Anna Maria Ortese's Il Mare Non Bagna Napoli

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Creatureliness

Thinking Italian Animals Human and Posthuman in Modern Italian Literature and Film Edited by Deborah Amberson and Elena Past Contents Acknowledgments xi Foreword: Mimesis: The Heterospecific as Ontopoietic Epiphany xiii Roberto Marchesini Introduction: Thinking Italian Animals 1 Deborah Amberson and Elena Past Part 1 Ontologies and Thresholds 1 Confronting the Specter of Animality: Tozzi and the Uncanny Animal of Modernism 21 Deborah Amberson 2 Cesare Pavese, Posthumanism, and the Maternal Symbolic 39 Elizabeth Leake 3 Montale’s Animals: Rhetorical Props or Metaphysical Kin? 57 Gregory Pell 4 The Word Made Animal Flesh: Tommaso Landolfi’s Bestiary 75 Simone Castaldi 5 Animal Metaphors, Biopolitics, and the Animal Question: Mario Luzi, Giorgio Agamben, and the Human– Animal Divide 93 Matteo Gilebbi Part 2 Biopolitics and Historical Crisis 6 Creatureliness and Posthumanism in Liliana Cavani’s The Night Porter and Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Salò 111 Alexandra Hills 7 Elsa Morante at the Biopolitical Turn: Becoming- Woman, Becoming- Animal, Becoming- Imperceptible 129 Giuseppina Mecchia x CONTENTS 8 Foreshadowing the Posthuman: Hybridization, Apocalypse, and Renewal in Paolo Volponi 145 Daniele Fioretti 9 The Postapocalyptic Cookbook: Animality, Posthumanism, and Meat in Laura Pugno and Wu Ming 159 Valentina Fulginiti Part 3 Ecologies and Hybridizations 10 The Monstrous Meal: Flesh Consumption and Resistance in the European Gothic 179 David Del Principe 11 Contemporaneità and Ecological Thinking in Carlo Levi’s Writing 197 Giovanna Faleschini -

Librib 501200.Pdf

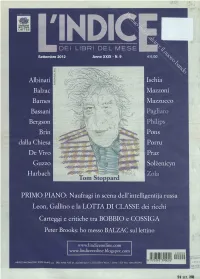

FONDAZIONE BOTTARI LATTES Settembre 2012 Anno XXIX - N. 9 Albinati Ischia Balzac Mazzoni Barnes Mazzucco Bassani Bergson Brin Pons dalla Chiesa Porru De Vivo Praz Guzzo Solzenicyn Harbach PRIMO PIANO: Naufragi in scena del?intelligenti)a russa Leon, Gallino e la LOTTA DI CLASSE dei ricchi Carteggi e critiche tra BOBBIO e COSSIGA Peter Brooks: ho messo BALZAC sul lettino www.lindiceonline.com www.lindiceonline.blogspot.com MENSILE D'INFORMAZIONE - POSTE ITALIANE s.p.a. - SPED. IN ABB. POST. D.L. 353/2003 (conv.in L. 27/02/2004 n° 46) art. I, comma ], DCB Torino - ISSN 0393-3903 Editoria La verità è destabilizzante Per Achille Erba di Lorenzo Fazio Quando è mancato Achille Erba, uno dei fon- ferimento costante al Vaticano II e all'episcopa- a domanda è: "Ma ci quere- spezzarne il meccanismo di pro- datori de "L'Indice", alcune persone a lui vicine to di Michele Pellegrino) sono ampiamente illu- Lleranno?". Domanda sba- duzione e trovare (provare) al- hanno deciso di chiedere ospitalità a quello che lui strate nel sito www.lindiceonline.com. gliata per un editore che si pre- tre verità. Come editore di libri, ha continuato a considerare Usuo giornale - anche È opportuna una premessa. Riteniamo si sarà figge il solo scopo di raccontare opera su tempi lunghi e incrocia quando ha abbandonato l'insegnamento universi- tutti d'accordo che le analisi e le discussioni vol- la verità. Sembra semplice, ep- passato e presente avendo una tario per i barrios di Santiago del Cile e, successi- te ad illustrare e approfondire nei suoi diversi pure tutta la complessità del la- prospettiva anche storica e più vamente, per una vita concentrata sulla ricerca - aspetti la ricerca storica di Achille e ad indivi- voro di un editore di saggistica libera rispetto a quella dei me- allo scopo di convocare un'incontro che ha lo sco- duare gli orientamenti generali che ad essa si col- di attualità sta dentro questa pa- dia, che sono quotidianamente po di ricordarlo, ma anche di avviare una riflessio- legano e che eventualmente la ispirano non pos- rola. -

Melodrama Or Metafiction? Elena Ferrante's Neapolitan Novels

This is a repository copy of Melodrama or metafiction? Elena Ferrante's Neapolitan Novels. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/126344/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Santovetti, O (2018) Melodrama or metafiction? Elena Ferrante's Neapolitan Novels. Modern Language Review, 113 (3). pp. 527-545. ISSN 0026-7937 https://doi.org/10.5699/modelangrevi.113.3.0527 (c) 2018 Modern Humanities Research Association. This is an author produced version of a paper published in Modern Language Review. Uploaded in accordance with the publisher's self-archiving policy. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Melodrama or metafiction? Elena Ferrante's Neapolitan Novels Abstract The fusion of high and low art which characterises Ferrante's Neapolitan Novels is one of the reasons for her global success. This article goes beyond this formulation to explore the sources of Ferrante's narrative: the 'low' sources are considered in the light of Peter Brooks' definition of the melodramatic mode; the 'high' component is identified in the self-reflexive, metafictional strategies of the antinovel tradition. -

Heteroglossia N

n. 14 eum x quaderni Andrea Rondini Heteroglossia n. 14| 2016 pianeta non-fiction a cura di Andrea Rondini heteroglossia Heteroglossia Quaderni di Linguaggi e Interdisciplinarità. eum edizioni università di macerata > 2006-2016 Dipartimento di Scienze Politiche, della Comunicazione e delle Relazioni Internazionali. isbn 978-88-6056-487-0 edizioni università di macerata eum x quaderni n. 14 | anno 2016 eum eum Heteroglossia n. 14 Pianeta non-fiction a cura di Andrea Rondini eum Università degli Studi di Macerata Heteroglossia n. 14 Quaderni di Linguaggi e Interdisciplinarità. Dipartimento di Scienze Politiche, della Comunicazione e delle Relazioni Internazionali Direttore: Hans-Georg Grüning Comitato scientifico: Mathilde Anquetil (segreteria di redazione), Alessia Bertolazzi, Ramona Bongelli, Ronald Car, Giorgio Cipolletta, Lucia D'Ambrosi, Armando Francesconi, Hans- Georg Grüning, Danielle Lévy, Natascia Mattucci, Andrea Rondini, Marcello Verdenelli, Francesca Vitrone Comitato di redazione: Mathilde Anquetil (Università di Macerata), Alessia Bertolazzi (Università di Macerata), Ramona Bongelli (Università di Macerata), Edith Cognigni (Università di Macerata), Lucia D'Ambrosi (Università di Macerata), Lisa Block de Behar (Universidad de la Republica, Montevideo, Uruguay), Madalina Florescu (Universidade do Porto, Portogallo), Armando Francesconi (Università di Macerata), Aline Gohard-Radenkovic (Université de Fribourg, Suisse), Karl Alfons Knauth (Ruhr-Universität Bochum), Claire Kramsch (University of California Berkeley), Hans-Georg -

Heteroglossia N

n. 14 eum x quaderni Andrea Rondini Heteroglossia n. 14| 2016 pianeta non-fiction a cura di Andrea Rondini heteroglossia Heteroglossia Quaderni di Linguaggi e Interdisciplinarità. eum edizioni università di macerata > 2006-2016 Dipartimento di Scienze Politiche, della Comunicazione e delle Relazioni Internazionali. isbn 978-88-6056-487-0 edizioni università di macerata eum x quaderni n. 14 | anno 2016 eum eum Heteroglossia n. 14 Pianeta non-fiction a cura di Andrea Rondini eum Università degli Studi di Macerata Heteroglossia n. 14 Quaderni di Linguaggi e Interdisciplinarità. Dipartimento di Scienze Politiche, della Comunicazione e delle Relazioni Internazionali Direttore: Hans-Georg Grüning Comitato scientifico: Mathilde Anquetil (segreteria di redazione), Alessia Bertolazzi, Ramona Bongelli, Ronald Car, Giorgio Cipolletta, Lucia D'Ambrosi, Armando Francesconi, Hans- Georg Grüning, Danielle Lévy, Natascia Mattucci, Andrea Rondini, Marcello Verdenelli, Francesca Vitrone Comitato di redazione: Mathilde Anquetil (Università di Macerata), Alessia Bertolazzi (Università di Macerata), Ramona Bongelli (Università di Macerata), Edith Cognigni (Università di Macerata), Lucia D'Ambrosi (Università di Macerata), Lisa Block de Behar (Universidad de la Republica, Montevideo, Uruguay), Madalina Florescu (Universidade do Porto, Portogallo), Armando Francesconi (Università di Macerata), Aline Gohard-Radenkovic (Université de Fribourg, Suisse), Karl Alfons Knauth (Ruhr-Universität Bochum), Claire Kramsch (University of California Berkeley), Hans-Georg -

William Weaver Papers, 1977-1984

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt4779q44t No online items Finding Aid for the William Weaver Papers, 1977-1984 Processed by Lilace Hatayama; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé and edited by Josh Fiala. UCLA Library, Department of Special Collections Manuscripts Division Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.library.ucla.edu/libraries/special/scweb/ © 2005 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid for the William 2094 1 Weaver Papers, 1977-1984 Descriptive Summary Title: William Weaver Papers Date (inclusive): 1977-1984 Collection number: 2094 Creator: Weaver, William, 1923- Extent: 2 boxes (1 linear ft.) Abstract: William Weaver (b.1923) was a free-lance writer, translator, music critic, associate editor of Collier's magazine, Italian correspondent for the Financial times (London), music and opera critic in Italy for the International herald tribune, and record critic for Panorama. The collection consists of Weaver's translations from Italian to English, including typescript manuscripts, photocopied manuscripts, galley and page proofs. Repository: University of California, Los Angeles. Library. Department of Special Collections. Los Angeles, California 90095-1575 Physical location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact the UCLA Library, Department of Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Access COLLECTION STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF: Advance notice required for access. Restrictions on Use and Reproduction Property rights to the physical object belong to the UCLA Library, Department of Special Collections. -

978–0–230–30016–3 Copyrighted Material – 978–0–230–30016–3

Copyrighted material – 978–0–230–30016–3 Introduction, selection and editorial matter © Louis Bayman and Sergio Rigoletto 2013 Individual chapters © Contributors 2013 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No portion of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, Saffron House, 6–10 Kirby Street, London EC1N 8TS. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The authors have asserted their rights to be identified as the authors of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published 2013 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN Palgrave Macmillan in the UK is an imprint of Macmillan Publishers Limited, registered in England, company number 785998, of Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS. Palgrave Macmillan in the US is a division of St Martin’s Press LLC, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010. Palgrave Macmillan is the global academic imprint of the above companies and has companies and representatives throughout the world. Palgrave® and Macmillan® are registered trademarks in the United States, the United Kingdom, Europe and other countries. ISBN 978–0–230–30016–3 This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. Logging, pulping and manufacturing processes are expected to conform to the environmental regulations of the country of origin. -

2011 – Cincinnati, OH

Society for American Music Thirty-Seventh Annual Conference International Association for the Study of Popular Music, U.S. Branch Time Keeps On Slipping: Popular Music Histories Hosted by the College-Conservatory of Music University of Cincinnati Hilton Cincinnati Netherland Plaza 9–13 March 2011 Cincinnati, Ohio Mission of the Society for American Music he mission of the Society for American Music Tis to stimulate the appreciation, performance, creation, and study of American musics of all eras and in all their diversity, including the full range of activities and institutions associated with these musics throughout the world. ounded and first named in honor of Oscar Sonneck (1873–1928), early Chief of the Library of Congress Music Division and the F pioneer scholar of American music, the Society for American Music is a constituent member of the American Council of Learned Societies. It is designated as a tax-exempt organization, 501(c)(3), by the Internal Revenue Service. Conferences held each year in the early spring give members the opportunity to share information and ideas, to hear performances, and to enjoy the company of others with similar interests. The Society publishes three periodicals. The Journal of the Society for American Music, a quarterly journal, is published for the Society by Cambridge University Press. Contents are chosen through review by a distinguished editorial advisory board representing the many subjects and professions within the field of American music.The Society for American Music Bulletin is published three times yearly and provides a timely and informal means by which members communicate with each other. The annual Directory provides a list of members, their postal and email addresses, and telephone and fax numbers. -

Raffaele La Capria È Nato a Napoli Nel 1922, Dove Si È Laureato in Giurisprudenza

Raffaele La Capria è nato a Napoli nel 1922, dove si è laureato in Giurisprudenza. Ha compiuto la sua formazione letteraria soggiornando in Francia, Inghilterra e Stati Uniti. Narratore e saggista, ha collaborato con riviste e quotidiani, tra cui "Il Mondo", "Tempo presente" e il "Corriere della Sera" ed è stato autore di radiodrammi per la Rai. È stato co-sceneggiatore di molti film di Francesco Rosi, tra i quali Le mani sulla città (1963), Uomini contro (1970). Ha esordito con il romanzo Un giorno d'impazienza (1952). Nel 1961 ha vinto il premio Strega con Ferito a morte, ritratto di Napoli che "ti ferisce a morte o t'addormenta", e di una generazione seguita con complessi sbalzi temporali lungo l'arco di un decennio.Nel 1982 ha raccolto i tre romanzi Un giorno d'impazienza, Ferito a morte e Amore e psiche (1973) nel volume Tre romanzi di una giornata. In seguito si è dedicato, con l'eccezione di Fiori giapponesi (1979) e La neve del Vesuvio (1988), a un genere che, anche se con una forte vena narrativa, è molto più vicino alla saggistica. L'argomento di gran parte della sua letteratura è Napoli, vista quasi sempre da lontano poiché l'autore lasciò la sua città in gioventù per trasferirsi a Roma: L'occhio di Napoli del 1994 o Napolitan Graffiti del 1999 sono due esempi significativi, ai quali si aggiunge Capri e non più Capri(1991). Non mancano pagine di riflessione letteraria, o sul mestiere dello scrittore, come Letteratura e salti mortali (1990) o il libro pubblicato da Minimum fax nel 1996, L'apprendista scrittore, in cui prosegue idealmente l'abbozzo di autobiografia letteraria, che aveva cominciato con Un giorno d'impazienza. -

The Cinema of Giorgio Mangiamele

WHO IS BEHIND THE CAMERA? The cinema of Giorgio Mangiamele Silvana Tuccio Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August, 2009 School of Culture and Communication The University of Melbourne Who is behind the camera? Abstract The cinema of independent film director Giorgio Mangiamele has remained in the shadows of Australian film history since the 1960s when he produced a remarkable body of films, including the feature film Clay, which was invited to the Cannes Film Festival in 1965. This thesis explores the silence that surrounds Mangiamele’s films. His oeuvre is characterised by a specific poetic vision that worked to make tangible a social reality arising out of the impact with foreignness—a foreign society, a foreign country. This thesis analyses the concept of the foreigner as a dominant feature in the development of a cinematic language, and the extent to which the foreigner as outsider intersects with the cinematic process. Each of Giorgio Mangiamele’s films depicts a sharp and sensitive picture of the dislocated figure, the foreigner apprehending the oppressive and silencing forces that surround his being whilst dealing with a new environment; at the same time the urban landscape of inner suburban Melbourne and the natural Australian landscape are recreated in the films. As well as the international recognition given to Clay, Mangiamele’s short films The Spag and Ninety-Nine Percent won Australian Film Institute awards. Giorgio Mangiamele’s films are particularly noted for their style. This thesis explores the cinematic aesthetic, visual style and language of the films. -

Introduction: Shakespeare, Spectro-Textuality, Spectro-Mediality 1

Notes Introduction: Shakespeare, Spectro-Textuality, Spectro-Mediality 1 . “Inhabiting,” as distinct from “residing,” suggests haunting; it is an uncanny form of “residing.” See also, for instance, Derrida’s musings about the verb “to inhabit” in Monolingualism (58). For reflections on this, see especially chapter 4 in this book. 2 . Questions of survival are of course central to Derrida’s work. Derrida’s “classical” formulation of the relationship between the living-on of a text and (un)translat- ability is in Parages (147–48). See also “Des Tours” on “the necessary and impos- sible task of translation” (171) and its relation with the surviving dimension of the work (182), a reading of Walter Benjamin’s “The Task of the Translator.” In one of his posthumously published seminars, he stresses that survival—or, as he prefers to call it, “survivance”—is “neither life nor death pure and simple,” and that it is “not thinkable on the basis of the opposition between life and death” (Beast II 130). “Survivance” is a trace structure of iterability, a “living dead machine” (131). To Derrida, what is commonly called “human life” may be seen as one of the outputs of this structure that exceeds the “human.” For a cogent “posthumanist” understanding of Derrida’s work, and the notion of the trace in particular, see Wolfe. 3 . There are of course significant exceptions, and this book is indebted to these studies. Examples are Wilson; Lehmann, Shakespeare Remains ; Joughin, “Shakespeare’s Genius” and “Philosophical Shakespeares”; and Fernie, “Introduction.” Richard Burt’s work is often informed by Derrida’s writings. -

1. Sulle Tracce Di Elena Ferrante: Questioni Di Metodo E Primi Risultati

DOI: 10.13137/978-88-8303-913-3/18478 1. Sulle tracce di Elena Ferrante: questioni di metodo e primi risultati michele a. cortelazzo Università di Padova arjuna tuzzi Università di Padova Abstract This chapter illustrates the implementation of quantitative analysis methods on a corpus of modern Italian novels aimed to shed light on the identity of Elena Ferrante, the pen name of a very successful novelist whose real identity is still unknown. After a review of previous attempts conducted according to different approaches (based on lexical, contextual and thematic factors), in order to offset the impact of diatopic varieties of Italian the seven novels written by Elena Fer- rante have been compared to 39 novels written by ten authors from Campania (Ferrante’s region of origin) according to two methods: correspondence analysis and intertextual distance. Both methods show that Elena Ferrante’s novels are more similar to Domenico Starnone’s works than to the novels of any other au- thor included in the corpus. In addition, a lexical analysis shows that, compared to the other authors, Ferrante and Starnone share the greatest number of lexical items used exclusively in their novels. Conclusively, the qualitative and quantita- tive approaches used in this study confirm that a similarity emerges between the novels published by Ferrante and Starnone after the early 1990s and paves the way to further research based on larger corpora of fiction as well as non-fictional texts. Keywords Authorship attribution, computational linguistics, corpus linguistics, Elena Fer- rante, intertextual distance. 11 1. Premessa Il caso Elena Ferrante non poteva non attirare l’attenzione degli autori di questo contributo, due studiosi di estrazione diversa, una statistica e un linguista, che da anni si occupano di analisi quantitativa di dati testuali e, in particolare, della misurazione delle affinità lessicali tra testi.