The Challenges of Constructing Legitimacy in Peacebuilding

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AFGHANISTAN - Base Map KYRGYZSTAN

AFGHANISTAN - Base map KYRGYZSTAN CHINA ± UZBEKISTAN Darwaz !( !( Darwaz-e-balla Shaki !( Kof Ab !( Khwahan TAJIKISTAN !( Yangi Shighnan Khamyab Yawan!( !( !( Shor Khwaja Qala !( TURKMENISTAN Qarqin !( Chah Ab !( Kohestan !( Tepa Bahwddin!( !( !( Emam !( Shahr-e-buzorg Hayratan Darqad Yaftal-e-sufla!( !( !( !( Saheb Mingajik Mardyan Dawlat !( Dasht-e-archi!( Faiz Abad Andkhoy Kaldar !( !( Argo !( Qaram (1) (1) Abad Qala-e-zal Khwaja Ghar !( Rostaq !( Khash Aryan!( (1) (2)!( !( !( Fayz !( (1) !( !( !( Wakhan !( Khan-e-char Char !( Baharak (1) !( LEGEND Qol!( !( !( Jorm !( Bagh Khanaqa !( Abad Bulak Char Baharak Kishim!( !( Teer Qorghan !( Aqcha!( !( Taloqan !( Khwaja Balkh!( !( Mazar-e-sharif Darah !( BADAKHSHAN Garan Eshkashem )"" !( Kunduz!( !( Capital Do Koh Deh !(Dadi !( !( Baba Yadgar Khulm !( !( Kalafgan !( Shiberghan KUNDUZ Ali Khan Bangi Chal!( Zebak Marmol !( !( Farkhar Yamgan !( Admin 1 capital BALKH Hazrat-e-!( Abad (2) !( Abad (2) !( !( Shirin !( !( Dowlatabad !( Sholgareh!( Char Sultan !( !( TAKHAR Mir Kan Admin 2 capital Tagab !( Sar-e-pul Kent Samangan (aybak) Burka Khwaja!( Dahi Warsaj Tawakuli Keshendeh (1) Baghlan-e-jadid !( !( !( Koran Wa International boundary Sabzposh !( Sozma !( Yahya Mussa !( Sayad !( !( Nahrin !( Monjan !( !( Awlad Darah Khuram Wa Sarbagh !( !( Jammu Kashmir Almar Maymana Qala Zari !( Pul-e- Khumri !( Murad Shahr !( !( (darz !( Sang(san)charak!( !( !( Suf-e- (2) !( Dahana-e-ghory Khowst Wa Fereng !( !( Ab) Gosfandi Way Payin Deh Line of control Ghormach Bil Kohestanat BAGHLAN Bala !( Qaysar !( Balaq -

Badghis Province

AFGHANISTAN Badghis Province District Atlas April 2014 Disclaimers: The designations employed and the presentation of material on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. http://afg.humanitarianresponse.info [email protected] AFGHANISTAN: Badghis Province Reference Map 63°0'0"E 63°30'0"E 64°0'0"E 64°30'0"E 65°0'0"E Legend ^! Capital Shirintagab !! Provincial Center District ! District Center Khwajasabzposh Administrative Boundaries TURKMENISTAN ! International Khwajasabzposh Province Takhta Almar District 36°0'0"N 36°0'0"N Bazar District Distirict Maymana Transportation p !! ! Primary Road Pashtunkot Secondary Road ! Ghormach Almar o Airport District p Airfield River/Stream ! Ghormach Qaysar River/Lake ! Qaysar District Pashtunkot District ! Balamurghab Garziwan District Bala 35°30'0"N 35°30'0"N Murghab District Kohestan ! Fa r y ab Kohestan Date Printed: 30 March 2014 08:40 AM Province District Data Source(s): AGCHO, CSO, AIMS, MISTI Schools - Ministry of Education ° Health Facilities - Ministry of Health Muqur Charsadra Badghis District District Projection/Datum: Geographic/WGS-84 Province Abkamari 0 20 40Kms ! ! ! Jawand Muqur Disclaimers: Ab Kamari Jawand The designations employed and the presentation of material !! District p 35°0'0"N 35°0'0"N Qala-e-Naw District on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, Qala-i-Naw Qadis city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation District District of its frontiers or boundaries. -

National Area-Based Development Programme

Empowered lives. Resilient nations. NATIONAL AREA-BASED DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME 2014 Second Quarterly PROJECT PROGRESS REPORT UNITED NATIONS DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME DONORS PROJECT INFORMATION Project ID: 00057359 (NIM) Duration: Phase III (July 2009 – June 2015) ANDS Component: Social and Economic Development Contributing to NPP One and Four Strategic Plan Component: Promoting inclusive growth, gender equality and achievement of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) CPAP Component: Increased opportunities for income generation through promotion of diversified livelihoods, private sector development, and public private partnerships Total Phase III Budget: US $294,666,069 AWP Budget 2014: US $ 52,608,993 Un-Funded amount 2014: US $ 1,820,886 Implementing Partner Ministry of Rural Rehabilitation and Development (MRRD) Responsible Party: MRRD and UNDP Project Manager: Abdul Rahim Daud Rahimi Chief Technical Advisor: Vacant Responsible Assistant Country Director: Shoaib Timory Cover Photo: Kabul province, Photo Credit: | NABDP ACRONYMS ADDPs Annual District Development Plans AIRD Afghanistan Institute for Rural Development APRP Afghanistan Peace and Reintegration Programme ASGP Afghanistan Sub-National Governance Programme DCC District Coordination Councils DDA District Development Assembly DDP District Development Plan DIC District Information Center ERDA Energy for Rural Development of Afghanistan GEP Gender Empowerment Project IALP Integrated Alternative Livelihood Programme IDLG Independent Directorate of Local Governance KW Kilo Watt LIDD Local Institutional Development Department MHP Micro Hydro Power MoF Ministry of Finance MoRR Ministry of Refuge and Repatriation MRRD Ministry of Rural Rehabilitation and Development NABDP National Area Based Development Programme PEAC Provincial Establishment and Assessment Committees RTD Rural Technology Directory RTP Rural Technology Park PMT Provincial Monitoring Teams UNDP United Nations Development Programme SPVHS Solar Photovoltaic Voltage Home System SDU Sustainable Development Unit TABLE OF CONTENTS I. -

New Delhi Supplies Three Cheetal Helicopters to Kabul

Eye on the News [email protected] Truthful, Factual and Unbiased Vol:IX Issue No:260 Price: Afs.15 SATURDAY . APRIL 25 . 2015 -Sawr 05, 1394 HS www.afghanistantimes.af www.facebook.com/ afghanistantimeswww.twitter.com/ afghanistantimes Security forces CASA-1000 launch operation Spanta rebuffs aid New Delhi supplies three TO RESCUE 31 electricity HOSTAGES money ended up in transmission Cheetal helicopters to Kabul A joint military and police opera- deal signed tion has been launched to track and DAESHS POCKET rescue 31 hostages held for nearly AT Monitoring Desk two months in southern Zabul, local officials told TOLOnews. KABUL: The long-awaited Cen- The operation was launched tral Asia South Asia (CASA-1000) Thursday in Khak Afghan district electricity transmission projected where the abductees were alleg- signed in Istanbul city of Turkey edly transferred soon after being on Friday. kidnapped by unknown armed Based on the agreement signed men on Kabul-Kandahar highway. in October, 2015, the project will "So far, the operation is going bring $45 million in transit reve- on very well and there has been no nue. The project is expected to complaining regarding the opera- export electricity from hydro- tion," head of provincial council power stations in Kyrgyzstan and Ataullah Jan Haqparast said. "If it Tajikistan to Afghanistan and Pa- continues the same way, we hope kistan. The signing ceremony was there will be achievements." attended by energy and water The abduction incidents have ministers of the four countries. increased since February 24 the The CASA-1000 power trans- first incident when 31 bus passen- mission line would transmit 1300 gers were kidnapped by armed megawatt electricity. -

AIHRC-UNAMA Joint Monitoring of Political Rights Presidential and Provincial Council Elections Third Report 1 August – 21 October 2009

Afghanistan Independent Human Rights Commission AIHRC AIHRC-UNAMA Joint Monitoring of Political Rights Presidential and Provincial Council Elections Third Report 1 August – 21 October 2009 United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan UNAMA Table of Contents Summary of Findings i Introduction 1 I. Insecurity and Intimidation 1 Intensified violence and intimidation in the lead up to elections 1 Insecurity on polling day 2 II. Right to Vote 2 Insecurity and voting 3 Relocation or merging of polling centres and polling stations 4 Women’s participation 4 III. Fraud and Irregularities 5 Ballot box stuffing 6 Campaigning at polling stations and instructing voters 8 Multiple voter registration cards 8 Proxy voting 9 Underage voting 9 Deficiencies 9 IV. Freedom of Expression 9 V. Conclusion 10 Endnotes 11 Annex 1 – ECC Policy on Audit and Recount Evaluations 21 Summary of Findings The elections took place in spite of a challenging environment that was characterised by insecurity and logistical and human resource difficulties. These elections were the first to be fully led and organised by the Afghanistan Independent Election Commission (IEC) and the Afghan National Security Forces (ANSF) took the lead in providing security for the elections. It was also the first time that arrangements were made for prisoners and hospitalised citizens, to cast their votes. The steady increase of security-related incidents by Anti-Government Elements (AGEs) was a dominant factor in the preparation and holding of the elections. Despite commendable efforts from the ANSF, insecurity had a bearing on the decision of Afghans to participate in the elections Polling day recorded the highest number of attacks and other forms of intimidation for some 15 years. -

Challenge of Constructing Legitimacy in Peacebuilding: Case of Afghanistan

Challenge of Constructing Legitimacy in Peacebuilding: Case of Afghanistan Final Report Daisaku Higashi September 2008 The Author Daisaku Higashi is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Political Science at the University of British Columbia (UBC) in Canada. He is currently conducting research in Afghanistan and Timor Leste that seeks effective policies that would create domestic legitimacy of peacebuilders in the eyes of local people and leaders. From 1993 to 2004, he worked as a TV program director specializing in political analysis of international conflicts and produced numerous documentaries on international affairs, such as the Vietnam War, the Middle East peace negotiations, the North Korean nuclear crisis, and nation building in Iraq. The documentary that he directed titled ―Rebuilding Iraq: Challenge of the United Nations‖ received the silver medal from the UN Correspondents Association in 2004, acknowledging it as the second-best report on the UN in the world. He also published several books, which have been used in many Japanese universities as references. As a fellow of the Toyota Foundation, he has been conducting research on peacebuilding at the UN Headquarters and in post-conflict regions since 2006. Preface and Acknowledgments Legitimacy in world politics has been the focus of both global attention and scholarly study in recent years, yet its role in peacebuilding has not been well studied. It is often remarked in both public and scholarly discourse that legitimacy is critical for success in creating sustainable peace -

A Survey of the Afghan People House No

AFGHANISTAN IN 2013 A Survey of the Afghan People AFGHANISTAN IN 20 AFGHANISTAN 13 A Survey of the Afghan People House No. 861, Street No. 1, Sub-Street of Shirpour Project, Kabul, Afghanistan www.asiafoundation.org AFGHANISTAN IN 2013 A Survey of the Afghan People AFGHANISTAN IN 2013 A Survey of the Afghan People Project Design and Direction The Asia Foundation Editor Nancy Hopkins Report Author Keith Shawe Assistant Authors Shahim Ahmad Kabuli, Shamim Sarabi, Palwasha Kakar, Zach Warren Fieldwork Afghan Center for Socio-economic and Opinion Research (ACSOR), Kabul Report Design and Printing The Asia Foundation AINA Afghan Media, Kabul ©2013, The Asia Foundation About The Asia Foundation The Asia Foundation is a nonprofit international development organization committed to improving lives across a dynamic and developing Asia. Informed by six decades of experience and deep local expertise, our programs address critical issues affecting Asia in the 21st century—governance and law, economic development, women's empowerment, environment, and regional cooperation. In addition, our Books for Asia and professional exchange programs are among the ways we encourage Asia's continued development as a peaceful, just, and thriving region of the world. Headquartered in San Francisco, The Asia Foundation works through a network of offices in 18 Asian countries and in Washington, DC. Working with public and private partners, the Foundation receives funding from a diverse group of bilateral and multilateral development agencies, foundations, corporations, and individuals. In 2012, we provided nearly $100 million in direct program support and distributed textbooks and other educational materials valued at over $30 million. For more information, visit asiafoundation.org Afghanistan in 2013 Table of Contents 1. -

The ANSO Report (1-15 November 2011)

CONFIDENTIAL— NGO use only No copy, forward or sale © INSO 2011 Issue 85 REPORT 1‐15 November 2011 Index COUNTRY SUMMARY Central Region 1-5 With echoes of mid-year 2010, the recent for comparative graphs). Northern Region 6-10 spate of NGO staff abductions in Faryab In broader conflict dynamics, IED’s re- Western Region 11-12 provided the defining dynamic affecting main a keystone tactical element with this the NGO community this period, with 4 period being no exception. Despite minor Eastern Region 13-16 separate incidents (including 3 actual ab- periodic fluctuations, the detonation (both ductions and one near miss) reported in Southern Region 17-21 actual and premature) to discovery rate just over a fortnight. The death of 2 NGO ANSO Info Page 22 remains relatively stable at roughly 50/50, a national staff members in one incident also rate that also is generally unaffected by the proved to be the most significant occur- changing volumes (+/-) of device deploy- rence resulting from these. While the exact ment. Of note, civilians remain the most HIGHLIGHTS causative factors of this short-term trend affected, accounting for 55% of all IED remains shrouded, it is likely a mix result- related deaths this period with the ANP NGO abductions in ing from the fluid operational environment Faryab second to this for a further 38%. These in which these incidents happened (AOG statistics bear out the reality that with the migrations, indigenous vs. exogenous 2 NGO staff fatalities continued expansive use of victim operated this period groups, and security force operations), devices, particularly when coupled with the command and control issues related to the high exposure rate these 2 groups experi- Civilians remain most mixed nature of AOG elements through- ence, this will continue to be the case affected by IED detona- out the North, as well as possible local through to the conclusion of 2011. -

Laghman Province - Reference Map

Laghman Province - Reference Map Parun Legend !^ Capital !!! Provincial Centre ! District Centre PANJSHER ! Village Mandol Wama Administrative Boundaries Dara Du Ab International Wama Province District Transportation Elevation (meter) Primary Road > 5000 Chakar Kani Bala Secondary Road 4,001 - 5,000 Chashedar Chakar Katepayen NURISTAN 3,001 - 4,000 Other Road 2,501 - 3,000 Dahan Nijrab Geran Nurgaram U Airport 2,001 - 2,500 Choshak Khad Zar Nekah Sang Paitak Dahi Khanda p 1,501 - 2,000 Baqoul Kalan Low Airfield Now Safa Paya 1,001 - 1,500 Kalder Obra Daulatshahi River/Lake Kark 801 - 1,000 Bala Dahi Sar Mangal Makel Ari Wa Mangalpour Pour River/Stream 601 - 800 Paitak Neil Khan Dala Angosh 6" Dahi Hospital 401 - 600 Zhorandi Ab Too Gosh Dor " < 400 Awdor 5 Mak Other health facilities Menjaghan 35°0'N Gaman Kashlam Dok Kail Do Koh Mash Khando Chakla Kundi nm Kolal Domer Meyou Bar Kott Schools Suliman Shad Mir Khando Kacha Atorow Rendi Atak Nala Chakla Khojal Sayak Tambala Khando Shair Bakami Chandal Bangari Masmote Chapa Gadyala Mara Chapa Dara Dara(Qala Wais Kulalan Dawlat Shah Kalay) Dawlat Darona Qala Shah Markaz Malangani Wolluswaly Awalak Lambri KUNAR Manan Maho Gor Noora Ganda Gar Bomby Bandak Darangi Che Darata Noori KAPISA Mandor Darzi Noori Hulya Shahi Taely Sufla Koshak Gow Qachar Dum Shama Manda Nuristan(Lokar) Shella Khandow Leach Panda Gul Tapa Kal Wahd Bam Kundi Burawon Ele va tio n Palak Toon Kotta Gumrahi Hussain Wato Samar Hulya Lam Jalam Alasay Tag Paigal Kotwal Ahangaroto Dum Lam Kunda Bam Khando Abelam Kunda Gal Baz -

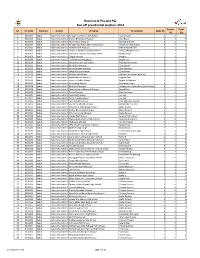

Final List of Pcs and Pss Run-Off Presidential Election, 2014

Final List of PCs and PSs Run-off presidential election, 2014 Female Total No PC Code Province District PC Name PC locatioin Male PS PS PSs 1 0101001 Kabul Kabul-city district 01Ashiqan-wa-Arefan High School Asakzai lane 3 3 6 2 0101002 Kabul Kabul-city district 01Mullah Mahmood Mosque Shur Bazar 3 3 6 3 0101003 Kabul Kabul-city district 01Akhir-e-Jada Mosque Maiwand Street 2 2 4 4 0101004 Kabul Kabul-city district 01Ashiqan-wa-Arefan Secondary School Se Dokan Chandawaul 3 3 6 5 0101005 Kabul Kabul-city district 01Pakhtaferoshi Mosque Pakhta forushi lane 2 3 5 6 0101006 Kabul Kabul-city district 01Daqeqi-e-Balkhi Secondary School Saraji, Ahangari Lane 3 3 6 7 0101007 Kabul Kabul-city district 01Mastoora-e-Ghoori Seconday School Babay Khudi 3 3 6 8 0101008 Kabul Kabul-city district 01Eidgah Mosque Abdgah 3 3 6 9 0101009 Kabul Kabul-city district 01Fatiha-Khana-e-Baghqazi Baghe Qazi 2 2 4 10 0101010 Kabul Kabul-city district 01Aisha-e-Durani High School Pule baghe Umumi 3 2 5 11 0101011 Kabul Kabul-city district 01Bibi Sidiqa Mosque Chendawul 2 1 3 12 0101012 Kabul Kabul-city district 01Sar-e-Gardana Mosque Sare Gardana 1 1 2 13 0101013 Kabul Kabul-city district 01Takya-Khana-e-Omomi Chendawul 3 2 5 14 0101014 Kabul Kabul-city district 01Khawja Safa Mosqe Asheqan wa Arefan Bala Joy 1 1 2 15 0101015 Kabul Kabul-city district 01Baghbankocha Mosque Baghbanlane 2 1 3 16 0101016 Kabul Kabul-city district 01Onsuri-e-Balkhi School Baghe Ali Mardan 3 2 5 17 0101017 Kabul Kabul-city district 01Imam Baqir Mosqe Hazaraha village 2 1 3 18 0101018 Kabul -

Afghanistan: Extremism & Counter-Extremism

Afghanistan: Extremism & Counter-Extremism On July 14, 2020, the United States closed five military bases in Afghanistan per the conditions of the U.S.-Taliban agreement. The deal, signed in February, saw the U.S. promise to withdraw all U.S. forces from the bases in the first 135 days of the deal. The evacuated bases were located in Helmand, Uruzgan, Paktika, and Laghman provinces. The larger bases—Bagram and Kandahar Airfield—located in Kabul and south Afghanistan remain open. (Source: Fox News [1]) On July 13, 2020, Taliban fighters ambushed security forces following a car bomb blast at a government compound in Samangan, northern Afghanistan. The attack killed at least 11 people and wounded over 43 others. The attack was launched close to one of the offices of the National Directorate of Security (NDS), Afghanistan’s main intelligence agency. According to local officials, the Taliban also ambushed a number of other security force checkpoints in Badakhshan, Kunduz, and Parwan. Between the three attacks, 25 people were killed. (Sources: Wall Street Journal [2], Al Jazeera [3]) On June 22, 2020, Javid Faisal, the spokesman for the National Security Council, reported that the previous week was the “deadliest” in the 19-year Afghan war. Releasing the details on Twitter, Faisal alleges that the Taliban carried out over 422 attacks in 32 provinces, leading to the death of more than 291 security force personnel and injuries to at least 550 others. The Taliban’s spokesman in Afghanistan, Zabihullah Mujahid, claimed the latest government figures were inflated to deter intra-Afghan peace talks. -

Reporting Period

Reporting Period: 10 April to 16 April 2014 Donor: OFDA/USAID Submission Date: 16 April 2014 Incidents Update: During the reporting period four natural disaster incidents were reported. Central Region: Kapisa Province (Update): The preliminary information obtained from ANDMA on 7 April indicates, around 400 families being affected as result of continuous rainfall in Hisa-i-Awali Kohistan, Hisa-i-Duwumi Kohistan, Koh Band, Nijrab, Mahmudi Raqi and Tagab districts. Joint assessment teams comprised of IOM, CARE, ANDMA, DRC and WFP/AREA initiated assessment of the affected areas 10-13 April, 47 families were verified in in need of NFIs, emergency shelter and food items. IOM will distribute family revitalization, blanket and shelter modules while DRC committed to provide Kapisa, Koh Band district, Aram Kot village, 10 April 2014, IOM cash assistance. Eastern Region: Nuristan Province (Update): As per initial information obtained from ARCS on 7 April, six families were reportedly affected as a result of a landslide in Parun district (Sosam village). A joint assessment team consisted of ARCS, IMC and WFP initiated assessment on 8 April, six families were verified in need of NFIs and food items. ARCS, IMC and WFP will cover NFIs and food needs. Northeast Region: Takhar Province: As per the initial information from ANDMA, on 12 April, 118 families were displaced as a result of landslide in Rustaq district (Khowja Khairab village). The incident resulted in destruction of the houses, household items and the families were forced to evacuate the area. A joint assessment team comprised of WFP, ANDMA, ARCS and CONCERN assessed the area on 12 April.