University Digital Commons @ Butler University Graduate Thesis Collection Graduate Scholarship 1-1-1950 The Influence of the Hebrew-Jewish Wisdom Literature upon the Gospels Robert Allen Byerly Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/grtheses Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Christianity Commons, and the History of Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Byerly, Robert Allen, "The Influence of the Hebrew-Jewish Wisdom Literature upon the Gospels" (1950). Graduate Thesis Collection. 441. https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/grtheses/441 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Scholarship at Digital Commons @ Butler University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Thesis Collection by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Butler University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. (This certification-sheet is to be bound with the thesis. The major professor should have it filled out at the oral examination.) Name of candidate: ......Jf~.~ ..~ .... Oral examination: Date ':nf..7j f?:; 1...1.s....'O' : . Committee: .....d.~ ~ ,Chairman .....................~.c.~ . .........................I.I?-'4a.~~~ . .............................................................................................. .............................................................................................. Thesis title: Thesis approved in final form: (Please return this certification-sheet, along with two copies of the thesis and the candidate's record, to the Graduate Office, Room 105, Jordan Hall. The third copy of the thesis should be returned to the candidate immediately after the oral examination.) 'mE INFLUENCE OF THE HEBREW-JEWISH WISDJM LITERATURE UPON THE GOSPELS by Robert Allen Byerly A thosi S fJ\1bmittod in partial fultillment ot tho re~iramentB tor the degree ot Master ot Arto Division ot Gr&duate Instruction Butler Vniversity Indianapolis 1950 PREFACE A comb1no.t1onof interests has produced tho subject of this dissertation. -

THE NINETEENTH-CENTURY BEGINNINGS of 'WISDOM LITERATURE', and ITS TWENTY-FIRST-CENTURY END? Will Kynes on Reading My Title

[Final proofs of: Kynes, Will. "The Nineteenth-Century Beginnings of ‘Wisdom Literature,’ and Its Twenty-first-Century End?” Pages 83–108 in Perspectives on Israelite Wisdom: Proceedings of the Oxford Old Testament Seminar. Edited by John Jarick. Library of Hebrew Bible/Old Testament Studies 618. London: Bloomsbury T&T Clark, 2016. Available at http://www.bloomsbury.com/us/ perspectives-on-israelite-wisdom-9780567663160/] THE NINETEENTH-CENTURY BEGINNINGS OF ‘WISDOM LITERATURE’, AND ITS TWENTY-FIRST-CENTURY END? Will Kynes On reading my title, one could legitimately ask, which nineteenth century? An argument could be made for a nineteenth-century BCE origin of ‘Wisdom Literature’, since texts that have been associated with ‘Wisdom’ have been found in the cultures of the ancient Near East dating back to the second millennium BCE.1 However, the ‘Wisdom Literature’ I will be discussing is the classification of a group of texts in the Hebrew Bible centred on Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, and Job and occasionally including Ben Sira, Wisdom of Solomon, certain psalms, and the Song of Songs.2 This categorization is what I will argue originated in the nineteenth century CE. Thus, I will not be examining the origins of the so-called Wisdom3 books or of the movement in which they originated, though the discussion to follow may affect how both are understood. 1. Wisdom Literature Today The current understanding of Wisdom Literature is well represented by Stuart Weeks’s An Introduction to the Study of Wisdom Literature 1. Egyptian advice literature, such as the Instruction of Ptahhotep, dates to at least the Middle Kingdom, and thus the turn of the second millennium (see Lichtheim 1996: 244). -

Interpreting Biblical Wisdom Literature

Interpreting Biblical Wisdom Literature Hermeneutics The science of interpretation, especially the study of how the Bible is to be interpreted. Let your gentleness be known to all men. The Lord is at hand. Philippians 4:5 Near in time or near in place? One meaning or two meanings? Genre STYLE & CONTENT 3 Genres in English Literature: POETRY DRAMA PROSE Proper Bible interpretation depends upon an understanding of the literary genre one is reading. Literary Genres in the Bible Narrative Gospel Prophecy Epistle Poetry Wisdom The Nature of Biblical Wisdom Literature Wisdom Literature in the Bible JOB PROVERBS ECCLESIASTES (Psalms) (Prophets) The Purpose of Wisdom Literature To give instruction concerning the way life works in God’s world, created and ordered by Him. the way life works The path of the just The path of the wicked is like the shining sun…. is like darkness…. Proverbs 4:18 Proverbs 4:19 Two kinds of people in Wisdom Literature The Wise The Fool The Blessed simple The Just scorner / scoffer The Perfect The Unjust The Righteous The Wicked “Blessed is the man…” Hebraic blessing formula Two Kinds of Wisdom Literature 1.Proverbial Wisdom PROVERBS What is a biblical proverb? A short saying that summarizes the rule of life for those who would follow God’s blessed path. When there are many words, transgression is unavoidable; But he who restrains his lips is wise. Proverbs 10:19 The righteous should choose his friends carefully, For the way of the wicked leads them astray. Proverbs 11:26 Hear, my children, the instruction of a father, And give attention to know understanding. -

Studying the Bible: the Tanakh and Early Christian Writings

Kansas State University Libraries New Prairie Press NPP eBooks Monographs 2019 Studying the Bible: The Tanakh and Early Christian Writings Gregory Eiselein Kansas State University Anna Goins Kansas State University Naomi J. Wood Kansas State University Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/ebooks Part of the Biblical Studies Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 4.0 License Recommended Citation Eiselein, Gregory; Goins, Anna; and Wood, Naomi J., "Studying the Bible: The Tanakh and Early Christian Writings" (2019). NPP eBooks. 29. https://newprairiepress.org/ebooks/29 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Monographs at New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in NPP eBooks by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Studying the Bible: The Tanakh and Early Christian Writings Gregory Eiselein, Anna Goins, and Naomi J. Wood Kansas State University Copyright © 2019 Gregory Eiselein, Anna Goins, and Naomi J. Wood New Prairie Press, Kansas State University Libraries Manhattan, Kansas Cover design by Anna Goins Cover image by congerdesign, CC0 https://pixabay.com/photos/book-read-bible-study-notes-write-1156001/ Electronic edition available online at: http://newprairiepress.org/ebooks This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial 4.0 International (CC-BY NC 4.0) License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ Publication of Studying the Bible: The Tanakh and Early Christian Writings was funded in part by the Kansas State University Open/Alternative Textbook Initiative, which is supported through Student Centered Tuition Enhancement Funds and K-State Libraries.