Buddhist Images

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mahamayuri Vidyarajni Sadhana” E‐Book

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Padmakumara website would like to gratefully acknowledge the following individuals for contributing to the production of “Mahamayuri Vidyarajni Sadhana” e‐book. Translator: Alice Yang, Zhiwei Editor: Jason Yu Proofreader: Renée Cordsen, Jackie Ho E‐book Designer: Alice Yang, Ernest Fung The Padmakumara website is most grateful to Living Buddha Lian‐sheng for transmitting such precious dharma. May Living Buddha Lian‐sheng always be healthy and continue to teach and liberate beings in samsara. May all sentient beings quickly attain Buddhahood. Om Guru Lian‐Sheng Siddhi Hum. Exhaustive research was undertaken to ensure the content in this e‐book is accurate, current and comprehensive at publication time. However, due to differing individual interpreting skills and language differences among translators and editors, we cannot be responsible for any minor wording discrepancies or inaccuracies. In addition, we cannot be responsible for any damage or loss which may result from the use of the information in this e‐book. The information given in this e‐book is not intended to act as a substitute for the actual lineage and transmission empowerments from H.H. Living Buddha Lian‐sheng or any authorized True Buddha School master. If you wish to contact the author or would like more information about the True Buddha School, please write to the author in care of True Buddha Quarter. The author appreciates hearing from you and learning of your enjoyment of this e‐book and how it has helped you. We cannot guarantee that every letter written to the author can be answered, but all will be forwarded. -

English Index of Taishō Zuzō

APPENDIX 2: TEXTS CITED FROM THE TZ. TZ. (Taisho Zuzobu) is the iconographic section of the Taisho edition of the Chinese Tripitaka. The serial numbers of the Hobogirin are given in brackets. Volume 1 1. (2921) Hizoki ‘Record kept secretly’: 1. Kukai (774-835). 2. Mombi (8th cent.). 2. (2922) Daihi-taizd-futsu-daimandara-chu - Shoson-shuji-kyoji-gydso-shoi-shosetsu-fudoki ‘Observations on the bljas, symbols, forms, and disposition of the deities in the Garbhadhatu-mandala’, by Shinjaku (886-927). 3. (2923) Taizo-mandara-shichijushi-mon ‘Seventy-four questions on the Garbhadhatu’, by Shinjaku (886-927). 4. (2924) Ishiyama-shichi-shu ‘Collection of seven items at Ishiyama’, by Junnyu (890-953). The seven items are: Sanskrit name, esoteric name, blja, samaya symbol, mudra, mantra and figure. 5. (2925) Kongokai-shichi-shu ‘Collection of seven items of the Vajradhatu’, by Junnyu (890-953). 6. (2926) Madara-shd ‘Extract from mandala’, by Ninkai (955-1046). No illustration. 7. (2927) Taizo-sambu-ki ‘Note on three families of the Garbhadhatu’ by Shingo (934-1004). 8. (2928) Taiz5-yogi ‘Essential meaning of the Garbhadhatu’, by Jojin (active in 1108). No illustration. 9. (2929) Ryobu-mandara-taiben-sho ‘Comparison of the pair of mandalas’, by Saisen (1025-1115). No illustration. 10. (2930) Taizokai-shiju-mandara-ryaku-mo ndo ‘Dialogue on the fourfold enclosures of the Garbhadhatu’, by Saisen (1025-1115). No illustration. 11. (2931) Kue-hiyo-sho ‘Extract of the essentials of the nine mandalas’, author unknown. 12. (2932) Ryobu-mandara-kudoku-ryakusho ‘Extract on the merit of the pair of mandalas’, by Kakuban (1095-1143). -

LỊCH SỬ PHẬT VÀ BỒ TÁT (Phan Thượng Hải)

LỊCH SỬ PHẬT VÀ BỒ TÁT (Phan Thượng Hải) Lịch sử Phật Giáo bắt đầu ở Ấn Độ. Từ Phật Giáo Nguyên Thủy sinh ra Phật Giáo Đại Thừa. Đại Thừa gọi Phật Giáo Nguyên Thủy là Tiểu Thừa. Sau đó Bí Mật Phật Giáo (Mật Giáo) thành lập nên Đại Thừa còn được gọi là Hiển Giáo. Mật Giáo truyền sang Trung Quốc lập ra Mật Tông và sau đó truyền sang Nhật Bản là Chơn Ngôn Tông (Chân Ngôn Tông). Mật Giáo cũng truyền sang Tây Tạng thành ra Kim Cang Thừa. Ngày nay những Tông Thừa nầy tồn tại trong Phật Giáo khắp toàn thế giới. Từ vị Phật có thật trong lịch sử là Thích Ca Mâu Ni Phật, chư Phật và chư Bồ Tát cũng có lịch sử qua kinh điển và triết lý của Tông Thừa Phật Giáo. Bố Cục Phật Giáo Nguyên Thủy Thích Ca Mâu Ni Phật (trang 2) Nhân Gian Phật (Manushi Buddha) (trang 7) Đại Thừa Tam Thế Phật (trang 7) Bồ Tát (trang 11) Quan Tự Tại - Quan Thế Âm (Avalokiteshvara) (trang 18) Tam Thân Phật (trang 28) Báo Thân và Tịnh Độ (trang 33) A Di Đà Phật và Tịnh Độ Tông (trang 35) Bàn Thờ và Danh Hiệu (trang 38) Kim Cang Thừa Tam Thân Phật và Bồ Tát (trang 41) Thiền Na Phật (Dhyana Buddha) (trang 42) A Đề Phật (trang 45) Nhân Gian Phật (Manushi Buddha) (trang 46) Bồ Tát (trang 46) Minh Vương (trang 49) Hộ Pháp (trang 51) Hộ Thần (trang 53) Consort và Yab-Yum (trang 55) Chơn Ngôn Tông và Mật Tông (trang 57) PHẬT GIÁO NGUYÊN THỦY Phật Giáo thành lập và bắt đầu với Thích Ca Mâu Ni Phật. -

Uế Tích Kim Cương Pháp Kinh

UẾ TÍCH KIM CƯƠNG PHÁP KINH Bản cập nhật tháng 6/2014 http://kinhmatgiao.wordpress.com DẪN NHẬP Ô Sô Sa Ma Minh Vương, tên Phạn là Ucchusma, dịch âm là Ô Bộ Sắt Ma, Ô Sắt Sa Ma, Ô Sô Tháp Ma, Ô Xu Sa Ma, Ô Sô Sắt Ma...Dịch ý là : Bất Tịnh Khiết, Trừ Uế, thiêu đốt Uế Ác... Lại có tên là: Ô Mục Sa Ma Minh Vương, Ô Xu Sáp Ma Minh Vương, Ô Tố Sa Ma Minh Vương. Cũng gọi là Uế Tích Kim Cương, Hỏa Đầu Kim Cương, Bất Tịnh Kim Cương, Thụ Xúc Kim Cương, Bất Hoại Kim Cương, Trừ Uế Phẫn Nộ Tôn…. Trong Ấn Độ Giáo, từ ngữ UCCHUṢMA nhằm chỉ vị Thần Lửa AGNI với ý nghĩa “Làm cho tiếng lửa kêu lốp bốp” Trong Phật Giáo, UCCHUṢMA là một trong các Tôn phẫn nộ được an trí trong viện chùa của Thiền Tông và Mật Giáo. Riêng Mật Giáo thì xem Ucchuṣma là Vị Kim Cương biểu hiện cho Giáo Lệnh Luân Thân (Ādeśana-cakra-kāya) của Yết Ma Bộ (Karma-kulāya: Nghiệp Dụng Bộ) thuộc phương Bắc cùng với Kim Cương Dạ Xoa (Vajra-yakṣa) cũng là Giáo Lệnh Luân Thân (Ādeśana-cakra-kāya) của Đức Bất Không Thành Tựu Như Lai (Amogha-siddhi tathāgata) có Luân đồng thể và khác thể. Nói về đồng Thể thì hai Tôn này đều là Thân Đại Phẫn Nộ nhằm giáo hóa các chúng sinh khó độ. Đây là phương tiện thi hành hạnh “chuyển mọi việc của Thế Gian thành phương tiện giải thoát” biểu hiện cho Đại Nguyện thuần khiết của Đức Phật Thích Ca Mâu Ni (Śākyamuṇi-buddha) là “Rời bỏ quốc thổ thanh tịnh đi vào cõi ô uế nhiễm trược để thành tựu sự hóa độ các chúng sinh ngang ngược độc ác khó giáo hóa”. -

Déités Bouddhiques

Michel MATHIEU-COLAS www.mathieu-colas.fr/michel LES DÉITÉS BOUDDHIQUES Les divinités bouddhiques posent des problèmes spécifiques, comme en témoigne le terme « déité » souvent utilisé à leur propos. Il faut rappeler, en premier lieu, que le bouddhisme ancien ( Hinay āna ou Therav āda 1) ne reconnaît aucun dieu. Le Bouddha historique auquel il se réfère (Siddhartha Gautama Shakyamuni) n’est pas une divinité, mais un sage, un maître qui a montré la voie vers la libération du sams āra (le cycle des renaissances) et l’accès au nirv āna . Tout au plus reconnaît-on, à ce stade, l’existence de Bouddhas antérieurs (les « Bouddhas du passé », à l’exemple de Dipankara), tout en en annonçant d’autres pour l’avenir (le ou les « Bouddha[s] du futur », cf. Maitreya). Nous les mentionnons dans le dictionnaire, mais il ne faut pas oublier leur statut particulier. La situation change avec le bouddhisme Mah āyāna (le « Grand Véhicule », apparu aux alentours de notre ère). Il est vrai que, dans l’ouvrage le plus connu ( Saddharma-Pundar īka , le « Lotus de la bonne Loi »), le Bouddha historique garde encore la première place, même s’il est entouré de milliers de bouddhas et de bodhisattvas. Mais bientôt apparaît un panthéon hiérarchisé constitué de divinités clairement identifiées – le Bouddha primordial ( Adi Bouddha ), les cinq « bouddhas de la méditation » ( Dhyani Bouddhas ), les cinq « bodhisattvas de la méditation » (Dhyani Bodhisattvas ). Les « bouddhas humains » ( Manushi Bouddhas ), dont Shakyamuni, ne sont que des émanations des véritables déités. 1 Les deux termes sont souvent employés l’un pour l’autre pour désigner le bouddhisme ancien. -

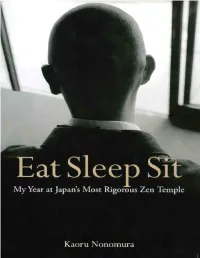

Eat Sleep Sit: My Year at Japan's Most Rigorous Zen Temple

Eat Sleep Sit Eat Sleep Sit My Year at Japan’s Most Rigorous Zen Temple Kaoru Nonomura Translated by Juliet Winters Carpenter KODANSHA INTERNATIONAL Tokyo • New York • London Originally published by Shinchosha, Tokyo, in 1996, under the title Ku neru suwaru: Eiheiji shugyoki. Distributed in the United States by Kodansha America LLC, and in the United Kingdom and continental Europe by Kodansha Europe Ltd. Published by Kodansha International Ltd., 17–14, Otowa 1- chome, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo, 112–8652. Copyright ©1996 by Kaoru Nonomura. All rights reserved. Printed in Japan. ISBN 978–4–7700–3075–7 First edition, 2008 15 14 13 12 11 10 09 08 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Nonomura, Kaoru, 1959- [Ku neru suwaru. English] Eat sleep sit : my year at Japan's most rigorous zen temple / Kaoru Nonomura ; translated by Juliet Winters Carpenter. -- 1st ed. p. cm. ISBN 978-4-7700-3075-7 1. Monastic and religious life (Zen Buddhism)--Japan-- Eiheiji-cho. 2. Spiritual life--Sotoshu. 3. Eiheiji. 4. Nono- mura, Kaoru, 1959- 5. Spiritual biography--Japan. I. Title. BQ9444.4.J32E34 2008 294.3'675092--dc22 [B] 2008040875 www.kodansha-intl.com CONTENTS PART ONE The End and the Beginning Resolve Jizo Cloister Dragon Gate Main Gate Temporary Quarters Lavatory Facing the Wall Buddha Bowl Evening Service Evening Meal Night Sitting PART TWO Etiquette Is Zen Morning Service Morning Meal Cleaning the Corridors Dignified Dress Washing the Face Verses Noon Stick PART THREE Alone in the Freezing Dark Entering the Hall Monks’ Hall -

Kuan Yin Cultivation Booklet.Pdf

Kuan Yin Cultivation Booklet 1. Recite the Purification Mantras Bring your hands together and recite the following: Purification of Speech: Om, syo-lee syo-lee, ma-ha syo-lee, syo-syo-lee, so-ha Purification of Body: Om, syo-do-lee, syo-do-lee, syo-mo-lee, syo-mo-lee, so-ha. Purification of Mind: Om, fo ri la dam, ho ho hum Calling upon the local earth deity to guard the premises: Namo sam-man-do, moo-toh-nam, om, do-lo do-lo de-wei, so-ha 2. Recite the Invocation Mantra Om ah hum, so ha. (3 times) Homage to Amitabha Buddha of the Western Paradise Homage to Kuan Yin Bodhisattva Homage to the Thousand-Hand Thousand-Eye Kuan Yin Bodhisattva Homage to Maha Cundi Bodhisattva Homage to Ucchusma Homage to Acala Homage to the Four Region Heaven Celestial Vajra Protectors Homage to Padmasambhava Homage to Skanda, the Revered Dharma Protector Homage to the Revered Temple Guardian Homage to the Golden Mother of the Primordial Pond The Lord of Deities Taoist God of Heaven Taoist Master of Purity Supreme Lady of the Nine Heavens The Annual Earth Guardian Homage to Medicine Buddha Homage to Ksitigarbha Bodhisattva Homage to Jambhala Homage to Padmakumara The Great Brahma All Buddhas of the ten directions throughout the past, present and future; all Bodhisattvas and Mahasattvas. 2 Homage to Maha Prajna Paramita 3. The Great Homage Homage to the Buddhas of the Ten Directions Visualise the Root Guru appearing in the space before and above you. The ancient lineage masters, the eight personal deities, all Buddha’s of the ten directions throughout the past, present and future, all the great Bodhisattvas, Vajra Protectors and Nagas covering the space like innumerable stars. -

The Practice Involving the Ucchuṣmas (Atharvavedapariśiṣṭa 36) Peter Bisschop, Arlo Griffiths

The Practice Involving the Ucchuṣmas (Atharvavedapariśiṣṭa 36) Peter Bisschop, Arlo Griffiths To cite this version: Peter Bisschop, Arlo Griffiths. The Practice Involving the Ucchuṣmas (Atharvavedapariśiṣṭa 36). Zeitschrift für Indologie und Südasienstudien, Hempen Verlag, 2007, 24, pp.1-46. halshs-01908883 HAL Id: halshs-01908883 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01908883 Submitted on 30 Oct 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Peter Bisschop & Arlo Griffiths The Practice involving the Ucchuṣmas (Atharvavedapariśiṣṭa 36 )* Introduction In our recent study of the Pāśupata Observance (Atharvavedapariśiṣṭa 40), we expressed the intention to bring out further studies of texts from the cor- pus of Pariśiṣṭas of the Atharvaveda, especially such as throw light on the cult of Rudra-Śiva. The Pāśupatavrata showed interesting interconnections between Atharvavedic ritualism and the Śaiva Atimārga. In the present study, we focus on the so-called Ucchuṣmakalpa, transmitted as the thirty-sixth Pariśiṣṭa of the corpus, a text which takes us squarely onto the path of Tantric practices. We intend to continue our studies in the Atharvavedapariśiṣṭas with articles to appear over the coming years, one of which is likely to be devoted to the Koṭihoma, as previously announced. -

True Buddha School Practice Book

TRUE BUDDHA SCHOOL PRACTICE BOOK. (CHÂN PHẬT TÔNG ĐỒNG TU PHÁP BẢN) Truyền dạy bởi HOẠT PHẬT LIÊN SINH (Dịch giả phần Việt ngữ: Nguyễn văn Hải, M.A.) MỤC LỤC. _ Sơ lược tiểu sử của HOẠT PHẬT LIÊN SINH (About Living Buddha LIAN- SHENG) _ Cách thức qui y HOẠT PHẬT LIÊN SINH (Disclaimer) _ Lư hương tán (Incense Praise) _ Thanh tịnh tán (Pure Dharma Body Buddha) _ KIM CƯƠNG TÂM BỒ TÁT PHÁP (bốn phương pháp khởi đầu cần thiết)(Vajrasattva Practice (of the Four Premilinary Practices) _ LIÊN HOA ĐỒNG TỬ CĂN BẢN THƯỢNG SƯ TƯƠNG ỨNG PHÁP (Root Guru –Padmakumaru- Yoga) _ A DI ĐÀ PHẬT BẢN TÔN KINH (Amitabha Buddha Personal Deity Yoga) _ QUAN THẾ ÂM BỒ TÁT BẢN TÔN KINH (Avalokitesvara Buddha Personal Deity Yoga) _ ĐỊA TẠNG VƯƠNG BỒ TÁT BẢN TÔN KINH (Ksitigarbha Bodhisattva Personal Deity Yoga) _ ĐẠI CHUẨN ĐỀ PHẬT MẪU BẢN TÔN KINH (Maha Cundi Bodhisattva Personal Deity Yoga) _ HOÀNG TÀI THẦN BẢN TÔN KINH (Yellow Jambhala Personal Deity Yoga) _ LIÊN HOA SINH ĐẠI SĨ BẢN TÔN KINH (Padmasambhava Personal Deity Yoga) _ DƯỢC SƯ LƯU LI QUANG VƯƠNG PHẬT BẢN TÔN KINH (Lapis Lazuli Light Medicine Buddha Personal Deity Yoga) _ ĐẠI BI CHÚ (Great Compassion Dharani) _ CHÂN PHẬT KINH (The True Buddha Sutra) _ A DI ĐÀ ĐÀ PHẬT KINH (Amitabha Sutra) _ DIÊU TRÌ KIM MẪU ĐỊNH TUỆ GIẢI THOÁT CHÂN KINH (Yao Chi Jin Mu Ding Hui Jie Tuo Zhen Jing) _ PHẬT ĐỈNH TÔN THẮNG ĐÀ LA NI CHÚ (Fo Ding Zhun Sheng Tuo Luo Ni Zhou) 1 SƠ LƯỢC TIỂU SỬ CỦA HOẠT PHẬT LIÊN SINH. -

Abhiyoga Jain Gods

A babylonian goddess of the moon A-a mesopotamian sun goddess A’as hittite god of wisdom Aabit egyptian goddess of song Aakuluujjusi inuit creator goddess Aasith egyptian goddess of the hunt Aataentsic iriquois goddess Aatxe basque bull god Ab Kin Xoc mayan god of war Aba Khatun Baikal siberian goddess of the sea Abaangui guarani god Abaasy yakut underworld gods Abandinus romano-celtic god Abarta irish god Abeguwo melansian rain goddess Abellio gallic tree god Abeona roman goddess of passage Abere melanisian goddess of evil Abgal arabian god Abhijit hindu goddess of fortune Abhijnaraja tibetan physician god Abhimukhi buddhist goddess Abhiyoga jain gods Abonba romano-celtic forest goddess Abonsam west african malicious god Abora polynesian supreme god Abowie west african god Abu sumerian vegetation god Abuk dinkan goddess of women and gardens Abundantia roman fertility goddess Anzu mesopotamian god of deep water Ac Yanto mayan god of white men Acacila peruvian weather god Acala buddhist goddess Acan mayan god of wine Acat mayan god of tattoo artists Acaviser etruscan goddess Acca Larentia roman mother goddess Acchupta jain goddess of learning Accasbel irish god of wine Acco greek goddess of evil Achiyalatopa zuni monster god Acolmitztli aztec god of the underworld Acolnahuacatl aztec god of the underworld Adad mesopotamian weather god Adamas gnostic christian creator god Adekagagwaa iroquois god Adeona roman goddess of passage Adhimukticarya buddhist goddess Adhimuktivasita buddhist goddess Adibuddha buddhist god Adidharma buddhist goddess -

University of Hawai'i Library

UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I LIBRARY THE FOUR SAINTS INTERCULTURAL EXCHANGE AND THE EVOLUTION OF THEIR ICONOGRAPHY A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAW AI'I IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN RELIGION (ASIAN) AUGUST 2008 By Ryan B. Brooks Thesis Committee: Poul Andersen, Chairperson Helen Baroni Edward Davis We certify that we have read this thesis and that, in our opinion, it is satisfactory in scope and quality as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts in Religion (Asian). THESIS COMMITTEE ii Copyright © 2008 by Ryan Bruce Brooks All rights reserved. iii Acknowledgments I would like to thank the members of my thesis committee-Poul Andersen, Helen Baroni, and Edward Davis-------for their ongoing support and patience in this long distance endeavor. Extra thanks are due to Poul Andersen for his suggestions regarding the history and iconography ofYisheng and Zhenwu, as well as his help with translation. I would also like to thank Faye Riga for helping me navigate the formalities involved in this process. To the members of my new family, Pete and Jane Dahlin, lowe my most sincere gratitude. Without their help and hospitality, this project would have never seen the light of day. Finally, and most importantly, I would like to thank my wife Nicole and son Eden for putting up with my prolonged schedule, and for inspiring me everyday to do my best. iv Abstract Images of the Four Saints, a group ofDaoist deities popular in the Song period, survive in a Buddhist context and display elements of Buddhist iconography. -

The True Buddha Money Tree Practice

The True Buddha Money Tree Practice His Holiness Living Buddha Lian-sheng, Sheng-yen Lu True Buddha Practice Book | www.Padmakumara.org ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Practice Translation Team of the Padmakumara Forum would like to gratefully acknowledge the following individuals for contributing to the production of “The True Buddha Money Tree Practice” e-book. Translator: Imelda Tan Editor: Jacqueline Ho E-book Director and Producer: Imelda Tan The Practice Translation Team of the Padmakumara Forum is most grateful to Grand Master Lu for transmitting such precious Dharma. May Grand Master Lu always be healthy and continue to teach and liberate beings in Samsara. May all sentient beings quickly attain Buddhahood. Om Guru Lian-Sheng Siddhi Hum. Exhaustive research was undertaken to ensure the content in this e-book is accurate, current and comprehensive at publication time. However, due to differing individual interpreting skills and language differences among translators and editors, we cannot be responsible for any minor wording discrepancies or inaccuracies. In addition, we cannot be responsible for any damage or loss which may result from the use of the information in this e-book. The information given in this e-book is not intended to act as a substitute for the actual lineage and transmission empowerments from H.H. Living Buddha Lian-sheng, Sheng-yen Lu or any authorized True Buddha Master. For further information, please see page 5. If you wish to contact the author or would like more information about the True Buddha School, please write to the author in care of True Buddha Tantric Quarter. The author appreciates hearing from you and learning of your enjoyment of this e-book and how it has helped you.