How to Build a Sharpie Sailboat

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Junk Rig Glossary (JRG) Version 20 APR 2016

The Junk Rig Glossary (JRG) Version 20 APR 2016 Welcome to the Junk Rig Glossary! The Junk Rig Glossary (JRG) is a Member Project of the Junk Rig Association, initiated by Bruce Weller who, as a then new member, found that he needed a junk 'dictionary’. The aim is to create a comprehensive and fully inclusive glossary of all terms pertaining to junk rig, its implementation and characteristics. It is intended to benefit all who are interested in junk rig, its history and on-going development. A goal of the JRG Project is to encourage a standard vocabulary to assist clarity of expression and understanding. Thus, where competing terms are in common use, one has generally been selected as standard (please see Glossary Conventions: Standard Versus Non-Standard Terms, below) This is in no way intended to impugn non-standard terms or those who favour them. Standard usage is voluntary, and such designations are wide open to review and change. Where possible, terminology established by Hasler and McLeod in Practical Junk Rig has been preferred. Where innovators have developed a planform and associated rigging, their terminology for innovative features is preferred. Otherwise, standards are educed, insofar as possible, from common usage in other publications and online discussion. Your participation in JRG content is warmly welcomed. Comments, suggestions and/or corrections may be submitted to [email protected], or via related fora. Thank you for using this resource! The Editors: Dave Zeiger Bruce Weller Lesley Verbrugge Shemaya Laurel Contents Some sections are not yet completed. ∙ Common Terms ∙ Common Junk Rigs ∙ Handy references Common Acronyms Formulae and Ratios Fabric materials Rope materials ∙ ∙ Glossary Conventions Participation and Feedback Standard vs. -

The Sharpie –A Personal View 2009

The Sharpie –A Personal View 2009 THE SHARPIE - A PERSONAL VIEW BY MIKE WALLER This article was originally published in Australian Amateur Boat Builder Magazine * * * * * To say that all flat bottomed boats are Sharpies is to say that all animals with four legs are horses. The statement simply does not hold water. It is true that most sharpies have flat bottoms, but the Sharpie is a unique design style which evolved over a specific period of history to fill a particular need, and to which certain well defined rules of design apply. The initial statement also denies the individuality of a multitude of other distinct hull ‘types’ such as the many and varied dory hull forms, skiffs, punts and hunting boats, and ‘near flat bottomed’ boats such as skipjacks, (not all Sharpies have absolutely flat bottoms, for that matter,) which developed in tandem with the Sharpie. A common misconception is that the Sharpie originated in Europe. It is true that many flat bottomed boats have existed in Europe over the years, notably the ‘Metre Sharpies’, but to say that the Sharpie evolved in Europe would make such great figures as Howard Chapelle, the well known maritime historian, turn in his grave. While there will always be differing opinions, the accepted history of the traditional Sharpie as we know it, is that it evolved on the eastern seaboard of the United States of America in the Oyster fisheries of Connecticut. It is largely down to the efforts of Howard Chapelle, who spent a lifetime documenting the development of the simple working boats of the United States, that we can credit most of our current knowledge of the rules and characteristics which define the traditional Sharpie as a distinct vessel style. -

SHALLOW BOATS; DEEP ADVENTURES! Since 1984

Since 1984 SHALLOW BOATS; DEEP ADVENTURES! 1 SHOAL DRAFT STABILITY, SIMPLICITY, SPEED AND SAFETY. I’m here to talk about a belief in and a passion for shoal-draft boats, particularly the development of the Round Bottomed Sharpie. I started sailing in centreboard dinghies and that excitement has returned with these boats. As you’ll see these 2 boats have become known as Presto Boats. NEW HAVEN OYSTER- TONGING SHARPIE By definition a Sharpie is a flat-bottomed boat and a New Haven oyster-tonging sharpie looked like this. They were easy to build with their box shape & simple rigs but the boat is an ingenious piece of function and efficiency. The stern is round so the tongs don’t snag on transom corners; the freeboard is low so it’s easy to swing the tongs on board and the long centreboard trunk stops the oysters from shifting SEA OF ABACO 3 under sail. NEW HAVEN SHARPIE RIG The unstayed masts rotate through 360 degrees so the oystermen would sail to windward of the oyster beds and let the sails stream out over the bow while drifting over the beds tonging away. The sails are self-tending and self-vanged so handling is very easy. The boats are fast when loaded so you can get the oysters fresh to market. Oyster bars in big cities were the Starbucks of the late 1800s. You’d pop in for a ½ dozen as a pick-me-up. 4 On the right is an Outward Bound 30 to our design. With our contemporary Sharpies we’ve retained the principles of the traditional rig; it works as well today as it did in the 1800s. -

Development of Lightweight Sharpies in NSW 1975 to 1985

Development of Lightweight Sharpies in NSW 1975 to 1985 By Rolf Lunsmann, May 2007 The ten year period from 1975 to 1985 saw rapid and dramatic technological development in the Sharpie class. Known in 1975 as the Australian Lightweight Sharpie and firmly established as one of Australia’s most prominent and popular restricted development classes, the boats changed over that period from being exclusively plywood hulls with soft rigs to largely a fleet of full composite construction hulls with high tension, fully adjustable rigs, very similar to the boats that we see sailing today. The many individual changes and developments that led to the transformation came from the strong, competitive fleets that were sailed in all the States and Territories of Australia. Many significant developments were Crescendo VII (N35) winning the Nationals for NSW for the generated in South Australia where Robin first time in 1966 in the hands of Robert Thompson, Ian Haselgrove, the most prolific boatbuilder in the Peden and Chris Buckingham. (Photo uncredited) class, worked with the local fleet on the progressive development of glass hulled timber decked boats and in Tasmania where many of new rigging control systems emerged, but it was New South Wales that first saw much of the innovation and many of the breakthroughs in hull and spar development. The article attempts to chronicle some of those developments. The predominant thinking among top Sharpie sailors in NSW in the mid 1970s was heavily influenced by the success Mark Peelgrane had achieved in winning three consecutive National Championships between 1971 and 1973. Peelgrane had sailed a plywood boat Eleanor Rigby (N35). -

Ethnohistorical Description of Eight Villages Adjoining Cape Hatteras

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Cape Hatteras National Seashore Manteo, North Carolina Final Technical Report - Volume Two: Ethnohistorical Description of the Eight Villages Adjoining Cape Hatteras National Seashore and Interpretive Themes of History and Heritage Cultural Resources Southeast Region Final Technical Report – Volume Two: Ethnohistorical Description of the Eight Villages adjoining Cape Hatteras National Seashore and Interpretive Themes of History and Heritage November 2005 prepared for prepared by Cape Hatteras National Seashore Impact Assessment, Inc. 1401 National Park Drive 2166 Avenida de la Playa, Suite F Manteo, NC 27954 La Jolla, California 92037 in fulfillment of NPS Contract C-5038010616 About the cover: New Year’s Eve 2003 was exceptionally warm and sunny over the Mid-Atlantic states. This image from the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) instrument on the Aqua satellite shows the Atlantic coast stretching from the Chesapeake Bay of Virginia to Winyah Bay of South Carolina. Albemarle and Pamlico sounds separate the long, thin islands of the Outer Banks from mainland North Carolina. Image courtesy of NASA’s Visible Earth, a catalog of NASA images and animations of our home planet found on the internet at http://visiblearth.nasa.gov. 1. Acknowledgements We thank the staff at the Cape Hatteras National Seashore headquarters in Manteo for their helpful suggestions and support of this project, most notably Doug Stover, Steve Harrison, Toni Dufficy, Steve Ryan, and Mary Doll. The following staff of the North Carolina Division of Marine Fisheries shared maps, statistics, and illustrations: Scott Chappell, Rodney Guajardo, Trish Murphy, Don Hesselman, Dee Lupton, Alan Bianchi, and Richard Davis. -

Mid Year Newsletter August 2017 Australia Day Weekend January 2018

Mid Year Newsletter August 2017 The Inverloch Classic Wooden Dinghy Regatta The Inverloch Classic Wooden Dinghy Regatta is about displaying classic wooden sailing dinghies both on and off the water, many of which were once common but are now becoming rare. By focusing on the beauty of the wood crafting, rigging and history of these boats it is hoped people will appreciate them more fully and participate in their restoration and conservation. Over the Australia Day Weekend the Regatta also highlights aspects of Inverloch’s unique seaside history. And Moth 90th Celebration - Cavalcade of Moths In 1928 Len Morris launched Olive, a single sail 11 foot long dinghy, which became the Inverloch 11 footer, then the Moth and eventually the International Moth. In 2018 Inverloch will be celebrating the 90 anniversary of the Moth and also the contribution Len Morris made to sailing. This occasion is relevant to relevant to all Moths, their owners their skippers so we welcome all makes, types regardless of the method of construction and materials to participate in the Australia Day Regatta weekend. Australia Day Weekend January 2018 Friday 26th, Saturday 27th and Sunday 28th South Gippsland Yacht Club Commodore The Classic Wooden Dinghy Regatta at Inverloch is on again in 2018. This year it will be held over the three days of the Australia Day long weekend and if it follows the trend so far, we are expecting it to be the biggest event yet. South Gippsland Yacht Club is proud of the Regatta which has developed from an idea by club members Andrew and Marion Chapman and Wayne Smith just a few years ago, into the internationally known event of today. -

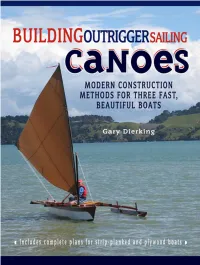

Building Outrigger Sailing Canoes

bUILDINGOUTRIGGERSAILING CANOES INTERNATIONAL MARINE / McGRAW-HILL Camden, Maine ✦ New York ✦ Chicago ✦ San Francisco ✦ Lisbon ✦ London ✦ Madrid Mexico City ✦ Milan ✦ New Delhi ✦ San Juan ✦ Seoul ✦ Singapore ✦ Sydney ✦ Toronto BUILDINGOUTRIGGERSAILING CANOES Modern Construction Methods for Three Fast, Beautiful Boats Gary Dierking Copyright © 2008 by International Marine All rights reserved. Manufactured in the United States of America. Except as permitted under the United States Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher. 0-07-159456-6 The material in this eBook also appears in the print version of this title: 0-07-148791-3. All trademarks are trademarks of their respective owners. Rather than put a trademark symbol after every occurrence of a trademarked name, we use names in an editorial fashion only, and to the benefit of the trademark owner, with no intention of infringement of the trademark. Where such designations appear in this book, they have been printed with initial caps. McGraw-Hill eBooks are available at special quantity discounts to use as premiums and sales promotions, or for use in corporate training programs. For more information, please contact George Hoare, Special Sales, at [email protected] or (212) 904-4069. TERMS OF USE This is a copyrighted work and The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. (“McGraw-Hill”) and its licensors reserve all rights in and to the work. Use of this work is subject to these terms. Except as permitted under the Copyright Act of 1976 and the right to store and retrieve one copy of the work, you may not decompile, disassemble, reverse engineer, reproduce, modify, create derivative works based upon, transmit, distribute, disseminate, sell, publish or sublicense the work or any part of it without McGraw-Hill’s prior consent. -

Transcur Forestay in This Issue

East Coast Old Gaffers Association Newsletter Aug ‘09 August 2009 Issue 80 Transcur Many readers will have heard that Transcur, area president Peter Thomas’s lovely smack, sank at her moorings on the Orwell sometime over the weekend 11th/12th July. Transcur was built in Brightlingsea in 889 and was comprehensively rebuilt by Peter over a number of years. The good news is that Transcur was quickly raised by a professional salvage team, then taken ashore at Pin Mill where a vast band of helpers, including many Dutch visitors, set to and stripped out and cleaned the interior. Miraculously, the engine restarted, but there is still an enormous amount of work to be done. However, Peter is confident she will be performing as usual in the August Classics Cruise. Transcur is probably most famous for her appearance in Frank Mulville’s book ‘Terschelling Sands’, where she was very nearly lost off the Dutch coast as a result of a navigational error. It is ironic that after 20 active years, she should succumb to something as mundane as a defective skin fitting. Forestay The sailing events so far this year have been well supported, with a number of new boats making their appearance. New faces are always welcome, but the arrival of new boats can sometimes Transcur make your committee scratch its collective head and spend time exploring the very ethos of the Old Gaffer movement. In this Issue Let me explain; the OGA was formed to ‘encourage interest in traditional gaff rig’ and to organise races for gaff rigged boats. -

Lexique De Vieille-Marine

Lettre A • de Abordage à Aviso Abordage Le terme abordage dérive du mot bord, que l'on retrouve aussi dans tribord et bâbord. Il désigne en premier lieu la collision accidentelle entre deux navires. Par extension, il s'applique également à l'assaut donné par l'équipage d'un navire à un vaisseau ennemi. Il existe, sur le plan technique, deux méthodes d'abordage : - L'abordage de franc étable s'effectue en présentant son avant au navire ennemi. Procédé d'approche rapide présentant l'inconvénient de prolonger la lutte, les assaillants ne passant qu'en petits nombres par le mât de beaupré. - L'abordage en belle, plus efficace, consiste à placer le navire attaquant bord à bord avec l'ennemi, permettant de jeter à l'assaut une équipe d'abordage beaucoup plus fournie. Aborder Accrocher un navire pour le prendre à l'abordage. Accastillage Terme dérivé de castel, désignant les châteaux qui s'élevaient aux deux extrémités des navires à voile. Par extension, c'est le nom collectif donné aux superstructures, roofs, pavois situés au-dessus du pont principal d'un navire, puis aux pièces attenantes à ces parties. Accon ou acon. • Petit bateau à fond plat qui aurait été imaginé vers 1235 par un marin irlandais, Patrice Walton. Naufragé vers la Pointe d'Escale, près du port d'Esnandes (Charente Maritime), il aurait utilisé cette embarcation pour recueillir les coquillages qui l'empêchèrent de mourir de faim. L'accon était facile à manœuvrer et utilisé comme un véritable quai mobile de chaque côté des navires mouillant en rade, à une époque où les ports étaient trop exigus pour recevoir à quai tous les navires. -

The Nautical Mind Marine Booksellers & Chart Agents

fall 2007 NAUTICAL MINbooks | charts | voyageD planning The Nautical Mind Marine Booksellers & Chart Agents 249 Queen’s Quay West Toronto, Ontario, m5j 2n5 tel: (416) 203-1163 toll free: (800) 463-9951 nauticalmind.com Contents see page 5 see page 8 see page 20 see page 14 Inside PLUS… 4 A Boater’s Dozen: 6 First Comes the Dream The Power and the Glory 1 1 Luscious Liners 5 Cruising 13 Pirates for Kids 7 Boat Design 15 Department of Guardian Angels 8 Boat Construction 16 Seamanship Never Looked So Good 9 Maintenance 18 The Big Questions 10 Electrics, Electronics & Engines 19 Knots 11 Picture & Coffee Table Books 20 Hook, Line, and Fender 12 The Great Lakes 21 Naval Exploits 13 Kids’ Books 27 Tristan Jones 14 Pirates & Sea Dogs 30 What’s New at nauticalmind.com 15 Eclectic Collection 31 Bargains at nauticalmind.com 16 Gift Ideas 19 Seamanship & Navigation 22 Calendars for 2008 It’s Easy to Order You can drop by the store, 24 Great Books at Bargain Prices phone, e-mail or order securely online. tel: (416) 203-1163 toll free: (800) 463-9951 web: nauticalmind.com Prices subject to change. email: [email protected] | tel: (416) 203-1163 | toll free: (800) 463-9951 | nautical mind The Power and the Glory A Boater’s Dozen/Cruising A BOATER’S DOZEN Here are our picks for the books—some new, some timeless—that we think best capture the force, might, and many moods of wind and sea. new Surviving the Storm: Coastal & new Beyond Endurance: 300 Boats, Offshore Tactics Sailors’ Wisdom: Day by Day 600 Miles, and One Deadly Storm by Steve & Linda Dashew by Philip Plisson by Adam Mayers Using a wealth of photos and diagrams, Master marine photographer Philip The disastrous 1979 Fastnet race is infa- the Dashews explain heavy-weather Plisson presents the sea, waves, swells, mous among sailors. -

Emma C Berry National Historic Landmark

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 EMMA C BERRY Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: EMMA C. BERRY Other Name/Site Number: 2. LOCATION Street & Number: Greenmanville Avenue Not for publication: City/Town: Mystic Vicinity: State: CT County: New London Code: Oil Zip Code: 06355 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: X Building(s):__ Public-Local:__ District:__ Public-State:__ Site: Public-Federal: Structure: X Object:_ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing ___ buildings ___ sites __ structures ___ objects Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 1 Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 EMMA C. BERRY Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service____________________________________National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this __ nomination __ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property ___ meets __ does not meet the National Register Criteria. Signature of Certifying Official Date State or Federal Agency and Bureau In my opinion, the property __ meets __ does not meet the National Register criteria. -

Good Sailing; Good Trailing Day Before in Mainly Light Winds

Kite Just Flies! With clients’ needs taking priority, it took a while before andrew Wolstenholme and Colin Henwood’s shared pocket cruiser was on the water. But making her debut at the English raid, she proved the long wait was worthwhile, writes Kathy Mansfield. With photographs by the author. ometimes there's a Eureka moment, when you realise of Henwood & Dean, decide to build a boat for themselves and something has really worked. For me, it was at the end their families. Such projects tend to fall to the bottom of the Sof July in the Solent, when I was waiting near Newtown list. Andrew had started by thinking about a pocket cruiser, Creek for boats of the first English Raid boats to arrive. I cat ketch rigged, in which they could enjoy family outings suspect that what I saw was the result of good tactics but and also participate in Raids but as he considered the options I was expecting the longer waterline boats to arrive early and the compromises that would have to be made, he ended on and at first couldn't identify the boat that was pounding up with a different set of parameters which seemed to work down towards us, flying along, pushing the spray outwards. It better for what they had in mind. sparkled. I wanted one. Then I realized it had to be Kite , the boat I’d sailed the Good sailinG; Good trailinG day before in mainly light winds. An elegant little day cruiser, The basic concept was a daysailer with a small cabin for she’d proved comfortable and easy to handle and I liked her occasional nights aboard, able to be towed by an ordinary very much.