Download This PDF File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

To Make Claims About Or Even Adequately Understand the "True Nature" of Organizations Or Leadership Is a Monumental Task

BooK REvrnw: HERE CoMES EVERYBODY: THE PowER OF ORGANIZING WITHOUT ORGANIZATIONS (Clay Shirky, Penguin Press, 2008. Hardback, $25.95] -CHRIS FRANCOVICH GONZAGA UNIVERSITY To make claims about or even adequately understand the "true nature" of organizations or leadership is a monumental task. To peer into the nature of the future of these complex phenomena is an even more daunting project. In this book, however, I think we have both a plausible interpretation of organ ization ( and by implication leadership) and a rare glimpse into what we are becoming by virtue of our information technology. We live in a complex, dynamic, and contingent environment whose very nature makes attributing cause and effect, meaning, or even useful generalizations very difficult. It is probably not too much to say that historically the ability to both access and frame information was held by the relatively few in a system and structure whose evolution is, in its own right, a compelling story. Clay Shirky is in the enviable position of inhabiting the domain of the technological elite, as well as being a participant and a pioneer in the social revolution that is occurring partly because of the technologies and tools invented by that elite. As information, communication, and organization have grown in scale, many of our scientific, administrative, and "leader-like" responses unfortu nately have remained the same. We find an analogous lack of appropriate response in many followers as evidenced by large group effects manifested through, for example, the response to advertising. However, even that herd like consumer behavior seems to be changing. Markets in every domain are fragmenting. -

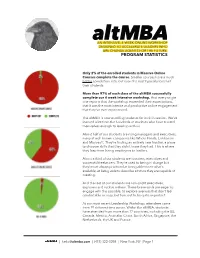

Program Statistics

AN INTENSIVE, 4-WEEK ONLINE WORKSHOP DESIGNED TO ACCELERATE LEADERS WHO ARE CHANGE AGENTS FOR THE FUTURE. PROGRAM STATISTICS Only 2% of the enrolled students in Massive Online Courses complete the course. Smaller courses have a much better completion rate, but even the best typically lose half their students. More than 97% of each class of the altMBA successfully complete our 4 week intensive workshop. And every single one reports that the workshop exceeded their expectations, that it was the most intense and productive online engagement that they’ve ever experienced. The altMBA is now enrolling students for its fifth session. We’ve learned a lot from the hundreds of students who have trusted themselves enough to level up with us. About half of our students are rising managers and executives, many at well-known companies like Whole Foods, Lululemon and Microsoft. They’re finding an entirely new frontier, a place to discover skills that they didn’t know they had. This is where they leap from being employees to leaders. About a third of our students are founders, executives and successful freelancers. They’re used to being in charge but they’re not always practiced at being able to see what’s available, at being able to describe a future they are capable of creating. And the rest of our students are non-profit executives, explorers and ruckus makers. These brave souls are eager to engage with the possible, to explore avenues that don’t feel comfortable or easy, but turn out to be quite important. At our most recent Leadership Workshop, attendees came from 19 different time zones. -

Crowdsourcing Metadata for Library and Museum Collections Using a Taxonomy of Flickr User Behavior

CROWDSOURCING METADATA FOR LIBRARY AND MUSEUM COLLECTIONS USING A TAXONOMY OF FLICKR USER BEHAVIOR A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science by Evan Fay Earle January 2014 © 2014 Evan Fay Earle ABSTRACT Library and museum staff members are faced with having to create descriptions for large numbers of items found within collections. Immense collections and a shortage of staff time prevent the description of collections using metadata at the item level. Large collections of photographs may contain great scholarly and research value, but this information may only be found if items are described in detail. Without detailed descriptions, the items are much harder to find using standard web search techniques, which have become the norm for searching library and museum collection catalogs. To assist with metadata creation, institutions can attempt to reach out to the public and crowdsource descriptions. An example of crowdsourced description generation is the website, Flickr, where the entire user community can comment and add metadata information in the forms of tags to other users’ images. This paper discusses some of the problems with metadata creation and provides insight on ways in which crowdsourcing can benefit institutions. Through an analysis of tags and comments found on Flickr, behaviors are categorized to show a taxonomy of users. This information is used in conjunction with survey data in an effort to show if certain types of users have characteristics that are most beneficial to enhancing metadata in existing library and museum collections. -

A Shared Digital Future? Will the Possibilities for Mass Creativity on the Internet Be Realized Or Squandered, Asks Tony Hey

NATURE|Vol 455|4 September 2008 OPINION A shared digital future? Will the possibilities for mass creativity on the Internet be realized or squandered, asks Tony Hey. The potential of the Internet and the attack, such as that dramatized in web for creating a better, more inno- the 2007 movie Live Free or Die vative and collaborative future is Hard (also titled Die Hard 4.0). discussed in three books. Together, Zittrain argues that security they make a convincing case that problems could lead to the ‘appli- we are in the midst of a revolution ancization’ of the Internet, a return as significant as that brought about to managed interfaces and a trend by Johannes Gutenberg’s invention towards tethered devices, such as of movable type. Sharing many the iPhone and Blackberry, which WATTENBERG VIÉGAS/M. BERTINI F. examples, notably Wikipedia and are subject to centralized control Linux, the books highlight different and are much less open to user concerns and opportunities. innovation. He also argues that The Future of the Internet the shared technologies that make addresses the legal issues and dan- up Web 2.0, which are reliant on gers involved in regulating the Inter- remote services offered by commer- net and the web. Jonathan Zittrain, cial organizations, may reduce the professor of Internet governance user’s freedom for innovation. I am and regulation at the Univ ersity of unconvinced that these technologies Oxford, UK, defends the ability of will kill generativity: smart phones the Internet and the personal com- are just computers, and specialized puter to produce “unanticipated services, such as the image-hosting change through unfiltered con- An editing history of the Wikipedia entry on abortion shows the numerous application SmugMug, can be built tributions from broad and varied contributors (in different colours) and changes in text length (depth). -

A Group Is Its Own Worst Enemy 1

Clay Shirky A GROUP IS ITS OWN WORST ENEMY 1 In the late 1980s, software went through a major transition. Before about 1985, the primary goal of software was making it possible to solve a problem, by any means necessary. Do you need to punch cards with your input data? No big deal. A typo on one card means you have to throw it away and start over? No problem. Humans will bend to the machines, like Charlie Chaplin in Modern Times. Suddenly with personal computers the bar was raised. It wasn’t enough just to solve the problem: you had to solve it easily, in a way that takes into account typical human frailties. The backspace key, for example, to compensate for human frailty, not to mention menus, icons, windows, and unlimited Undo. And we called this usability, and it was good. Lo and behold, when the software industry tried to hire experts in usability, they found that it was a new field, so nobody was doing this. There was this niche field in psychiatry called ergonom- ics, but it was mostly focused on things from the physical world, like finding the optimal height for a desk chair. Eventually usability came into its own as a first-class field of study, with self-trained practitioners and university courses, and no software project could be considered complete without at least a cursory glance at usability. 1. This is a lightly edited version of the keynote Clay Shirky gave on social software at the O’Reilly Emerging Technology conference in Santa Clara on April 24, 2003. -

The Rise of Twitter Fiction…………………………………………………………1

Twitter Fiction: A Shift in Author Function Hilary Hyman Twitter fiction, an example of twenty-first century digital narrative, allows authors to experiment with literary form, production, and dissemination as they engage readers through a communal network. Twitter offers creative space for both professionals and amateurs to publish fiction digitally, enabling greater collaboration among authors and readers. Examining Jennifer Egan’s “Black Box” and selected Twitter stories from Junot Diaz, Teju Cole, and Elliott Holt, this thesis establishes two distinct types of Twitter fiction—one produced for the medium and one produced through it—to consider how Twitter’s present feed and character limit fosters a uniquely interactive reading experience. As the conversational medium calls for present engagement with the text and with the author, Twitter promotes newly elastic relationships between author and reader that renegotiate the former boundaries between professionals and amateurs. This thesis thus considers how works of Twitter fiction transform the traditional author function and pose new questions regarding digital narrative’s modes of existence, circulation, and appropriation. As digital narrative makes its way onto democratic forums, a shifted author function leaves us wondering what it means to be an author in the digital age. Twitter Fiction: A Shift in Author Function Hilary Anne Hyman Twitter Fiction: A Shift in Author Function Hilary Anne Hyman An Undergraduate Honors Thesis Submitted to the Department of English at Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in the Major April 18, 2016 Thesis Adviser: Vera Kutzinski Date Second Reader: Haerin Shin Date Program Director: Teresa Goddu Date For My Parents Acknowledgements I would like to acknowledge Professor Teresa Goddu for shaping me into the writer I have become. -

Presentation Slides Plus Notes Are Available As A

Maximising opportunities in the online marketplace Web 2.0 and beyond Image: jimkster @ Flickr - http://flickr.com/photos/jimkster/2723151022/ Image: jimkster @ Flickr - http://flickr.com/photos/jimkster/2723151022/ Image: jimkster @ Flickr - http://flickr.com/photos/jimkster/2723151022/ Image: jimkster @ Flickr - http://flickr.com/photos/jimkster/2723151022/ Image: jimkster @ Flickr - http://flickr.com/photos/jimkster/2723151022/ Image: jimkster @ Flickr - http://flickr.com/photos/jimkster/2723151022/ dot Image: ten safe frogs @ flickr - http://flickr.com/photos/tensafefrogs/724682692/ Image: ten safe frogs @ flickr - http://flickr.com/photos/tensafefrogs/724682692/ Letʼs start by looking at what “Web 2.0” really is... Letʼs start by looking at what “Web 2.0” really is... RSS Really Simple Syndication • The “glue” between systems (for content syndication) Further reading: • Common Craft - RSS in plain English: http://tinyurl.com/2s9uat RSS Web applications • Gmail is just one of the many web applications • Facilitates collaboration and other network benefits RSS Web applications Developer tools Web services, AJAX, agile programming • Asynchronous Javascript And XML • Collection of existing technologies that turn a browser into a “rich client” • More responsive experience for users • Agile programming methodology - quick to market, iterative development Further reading: • Jesse James Garret (Adaptive Path) - Ajax: A New Approach to Web Applications:http://tinyurl.com/29nlsm • 37signals - Getting Real: http://gettingreal.37signals.com/ Image: dizid @ flickr - http://flickr.com/photos/dizid/96491998/ Itʼs the combination of technology and the social effects that they enable. Image: dizid @ flickr - http://flickr.com/photos/dizid/96491998/ Further reading: • Clay Shirky - “Here comes everybody”: http://tr.im/9dt • The value increases the more “nodes” that are in the network (“A world of ends”) • Provide personal value first.. -

Here Comes Everybody by Clay Shirky

HERE COMES EVERYBODY THE POWER OF ORGANIZING WITHOUT ORGANIZATIONS CLAY SHIRKY ALLEN LANE an imprint of PENGUIN BOOKS ALLEN LANE Published by the Penguin Group Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London we2R ORL, England Penguin Group IUSA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA Penguin Group ICanada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3 la division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.) Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephen's Green, Dublin 2, Ireland la division of Penguin Books Ltd) Penguin Group IAustralia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell. Victoria 3124. Austra1ia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd) Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, II Community Centre, Panchsheel Park. New Delhi - 110 017, India Penguin Group INZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, North Shore 0632, New Zealand la division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd) Penguin Books ISouth Africa) IPty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London we2R ORL, England www.penguin.com First published in the United States of America by The Penguin Press, a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc. 2008 First published in Great Britain by Allen Lane 2008 Copyright © Clay Shirky, 2008 The moral right of the author has been asserted AU rights reserved Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise). without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book Printed in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, St Ives pic A CI P catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library www.greenpenguin.co.uk Penguin Books is committed (0 a sustainable future D MIXed Sources for our business, our readers and our planer. -

THE ARGUMENT ENGINE While Wikipedia Critics Are Becoming Ever More Colorful in Their Metaphors, Wikipedia Is Not the Only Reference Work to Receive Such Scrutiny

14 CRITICAL POINT OF VIEW A Wikipedia Reader ENCYCLOPEDIC KNOWLEDGE 15 THE ARGUMENT ENGINE While Wikipedia critics are becoming ever more colorful in their metaphors, Wikipedia is not the only reference work to receive such scrutiny. To understand criticism about Wikipedia, JOSEPH REAGLE especially that from Gorman, it is useful to first consider the history of reference works relative to the varied motives of producers, their mixed reception by the public, and their interpreta- tion by scholars. In a Wired commentary by Lore Sjöberg, Wikipedia production is characterized as an ‘argu- While reference works are often thought to be inherently progressive, a legacy perhaps of ment engine’ that is so powerful ‘it actually leaks out to the rest of the web, spontaneously the famous French Encyclopédie, this is not always the case. Dictionaries were frequently forming meta-arguments about itself on any open message board’. 1 These arguments also conceived of rather conservatively. For example, when the French Academy commenced leak into, and are taken up by the champions of, the print world. For example, Michael Gor- compiling a national dictionary in the 17th century, it was with the sense that the language man, former president of the American Library Association, uses Wikipedia as an exemplar had reached perfection and should therefore be authoritatively ‘fixed’, as if set in stone. 6 of a dangerous ‘Web 2.0’ shift in learning. I frame such criticism of Wikipedia by way of a Also, encyclopedias could be motivated by conservative ideologies. Johann Zedler wrote in historical argument: Wikipedia, like other reference works before it, has triggered larger social his 18th century encyclopedia that ‘the purpose of the study of science… is nothing more anxieties about technological and social change. -

Richard S. Salant Lecture on Freedom of the Press with Clay Shirky

Richard S. Salant Lecture on Freedom of the Press with Clay Shirky 2011 Table of Contents History of the Richard S. Salant Lecture .............................................................5 Biography of Clay Shirky ......................................................................................7 Introduction by Alex S. Jones ...............................................................................9 Richard S. Salant Lecture on Freedom of the Press by Clay Shirky ...............................................................................................10 Fourth Annual Richard S. Salant Lecture 3 History In 2007, the estate of Dr. Frank Stanton, former president of CBS, provided funding for an annual lecture in honor of his longtime friend and colleague, Mr. Richard S. Salant, a lawyer, broadcast media executive, ardent defender of the First Amend- ment and passionate leader of broadcast ethics and news standards. Frank Stanton was a central figure in the develop- ment of television broadcasting. He became president of CBS in January 1946, a position he held for 27 years. A staunch advocate of First Amendment rights, Stanton worked to ensure that broadcast journalism received protection equal to that received by the print press. In testimony before a U.S. Congressional com- mittee when he was ordered to hand over material from an investigative report called “The Selling of the Pentagon,” Stanton said that the order amounted to an infringement of free speech under the First Amendment. He was also instrumental in assembling the first televised presidential debate in 1960. In 1935, Stanton received a doctorate from Ohio State University and was hired by CBS. He became head of CBS’s research department in 1938, vice president and general manager in 1945, and in 1946, at the age of 38, was made president of the company. -

The Effects of Social Media on Democratization

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Dissertations and Theses City College of New York 2012 The Effects of Social Media on Democratization Melissa Spinner CUNY City College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cc_etds_theses/110 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] The Effects of Social Media on Democratization Melissa Spinner Date: August 2011 Master’s Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of International Affairs at the City College of New York Advisor: Bruce Cronin Table of Contents Introduction..............................................................................................................1 Chapter 1: Defining and Understanding Democratization.....................................16 Chapter 2: Defining and Understanding New Technologies .................................30 Chapter 3: Infrastructure and Contextual Conditions that Lead to Democratization ......49 Chapter 4: Evidence of the Link Between Social Media and Democratization ....68 Chapter 5: The Philippines: How Text Messaging Ousted a President.................85 Chapter 6: Egypt: The Beginning of Democratization ..........................................92 Chapter 7: Disputing the Dissenters ......................................................................99 Conclusion ...........................................................................................................121 -

The Long Tail / Chris Anderson

THE LONG TAIL Why the Future of Business Is Selling Less of More Enter CHRIS ANDERSON To Anne CONTENTS Acknowledgments v Introduction 1 1. The Long Tail 15 2. The Rise and Fall of the Hit 27 3. A Short History of the Long Tail 41 4. The Three Forces of the Long Tail 52 5. The New Producers 58 6. The New Markets 85 7. The New Tastemakers 98 8. Long Tail Economics 125 9. The Short Head 147 iv | CONTENTS 10. The Paradise of Choice 168 11. Niche Culture 177 12. The Infinite Screen 192 13. Beyond Entertainment 201 14. Long Tail Rules 217 15. The Long Tail of Marketing 225 Coda: Tomorrow’s Tail 247 Epilogue 249 Notes on Sources and Further Reading 255 Index 259 About the Author Praise Credits Cover Copyright ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This book has benefited from the help and collaboration of literally thousands of people, thanks to the relatively open process of having it start as a widely read article and continue in public as a blog of work in progress. The result is that there are many people to thank, both here and in the chapter notes at the end of the book. First, the person other than me who worked the hardest, my wife, Anne. No project like this could be done without a strong partner. Anne was all that and more. Her constant support and understanding made this possible, and the price was significant, from all the Sundays taking care of the kids while I worked at Starbucks to the lost evenings, absent vacations, nights out not taken, and other costs of an all-consuming project.