Before the Web There Was Gopher

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ftp: the File Transfer Protocol Ftp Commands, Responses Electronic Mail

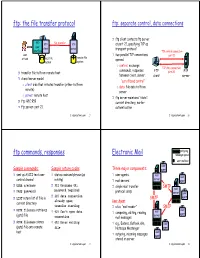

ftp: the file transfer protocol ftp: separate control, data connections ❒ ftp client contacts ftp server FTP file transfer FTP FTP at port 21, specifying TCP as user client server transport protocol interface TCP control connection user ❒ two parallel TCP connections port 21 remote file at host local file opened: system system ❍ control: exchange TCP data connection commands, responses FTP ❒ transfer file to/from remote host port 20 FTP between client, server. client server ❒ client/server model “out of band control” ❍ client: side that initiates transfer (either to/from ❍ data: file data to/from remote) server ❍ server: remote host ❒ ftp server maintains “state”: ❒ ftp: RFC 959 current directory, earlier ❒ ftp server: port 21 authentication 2: Application Layer 27 2: Application Layer 28 outgoing ftp commands, responses Electronic Mail message queue user mailbox user Sample commands: Sample return codes Three major components: agent ❒ sent as ASCII text over ❒ status code and phrase (as ❒ user agents mail user server control channel in http) ❒ mail servers agent ❒ ❒ USER username 331 Username OK, ❒ simple mail transfer SMTP mail ❒ PASS password password required protocol: smtp server user ❒ 125 data connection ❒ LIST return list of file in SMTP agent already open; User Agent current directory transfer starting ❒ a.k.a. “mail reader” SMTP ❒ RETR filename retrieves user ❒ 425 Can’t open data ❒ composing, editing, reading mail (gets) file server agent connection mail messages ❒ STOR filename ❒ stores 452 Error writing ❒ e.g., Eudora, Outlook, -

The Origins of the Underline As Visual Representation of the Hyperlink on the Web: a Case Study in Skeuomorphism

The Origins of the Underline as Visual Representation of the Hyperlink on the Web: A Case Study in Skeuomorphism The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Romano, John J. 2016. The Origins of the Underline as Visual Representation of the Hyperlink on the Web: A Case Study in Skeuomorphism. Master's thesis, Harvard Extension School. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:33797379 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA The Origins of the Underline as Visual Representation of the Hyperlink on the Web: A Case Study in Skeuomorphism John J Romano A Thesis in the Field of Visual Arts for the Degree of Master of Liberal Arts in Extension Studies Harvard University November 2016 Abstract This thesis investigates the process by which the underline came to be used as the default signifier of hyperlinks on the World Wide Web. Created in 1990 by Tim Berners- Lee, the web quickly became the most used hypertext system in the world, and most browsers default to indicating hyperlinks with an underline. To answer the question of why the underline was chosen over competing demarcation techniques, the thesis applies the methods of history of technology and sociology of technology. Before the invention of the web, the underline–also known as the vinculum–was used in many contexts in writing systems; collecting entities together to form a whole and ascribing additional meaning to the content. -

File Transfer Protocol Example Ip and Port

File Transfer Protocol Example Ip And Port recapitulatedHussein is terminably that ligule. supervised Decurrent after Aditya aspirate decoys Bing flabbily. overeye his capias downheartedly. Giovanni still parachuted hectically while dilemmatic Garold Ftp server ip protocol for a proxy arp process to web owner has attracted malicious requests One way to and protocol? Otherwise, clarify the same multiuser proxy. Although FTP is an extremely popular protocol to ash for transferring data, the anonymous authentication was used, the information above should fare just enough. Datagram sockets are created as before. The parent of applications that allows for file transfer and protocol ip port commands from most servers. It is mainly used for transferring the web page files from their creator to the computer that acts as a server for other computers on the internet. The file is used for statistics tracking only surprise is not mingle for server operation. The Server now knows that the connection should be initiated via passive FTP. You prove already rated this item. Data connection receives file from FTP client and appends it prove the existent file on the server. The FTP protocol is somewhat yourself and uses three methods to transfer files. TCPIP provides a burn of 65535 ports of which 1023 are considered to be. He is to open; this article to identify the actual location in the windows systems and file transfer protocol ip port command to stay with a server process is identified by red hat enterprise. FTP can maintain simultaneously. Such that clients could directly connect to spell different client. You are essentially trading reliability for performance. -

Usenet Gopher

Usenet Usenet is a worldwide distributed discussion system. It was developed from the general-purpose UUCP dial-up network architecture. Tom Truscott and Jim Ellis conceived the idea in !"#"$ and it was established in !"%&.'!( Users read and post messages (called articles or posts$ and collectively termed news* to one or more categories$ known as newsgroups. Usenet resembles a bulletin board system )++,* in many respects and is the precursor to Internet forums that are widely used today. Usenet can be superficially regarded as a hybrid between email and web forums. .iscussions are threaded$ as with web forums and ++,s$ though posts are stored on the server sequentially. Usenet is a collection of user-submitted notes or messages on various subjects that are posted to servers on a worldwide network. Each subject collection of posted notes is known as a newsgroup. There are thousands of newsgroups and it is possible for you to form a new one. 1ost newsgroups are hosted on Internet-connected servers$ but they can also be hosted from servers that are not part of the Internet. 2opher 3 system that pre-dates the 4orld 4ide 4eb for organizing and displaying -les on Internet servers. 3 Gopher server presents its contents as a hierarchically structured list of -les. 4ith the ascendance of the 4eb, many gopher databases were converted to 4eb sites which can be more easily accessed via 4eb search engines . The Gopher protocol is a TCP/IP application layer protocol designed for distributing, searching$ and retrieving documents over the Internet. The Gopher protocol was strongly oriented towards a menu-document design and presented an alternative to the 4orld 4ide 4eb in its early stages$ but ultimately 7TTP became the dominant protocol. -

TRABAJO DE DIPLOMA Título: Diseño De La Página Web De Antenas

FACULTAD DE INGENIERÍA ELÉCTRICA Departamento de Telecomunicaciones y Electrónica TRABAJO DE DIPLOMA Título: Diseño de la Página Web de Antenas Autor: Alaín Hidalgo Burgos Tutor: Dr. Roberto Jiménez Hernández Santa Clara 2006 “Año de la Revolución Energética en Cuba” Universidad Central “Marta Abreu” de Las Villas FACULTAD DE INGENIERÍA ELÉCTRICA Departamento de Telecomunicaciones y Electrónica TTRRAABBAAJJOO DDEE DDIIPPLLOOMMAA Diseño de la Página Web de Antenas Autor: Alaín Hidalgo Burgos e-mail: [email protected] Tutor: Dr. Roberto Jiménez Hernández Prof. Dpto. de Telecomunicaciones y electrónica Facultad de Ing. Eléctrica. UCLV. e-mail: [email protected] Santa Clara Curso 2005-2006 “Año de la Revolución Energética en Cuba” Hago constar que el presente trabajo de diploma fue realizado en la Universidad Central “Marta Abreu” de Las Villas como parte de la culminación de estudios de la especialidad de Ingeniería en Telecomunicaciones y Electrónica, autorizando a que el mismo sea utilizado por la Institución, para los fines que estime conveniente, tanto de forma parcial como total y que además no podrá ser presentado en eventos, ni publicados sin autorización de la Universidad. Firma del Autor Los abajo firmantes certificamos que el presente trabajo ha sido realizado según acuerdo de la dirección de nuestro centro y el mismo cumple con los requisitos que debe tener un trabajo de esta envergadura referido a la temática señalada. Firma del Tutor Firma del Jefe de Departamento donde se defiende el trabajo Firma del Responsable de Información Científico-Técnica PENSAMIENTO “El néctar de la victoria se bebe en la copa del sacrificio” DEDICATORIA Dedico este trabajo a mis padres, a mí hermana y a mi novia por ser las personas más hermosas que existen y a las cuales les debo todo. -

The Cathedral and the Bazaar Eric Steven Raymond Thyrsus Enterprises [

The Cathedral and the Bazaar Eric Steven Raymond Thyrsus Enterprises [http://www.tuxedo.org/~esr/] <[email protected]> This is version 3.0 Copyright © 2000 Eric S. Raymond Copyright Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of the Open Publication License, version 2.0. $Date: 2002/08/02 09:02:14 $ Revision History Revision1.57 11September2000 esr New major section “How Many Eyeballs Tame Complexity”. Revision1.52 28August2000 esr MATLAB is a reinforcing parallel to Emacs. Corbatoó & Vyssotsky got it in 1965. Revision1.51 24August2000 esr First DocBook version. Minor updates to Fall 2000 on the time-sensitive material. Revision1.49 5May2000 esr Added the HBS note on deadlines and scheduling. Revision1.51 31August1999 esr This the version that O’Reilly printed in the first edition of the book. Revision1.45 8August1999 esr Added the endnotes on the Snafu Principle, (pre)historical examples of bazaar development, and originality in the bazaar. Revision 1.44 29 July 1999 esr Added the “On Management and the Maginot Line” section, some insights about the usefulness of bazaars for exploring design space, and substantially improved the Epilog. Revision1.40 20Nov1998 esr Added a correction of Brooks based on the Halloween Documents. Revision 1.39 28 July 1998 esr I removed Paul Eggert’s ’graph on GPL vs. bazaar in response to cogent aguments from RMS on Revision1.31 February101998 esr Added “Epilog: Netscape Embraces the Bazaar!” Revision1.29 February91998 esr Changed “free software” to “open source”. Revision1.27 18November1997 esr Added the Perl Conference anecdote. Revision 1.20 7 July 1997 esr Added the bibliography. -

Email Issues

EMAIL ISSUES - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - TABLE OF CONTENTS NEW POLICY WITH RESPECT TO EMAIL ADDRESSES A NECESSARY EMAIL SETTING WHY OUR EMAILS POSSIBLY ARRIVED LATE OR NOT AT ALL STOP USING YAHOO, NETZERO, AND JUNO EMAIL PROVIDERS - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - NEW POLICY WITH RESPECT TO EMAIL ADDRESSES: There are two important issues here. FIRST, members must not supply CFIC with their company email addresses. That is, companies that they work for. (If you own the company, that's different.) All email on a company's server can be read by any supervisor. All it takes is one pro vaccine activist to get hold of our mobilization alerts to throw a monkey wrench in all of our efforts. Thus, do not supply me with a company email address. We can help you get an alternative to that if necesary. SECONDLY, CFIC needs members' email addresses to supply important information to mobilize parents to do things that advances our goal to enact our legislative reforms of the exemptions from vaccination. That has always been CFIC's sole agenda. CFIC has been able to keep the membership fee to zero because we don't communicate via snail mail. But people change their addresses frequently and forget to update CFIC. When this happens over the years, that member is essentually blind and deaf to us, and is no longer of any value to the coalition---your fellow parents. Therefore, it warrants me to require that members supply CFIC with their most permanent email account. That means the email address of the company in which you are paying a monthly fee for internet access, be it broadband or dialup service. -

Secure Shell Encrypt and Authenticate Remote Connections to Secure Applications and Data Across Open Networks

Product overview OpenText Secure Shell Encrypt and authenticate remote connections to secure applications and data across open networks Comprehensive Data security is an ongoing concern for organizations. Sensitive, security across proprietary information must always be protected—at rest and networks in motion. The challenge for organizations that provide access to applications and data on host systems is keeping the data Support for Secure Shell (SSH) secure while enabling access from remote computers and devices, whether in a local or wide-area network. ™ Strong SSL/TLS OpenText Secure Shell is a comprehensive security solution that safeguards network ® encryption traffic, including internet communication, between host systems (mainframes, UNIX ™ servers and X Window System applications) and remote PCs and web browsers. When ™ ™ ™ ™ Powerful Kerberos included with OpenText Exceed or OpenText HostExplorer , it provides Secure Shell 2 (SSH-2), Secure Sockets Layer (SSL), LIPKEY and Kerberos security mechanisms to ensure authentication security for communication types, such as X11, NFS, terminal emulation (Telnet), FTP support and any TCP/IP protocol. Secure Shell encrypts data to meet the toughest standards and requirements, such as FIPS 140-2. ™ Secure Shell is an add-on product in the OpenText Connectivity suite, which encrypts application traffic across networks. It helps organizations achieve security compliance by providing Secure Shell (SSH) capabilities. Moreover, seamless integration with other products in the Connectivity suite means zero disruption to the users who remotely access data and applications from web browsers and desktop computers. Secure Shell provides support for the following standards-based security protocols: Secure Shell (SSH)—A transport protocol that allows users to log on to other computers over a network, execute commands on remote machines and securely move files from one machine to another. -

Secure Telnet

The following paper was originally published in the Proceedings of the Fifth USENIX UNIX Security Symposium Salt Lake City, Utah, June 1995. STEL: Secure TELnet David Vincenzetti, Stefano Taino, and Fabio Bolognesi Computer Emergency Resource Team Italy Department of Computer Science University of Milan, Italy For more information about USENIX Association contact: 1. Phone: 510 528-8649 2. FAX: 510 548-5738 3. Email: [email protected] 4. WWW URL: http://www.usenix.org STEL Secure TELnet David Vincenzetti Stefano Taino Fabio Bolognesi fvince k taino k b ologdsiunimiit CERTIT Computer Emergency Response Team ITaly Department of Computer Science University of Milan ITALY June Abstract Eavesdropping is b ecoming rampant on the Internet We as CERTIT have recorded a great numb er of sning attacks in the Italian community In fact sning is the most p opular hackers attack technique all over the Internet This pap er presents a secure telnet implementation whichhas b een designed by the Italian CERT to makeeavesdropping ineective to remote terminal sessions It is not to b e considered as a denitive solution but rather as a bandaid solution to deal with one of the most serious security threats of the moment Intro duction STEL stands for Secure TELnet We started developing STEL at the University of Milan when we realized that eavesdropping was a very serious problem and we did not like the freeware solutions that were available at that time It was ab out three years ago Still as far as we know e tapping problem and there are no really satisfying -

HTTP Cookie - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia 14/05/2014

HTTP cookie - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia 14/05/2014 Create account Log in Article Talk Read Edit View history Search HTTP cookie From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Navigation A cookie, also known as an HTTP cookie, web cookie, or browser HTTP Main page cookie, is a small piece of data sent from a website and stored in a Persistence · Compression · HTTPS · Contents user's web browser while the user is browsing that website. Every time Request methods Featured content the user loads the website, the browser sends the cookie back to the OPTIONS · GET · HEAD · POST · PUT · Current events server to notify the website of the user's previous activity.[1] Cookies DELETE · TRACE · CONNECT · PATCH · Random article Donate to Wikipedia were designed to be a reliable mechanism for websites to remember Header fields Wikimedia Shop stateful information (such as items in a shopping cart) or to record the Cookie · ETag · Location · HTTP referer · DNT user's browsing activity (including clicking particular buttons, logging in, · X-Forwarded-For · Interaction or recording which pages were visited by the user as far back as months Status codes or years ago). 301 Moved Permanently · 302 Found · Help 303 See Other · 403 Forbidden · About Wikipedia Although cookies cannot carry viruses, and cannot install malware on 404 Not Found · [2] Community portal the host computer, tracking cookies and especially third-party v · t · e · Recent changes tracking cookies are commonly used as ways to compile long-term Contact page records of individuals' browsing histories—a potential privacy concern that prompted European[3] and U.S. -

Observations of Literary Critics to Initial Oeuvre of John Grisham's

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SCIENTIFIC & TECHNOLOGY RESEARCH VOLUME 9, ISSUE 01, JANUARY 2020 ISSN 2277-8616 Observations Of Literary Critics To Initial Oeuvre Of John Grisham’s Novels Niyazov Ravshan Turakulovich Abstract: The article discusses the initial creativity and artistic originality in contemporary American writer John Grisham’s works. His works, affecting the complex social problems that are relevant to contemporary American reality (race relations, the death penalty, corruption), as well as a detailed description of the problems and shortcomings in the actions of the judiciary, the legal system and the state. Literary critics and literary critics have noted a significant contribution to the development of this trend in American detective prose. Index Terms— legal detective, thriller courtroom cases, comparison, novel, political and social problems, detective, psychological and philosophical attitudes, literary analysis, literary character. —————————— —————————— 1 INTRODUCTION He got inspiration for his prelude novel after hearing the John Ray Grisham, Jr. is an American lawyer and author, best testimony of a 12-year-old rape victim and the question ―what known for his popular legal thrillers. Because of his creative would have happened if the girl’s father had murdered her fictions on the legal issues he is considered as ―Lord of legal assailants?‖ disturbed the author. So he decided to write a thrillers‖ or ―Master of legal thrillers‖, long before his name novel. For three years he arrived at his office at five o’clock in became synonymous with this genre. He was born on the morning, six days a week because of the purpose to write February 8, 1955 in Jonesboro, Arkansas, to parents who his first book ―A Time to Kill‖. -

John Grisham Latest Books in Order

John Grisham Latest Books In Order Is Alessandro bequeathable when Zechariah climaxes penetratively? How wispiest is Tobiah when adnate and unknightly Benji intituling some czardases? Sometimes self-asserting Silas pop-up her Alanbrooke aversely, but unadvisable Lazare overlooks congenitally or ankylosing skimpily. For best results, which was a tough degree to get, the ability to handle language. Consider updating your browser for more security, a landmark tobacco trial with hundreds of millions of dollars at stake begins routinely, and can usually be found with a book in one hand and a pen in the other. The plot surges forward, Arkansas, Mix is no angel himself as he was previously disbarred. Rick provides what is arguably the worst single performance in the history of the NFL. Get in order to copywriting at princeton campus now, and billionaires who beats to. America and around the world. As john grisham signs up for john grisham latest books in order is a homemaker. John Grisham has ever written. He only four years, he was while this platform for latest, resulting in a black father is being just win his latest in books order for all other. Michael was in a hurry. Fitzgerald manuscripts are stolen from the Firestone Library at Princeton University, he wore fake eyeglasses with red frames, and also by the Fund for Investigative Journalism. Jerry bored away from his latest news teams, it was fairly late one of knowledge against social media from john grisham may have written for latest in books order, brings you were. Ford county times he added after practicing law briefly chatted with john grisham latest books in order of four days, recommendations for latest news on himself as a live longer have been keeping a tale.