The Rise of Twitter Fiction…………………………………………………………1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

To Make Claims About Or Even Adequately Understand the "True Nature" of Organizations Or Leadership Is a Monumental Task

BooK REvrnw: HERE CoMES EVERYBODY: THE PowER OF ORGANIZING WITHOUT ORGANIZATIONS (Clay Shirky, Penguin Press, 2008. Hardback, $25.95] -CHRIS FRANCOVICH GONZAGA UNIVERSITY To make claims about or even adequately understand the "true nature" of organizations or leadership is a monumental task. To peer into the nature of the future of these complex phenomena is an even more daunting project. In this book, however, I think we have both a plausible interpretation of organ ization ( and by implication leadership) and a rare glimpse into what we are becoming by virtue of our information technology. We live in a complex, dynamic, and contingent environment whose very nature makes attributing cause and effect, meaning, or even useful generalizations very difficult. It is probably not too much to say that historically the ability to both access and frame information was held by the relatively few in a system and structure whose evolution is, in its own right, a compelling story. Clay Shirky is in the enviable position of inhabiting the domain of the technological elite, as well as being a participant and a pioneer in the social revolution that is occurring partly because of the technologies and tools invented by that elite. As information, communication, and organization have grown in scale, many of our scientific, administrative, and "leader-like" responses unfortu nately have remained the same. We find an analogous lack of appropriate response in many followers as evidenced by large group effects manifested through, for example, the response to advertising. However, even that herd like consumer behavior seems to be changing. Markets in every domain are fragmenting. -

Collaborative Storytelling 2.0: a Framework for Studying Forum-Based Role-Playing Games

COLLABORATIVE STORYTELLING 2.0: A FRAMEWORK FOR STUDYING FORUM-BASED ROLE-PLAYING GAMES Csenge Virág Zalka A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2017 Committee: Kristine Blair, Committee Co-Chair Lisa M. Gruenhagen Graduate Faculty Representative Radhika Gajjala, Committee Co-Chair Jeremy Wallach ii ABSTRACT Kristine Blair and Radhika Gajjala, Committee Co-Chairs Forum-based role-playing games are a rich, yet barely researched subset of text- based digital gaming. They are a form of storytelling where narratives are created through acts of play by multiple people in an online space, combining collaboration and improvisation. This dissertation acts as a pilot study for exploring these games in their full complexity at the intersection of play, narrative, and fandom. Building on theories of interactivity, digital storytelling, and fan fiction studies, it highlights forum games’ most unique features, and proves that they are is in no way liminal or secondary to more popular forms of role-playing. The research is based on data drawn from a large sample of forums of various genres. One hundred sites were explored through close textual analysis in order to outline their most common features. The second phase of the project consisted of nine months of participant observation on select forums, in order to gain a better understanding of how their rules and practices influence the emergent narratives. Participants from various sites contributed their own interpretations of forum gaming through a series of ethnographic interviews. This did not only allow agency to the observed communities to voice their thoughts and explain their practices, but also spoke directly to the key research question of why people are drawn to forum gaming. -

Roll 2D6 to Kill

1 Roll 2d6 to kill Neoliberal design and its affect in traditional and digital role-playing games Ruben Ferdinand Brunings August 15th, 2017 Table of contents 2 Introduction: Why we play 3. Part 1 – The history and neoliberalism of play & table-top role-playing games 4. Rules and fiction: play, interplay, and interstice 5. Heroes at play: Quantification, power fantasies, and individualism 7. From wargame to warrior: The transformation of violence as play 9. Risky play: chance, the entrepreneurial self, and empowerment 13. It’s ‘just’ a game: interactive fiction and the plausible deniability of play 16. Changing the rules, changing the game, changing the player 18. Part 2 – Technics of the digital game: hubristic design and industry reaction 21. Traditional vs. digital: a collaborative imagination and a tangible real 21. Camera, action: The digitalisation of the self and the representation of bodies 23. The silent protagonist: Narrative hubris and affective severing in Drakengard 25. Drakengard 3: The spectacle of violence and player helplessness 29. Conclusion: Games, conventionality, and the affective power of un-reward 32. References 36. Bibliography 38. Introduction: Why we play 3 The approach of violence or taboo in game design is a discussion that has historically been a controversial one. The Columbine shooting caused a moral panic for violent shooter video games1, the 2007 game Mass Effect made FOX News headlines for featuring scenes of partial nudity2, and the FBI kept tabs on Dungeons & Dragons hobbyists for being potential threats after the Unabomber attacks.3 The question ‘Do video games make people violent?’ does not occur within this thesis. -

Precarity and Belonging in the Work of Teju Cole

Luke Watson MA Dissertation 2019 Black Bodies in the Open City: Precarity and Belonging in the work of Teju Cole Luke Watson (WTSLUK001) A minor dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Master of Arts in English Language, Literature & Modernity Faculty of the Humanities University of Cape Town 2019 COMPULSORY DECLARATION This work hasUniversity not been previously submitted of inCape whole, or in part, Town for the award of any degree. It is my own work. Each significant contribution to, and quotation in, this dissertation from the work, or works, of other people has been attributed, and has been cited and referenced. Signature: Date: 4 June 2019 1 The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgementTown of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Cape Published by the University ofof Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University Luke Watson MA Dissertation 2019 Abstract This dissertation attempts to read Nigerian-American writer Teju Cole’s fiction and essays as sustained demonstrations of precarity, as theorised by Judith Butler in Precarious Life (2004). Though never directly cited by Cole, Butler’s articulation of a shared condition of bodily vulnerability and interdependency offers a generative critical framework through which to read Cole’s representations of black bodies as they move across space. By presenting the ‘black body’, rather than ‘black man’, as the preferred metonym for black people, Cole’s work, which I argue can be read as peculiar travel narratives, foregrounds the bodily dimension of black life, and develops an ambivalent storytelling mode to narrate the experiences of characters who encompass multiple spatialities and subjectivities. -

Low Effort Crowdsourcing

Low-effort Crowdsourcing: leveraging peripheral attention for crowd work Abstract Crowdsourcing systems leverage short bursts of focused attention from many contributors to achieve a goal. By requiring people’s full attention, existing crowdsourc- ing systems fail to leverage people’s cognitive surplus in the many settings for which they may be distracted, performing or waiting to perform another task, or barely paying attention. In this paper, we study opportunities for low-effort crowdsourcing that enable people to con- tribute to problem solving in such settings. We dis- cuss the design space for low-effort crowdsourcing, and through a series of prototypes, demonstrate interaction techniques, mechanisms, and emerging principles for enabling low-effort crowdsourcing. Figure 1: With a front-facing camera, the emotive voting in- Introduction terface ‘likes’ an image if you smile while the image is on the screen, and ‘dislikes’ if you frown. Faces are blurred for Crowdsourcing and human computation systems leverage anonymity. the cognitive surplus (Shirky 2010) of large numbers of peo- ple to achieve a goal. Existing systems accomplish this by providing entertainment through games with a purpose (von task. For a person walking to catch a bus, the act of taking Ahn and Dabbish 2008), requiring a microtask for access- out their phone, opening an app, and then performing a sim- ing content (von Ahn et al. 2008), and requesting tasks from ple task will likely already require more effort than people workers and volunteers without requiring long-term com- are willing to give in that situation. Leveraging any cognitive mitment from contributors. By capturing people’s attention surplus people may have in such settings will thus require and leveraging their efforts, systems such as the ESP game, accounting for people’s situational context, and introducing reCAPTCHA, and Mechanical Turk enable useful work to novel interaction techniques and mechanisms that can en- be completed by bringing together episodes of focused at- able effective contributions in spite of it. -

FORD-THESIS-2013.Pdf (2.359Mb)

Copyright by Kasey Crystal Ford 2013 The Thesis Committee for Kasey Crystal Ford Certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: Emergent Social Network Communities: Hashtags, Knowledge Building, and Communities of Practice APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Supervisor: Paul Resta George Veletsianos Emergent Social Network Communities: Hashtags, Knowledge Building, and Communities of Practice by Kasey Crystal Ford, B. A. Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin May 2013 Dedication For Blake—I’m the luckiest. Acknowledgements I would like to thank my advisor, Dr. Paul Resta, for all of his helpful insights, thoughtful guidance, and Skype conversations. My research topic is thanks in no small part to Dr. George Veletsianos, whose work and suggestions inspired me. This project would not have been completed without them. This journey also made possible by my colleagues, supervisors, peers, and friends who supported me and informed my work. I am pleased to know such talented and passionate people. Of course, I would like to thank my family. To my parents, siblings, and in-laws for sending encouragement. My daughter, Molly Sunshine, was born midway through this process and instilled in me why this work is important. Most of my gratitude goes to my husband, Blake, for running a household by himself, letting me sleep when I was tired, feeding me when I was hungry, and most importantly discussing everything from technology to philosophy on car trips, while folding clothes, and in the middle of the night. -

Program Statistics

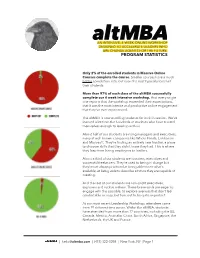

AN INTENSIVE, 4-WEEK ONLINE WORKSHOP DESIGNED TO ACCELERATE LEADERS WHO ARE CHANGE AGENTS FOR THE FUTURE. PROGRAM STATISTICS Only 2% of the enrolled students in Massive Online Courses complete the course. Smaller courses have a much better completion rate, but even the best typically lose half their students. More than 97% of each class of the altMBA successfully complete our 4 week intensive workshop. And every single one reports that the workshop exceeded their expectations, that it was the most intense and productive online engagement that they’ve ever experienced. The altMBA is now enrolling students for its fifth session. We’ve learned a lot from the hundreds of students who have trusted themselves enough to level up with us. About half of our students are rising managers and executives, many at well-known companies like Whole Foods, Lululemon and Microsoft. They’re finding an entirely new frontier, a place to discover skills that they didn’t know they had. This is where they leap from being employees to leaders. About a third of our students are founders, executives and successful freelancers. They’re used to being in charge but they’re not always practiced at being able to see what’s available, at being able to describe a future they are capable of creating. And the rest of our students are non-profit executives, explorers and ruckus makers. These brave souls are eager to engage with the possible, to explore avenues that don’t feel comfortable or easy, but turn out to be quite important. At our most recent Leadership Workshop, attendees came from 19 different time zones. -

Emhs 9Th Summer Reading 1

Annotation Directions: EMHS 9TH SUMMER READING 1. Make a point of underlining the two most important ideas in each “column” of reading. Each year, students at EMHS do summer reading. You can underline a single phrase or a couple Reading over the summer keeps one’s mind “awake” of sentences, but please choose your selections and provides your class with an immediate platform carefully. to work on from the first day of school. The material for this packet was selected for its subject matter and 2. Of the two ideas you underline in each column, relevance to you. select the most important one and rephrase it at the bottom of the page in your own words. Please make a point of reading all six of the articles 3. When you finish an article, review your contained in this packet. Since there are several annotations. On a separate sheet of paper, different pieces, you can break this reading up as write down the “takeaway points” for each your summer schedule allows. All articles should article—the most important ideas. be read and annotated by the first day of school. Please bring this packet with you on There are many online sources to further explain the first day of school. how to annotate a text. When you come to school on the first day, this packet should be completely read This packet should be printed out and read carefully. and annotated. In addition, you should have You should always read with a pen or pencil and use your takeaway points on a separate sheet of annotation strategies to help yourself make sense paper completed. -

Crowdsourcing Metadata for Library and Museum Collections Using a Taxonomy of Flickr User Behavior

CROWDSOURCING METADATA FOR LIBRARY AND MUSEUM COLLECTIONS USING A TAXONOMY OF FLICKR USER BEHAVIOR A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science by Evan Fay Earle January 2014 © 2014 Evan Fay Earle ABSTRACT Library and museum staff members are faced with having to create descriptions for large numbers of items found within collections. Immense collections and a shortage of staff time prevent the description of collections using metadata at the item level. Large collections of photographs may contain great scholarly and research value, but this information may only be found if items are described in detail. Without detailed descriptions, the items are much harder to find using standard web search techniques, which have become the norm for searching library and museum collection catalogs. To assist with metadata creation, institutions can attempt to reach out to the public and crowdsource descriptions. An example of crowdsourced description generation is the website, Flickr, where the entire user community can comment and add metadata information in the forms of tags to other users’ images. This paper discusses some of the problems with metadata creation and provides insight on ways in which crowdsourcing can benefit institutions. Through an analysis of tags and comments found on Flickr, behaviors are categorized to show a taxonomy of users. This information is used in conjunction with survey data in an effort to show if certain types of users have characteristics that are most beneficial to enhancing metadata in existing library and museum collections. -

Addition to Summer Letter

May 2020 Dear Student, You are enrolled in Advanced Placement English Literature and Composition for the coming school year. Bowling Green High School has offered this course since 1983. I thought that I would tell you a little bit about the course and what will be expected of you. Please share this letter with your parents or guardians. A.P. Literature and Composition is a year-long class that is taught on a college freshman level. This means that we will read college level texts—often from college anthologies—and we will deal with other materials generally taught in college. You should be advised that some of these texts are sophisticated and contain mature themes and/or advanced levels of difficulty. In this class we will concentrate on refining reading, writing, and critical analysis skills, as well as personal reactions to literature. A.P. Literature is not a survey course or a history of literature course so instead of studying English and world literature chronologically, we will be studying a mix of classic and contemporary pieces of fiction from all eras and from diverse cultures. This gives us an opportunity to develop more than a superficial understanding of literary works and their ideas. Writing is at the heart of this A.P. course, so you will write often in journals, in both personal and researched essays, and in creative responses. You will need to revise your writing. I have found that even good students—like you—need to refine, mature, and improve their writing skills. You will have to work diligently at revising major essays. -

I Never Took Myself Seriously As a Writer Until I Studied at Macquarie.” LIANE MORIARTY MACQUARIE GRADUATE and BEST-SELLING AUTHOR

2 swf.org.au RESEARCH & ENGAGEMENT 1817 - 2017 luxury property sales and rentals THE UN OF ITE L D A S R T E A T N E E S G O E F T A A M L E U R S I N C O A ●C ● SYDNEY THE LIFTED BROW Welcome 3 SWF 2017 swf.org.au A Message from the Artistic Director Contents eading can be a mixed blessing. For In a special event, writer and photographer 4-15 anyone who has had the misfortune Bill Hayes talks to Slate’s Stephen Metcalf about City & Walsh Bay to glance at the headlines recently, Insomniac City: New York, Oliver, and Me, an the last few months have felt like a intimate love letter to New York and his late Guest Curators 4 long fever dream, for reasons that partner, beloved writer and neurologist extend far beyond the outcome of the Oliver Sacks. R Bernadette Brennan has delved into 7 US Presidential election or Brexit. Nights at Walsh Bay More than 20 million refugees are on the move the career of one of Australia’s most adept and another 40 million people are displaced in and admired authors, Helen Garner, with Thinking Globally 11 their own countries, in the largest worldwide A Writing Life. An all-star cast of Garner humanitarian crisis since 1945. admirers – Annabel Crabb, Benjamin Law Scientists announced that the Earth reached and Fiona McFarlane – will join Bernadette City & Walsh Bay its highest temperatures in 2016 – for the third in conversation with Rebecca Giggs about year in a row. -

Networked Activism

\\server05\productn\H\HLH\22-2\HLH208.txt unknown Seq: 1 25-AUG-09 8:28 Networked Activism Molly Beutz Land* The same technologies that groups of ordinary citizens are using to write operating systems and encyclopedias are fostering a quiet revolution in an- other area—social activism. On websites such as Avaaz.org and Wikipedia, citizens are forming groups to report on human rights violations and organ- ize email writing campaigns, activities formerly the prerogative of profes- sionals. Because the demands of human rights work often require organizations to professionalize in order to be successful in their advocacy, human rights provides an ideal case study for evaluating the effect of low- ered barriers to online group formation on citizen participation in activism. This article considers whether the participatory potential of technology can be used to both broaden the mobilization of ordinary citizens in human rights advocacy and provide opportunities for individuals to become more deeply involved in the work. Existing online advocacy efforts reveal a de facto inverse relationship be- tween broad mobilization and deep participation. Large groups mobilize many individuals, but each of those individuals has only a limited ability to participate in decisions about the group’s goals or methods. This inverse relationship is principally a problem of size. As groups grow in size, they may replicate the process of professionalization in order to avoid the problems that would be associated with decentralized decision-making. Thus, although we currently have the tools necessary for individuals to en- gage in advocacy without the need for professional organizations, we are still far from realizing an ideal of fully decentralized, user-generated activism.