Geographies of Production and the Contexts of Politics: Dis-Location and New Ecologies of Fear in the Veneto Citta© Diffusa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sommario Rassegna Stampa

Sommario Rassegna Stampa Pagina Testata Data Titolo Pag. Rubrica Unione Province d'Italia 21 Il Sole 24 Ore 02/02/2012 "DEREGULATION OK, MA SI PUO' FARE DI PIU'" (R.Bocciarelli) 3 6 Italia Oggi 02/02/2012 ORA E' IL PD CHE DIFENDE LE PROVINCE (G.Pistelli) 4 11 Gazzetta di Parma 02/02/2012 LIBERALIZZAZIONI, OK DI BANKITALIA: "MASI PUO' E SI DEVE FARE 5 DI PIU' 9 Il Giornale di Reggio 02/02/2012 PROVINCE: PD E PDL SMEMORATI "A ROMA LE VOLEVANO ABOLIRE" 6 1 La Tribuna di Treviso 02/02/2012 SALVA-MURARO NASCE L'ASSE LEGA-SEL-UDC (E.Pucci) 7 1 L'Ordine 02/02/2012 CONSIGLIO PROVINCIALE SULLE PROVINCE: UN'EUTANASIA 8 POLITICA (E.Russo) 23 Messaggero Veneto - Ed. Pordenone 02/02/2012 SALVA-PROVINCIA,NON C'E' ACCORDO 11 AgrigentoWeb.it (web) 01/02/2012 CONSIGLIO PROVINCIALE, APPROVATO ODG SUL RIORDINO DELLE 12 PROVINCE. Arezzo Notizie (web) 01/02/2012 PDL: MOZIONE UPI, SE NON C'ERA IL PDL SAREBBE VENUTO MENO 14 IL NUMERO LEGALE Asca.it 01/02/2012 LIBERALIZZAZIONI: PROVINCE, NO ALLA TESORERIA UNICA 15 14 Calabria Ora - Ed. Catanzaro 01/02/2012 "NO ALL'ITALIA SENZA PROVINCE" 16 31 Calabria Ora - Ed. Cosenza e Provincia 01/02/2012 PROVINCE ACCORPATE ALLE REGIONI: MORELLI NON CI STA 17 Corrierediragusa.it (web) 01/02/2012 POCHI INTIMI PER DIRE NO ALL'ABOLIZIONE DELLE PROVINCIE 18 Daunianews.it (web) 01/02/2012 FOGGIA, IL PD DIFENDE LE PROVINCE 19 Diariodelweb.it (web) 01/02/2012 PODESTA': IL DECRETO SVUOTA IL VALORE E IL SIGNIFICATO DELLE 20 PROVINCE 9 E Polis Bari 01/02/2012 LE PROVINCE IN CORO "NO ALL'ABOLIZIONE" 21 Freemondoweb.com (web) 01/02/2012 SOPPRESSIONE PROVINCE: I PRO E CONTRO DELLON. -

SAMPLE SYLLABUS Spring 2021–History of Immigration HIST-UA 9186 F01

SAMPLE SYLLABUS Spring 2021–History of Immigration HIST-UA 9186 F01 Class Description: This four credit course explores how the dynamics of migration have shaped identity and citizenship. By providing students with a range of theoretical approaches, the course will address questions of migration, national identity and belonging from a multidisciplinary perspective drawing from (amongst other fields): Sociology, History, Geo-Politics, Gender Studies, Black European Studies, and Cultural Studies. Taking the so called “refugee crisis” as a starting point, the course will pay particular attention to the figure and representation of the “migrant” going from Italian mass migration in the late 19th century to the migrants crossing every day the waters of the Mediterranean in order to reach Fortress Europe. Yet, a course on migration processes undertaken in Italy cannot limit itself to a purely theoretical framework. Migration means movements of people bringing along personal histories, families and cultural backgrounds. Furthermore the presence of migrants, refugees and asylum seekers reaching Europe is having a significant impact on the current social and political agenda of European government, as in the case of Italy. Therefore the course will include a series of fieldtrips aimed at showing students how immigrants, refugees and asylum seekers insert themselves into the labor market and society in Italy. Inclusion, Diversity, Belonging and Equity NYU is committed to building a culture that respects and embraces diversity, inclusion, and equity, -

Le Tavole Statistiche Fuori Testo

Tavole statistiche Elenco delle tavole statistiche fuori testo Tirature e vendite complessive dei giornali quotidiani per area di diffusione e per categoria (2003-2004-2005) Provinciali ....................................................................................................................................................... Tavola I Regionali .......................................................................................................................................................... Tavola II Pluriregionali ............................................................................................................................................... Tavola III Nazionali .......................................................................................................................................................... Tavola IV Economici ....................................................................................................................................................... Tavola V Sportivi .............................................................................................................................................................. Tavola VI Politici ................................................................................................................................................................. Tavola VII Altri ...................................................................................................................................................................... -

01 Lega Nord Storia79 87.Pdf

Anni 1979 – 1978 – 1979 – 1980 – 1981 – 1982 – 1983 – 1984 – 1985 – 1986 - 1987 CRONISTORIA DELLA LEGA NORD DALLE ORIGINI AD OGGI Prima Parte 1979 - 1987 Segreteria Organizzativa Federale 1 Anni 1979 – 1978 – 1979 – 1980 – 1981 – 1982 – 1983 – 1984 – 1985 – 1986 - 1987 Segreteria Organizzativa Federale 2 Anni 1979 – 1978 – 1979 – 1980 – 1981 – 1982 – 1983 – 1984 – 1985 – 1986 - 1987 “LA LEGA E’ COME UN BAMBINO, E’ IL FRUTTO DELL’AMORE. IO SONO CONVINTO CHE QUESTO MOVIMENTO SIA IL RISULTATO DEL LAVORO GENEROSO DI MIGLIAIA DI UOMINI E DI DONNE, CHE SI VOGLIONO BENE. CHE VOGLIONO BENE ALLA CITTA’ DOVE VIVONO, ALLA NAZIONE CUI SI SENTONO DI APPARTENERE. IL BAMBINO E’ CRESCIUTO, HA IMPARATO A CAMMINARE CON LE SUE GAMBE. MA BISOGNERA’ LAVORARE ANCORA PERCHE’ DIVENTI ADULTO E REALIZZI LE SUE AMBIZIONI” UMBERTO BOSSI Da “VENTO DAL NORD” Segreteria Organizzativa Federale 3 Anni 1979 – 1978 – 1979 – 1980 – 1981 – 1982 – 1983 – 1984 – 1985 – 1986 - 1987 FEDERICO 1° DI SVEVIA, IMPERATORE DI GERMANIA MEGLIO CONOSCIUTO COME “FEDERICO BARBAROSSA”, NELL’ANNO 1158 CALO’ SULLE NOSTRE TERRE PER RIAFFERMARE L’EGEMONIA IMPERIALE, PIEGANDO CON LA FORZA QUEI COMUNI LOMBARDI CHE SI OPPONEVANO AL SUO POTERE OPPRESSIVO. I COMUNI DELL’ITALIA SETTENTRIONALE (MILANO, LODI, CREMONA, BRESCIA, BERGAMO, PIACENZA, PARMA, BOLOGNA, MODENA, VERONA, VENEZIA, PADOVA, TREVISO, VICENZA, MANTOVA, FERRARA), DECISI A NON FARSI SOTTOMETTERE DAL DESPOTA BARBAROSSA, SI UNIRONO DANDO VITA ALLA “LEGA LOMBARDA” ED IL 7 APRILE 1167, NEL MONASTERO DI PONTIDA SUGGELLARONO LA LORO ALLEANZA CON UN GIURAMENTO: IL “GIURAMENTO DI PONTIDA”. IL BARBAROSSA TENTO’ IN OGNI MODO DI SCHIACCIARE I RIBELLI MA IL 29 MAGGIO 1176, A LEGNANO, VENNE SONORAMENTE SCONFITTO DECIDENDOSI, COSI’, A TRATTARE PER LA PACE. -

International Press

International press The following international newspapers have published many articles – which have been set in wide spaces in their cultural sections – about the various editions of Europe Theatre Prize: LE MONDE FRANCE FINANCIAL TIMES GREAT BRITAIN THE TIMES GREAT BRITAIN LE FIGARO FRANCE THE GUARDIAN GREAT BRITAIN EL PAIS SPAIN FRANKFURTER ALLGEMEINE ZEITUNG GERMANY LE SOIR BELGIUM DIE ZEIT GERMANY DIE WELT GERMANY SUDDEUTSCHE ZEITUNG GERMANY EL MUNDO SPAIN CORRIERE DELLA SERA ITALY LA REPUBBLICA ITALY A NEMOS GREECE ARTACT MAGAZINE USA A MAGAZINE SLOVAKIA ARTEZ SPAIN A TRIBUNA BRASIL ARTS MAGAZINE GEORGIA A2 MAGAZINE CZECH REP. ARTS REVIEWS USA AAMULEHTI FINLAND ATEATRO ITALY ABNEWS.RU – AGENSTVO BUSINESS RUSSIA ASAHI SHIMBUN JAPAN NOVOSTEJ ASIAN PERFORM. ARTS REVIEW S. KOREA ABOUT THESSALONIKI GREECE ASSAIG DE TEATRE SPAIN ABOUT THEATRE GREECE ASSOCIATED PRESS USA ABSOLUTEFACTS.NL NETHERLANDS ATHINORAMA GREECE ACTION THEATRE FRANCE AUDITORIUM S. KOREA ACTUALIDAD LITERARIA SPAIN AUJOURD’HUI POEME FRANCE ADE TEATRO SPAIN AURA PONT CZECH REP. ADESMEUFTOS GREECE AVANTI ITALY ADEVARUL ROMANIA AVATON GREECE ADN KRONOS ITALY AVLAIA GREECE AFFARI ITALY AVLEA GREECE AFISHA RUSSIA AVRIANI GREECE AGENZIA ANSA ITALY AVVENIMENTI ITALY AGENZIA EFE SPAIN AVVENIRE ITALY AGENZIA NUOVA CINA CHINA AZIONE SWITZERLAND AGF ITALY BABILONIA ITALY AGGELIOF OROS GREECE BALLET-TANZ GERMANY AGGELIOFOROSTIS KIRIAKIS GREECE BALLETTO OGGI ITALY AGON FRANCE BALSAS LITHUANIA AGORAVOX FRANCE BALSAS.LT LITHUANIA ALGERIE ALGERIA BECHUK MACEDONIA ALMANACH SCENY POLAND -

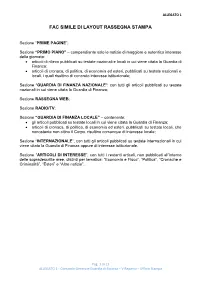

Fac Simile Di Layout Rassegna Stampa

ALLEGATO 1 FAC SIMILE DI LAYOUT RASSEGNA STAMPA Sezione “PRIME PAGINE”; Sezione “PRIMO PIANO” – compendiante solo le notizie di maggiore e autentico interesse della giornata: articoli di rilievo pubblicati su testate nazionali e locali in cui viene citata la Guardia di Finanza; articoli di cronaca, di politica, di economia ed esteri, pubblicati su testate nazionali e locali, i quali risultino di concreto interesse istituzionale; Sezione “GUARDIA DI FINANZA NAZIONALE”: con tutti gli articoli pubblicati su testate nazionali in cui viene citata la Guardia di Finanza; Sezione RASSEGNA WEB; Sezione RADIO/TV; Sezione “GUARDIA DI FINANZA LOCALE” – contenente: gli articoli pubblicati su testate locali in cui viene citata la Guardia di Finanza; articoli di cronaca, di politica, di economia ed esteri, pubblicati su testate locali, che nonostante non citino il Corpo, risultino comunque di interesse locale; Sezione “INTERNAZIONALE”, con tutti gli articoli pubblicati su testate internazionali in cui viene citata la Guardia di Finanza oppure di interesse istituzionale. Sezione “ARTICOLI DI INTERESSE”, con tutti i restanti articoli, non pubblicati all’interno delle sopradescritte aree, distinti per tematica: “Economia e Fisco”, “Politica”, “Cronache e Criminalità”, “Esteri” e “Altre notizie”. Pag. 1 di 13 ALLEGATO 1 - Comando Generale Guardia di Finanza – V Reparto – Ufficio Stampa ALLEGATO 1 TESTATE STAMPA NAZIONALE - QUOTIDIANI Il Sole 24 Ore Corriere della Sera (comprese le edizioni di Milano e Roma) Italia Oggi La Repubblica (comprese le edizioni -

The Role of Italy in Milton's Early Poetic Development

Italia Conquistata: The Role of Italy in Milton’s Early Poetic Development Submitted by Paul Slade to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in December 2017 This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. Signature: ………………………………………………………….. Abstract My thesis explores the way in which the Italian language and literary culture contributed to John Milton’s early development as a poet (over the period up to 1639 and the composition of Epitaphium Damonis). I begin by investigating the nature of the cultural relationship between England and Italy in the late medieval and early modern periods. I then examine how Milton’s own engagement with the Italian language and its literature evolved in the context of his family background, his personal contacts with the London Italian community and modern language teaching in the early seventeenth century as he grew to become a ‘multilingual’ poet. My study then turns to his first published collection of verse, Poems 1645. Here, I reconsider the Italian elements in Milton’s early poetry, beginning with the six poems he wrote in Italian, identifying their place and significance in the overall structure of the volume, and their status and place within the Italian Petrarchan verse tradition. -

A. Manzoni & C. S.P.A. Specifications for Newspapers Owned by GEDI

A. Manzoni & C. S.p.A. Specifications for newspapers owned by GEDI Gruppo Editoriale Newspapers: Repubblica Nazionale, Repubblica Settimanali, Affari e Finanza, edizioni locali di Repubblica (Bari, Bologna, Firenze, Genova, Milano, Napoli, Palermo, Roma e Torino), La Stampa, Il Secolo XIX, Avvisatore Marittimo, Il Mattino di Padova, La Tribuna di Treviso, La Nuova di Venezia e Mestre, Corriere della Alpi, Messaggero Veneto, Il Piccolo, Gazzetta di Mantova, La Provincia Pavese, La Sentinella del Canavese Printing Specifications: Offset and flexographic printing Screen: 37 lines Screen Angles: Cyan 7.5 – Magenta 67.5 – Yellow 82.5 – K 37.5 o 45° if monochrome Tonal Values: Printable minimum of at least 8%, not exceeding all'92%, other forces do not give a guarantee of tonal rendering in print. To be taken into account during the processing of images: the "dot gain" rotary press is an average of 25%. Color Profile: ISO26Newspaper v4 (http://www.ifra.com/WebSite/ifra.nsf/html/CONT_ISO_DOWNLOADS) Color Density: 240% (CMYK) Specifications for the creation of PDF: ISO PDF/X-1a:2001 in high resolution, 200 dpi, compatible with Adobe Acrobat 4.0 (PDF version 1.3). Materials with transparency are not accepted; to handle this is to create a PDF compatible with Acrobat 4 passing in Acrobat Distiller, EPS (created with InDesign, Illustrator, XPress, etc ...) using the profile PDF/X-1a : 2001, with output intent ISO26Newspaper v4. Font: Included in the PDF document- No TrueType - No CID Font Avoid the placement of text on a colored background in negative and / or colored text with a body less than 10 points for the materials in color; avoid the lower bodies with characters pardoned, as well as the wires and multi-colored frames are likely to be compromised any slightest oscillation of the register during printing. -

Rapporto 2019 Sull'industria Dei Quotidiani in Italia

RAPPORTO 2019 RAPPORTO RAPPORTO 2019 sull’industria dei quotidiani in Italia Il 17 dicembre 2012 si è ASSOGRAFICI, costituito tra AIE, ANES, ASSOCARTA, SLC-‐CGIL, FISTEL-‐CISL e UILCOM, UGL sull’industria dei quotidiani in Italia CHIMICI, il FONDO DI ASSISTENZA SANITARIA INTEGRATIVA “Salute Sempre” per il personale dipendente cui si applicano i seguenti : CCNL -‐CCNL GRAFICI-‐EDITORIALI ED AFFINI -‐ CCNL CARTA -‐CARTOTECNICA -‐ CCNL RADIO TELEVISONI PRIVATE -‐ CCNL VIDEOFONOGRAFICI -‐ CCNL AGIS (ESERCENTI CINEMA; TEATRI PROSA) -‐ CCNL ANICA (PRODUZIONI CINEMATOGRAFICHE, AUDIOVISIVI) -‐ CCNL POLIGRAFICI Ad oggi gli iscritti al Fondo sono circa 103 mila. Il Fondo “Salute Sempre” è senza fini di lucro e garantisce agli iscritti ed ai beneficiari trattamenti di assistenza sanitaria integrativa al Servizio Sanitario Nazionale, nei limiti e nelle forme stabiliti dal Regolamento Attuativo e dalle deliberazioni del Consiglio Direttivo, mediante la stipula di apposita convenzione con la compagnia di assicurazione UNISALUTE, autorizzata all’esercizio dell’attività di assicurazione nel ramo malattia. Ogni iscritto potrà usufruire di prestazioni quali visite, accertamenti, ricovero, alta diagnostica, fisioterapia, odontoiatria . e molto altro ancora Per prenotazioni: -‐ www.unisalute.it nell’area riservata ai clienti -‐ telefonando al numero verde di Unisalute -‐ 800 009 605 (lunedi venerdi 8.30-‐19.30) Per info: Tel: 06-‐37350433; www.salutesempre.it Osservatorio Quotidiani “ Carlo Lombardi ” Il Rapporto 2019 sull’industria dei quotidiani è stato realizzato dall’Osservatorio tecnico “Carlo Lombardi” per i quotidiani e le agenzie di informazione. Elga Mauro ha coordinato il progetto ed ha curato la stesura dei testi, delle tabelle e dei grafici di corredo e l’aggiornamento della Banca Dati dell’Industria editoriale italiana La versione integrale del Rapporto 2019 è disponibile sul sito www.ediland.it Osservatorio Tecnico “Carlo Lombardi” per i quotidiani e le agenzie di informazione Via Sardegna 139 - 00187 Roma - tel. -

Representations of Italian Americans in the Early Gilded Age

Differentia: Review of Italian Thought Number 6 Combined Issue 6-7 Spring/Autumn Article 7 1994 From Italophilia to Italophobia: Representations of Italian Americans in the Early Gilded Age John Paul Russo Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.library.stonybrook.edu/differentia Recommended Citation Russo, John Paul (1994) "From Italophilia to Italophobia: Representations of Italian Americans in the Early Gilded Age," Differentia: Review of Italian Thought: Vol. 6 , Article 7. Available at: https://commons.library.stonybrook.edu/differentia/vol6/iss1/7 This document is brought to you for free and open access by Academic Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Differentia: Review of Italian Thought by an authorized editor of Academic Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. From ltalophilia to ltalophobia: Representations of Italian Americans in the Early Gilded Age John Paul Russo "Never before or since has American writing been so absorbed with the Italian as it is during the Gilded Age," writes Richard Brodhead. 1 The larger part of this American fascination expressed the desire for high culture and gentility, or what Brodhead calls the "aesthetic-touristic" attitude towards Italy; it resulted in a flood of travelogues, guidebooks, antiquarian stud ies, historical novels and poems, peaking at the turn of the centu ry and declining sharply after World War I. America's golden age of travel writing lasted from 1880 to 1914, and for many Americans the richest treasure of all was Italy. This essay, however, focuses upon Brodhead's other catego ry, the Italian immigrant as "alien-intruder": travel writing's gold en age corresponded exactly with the period of greatest Italian immigration to the United States. -

In Both Europe and the US, the Topic of Immigration Is Highly

Class code HIST--UA 9186 Name: Prof. Kathryn Lum Instructor Details NYU Home Email Address: [email protected] Office Hours: 13:00-15:00 Thursday Villa Ulivi Office Location: Office # 7 Villa Ulivi Office Extension: 055 5007 317 Semester: Spring 2015 Class Details Full Title of Course: The History of Immigration in the US and Italy from the 1880´s onwards Meeting Days and Times: 15:00-17:45 Thursday Classroom Location: Colletta 1 There are no prerequisites for this course Prerequisites In both Europe and the US, the topic of immigration is highly politicized, Class Description and frequently occupies the center of national and regional debates on identity, citizenship and belonging. On both sides of the Atlantic, the contours of multiculturalism and the question of irregular migration present thorny issues for academics and policy makers. This course will provide a general comparative (US/Europe) introduction to the history of migration, from the late 1880´s to the present day in order to help students develop a basic historical framework that will allow them to more deeply understand contemporary migration policy and debates surrounding integration and multiculturalism. The experiences of a number of European countries will be looked at in depth: the UK, France, Italy, and Germany. Throughout the course, we will be exploring deeper questions of national identity and belonging, both historically and cross-nationally. We will begin by looking at mass Italian migration to the US in the late 19th and early Twentieth Centuries, discussing how the first waves of Italian migrants were categorized and racialized and how they were inserted into the existing racial order in the US. -

ANDREI BELOBORODOV and ITALY Russia's Silver

ANDREI BELOBORODOV AND ITALY Andrej Shishkin Russia's Silver Age was greatly indebted to the wave of Italophilia which affected the works of the most diverse writers, including Dmi- trii Merezhkovskii, Viacheslav Ivanov, Mikhail Kuzmin, Maksimilian Voloshin, Nikolai Berdiaev, Vasilii Rozanov, Anna Akhmatova, Osip Mandel'shtam, Boris Zaitsev, and Pavel Muratov. Encounters with the Italian "Elysium" served both as the inspiration for art and as the symbol of physical death and spiritual immortality. 1 Viacheslav Iva- nov was speaking for many of his contemporaries when he declared: "Love for Italy is an indicator of cultural Ioftiness. One can judge the character of an age by the way it loves Italy and what it chooses to love in her".2 This was the context from which emerged Andrei Beloborodov (1886-1965), one of the most originai Russian artists to have devoted his work to Italy. For various reasons Beloborodov's legacy has remained neglected and forgotten until quite recently.Now he is beginning to be recognized as a major contributor to the com- plex relationship between Italy and Russian culture. 3 I "I find the idea of a trip to Italy quite possible," wrote Kuzmin in his diary on 31 December 1934, foreseeing his impending death; M. Kuzmin, Dnevnik 1934 g. (St Petersburg 1998) 145. As Gleb Morev notes, the idea of the sacred end of a Iife-path is here linked to the image of the entrante to paradise and immortality; Gleb Morev, "Kazus Kuzmina," lhid. 23-24. 2Russko-italianskii arkhiv , Trento 1997, 503. See allo P. Deotto, /n viaggio per ralizzare un sogno.