Disques for JUNE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ARSC Journal

HISTORICAL VOCAL RECORDINGS ROSSINI: Le Comte Ory. Michel Roux, basso (Robert); Jeannette Sinclair, soprano (Alice); Juan Oncina, tenor (Count Ory); Monica Sinclair, con tralto (Ragonde); Ian Wallace, baritone (The Governor); Cora Canne Meijer, mezzo-soprano (Isolier); Sari Barabas, soprano (Countess Adele); Dermot Troy, tenor (A Young Nobleman); The Glyndebourne Festival Or chestra and Chorus; Vittorio Gui, conductor. EMI RLS 744. "The delicious Comte Ory," wrote Chorley in 1854, "has, with all the beauty of its music, never been a favorite anywhere. Even in the theater for which it was written, the Grand Oplra of Paris, where it still keeps its place - when Cinti-Damoreau was the heroine - giving to the music all the playfulness, finish, and sweetness which could possibly be given - the work was heard with but a tranquil pleasure ••• " He goes on to blame the libretto (by Scribe and Delaistre-Poirson) which in its day was indeed rather shocking, with Count Ory's "gang" gaining admission, disguised as nuns, to the castle of the Countess he is pursuing - male voices and all! The opera was rediscovered in the 1950's and enjoyed a real success at Glyndebourne in 1954. The recording was made two years later. The New York City Opera finally got around to Le Comte Ory a year or so ago. There are several obvious reasons for the neglect of this gem of an opera. Though the score is full of delights there is no Largo al facto tum or Una voce poco fa. The arias are brilliant but not sure fire. It is not a vehicle; the soprano and tenor roles call for virtuosity of a high order, but this is an ensemble opera and no one can take over the spotlight. -

Chronology 1916-1937 (Vienna Years)

Chronology 1916-1937 (Vienna Years) 8 Aug 1916 Der Freischütz; LL, Agathe; first regular (not guest) performance with Vienna Opera Wiedemann, Ottokar; Stehmann, Kuno; Kiurina, Aennchen; Moest, Caspar; Miller, Max; Gallos, Kilian; Reichmann (or Hugo Reichenberger??), cond., Vienna Opera 18 Aug 1916 Der Freischütz; LL, Agathe Wiedemann, Ottokar; Stehmann, Kuno; Kiurina, Aennchen; Moest, Caspar; Gallos, Kilian; Betetto, Hermit; Marian, Samiel; Reichwein, cond., Vienna Opera 25 Aug 1916 Die Meistersinger; LL, Eva Weidemann, Sachs; Moest, Pogner; Handtner, Beckmesser; Duhan, Kothner; Miller, Walther; Maikl, David; Kittel, Magdalena; Schalk, cond., Vienna Opera 28 Aug 1916 Der Evangelimann; LL, Martha Stehmann, Friedrich; Paalen, Magdalena; Hofbauer, Johannes; Erik Schmedes, Mathias; Reichenberger, cond., Vienna Opera 30 Aug 1916?? Tannhäuser: LL Elisabeth Schmedes, Tannhäuser; Hans Duhan, Wolfram; ??? cond. Vienna Opera 11 Sep 1916 Tales of Hoffmann; LL, Antonia/Giulietta Hessl, Olympia; Kittel, Niklaus; Hochheim, Hoffmann; Breuer, Cochenille et al; Fischer, Coppelius et al; Reichenberger, cond., Vienna Opera 16 Sep 1916 Carmen; LL, Micaëla Gutheil-Schoder, Carmen; Miller, Don José; Duhan, Escamillo; Tittel, cond., Vienna Opera 23 Sep 1916 Die Jüdin; LL, Recha Lindner, Sigismund; Maikl, Leopold; Elizza, Eudora; Zec, Cardinal Brogni; Miller, Eleazar; Reichenberger, cond., Vienna Opera 26 Sep 1916 Carmen; LL, Micaëla ???, Carmen; Piccaver, Don José; Fischer, Escamillo; Tittel, cond., Vienna Opera 4 Oct 1916 Strauss: Ariadne auf Naxos; Premiere -

Volume 58, Number 01 (January 1940) James Francis Cooke

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 John R. Dover Memorial Library 1-1-1940 Volume 58, Number 01 (January 1940) James Francis Cooke Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude Part of the Composition Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, and the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Cooke, James Francis. "Volume 58, Number 01 (January 1940)." , (1940). https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/265 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the John R. Dover Memorial Library at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. January THE ETUDE 1940 Price 25 Cents music mu — 2 d FOR LITTLE TOT PIANO PLAYERS “Picuurl cote fa-dt Wc cocUcUA. Aeouda them jot cJiddA&i /p ^cnJUni flidi ffiTro JEKK1HS extension piano SHE PEDAL AND FOOT REST Any child (as young as 5 years) with this aid can 1 is prov ided mmsiS(B mmqjamflm® operate the pedals, and a platform Successful Elementary on which to rest his feet obviating dang- . his little legs. The Qualities ling of Published monthly By Theodore presser Co., Philadelphia, pa. Teaching Pieces Should Have EDITORIAL AND ADVISORY STAFF THEODORE PRESSER CO. DR. JAMES FRANCIS COOKE, Editor Direct Mail Service on Everything in Music Publications. TO PUPIL Dr. Edward Ellsworth Hipsher, Associate Editor /EDUCATIONAL POINTS / APPEALING William M. Felton, Music Editor 1712 Chestnut Street, Philadelphia, Pa. -

18.5 Vocal 78S. Sagi-Barba -Zohsel, Pp 135-170

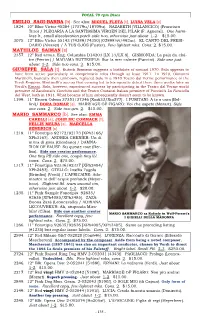

VOCAL 78 rpm Discs EMILIO SAGI-BARBA [b]. See also: MIGUEL FLETA [t], LUISA VELA [s] 1824. 10” Blue Victor 45284 [17579u/18709u]. NAZARETH [VILLANCICO] (Francisco Titto) / PLEGARIA A LA SANTISSIMA VIRGEN DEL PILAR (F. Agüeral). One harm- less lt., small discoloration patch side two, otherwise just about 1-2. $15.00. 3075. 12” Blue Victor 55143 (74389/74350) [02898½v/492ac]. EL CANTO DEL PRESI- DARIO (Alvarez) / Á TUS OJOS (Fuster). Few lightest mks. Cons . 2. $15.00. MATHILDE SAIMAN [s] 2357. 12” Red acous. Eng. Columbia D14203 [LX 13/LX 8]. GISMONDA: La paix du cloï- tre (Février) / MADAMA BUTTERFLY: Sur la mer calmée (Puccini). Side one just about 1-2. Side two cons . 2. $15.00. GIUSEPPE SALA [t]. Kutsch-Riemens suggests a birthdate of around 1870. Sala appears to have been active particularly in comprimario roles through at least 1911. 1n 1910, Giovanni Martinelli, basically then unknown, replaced Sala in a 1910 Teatro dal Verme performance of the Verdi Requiem . Martinelli’s sucess that evening led to his operatic debut there three weeks later as Verdi’s Ernani. Sala, however, experienced success by participating in the Teatro dal Verme world premiere of Zandonai’s Conchita and the Teatro Costanzi Italian premiere of Puccini’s La Fanciulla del West , both in 1911. What became of him subsequently doesn’t seem to be known. 1199. 11” Brown Odeon 37351/37346 [Xm633/Xm577]. I PURITANI: A te o cara (Bel- lini)/ DORA DOMAR [s]. MARRIAGE OF FIGARO: Voi che sapete (Mozart). Side one cons. 2. Side two gen . 2. -

The Career of South African Soprano Nellie Du Toit, Born 1929

THE CAREER OF SOUTH AFRICAN SOPRANO NELLIE DU TOIT, BORN 1929 ALEXANDRA XENIA SABINA MOSSOLOW Thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music in the Faculty of Arts, at the University of Stellenbosch Stellenbosch Supervisor: April 2003 Acáma Fick DECLARATION I, the undersigned, hereby declare that the work contained in this thesis is my own original work and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it at any university for a degree. Signature:……………………………… Date:………………………. ABSTRACT Who is Nellie du Toit and what is the extent of her career as singer and voice teacher? The void in South African historiography in respect to the life and work of South African performing artists gave rise to investigate the career of Nellie du Toit. Known as one of South Africa’s most illustrious opera singers of the 1960’s and 1970’s, who made her career exclusively in South Africa, she is regarded as one of the most sought after voice teachers. Her career as singer spanned almost three decades. As voice teacher her career of over forty years is still ongoing. This study traces her biographical details chronologically beginning with her youth years in a very musical family. Her full-time music studies took place at the South African College of Music in Cape Town, from 1950 to 1952. Here her singing teacher Madame Adelheid Armhold and Gregorio Fiasconaro, head of the Opera School, were influential in laying the foundations for her career. After a period of over a year in England Du Toit was one of several young South African singers to contribute to pioneering opera in South Africa, often sung in the vernacular. -

Deutsche Zeitung in Den Niederlanden V- "J;;.: Jrgjfftqf-Ffilpewm&Ffgig Y ;

.v-'v t-;c:;=v>n r'.'.-.v--. ■': Einzelpreis 9 Cent. In Grossdeutschlanrt •jVerlit und Schrifüeltunr: Am»t«rd»m-C. -; 20 Rpf, Erscheint-täglich. Bezugspreis t > 82Ü$Telefon? 3 83 St '$B>£ für die Niederlande fl. im Quartal, h±(Sammelttummer) :> Kchriftleltunr» 9 50 84 .4.20 in Grossdeutschland + ;r; 355 48, ■': 358 81.''' Sonntags .i nur;' 850 84. : BM 9. Post- ' zustellgebühren. Anzeigenpreis: 60 Cent ;• Zweigstellen: -f"Oeft iBuf, v Beznlden. fpr\ pro mm, im Reklameteil 3.76 Gulden. s.Z. Ist Anseigenpreisliste Nr. 4 gültVg. % SohriMeltunr. Telefon 77 19 83, ,77 198«j&Ä Postgiro 389138. Bankkonten ; ««W Künsche i? Handelsbank N.V., V'jgendam 8-10. Han- "V. Telefon %13 47 (Sammelnummer)Ber- -r: - delstrust West N.V., Keizersgr. 569-571. ; Iliter Schrlftleltipig: Berlin BW.eB, Clui. !' ■'] Zeitung Bank v. Nederl. Arbeid Keizersgr. - lottenstr. 82, Telefon: 17 33 25 Deutsche N.V.," Nr. 452, Postf. 1000. Gem.-Giro D 6ioo. ■ Mistel." HüalfS säitop I inNiederlandenden • * te*,Nunimer > * 201 K-■>:' Amsterdam,'Montag, 21. Dezember 1942;• * Jahrgang 3 Graf Ciano beim Führer Blick nach Italien DZ B'om, Mitte Dezember. Seit Wochen führt England.-einen Ver- leumdungsfeldzug gegen Italien, Unter- Politische und militärische Besprechungen in Anwesenheit Görmgs und Ribbentrops mit dem italienischen streicht ihn mit Bombardierungen italieni-' scher Städte und glaubt, damit irgendwie — Aussenminister und Marschall Cavallero Zusammenkunft im Zeichen des entschlossen Willens der Achsenmächte, im Denken der italienischen Öffentlichkeit Fuss fassen und die Stimmung „welch" alle Kräfte zur Erringung Endsieges einzusetzen Geiste * des im unerschütterlicher Waffenbrüderschaft machen zu können., Auch hier irrt sich - >/<•(£■; % '•>'•'■'■ '"v-i 'vi England! In einer Stunde, in der duqoh Führerhauptier, ■' Aus dem 20. -

A. Michailowa, 19 Ada Alsop, 6 Adele Kern, 11 Adrijenko, 18 Alda Noni

Index A. Michailowa, 19 Berndhard Sonnersted, 17 Diana Eustrati, 7 Erna Sack, 11, 16, 22, 26, 27 Gabirella Besanzoni, 22 Ada Alsop, 6 Bernhard Sonnerberg, 20 Dora Labette, 18 Erna Spoorenberg, 7, 18 Gabriella Besanzoni, 12, 22, 23 Adele Kern, 11 Blanche Thebom, 27 Dorothy Kirsten, 8, 12 Ernestine Schumann-Heink, 12, Gabriella Gatti, 10 Adrijenko, 18 Borgioli / Bettore, 23 Dorothy Manski, 6 21 Galiano Masini, 20 Alda Noni, 11, 21 BotelL, 25 Dorothy Maynor, 7, 27 Eugenia Bronskaya, 5 Galliano Masini, 17 Alessandro Valente, 17, 19 Brita Herzberg, 6 Dusolina Giannini, 10, 21 Eugenia Burzio, 22 Georges Thill, 14, 17, 23 Alexander Sved, 20 Evan Williams, 4 Georgi Boue, 6 C. Kulmann / E. Storm, 21 Edith Oldrup, 4 Alfons F¨ugel, 8 Ezio Pinza, 16 Gertrud R¨unger, 11 Carel Butter, 25 Edith Oldrup / Otte Svendsen, 4 Alma Gluck, 11, 22 Gertrude Wettergren, 21 Carl Gunther, 19 Edward Johnson, 20 F. de Lucia / G. Huguet, 8 Althouse / Reimers, 9 Giacomo Lauri-Volpi, 12, 21 Carl Joken, 20 Edwig von Debicka, 5 Fanny Heldy, 6 Annelier Kupper, 15 Gianna Pederzini, 10 Carla Martinis, 9 Eide Norena, 7 Fedor Shaliapin, 5, 14, 15, 24 Anny Schlemm / Hans Braun, 8 Gianni Poggi, 23 Carlo Galeffi, 13 Eileen Farrell, 27 Felicie Huni-Mihacsek, 22 Anny von Stosch, 6 Giovanni Malipiero, 5, 8 Carlo Tagliabue, 13 Einar Andersson, 19 Felicie Lyne, 6 Antenore Reali, 10 Giuseppe Campanari, 26 Carol Brice, 20 Einar Beyron, 20 Fernando de Lucia, 23 Antonio Cortis, 19 Giuseppe Danise, 13, 17 Celestina Boninsegna, 5 Einar Norby, 4, 19, 20 Florence Austral, 22 Antonio Scotti, 13 -

RIAS Bandarchiv 10.01.14.09

Bandnr. Sparte Titel Werk / Album Komponist Orchester Interpret Jahrgang Stichworte 0002 Club 18, Jazz Mr. Mith goes to town The Chico Hamilton Qintet 0003 Club 18, Jazz Such sweet thunder Duke Ellington 1951 0004 Club 18 Jack´s blues George Russell George Russell and his smalltet 0005 Club 18, Jazz Maniac Ferguson Orchestra Joe Malni ten Sax 0006 Club 18, Jazz The King David suite Lionel Hampton Dimitri Metropulos Lionel Hampton, Vibra. 0007 Club 18, Jazz Confusion blues Bob Brookmeyer 0008 Club 18, Jazz I´ll remember april Gene de Paul Modern Jazz quintet 1941 0009 Club 18, Jazz Out of nowhere Dave Brubeck 0010 Club 18, Jazz Le souk Dave Brubeck 0011 Club 18, Jazz Laura The Cahrlie Ventura quintet 0012 Club 18, Jazz avalon Charlie Ventura 1949 0013 Club 18, Jazz departure at ten Karel Flach Orchester 0014 Club 18, Jazz When the saints go marching in Dixieland rhythm king 0015 Club 18, Jazz domicile Joki Freund & Albert Mangelsdorff sextet 0016 Club 18, Jazz going my hemingway Hans Koller new Jazz stans 0017 Club 18, Musical New girl in town Musical: New girl in town Bob Merrill Jazz goes to broadway 0018 Club 18, Jazz Riverside blues Dixieland rhythm king 0018 a enfällt 0019 Club 18, Jazz take the a train Billy Strayhorn Dave Brubeck 0020 Club 18, Jazz abstract art mit Interview Buddy de Franco Quintet 0021 Club 18, Jazz Ralph´s new blues Milt Jackson Modern Jazz Quintet 0022 Club 18, Musical The best thing for you Musical: Call me Madam Irwing Belin 1950 0023 Club 18, Jazz two beats or not two beats Bobby Hackett 0025 Club 18, Jazz -

5-2019 Vocal, Ol-Z

78 rpm VOCAL RECORDS MAGDA OLIVERO [s] 3575. 12” Green Cetra BB 25028 [2-70330-II/2-70331-II]. ADRIANA LECOUVREUR: Io sono l’umile ancella / ADRIANA LECOUVREUR: Poveri fiori gemme (Cilèa). Just about 1-2. $35.00. MARIA OLSZEWSKA [c] 2470. 12” Red acous. Polydor 72778 [753av/882av]. TRAUME / SCHMERZEN (Wagner, from Wesendonck Lieder). Gleaming mint copy. Just about 1-2. $35.00. 2413. 12” Red acous. Polydor 72778 [753av/882av]. Same as preceding listing [#2470]. Few lightest superficial mks., cons. 2. $30.00. AUGUSTA OLTRABELLA [s] 3073. 12” Italian Gram. DB 2828 [2BA1204-II/2BA1205-I] IL DIBUK: Eccoti, bellal amica / IL DIBUK: Ma ora torno mverso l’anima tua (Rocca). With GINO DEL SIGNORE [t]. Orch. dir. Giuseppe Antonicelli. Just about 1-2. $12.00. COLIN O’MORE [t] 1475. 10” Brown Shellec Vocalion 24031 [9503/ ? ]. WERTHER: Pourquoi me réveiller / MANON: Le rêve (both Massenet). Just about 1-2. $8.00. SIGRID ONEGIN [c] 1322. 10” Purple acous. Brunswick 10118 [12157/12013]. VAGGVISA (ar. Raucheisen) / HERDEGOSSEN (Berg). Side one piano acc. Michael Raucheisen. Side two with orch. Just about 1-2. $8.00. 1677. 10” Purple acous. Brunswick 10132 [ ? / ? ]. DER LINDENBAUM (Schubert) / ES IST BESTIMMT IN GOTTES RATH (Mendelssohn). Just about 1-2. $8.00. 3173. 12” Red Schall. Grammophon 72714 (043336/043337) [1462s/1461s]. SAPPHISCHE ODE (Brahms) / DER KREUZZUG (Schubert). Piano acc. In absolutely top condition. Just about 1-2. $25.00. 2643. 12” Red Scroll “Z”-type shellac Victor 7320 [CLR5799- II/CLR5800-I]. SAMSON ET DALILA: Printemps qui commence/ SAMSON ET DALILA: Mon coeur (Saint- Saëns). -

533-Larry Adler, Harmonica with John Kirby Orchestra: Star Dust/: Creole Love Call

533-Larry Adler, harmonica with John Kirby orchestra: Star dust/: Creole love call. Decca BM 4294.US. (V+) . P.50:- 9832-Larry Adler (The virtuoso of the mouth organ): Japanese sandman / Somebody stole my gal/: Some of these days / Dardanella. Decca F 6421.UK. (E-) . P.75:- 9802-Larry Adler, the virtouse of the Mouth-Organ: Cheek to cheek/: Isn´t this a lovely day, Top Hat. Rex 8650.UK. (V) . P.50:- 1702-Juan Akoni, ukulele w piano acc.: Hawaiian Butterfly/: What do you want to make those eyes at me for. Zonophone Rec. 1847.UK. (E-) . P.100:- 301-Peter Alexander och Sunshinekvartetten, Adalbert Luczkowskis orkester: Tschip-Tschiu-Tschi, F/: Cara mia, V. Polydor 49491.S, DE. (E) . P.50:- 920-Peter Alexander, Die Mickeys und das metropol-Tanzorchester: Hannelore, Marschfox/: Bella, bella Donna, F. Odeon SD 5732.Austria.1953 (N-) . P.50:- 1910-All Star Stompers: Hotter than that/: Big butter and egg man. Gazell 1016.US, SE.1947 (E+) from Circle J 1025 resp J 1024. P.100:- 1701-Henry Allen and orchestra, voc: Allen: Rosetta/: Dinah Lou, F. Parlophone R 2886.US. (E+) . P.125:- 1200-Gitta Alpar mit Orchesterbegleitung, Leitung: Dr. Weissmann: DasVellchen vom Montmartre: Warum weiss dein Herz nichts von mir/: Ich sing mein Lied im Regen und Schnee. Odeon O 11412.DE. (V) . P.30:- 1805-Fransisco Alves com Orchestra, Dir: Lirio Panicali: Chuvas de veräo, samba/: Maria Bonita, cancäo Mexicana. Odeon 12923.Brasil. (E+) . P.75:- 2011-Fransisco Alves com Eduardo Patané e sua Orquestra: Velhas cartas de amor, samba/: A noite triste em que vocé näo vem, valsa cancao. -

THIS DOCUMENT IS COMPILED by ROBERT JOHANNESSON, Fader Gunnars Väg 11, S-291 65 Kristianstad, Sweden and Published on My

THIS DOCUMENT IS COMPILED BY ROBERT JOHANNESSON, Fader Gunnars väg 11, S-291 65 Kristianstad, Sweden and published on my website www.78opera.com It is a very hard work for me to compile it (as a hobby), so if you take information from it, mention my website, please! The discographies will be updated about four times a year. Additions and completitions are always welcome! Contact me: [email protected] WACHTER, Ernst 1872, 19/5, Mühlhausen - 1931, August, Leipzig. Bass. Debut 1894 Dresden. G&T, Dresden 1902 1. 2290B Lustigen Weiber von Windsor (Nicolai): Als Büblein klein 42741 (7") 2. 798x Zauberflöte (Mozart): In diesen heil'gen Hallen 42857 3. 799x Zauberflöte (Mozart): O Isis und Osiris 42858 4. 800x Juive (Halévy): Arie des Kardinals 42859 5. 801x Lustigen Weiber von Windsor (Nicolai): Als Büblein klein 42860 6. 802x Der Wanderer (Schubert) 42861 7. 803x Goldene Kreuz (Brüll): Wie anders war es (Bombardonlied) 42862 WACKERS, Cova 1909, 3/4, Wuppertal – 1985, 22/10, Frankfurt a.M. Soprano. Debut in Köln. Polydor, Berlin 1942 1876GS9 Meistersinger von Nürnberg (Wagner): Hat man mit dem Schuhwerk nicht seine Not! (w. Nissen) unpubl 1876½GS9 d:o 67920 1879GS9 Meistersinger von Nürnberg (Wagner): Quintett (w. Arndt-Ober, Kraayvanger, Zimmermann & Nissen) unpubl 1879½GS9 d:o 67921 WAERMÖ, Einar 1901, 13/3, Grängesberg – 1983. Tenor. Columbia, Stockholm 1928-08-23/24 W44328 Folkvisa (Merikanto) 8589 W44329 Land, du välsignade (Althén) 8590 W44330 Serenad (Widéen) 8589 W44331 Lycka ske landet (NordQvist) 8590 W44332 Värmlänningarne (Randel): Farväl nu med lycka 8594 W44333 Den store hvide flok (Grieg) 8591 W44334 Det är solsken där borta (Solsk.s.5) (Hultman) 8596 W44335 Låt oss sprida solsken (Solsk.s.6) (Hultman) 8596 W44336 Ett hem om än så ringa (Solsk.s.89) (Hultman) 8597 W44337 Glöm aldrig bort de kära (Solsk.s.92) (Hultman) 8597 W44343 Blommande sköna dalar (Häggbom) (w. -

Musikdrucke, Notenblätter Und -Hefte

Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg, Zentrum für Populäre Kultur und Musik Schellackplattensammlung: Schellackplatten aus Privatbesitz Stand: 14.09.2016 Schellackplatten aus Privatbesitz 170 Schellack-Schallplatten (73 im Format 12 Zoll, 97 im Format 10 Zoll) aus der Zeit um 1920 bis 1950. Bestand 1: Es handelt sich um eine Schenkung vom April 2016 aus privatem Familien-Besitz, zusammen mit einigen Büchern (für die Bibliothek des ZPKM) und Polyphon Lochplatten (siehe S 0348, Nachweis in Kalliope). Die Schellackplatten wurden als "Nachfolger" der Lochplatten nach dem Umzug der Kaufmannsfamilie von Frankfurt am Main nach Freiburg im Breisgau zum Hausgebrauch erworben. Bestand 2: Die Schellackplatten wurden dem ZPKM im April 2016 (Nachlieferung im September 2016) privat von einem Juristen aus Freiburg als Geschenk übergeben. (Quelle: http://kalliope-verbund.info/DE-611-BF-55356: Schellackplatten aus Privatbesitz) Stand: 14. September 2016 Seite 1 von 10 Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg, Zentrum für Populäre Kultur und Musik Schellackplattensammlung: Schellackplatten aus Privatbesitz Stand: 14.09.2016 Im Einzelnen: Bestand 1: 47 Schellackplatten, 1 Vinyl-Single (separiert), ca. 1940er bis 1950er Jahre: 37 Schellackplatten im Format 12 Zoll 10 Schellackplatten im Format 10 Zoll 1 Schallplattenständer für 50 Platten (separiert) Lieder aus Oper und Operette, Klassik, Volkslieder / Volkstümliches. Es handelt sich um folgende Titel: 1: Beethoven: Pathetik / Mondscheinsonate; 2: Beethoven: Frühlingssonate; 3: Beethoven: Violinkonzert 1 / 2; 4: Eg: Egmont-Ouvertüre; 5: Bach: Toccate / Fuge; 6: M. Bruch: Violinkonzert g-moll; 7: Schubert: h-moll-Sinfonie / Unvollendete; 8: Schubert: h-moll-Sinfonie / Unvollendete; 9: Liszt: Tarantella; 10: Liszt: Ungarische Rhapsodie; 11: Liszt: Liebestraum 1 / Ave Maria; 12: Haydn: Streichkonzert C-Dur / Mozart: Streichkonzert B-Dur; 13: Schubert: Rosamunde / Balletmusik; 14: Weber: Aufforderung zum Tanz; 15: Puccini: Wie eiskalt / Gounod: Gegrüßt sei; 16: Puccini: Liebesduett; 17: Puccini: Nur d.