Here Comes Everybody by Clay Shirky

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

To Make Claims About Or Even Adequately Understand the "True Nature" of Organizations Or Leadership Is a Monumental Task

BooK REvrnw: HERE CoMES EVERYBODY: THE PowER OF ORGANIZING WITHOUT ORGANIZATIONS (Clay Shirky, Penguin Press, 2008. Hardback, $25.95] -CHRIS FRANCOVICH GONZAGA UNIVERSITY To make claims about or even adequately understand the "true nature" of organizations or leadership is a monumental task. To peer into the nature of the future of these complex phenomena is an even more daunting project. In this book, however, I think we have both a plausible interpretation of organ ization ( and by implication leadership) and a rare glimpse into what we are becoming by virtue of our information technology. We live in a complex, dynamic, and contingent environment whose very nature makes attributing cause and effect, meaning, or even useful generalizations very difficult. It is probably not too much to say that historically the ability to both access and frame information was held by the relatively few in a system and structure whose evolution is, in its own right, a compelling story. Clay Shirky is in the enviable position of inhabiting the domain of the technological elite, as well as being a participant and a pioneer in the social revolution that is occurring partly because of the technologies and tools invented by that elite. As information, communication, and organization have grown in scale, many of our scientific, administrative, and "leader-like" responses unfortu nately have remained the same. We find an analogous lack of appropriate response in many followers as evidenced by large group effects manifested through, for example, the response to advertising. However, even that herd like consumer behavior seems to be changing. Markets in every domain are fragmenting. -

Download Itunes About Journalism to Propose Four Use—Will Be Very Different

Nieman Reports THE NIEMAN FOUNDATION FOR JOURNALISM AT HARVARD UNIVERSITY VOL. 62 NO. 4 WINTER 2008 4 The Search for True North: New Directions in a New Territory Spiking the Newspaper to Follow the Digital Road 5 If Murder Is Metaphor | By Steven A. Smith 7 Where the Monitor Is Going, Others Will Follow | By Tom Regan 9 To Prepare for the Future, Skip the Present | By Edward Roussel 11 Journalism as a Conversation | By Katie King 13 Digital Natives: Following Their Lead on a Path to a New Journalism | By Ronald A. Yaros 16 Serendipity, Echo Chambers, and the Front Page | By Ethan Zuckerman Grabbing Readers’ Attention—Youthful Perspectives 18 Net Geners Relate to News in New Ways | By Don Tapscott 20 Passion Replaces the Dullness of an Overused Journalistic Formula | By Robert Niles 21 Accepting the Challenge: Using the Web to Help Newspapers Survive | By Luke Morris 23 Journalism and Citizenship: Making the Connection | By David T.Z. Mindich 26 Distracted: The New News World and the Fate of Attention | By Maggie Jackson 28 Tracking Behavior Changes on the Web | By David Nicholas 30 What Young People Don’t Like About the Web—And News On It | By Vivian Vahlberg 32 Adding Young Voices to the Mix of Newsroom Advisors | By Steven A. Smith 35 Using E-Readers to Explore Some New Media Myths | By Roger Fidler Blogs, Wikis, Social Media—And Journalism 37 Mapping the Blogosphere: Offering a Guide to Journalism’s Future | By John Kelly 40 The End of Journalism as Usual | By Mark Briggs 42 The Wikification of Knowledge | By Kenneth S. -

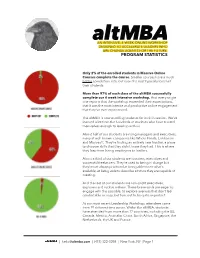

Program Statistics

AN INTENSIVE, 4-WEEK ONLINE WORKSHOP DESIGNED TO ACCELERATE LEADERS WHO ARE CHANGE AGENTS FOR THE FUTURE. PROGRAM STATISTICS Only 2% of the enrolled students in Massive Online Courses complete the course. Smaller courses have a much better completion rate, but even the best typically lose half their students. More than 97% of each class of the altMBA successfully complete our 4 week intensive workshop. And every single one reports that the workshop exceeded their expectations, that it was the most intense and productive online engagement that they’ve ever experienced. The altMBA is now enrolling students for its fifth session. We’ve learned a lot from the hundreds of students who have trusted themselves enough to level up with us. About half of our students are rising managers and executives, many at well-known companies like Whole Foods, Lululemon and Microsoft. They’re finding an entirely new frontier, a place to discover skills that they didn’t know they had. This is where they leap from being employees to leaders. About a third of our students are founders, executives and successful freelancers. They’re used to being in charge but they’re not always practiced at being able to see what’s available, at being able to describe a future they are capable of creating. And the rest of our students are non-profit executives, explorers and ruckus makers. These brave souls are eager to engage with the possible, to explore avenues that don’t feel comfortable or easy, but turn out to be quite important. At our most recent Leadership Workshop, attendees came from 19 different time zones. -

Crowdsourcing Metadata for Library and Museum Collections Using a Taxonomy of Flickr User Behavior

CROWDSOURCING METADATA FOR LIBRARY AND MUSEUM COLLECTIONS USING A TAXONOMY OF FLICKR USER BEHAVIOR A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science by Evan Fay Earle January 2014 © 2014 Evan Fay Earle ABSTRACT Library and museum staff members are faced with having to create descriptions for large numbers of items found within collections. Immense collections and a shortage of staff time prevent the description of collections using metadata at the item level. Large collections of photographs may contain great scholarly and research value, but this information may only be found if items are described in detail. Without detailed descriptions, the items are much harder to find using standard web search techniques, which have become the norm for searching library and museum collection catalogs. To assist with metadata creation, institutions can attempt to reach out to the public and crowdsource descriptions. An example of crowdsourced description generation is the website, Flickr, where the entire user community can comment and add metadata information in the forms of tags to other users’ images. This paper discusses some of the problems with metadata creation and provides insight on ways in which crowdsourcing can benefit institutions. Through an analysis of tags and comments found on Flickr, behaviors are categorized to show a taxonomy of users. This information is used in conjunction with survey data in an effort to show if certain types of users have characteristics that are most beneficial to enhancing metadata in existing library and museum collections. -

Litigation, Legislation, and Democracy in a Post- Newspaper America

SJ Quinney College of Law, University of Utah Utah Law Digital Commons Utah Law Faculty Scholarship Utah Law Scholarship 2011 Litigation, Legislation, and Democracy in a Post- Newspaper America RonNell Anderson Jones Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.law.utah.edu/scholarship Washington and Lee Law Review Volume 68 | Issue 2 Article 3 3-1-2011 Litigation, Legislation, and Democracy in a Post- Newspaper America RonNell Anderson Jones Recommended Citation RonNell Anderson Jones, Litigation, Legislation, and Democracy in a Post-Newspaper America, 68 Wash. & Lee L. Rev. 557 (2011), http://scholarlycommons.law.wlu.edu/wlulr/vol68/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Washington & Lee University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington and Lee Law Review by an authorized administrator of Washington & Lee University School of Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Litigation, Legislation, and Democracy in a Post-Newspaper America RonNell Andersen Jones* Table of Contents I. Introduction .................................................................................. 558 II. Dying Newspapers and the Loss of Legal Instigation and Enforcement .......................................................................... 562 A. The Decline of the American Newspaper ............................. 562 B. The Unrecognized Threat to Democracy .............................. 570 1. Important Constitutional Developments ........................ -

Making It Pay to Be a Fan: the Political Economy of Digital Sports Fandom and the Sports Media Industry

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2018 Making It Pay to be a Fan: The Political Economy of Digital Sports Fandom and the Sports Media Industry Andrew McKinney The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2800 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] MAKING IT PAY TO BE A FAN: THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF DIGITAL SPORTS FANDOM AND THE SPORTS MEDIA INDUSTRY by Andrew G McKinney A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Sociology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2018 ©2018 ANDREW G MCKINNEY All Rights Reserved ii Making it Pay to be a Fan: The Political Economy of Digital Sport Fandom and the Sports Media Industry by Andrew G McKinney This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Sociology in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date William Kornblum Chair of Examining Committee Date Lynn Chancer Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: William Kornblum Stanley Aronowitz Lynn Chancer THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK I iii ABSTRACT Making it Pay to be a Fan: The Political Economy of Digital Sport Fandom and the Sports Media Industry by Andrew G McKinney Advisor: William Kornblum This dissertation is a series of case studies and sociological examinations of the role that the sports media industry and mediated sport fandom plays in the political economy of the Internet. -

A Socio-Rhetorical Analysis of Sports-Tagged Content Produced by Youtubers

A Socio-Rhetorical Analysis of Sports-Tagged Content Produced by Youtubers Roselis N. Mazzuchetti;Vinicios Mazzuchetti;Adalberto Dias de Souza;Ismael Barbosa Abstract This research proposes a socio-rhetorical analysis of videos posted on YouTube under the tag “Sports”, specifically the regular content created by users, so-called YouTubers. The theoretical basis contemplates the concept of technology – based on the works by Viera Pinto (2005) – and participatory cultured – mainly guided by ideas from Shirky (2008, 2011). The analytical device is derived from work by Swales (1990, 1998, 2004), Askehave & Swales (2001), and Miller (1998, 2012). A hybrid methodology was created, resulting from the sociological and linguistic concepts applied to the organizational reality of virtual massive communication. The analysis decomposes the video in rhetorical movements. We follow the hypothesis that the main purpose of such communicational practices is self-promotion of the individual who produce the YouTube channel, or the promotion of the brand of which constitutes the channel produced by multiple users. Furthermore, the self- promotion and widening of audience is pursued with financial purpose. Keyword: Technology. Sports. Socio-rhetorical analysis. Published Date: 7/31/2019 Page.78-92 Vol 7 No 7 2019 DOI: https://doi.org/10.31686/ijier.Vol7.Iss7.1576 International Journal of Innovation Education and Research www.ijier.net Vol:-7 No-7, 2019 A Socio-Rhetorical Analysis of Sports-Tagged Content Produced by Youtubers Roselis N. Mazzuchetti Dept. of Engineering, Universidade Estadual do Paraná – UNESPAR Paranaguá, Paraná, Brazil Vinicios Mazzuchetti Dept. de Education, Universidade Tecnológica Federal do Paraná - UTFPR Adalberto Dias de Souza Universidade Estadual do Paraná – UNESPAR Ismael Barbosa Universidade Estadual do Paraná - UNESPAR ABSTRACT This research proposes a socio-rhetorical analysis of videos posted on YouTube under the tag “Sports”, specifically the regular content created by users, so-called YouTubers. -

Networked Activism

\\server05\productn\H\HLH\22-2\HLH208.txt unknown Seq: 1 25-AUG-09 8:28 Networked Activism Molly Beutz Land* The same technologies that groups of ordinary citizens are using to write operating systems and encyclopedias are fostering a quiet revolution in an- other area—social activism. On websites such as Avaaz.org and Wikipedia, citizens are forming groups to report on human rights violations and organ- ize email writing campaigns, activities formerly the prerogative of profes- sionals. Because the demands of human rights work often require organizations to professionalize in order to be successful in their advocacy, human rights provides an ideal case study for evaluating the effect of low- ered barriers to online group formation on citizen participation in activism. This article considers whether the participatory potential of technology can be used to both broaden the mobilization of ordinary citizens in human rights advocacy and provide opportunities for individuals to become more deeply involved in the work. Existing online advocacy efforts reveal a de facto inverse relationship be- tween broad mobilization and deep participation. Large groups mobilize many individuals, but each of those individuals has only a limited ability to participate in decisions about the group’s goals or methods. This inverse relationship is principally a problem of size. As groups grow in size, they may replicate the process of professionalization in order to avoid the problems that would be associated with decentralized decision-making. Thus, although we currently have the tools necessary for individuals to en- gage in advocacy without the need for professional organizations, we are still far from realizing an ideal of fully decentralized, user-generated activism. -

Social Media Impacts on Social & Political Goods: a Peacebuilding Perspective

Policy Brief No. 20 APLN/CNND 1 Policy Brief #22 October 2018 Social Media Impacts on Social & Political Goods: A Peacebuilding Perspective Lisa Schirch The Toda Peace Institute and the Alliance for Peacebuilding are hosting a series of policy briefs discussing social media impacts on social and political goods. Over the next several months, top experts and thought leaders will provide insight into social media’s threats and opportunities. This first briefing provides a conceptual summary, and a set of policy recommendations to address the significant threats to social and political goods. The Full Report provides a more in-depth literature review and explanation of key themes. ABSTRACT Social media is both an asset and a threat to social and political goods. This first in a series of policy briefs on social media aims to build the capacity of civil society to un- derstand the economic and psychological appeal of social media, identify the range of opportunities and challenges related to social media, and promote discussion on po- tential solutions to these challenges. Currently, few in civil society or government un- derstand how social media works. Technology experts and investor-oriented social media platforms cannot address the opportunities and challenges brought by social media capabilities. Together, government, corporations, and civil society, need to find ways to respond to the growing crisis of social media ethics and impacts. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY • All forms of media hold the potential for both solving and amplifying so- cial and political problems. Media is, as its Latin root suggests, “in the mid- dle”; it is a channel for communication between people. -

A Shared Digital Future? Will the Possibilities for Mass Creativity on the Internet Be Realized Or Squandered, Asks Tony Hey

NATURE|Vol 455|4 September 2008 OPINION A shared digital future? Will the possibilities for mass creativity on the Internet be realized or squandered, asks Tony Hey. The potential of the Internet and the attack, such as that dramatized in web for creating a better, more inno- the 2007 movie Live Free or Die vative and collaborative future is Hard (also titled Die Hard 4.0). discussed in three books. Together, Zittrain argues that security they make a convincing case that problems could lead to the ‘appli- we are in the midst of a revolution ancization’ of the Internet, a return as significant as that brought about to managed interfaces and a trend by Johannes Gutenberg’s invention towards tethered devices, such as of movable type. Sharing many the iPhone and Blackberry, which WATTENBERG VIÉGAS/M. BERTINI F. examples, notably Wikipedia and are subject to centralized control Linux, the books highlight different and are much less open to user concerns and opportunities. innovation. He also argues that The Future of the Internet the shared technologies that make addresses the legal issues and dan- up Web 2.0, which are reliant on gers involved in regulating the Inter- remote services offered by commer- net and the web. Jonathan Zittrain, cial organizations, may reduce the professor of Internet governance user’s freedom for innovation. I am and regulation at the Univ ersity of unconvinced that these technologies Oxford, UK, defends the ability of will kill generativity: smart phones the Internet and the personal com- are just computers, and specialized puter to produce “unanticipated services, such as the image-hosting change through unfiltered con- An editing history of the Wikipedia entry on abortion shows the numerous application SmugMug, can be built tributions from broad and varied contributors (in different colours) and changes in text length (depth). -

A Group Is Its Own Worst Enemy 1

Clay Shirky A GROUP IS ITS OWN WORST ENEMY 1 In the late 1980s, software went through a major transition. Before about 1985, the primary goal of software was making it possible to solve a problem, by any means necessary. Do you need to punch cards with your input data? No big deal. A typo on one card means you have to throw it away and start over? No problem. Humans will bend to the machines, like Charlie Chaplin in Modern Times. Suddenly with personal computers the bar was raised. It wasn’t enough just to solve the problem: you had to solve it easily, in a way that takes into account typical human frailties. The backspace key, for example, to compensate for human frailty, not to mention menus, icons, windows, and unlimited Undo. And we called this usability, and it was good. Lo and behold, when the software industry tried to hire experts in usability, they found that it was a new field, so nobody was doing this. There was this niche field in psychiatry called ergonom- ics, but it was mostly focused on things from the physical world, like finding the optimal height for a desk chair. Eventually usability came into its own as a first-class field of study, with self-trained practitioners and university courses, and no software project could be considered complete without at least a cursory glance at usability. 1. This is a lightly edited version of the keynote Clay Shirky gave on social software at the O’Reilly Emerging Technology conference in Santa Clara on April 24, 2003. -

The Rise of Twitter Fiction…………………………………………………………1

Twitter Fiction: A Shift in Author Function Hilary Hyman Twitter fiction, an example of twenty-first century digital narrative, allows authors to experiment with literary form, production, and dissemination as they engage readers through a communal network. Twitter offers creative space for both professionals and amateurs to publish fiction digitally, enabling greater collaboration among authors and readers. Examining Jennifer Egan’s “Black Box” and selected Twitter stories from Junot Diaz, Teju Cole, and Elliott Holt, this thesis establishes two distinct types of Twitter fiction—one produced for the medium and one produced through it—to consider how Twitter’s present feed and character limit fosters a uniquely interactive reading experience. As the conversational medium calls for present engagement with the text and with the author, Twitter promotes newly elastic relationships between author and reader that renegotiate the former boundaries between professionals and amateurs. This thesis thus considers how works of Twitter fiction transform the traditional author function and pose new questions regarding digital narrative’s modes of existence, circulation, and appropriation. As digital narrative makes its way onto democratic forums, a shifted author function leaves us wondering what it means to be an author in the digital age. Twitter Fiction: A Shift in Author Function Hilary Anne Hyman Twitter Fiction: A Shift in Author Function Hilary Anne Hyman An Undergraduate Honors Thesis Submitted to the Department of English at Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in the Major April 18, 2016 Thesis Adviser: Vera Kutzinski Date Second Reader: Haerin Shin Date Program Director: Teresa Goddu Date For My Parents Acknowledgements I would like to acknowledge Professor Teresa Goddu for shaping me into the writer I have become.