THE NINETEENTH-CENTURY BEGINNINGS of 'WISDOM LITERATURE', and ITS TWENTY-FIRST-CENTURY END? Will Kynes on Reading My Title

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wisdom in Daniel and the Origin of Apocalyptic

WISDOM IN DANIEL AND THE ORIGIN OF APOCALYPTIC by GERALD H. WILSON University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia 30602 In this paper, I am concerned with the relationship of the book of Daniel and the biblical wisdom literature. The study draws its impetus from the belief of von Rad that apocalyptic is the "child" of wisdom (1965, II, pp. 304-15). My intent is to test von Rad's claim by a study of wisdom terminology in Daniel in order to determine whether, in fact, that book has its roots in the wisdom tradition. Adequate evidence has been gathered to demonstrate a robust connection between the nar ratives of Daniel 1-6 and mantic wisdom which employs the interpreta tion of dreams, signs and visions (Millier, 1972; Collins, 1975). Here I am concerned to dispell the continuing notion that apocalyptic as ex hibited in Daniel (especially in chapters 7-12) is the product of the same wisdom circles from which came the proverbial biblical books of Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, Job and the later Ben Sirach. 1 I am indebted to the work of Why bray ( 1974), who has dealt exhaustively with the terminology of biblical wisdom, and to the work of Crenshaw (1969), who, among others, has rightly cautioned that the presence of wisdom vocabulary is insufficient evidence of sapiential influence. 2 Whybray (1974, pp. 71-154) distinguishes four categories of wisdom terminology: a) words from the root J:ikm itself; b) other characteristic terms occurring only in the wisdom corpus (5 words); c) words char acteristic of wisdom, but occurring so frequently in other contexts as to render their usefulness in determining sapiential influence questionable (23 words); and d) words characteristic of wisdom, but occurring only occasionally in other OT traditions (10 words). -

1.1 Biblical Wisdom

JOB, ECCLESIASTES, AND THE MECHANICS OF WISDOM IN OLD ENGLISH POETRY by KARL ARTHUR ERIK PERSSON B. A., Hon., The University of Regina, 2005 M. A., The University of Regina, 2007 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (English) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) February 2014 © Karl Arthur Erik Persson, 2014 Abstract This dissertation raises and answers, as far as possible within its scope, the following question: “What does Old English wisdom literature have to do with Biblical wisdom literature?” Critics have analyzed Old English wisdom with regard to a variety of analogous wisdom cultures; Carolyne Larrington (A Store of Common Sense) studies Old Norse analogues, Susan Deskis (Beowulf and the Medieval Proverb Tradition) situates Beowulf’s wisdom in relation to broader medieval proverb culture, and Charles Dunn and Morton Bloomfield (The Role of the Poet in Early Societies) situate Old English wisdom amidst a variety of international wisdom writings. But though Biblical wisdom was demonstrably available to Anglo-Saxon readers, and though critics generally assume certain parallels between Old English and Biblical wisdom, none has undertaken a detailed study of these parallels or their role as a precondition for the development of the Old English wisdom tradition. Limiting itself to the discussion of two Biblical wisdom texts, Job and Ecclesiastes, this dissertation undertakes the beginnings of such a study, orienting interpretation of these books via contemporaneous reception by figures such as Gregory the Great (Moralia in Job, Werferth’s Old English translation of the Dialogues), Jerome (Commentarius in Ecclesiasten), Ælfric (“Dominica I in Mense Septembri Quando Legitur Job”), and Alcuin (Commentarius Super Ecclesiasten). -

Wisdom Literature

Wisdom Literature What is Wisdom Literature? “Wisdom literature” is the generic label for the books of Proverbs, Ecclesiastes (=Qoheleth) and Job in the Hebrew Bible. Two other major wisdom books, the Book of Ben Sira (=Ecclesiasticus) and the Wisdom of Solomon, are found in the Apocrypha, but are accepted as canonical in the Catholic tradition. Some psalms (e.g. 1, 19, 119) are regarded as “wisdom psalms” by analogy with the main wisdom books, and other similar writings are found in the Dead Sea Scrolls. The label derives simply from the fact that “wisdom” and “folly” are discussed frequently in these books. The designation is an old one, going back at least to St. Augustine. Wisdom is instructional literature, in which direct address is the norm. It may consist of single sentences, proverbial or hortatory, strung together, or of longer poems and discourses, some of which tend toward the philosophical. From early times, wisdom was associated with King Solomon. According to 1 Kings 4:29-34, God gave Solomon very great wisdom, discernment, and breadth of understanding as vast as the sand on the sea-shore, so that Solomon’s wisdom surpassed the wisdom of all the people of the east, and all the wisdom of Egypt . .He composed three thousand proverbs, and his songs numbered a thousand and five. He would speak of trees, from the cedar that is in the Lebanon to the hyssop that grows in the wall; he would speak of trees, from the cedar that is in the Lebanon to the hyssop that grows in the wall; he would speak of animals, and birds, and reptiles, and fish. -

The King Who Will Rule the World the Writings (Ketuvim) Mako A

David’s Heir – The King Who Will Rule the World The Writings (Ketuvim) Mako A. Nagasawa Last modified: September 24, 2009 Introduction: The Hero Among ‘the gifts of the Jews’ given to the rest of the world is a hope: A hope for a King who will rule the world with justice, mercy, and peace. Stories and legends from long ago seem to suggest that we are waiting for a special hero. However, it is the larger Jewish story that gives very specific meaning and shape to that hope. The theme of the Writings is the Heir of David, the King who will rule the world. This section of Scripture is very significant, especially taken all together as a whole. For example, not only is the Book of Psalms a personal favorite of many people for its emotional expression, it is a prophetic favorite of the New Testament. The Psalms, written long before Jesus, point to a King. The NT quotes Psalms 2, 16, and 110 (Psalm 110 is the most quoted chapter of the OT by the NT, more frequently cited than Isaiah 53) in very important places to assert that Jesus is the King of Israel and King of the world. The Book of Chronicles – the last book of the Writings – points to a King. He will come from the line of David, and he will rule the world. Who will that King be? What will his life be like? Will he usher in the life promised by God to Israel and the world? If so, how? And, what will he accomplish? How worldwide will his reign be? How will he defeat evil on God’s behalf? Those are the major questions and themes found in the Writings. -

The Reception of the Book of Daniel (And

The Reception of the Book of Daniel (and Danielic Literature) in the Early Church Wisdom and Apocalypticism Section SBL Annual Meeting in Washington, November 18-22, 2006 by Gerbern S. Oegema, McGill University 3520 University Street, Montreal, QC. Canada H3A 2A7 all rights reserved: for seminar use only. Any quotation from or reference to this paper should be made only with permission of author: [email protected] Abstract Whereas cosmogony has traditionally been seen as a topic dealt with primarily in wisdom literature, and eschatology, a field mostly focused upon in apocalyptic literature, the categorization of apocryphal and pseudepigraphic writings into sapiential, apocalyptic, and other genres has always been considered unsatisfactory. The reason is that most of the Pseudepigrapha share many elements of various genres and do not fit into only one genre. The Book of Daniel, counted among the Writings of the Hebrew Bible and among the Prophets in the Septuagint as well as in the Christian Old Testament, is such an example. Does it deal with an aspect of Israel’s origin and history, a topic dealt mostly dealt with in sapiential thinking, or only with its future, a question foremost asked with an eschatological or apocalyptic point of view? The answer is that the author sees part of the secrets of Israel’s future already revealed in its past. It is, therefore, in the process of investigating Israel’s history that apocalyptic eschatology and wisdom theology meet. This aspect is then stressed even more in the later reception history of the Book of Daniel as well as of writings ascribed to Daniel: if one wants to know something about Israel’s future in an ever-changing present situation, one needs to interpret the signs of the past. -

Syllabus, Deuterocanonical Books

The Deuterocanonical Books (Tobit, Judith, 1 & 2 Maccabees, Wisdom, Sirach, Baruch, and additions to Daniel & Esther) Caravaggio. Saint Jerome Writing (oil on canvas), c. 1605-1606. Galleria Borghese, Rome. with Dr. Bill Creasy Copyright © 2021 by Logos Educational Corporation. All rights reserved. No part of this course—audio, video, photography, maps, timelines or other media—may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage or retrieval devices without permission in writing or a licensing agreement from the copyright holder. Scripture texts in this work are taken from the New American Bible, revised edition © 2010, 1991, 1986, 1970 Confraternity of Christian Doctrine, Washington, D.C. and are used by permission of the copyright owner. All Rights Reserved. No part of the New American Bible may be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the copyright owner. 2 The Deuterocanonical Books (Tobit, Judith, 1 & 2 Maccabees, Wisdom, Sirach, Baruch, and additions to Daniel & Esther) Traditional Authors: Various Traditional Dates Written: c. 250-100 B.C. Traditional Periods Covered: c. 250-100 B.C. Introduction The Deuterocanonical books are those books of Scripture written (for the most part) in Greek that are accepted by Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches as inspired, but they are not among the 39 books written in Hebrew accepted by Jews, nor are they accepted as Scripture by most Protestant denominations. The deuterocanonical books include: • Tobit • Judith • 1 Maccabees • 2 Maccabees • Wisdom (also called the Wisdom of Solomon) • Sirach (also called Ecclesiasticus) • Baruch, (including the Letter of Jeremiah) • Additions to Daniel o “Prayer of Azariah” and the “Song of the Three Holy Children” (Vulgate Daniel 3: 24- 90) o Suzanna (Daniel 13) o Bel and the Dragon (Daniel 14) • Additions to Esther Eastern Orthodox churches also include: 3 Maccabees, 4 Maccabees, 1 Esdras, Odes (which include the “Prayer of Manasseh”) and Psalm 151. -

Proverbs Part One: Ten Instructions for the Wisdom Seeker

PROVERBS 67 Part One: Ten Instructions for the Wisdom Seeker Chapters 1-9 Introduction.Proverbs is generally regarded as the COMMENTARY book that best characterizes the Wisdom tradition. It is presented as a “guide for successful living.” Its PART 1: Ten wisdom instructions (Chapters 1-9) primary purpose is to teach wisdom. In chapters 1-9, we find a set of ten instructions, A “proverb” is a short saying that summarizes some aimed at persuading young minds about the power of truths about life. Knowing and practicing such truths wisdom. constitutes wisdom—the ability to navigate human relationships and realities. CHAPTER 1: Avoid the path of the wicked; Lady Wisdom speaks The Book of Proverbs takes its name from its first verse: “The proverbs of Solomon, the son of David.” “That men may appreciate wisdom and discipline, Solomon is not the author of this book which is a may understand words of intelligence; may receive compilation of smaller collections of sayings training in wise conduct….” (vv 2-3) gathered up over many centuries and finally edited around 500 B.C. “The fear of the Lord is the beginning of knowledge….” (v.7) In Proverbs we will find that certain themes or topics are dealt with several times, such as respect for Verses 1-7.In these verses, the sage or teacher sets parents and teachers, control of one’s tongue, down his goal: to instruct people in the ways of cautious trust of others, care in the selection of wisdom. friends, avoidance of fools and women with loose morals, practice of virtues such as humility, The ten instructions in chapters 1-9 are for those prudence, justice, temperance and obedience. -

Growing the Tree: Early Christian Mysticism, Angelomorphic Identity, and The

ABSTRACT (Re)growing the Tree: Early Christian Mysticism, Angelomorphic Identity, and the Shepherd of Hermas By Franklin Trammell This study analyzes the Shepherd of Hermas with a focus on those elements within the text that relate to the transformation of the righteous into the androgynous embodied divine glory. In so doing, Hermas is placed within the larger context of early Jewish and Christian mysticism and its specific traditions are traced back to the Jerusalem tradition evinced in the sayings source Q. Hermas is therefore shown to preserve a very old form of Christianity and an early form of Christian mysticism. It is argued that since Hermas’ revelatory visions of the Angel of the Lord and the divine House represent the object into which his community is being transformed, already in the present, and he provides a democratized praxis which facilitates their transformation and angelomorphic identity, he is operating within the realm of early Christian mysticism. Hermas’ implicit identification of the Ecclesia with Wisdom, along with his imaging of the righteous in terms of a vine and a Tree who are in exile and whose task it is to grow the Tree, is shown to have its earlier precedent in the Q source wherein Jesus and his followers take on an angelomorphic identity with the female Wisdom of the Temple and facilitate her restoration. Hermas’ tradition of the glory as a union of the Son of God and Wisdom is also shown to have its most direct contact with the Q source, in which Wisdom and the Son are understood to be eschatologically united in the transformation of the people of God. -

The Book of Proverbs: Wisdom for Life August 5Th, 2015 Text

The Book of Proverbs: Wisdom for Life August 5th, 2015 Text: Proverbs 1:1-7 Background/Theme: The book of Proverbs was written mainly by Solomon (known as Israel’s wisest king) yet some of the later sections were written by men named Lemuel and Agur (See Prov. 1:1). It was written during Solomon’s reign (970-930 B.C.). Solomon asked God for wisdom to rule God’s nation and God granted it (1 Kings 3:6-14). Proverbs along with Job, Psalms, Ecclesiastes, and Song of Solomon are known as the writings or “Wisdom Books” addressing practical living before God. The theme of Proverbs is wisdom (the skilled and right use of knowledge). The main purpose of this book is to teach wisdom to God’s people through the use of proverbs. The word Proverb means “to be like.” Therefore, Proverbs are short statements, which compare and contrast common, concrete images with life’s most profound truth. They are practical and point the way to godly character. These proverbs address subjects such as: life, family, friends, good judgment, and distinctions between the wise and foolish man. Proverbs is not a do-it-yourself success kit for the greedy but a guidebook for the godly. This starts with fearing the LORD. Memory Verse: Prov. 1:7 Outline: Ch 1-9-Solomon writes wisdom for younger people. Ch 10-24 - There is wisdom on various topics that apply to the average person. Ch 25-31 - Wisdom for leaders is provided. Tips for reading proverbs-Proverbs are statements of general truth and must not be taken as divine promises (Prov. -

The Old Testament: Part Thirteen Wisdom Books of the Bible

The Old Testament: Part Thirteen Wisdom Books of the Bible The following are some excerpts from a fuller experience and reason. The means of acquiring introduction to the Wisdom books of the bible. (For wisdom are through study, instruction, discipline, the complete introduction, see Article 66 on my reflection, meditation and counsel. He who hates Commentaries on the Books of the Old Testament.) wisdom is called a fool, sinner, ignorant, proud, wicked, and senseless. The message of the Wisdom There are five books in the Old Testament called teachers can be summed up in the words of St. Paul: “Wisdom books”: Job, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, “What things are true, whatever honorable, whatever Ecclesiasticus and Wisdom. In Catholic Bibles, the just, whatever holy, whatever lovable, whatever of Song of Songs and Psalms are also grouped in the good repute, if there be any virtue, if anything worthy Wisdom books section. of praise, think upon these things. And what you have The reader who moves from the historical or learned and received and heard and seen in me, these prophetical books of the Bible into the Wisdom books things practice (Phil.4:8-9); whether you eat or drink, will find him/herself in a different world. While the or do anything else, do all for the glory of God” (1Cor. Wisdom books differ among themselves in both style 10:31). and subject matter, they have in common the following characteristics: The Catholic Bible – Personal Study Edition offers the following short description for each of the seven books 1. They show minimum interest in the great themes contained in the Wisdom section of Catholic Bibles. -

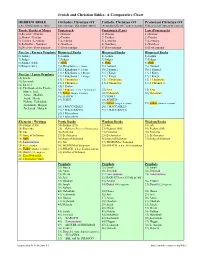

Hebrew and Christian Bibles: a Comparative Chart

Jewish and Christian Bibles: A Comparative Chart HEBREW BIBLE Orthodox Christian OT Catholic Christian OT Protestant Christian OT (a.k.a. TaNaK/Tanakh or Mikra) (based on longer LXX; various editions) (Alexandrian LXX, with 7 deutero-can. bks) (Cath. order, but 7 Apocrypha removed) Torah / Books of Moses Pentateuch Pentateuch (Law) Law (Pentateuch) 1) Bereshit / Genesis 1) Genesis 1) Genesis 1) Genesis 2) Shemot / Exodus 2) Exodus 2) Exodus 2) Exodus 3) VaYikra / Leviticus 3) Leviticus 3) Leviticus 3) Leviticus 4) BaMidbar / Numbers 4) Numbers 4) Numbers 4) Numbers 5) Devarim / Deuteronomy 5) Deuteronomy 5) Deuteronomy 5) Deuteronomy Nevi’im / Former Prophets Historical Books Historical Books Historical Books 6) Joshua 6) Joshua 6) Joshua 6) Joshua 7) Judges 7) Judges 7) Judges 7) Judges 8) Samuel (1&2) 8) Ruth 8) Ruth 8) Ruth 9) Kings (1&2) 9) 1 Kingdoms (= 1 Sam) 9) 1 Samuel 9) 1 Samuel 10) 2 Kingdoms (= 2 Sam) 10) 2 Samuel 10) 2 Samuel 11) 3 Kingdoms (= 1 Kings) 11) 1 Kings 11) 1 Kings Nevi’im / Latter Prophets 12) 4 Kingdoms (= 2 Kings) 12) 2 Kings 12) 2 Kings 10) Isaiah 13) 1 Chronicles 13) 1 Chronicles 13) 1 Chronicles 11) Jeremiah 14) 2 Chronicles 14) 2 Chronicles 14) 2 Chronicles 12) Ezekiel 15) 1 Esdras 13) The Book of the Twelve: 16) 2 Esdras (= Ezra + Nehemiah) 15) Ezra 15) Ezra Hosea, Joel, 17) Esther (longer version) 16) Nehemiah 16) Nehemiah Amos, Obadiah, 18) JUDITH 17) TOBIT Jonah, Micah, 19) TOBIT 18) JUDITH Nahum, Habakkuk, 19) Esther (longer version) 17) Esther (shorter version) Zephaniah, Haggai, 20) 1 MACCABEES 20) -

A Thematic Study of Doctrines on Death and Afterlife According to Targum Qohelet

A Thematic Study of Doctrines on Death and Afterlife according to Targum Qohelet By LAWRENCE RONALD LINCOLN DISSERTATION Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PHD in Ancient Cultures FACULTY OF ARTS AND SOCIAL SCIENCES PROMOTER: PROF JOHANN COOK April 2019 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Declaration By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. April 2019 Copyright © 2019 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved ii Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Abstract This dissertation examined how the Targum radically transformed Qohelet’s pessimistic, secular and cynical views on the human condition by introducing a composite rabbinical theology throughout the translation with the purpose of refuting the futility of human existence and the finality of death. The Targum overturned the personal observations of Qohelet and in its place proposed a practical guide for the living according to the principles of rabbinic theological principles. While BibQoh provided few if any solutions for the many pitfalls and challenges of life and lacking any clear references to an eschatology, the Targum on the other hand promoted the promise of everlasting life as a model for a beatific eschatological future. The dissertation demonstrated how the targumist exploited a specific translation strategy to introduce rabbinic ideologies to present the targum as an alternative context to the ideologies of wisdom literature as presented in Biblical Qohelet.