Final Evaluation of “Progressive Control of Peste Des Petits Ruminants in Pakistan”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nutrition and Mortality Survey

NUTRITION AND MORTALITY SURVEY Tharparkar, Sanghar and Kamber Shahdadkhot districts of Sindh Province, Pakistan 18-25 March, 2014 1 TABLE OF CONTENT TABLE OF CONTENT ................................................................................................................................... 2 ABBREVIATIONS ........................................................................................................................................... 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................... 4 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................................ 6 2. Objective of the Study ............................................................................................................................... 6 3. Methodology .............................................................................................................................................. 7 3.1 Study area ......................................................................................................................................... 7 3.2 Study population .............................................................................................................................. 7 3.3 Study design ...................................................................................................................................... 8 3.3.1 Sample size -

A Spatio-Temporal Analysis of Rainfall and Drought Monitoring in the Tharparkar Region of Pakistan

remote sensing Article A Spatio-Temporal Analysis of Rainfall and Drought Monitoring in the Tharparkar Region of Pakistan Muhammad Usman 1 and Janet E. Nichol 2,* 1 Centre for Geographical Information System, University of the Punjab, Lahore 54590, Pakistan; [email protected] 2 Department of Geography, School of Global Studies, University of Sussex, Brighton BN19RH, UK * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +852-9363-8044 Received: 6 January 2020; Accepted: 5 February 2020; Published: 10 February 2020 Abstract: The Tharpakar desert region of Pakistan supports a population approaching two million, dependent on rain-fed agriculture as the main livelihood. The almost doubling of population in the last two decades, coupled with low and variable rainfall, makes this one of the world’s most food-insecure regions. This paper examines satellite-based rainfall estimates and biomass data as a means to supplement sparsely distributed rainfall stations and to provide timely estimates of seasonal growth indicators in farmlands. Satellite dekadal and monthly rainfall estimates gave good correlations with ground station data, ranging from R = 0.75 to R = 0.97 over a 19-year period, with tendency for overestimation from the Tropical Rainfall Monitoring Mission (TRMM) and underestimation from Climate Hazards Group Infrared Precipitation with Stations (CHIRPS) datasets. CHIRPS was selected for further modeling, as overestimation from TRMM implies the risk of under-predicting drought. The use of satellite rainfall products from CHIRPS was also essential for derivation of spatial estimates of phenological variables and rainfall criteria for comparison with normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI)-based biomass productivity. This is because, in this arid region where drought is common and rainfall unpredictable, determination of phenological thresholds based on vegetation indices proved unreliable. -

Population According to Religion, Tables-6, Pakistan

-No. 32A 11 I I ! I , 1 --.. ".._" I l <t I If _:ENSUS OF RAKISTAN, 1951 ( 1 - - I O .PUlA'TION ACC<!>R'DING TO RELIGIO ~ (TA~LE; 6)/ \ 1 \ \ ,I tin N~.2 1 • t ~ ~ I, . : - f I ~ (bFICE OF THE ~ENSU) ' COMMISSIO ~ ER; .1 :VERNMENT OF PAKISTAN, l .. October 1951 - ~........-.~ .1',l 1 RY OF THE INTERIOR, PI'ice Rs. 2 ~f 5. it '7 J . CH I. ~ CE.N TABLE 6.-RELIGION SECTION 6·1.-PAKISTAN Thousand personc:. ,Prorinces and States Total Muslim Caste Sch~duled Christian Others (Note 1) Hindu Caste Hindu ~ --- (l b c d e f g _-'--- --- ---- KISTAN 7,56,36 6,49,59 43,49 54,21 5,41 3,66 ;:histan and States 11,54 11,37 12 ] 4 listricts 6,02 5,94 3 1 4 States 5,52 5,43 9 ,: Bengal 4,19,32 3,22,27 41,87 50,52 1,07 3,59 aeral Capital Area, 11,23 10,78 5 13 21 6 Karachi. ·W. F. P. and Tribal 58,65 58,58 1 2 4 Areas. Districts 32,23 32,17 " 4 Agencies (Tribal Areas) 26,42 26,41 aIIjab and BahawaJpur 2,06,37 2,02,01 3 30 4,03 State. Districts 1,88,15 1,83,93 2 19 4,01 Bahawa1pur State 18,22 18,08 11 2 ';ind and Kbairpur State 49,25 44,58 1,41 3,23 2 1 Districts 46,06 41,49 1,34 3,20 2 Khairpur State 3,19 3,09 7 3 I.-Excluding 207 thousand persons claiming Nationalities other than Pakistani. -

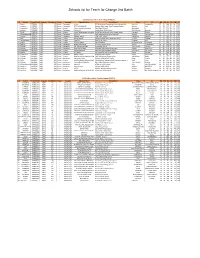

Schools List for Teach for Change 2Nd Batch

Schools list for Teach for Change 2nd Batch ESSP Schools List For Teach for Change (PHASE-II) S # District School Code Program Enrollment Phase Category Operator Name School Name Taluka UC ND NM NS ED EM ES 1 Sukkur ESSP0041 ESSP 435 Phase I Elementary Ali Bux REHMAN Model Computrized School Mubrak Pur. Pano Akil Mubarak Pur 27 40 288 69 19 729 2 Jamshoro ESSP0046 ESSP 363 Phase I Elementary RAZA MUHAMMAD Shaheed Rajib Anmol Free Education System Sehwan Arazi 26 28 132 67 47 667 3 Hyderabad ESSP0053 ESSP 450 Phase I Primary Free Journalist Foundation Zakia Model School Qasimabad 4 25 25 730 68 20 212 4 Khairpur ESSP0089 ESSP 476 Phase I Elementary Zulfiqar Ali Sachal Model Public School Thari Mirwah Kharirah 27 01 926 68 31 711 5 Ghotki ESSP0108 ESSP 491 Phase I Primary Lanjari Development foundation Sachal Sarmast model school dargahi arbani Khangarh Behtoor 27 49 553 69 20 705 6 ShaheedbenazirabaESSP0156 ESSP 201 Phase I Elementary Amir Bux Saath welfare public school (mashaik) Sakrand Gohram Mari 26 15 244 68 08 968 7 Khairpur ESSP0181 ESSP 294 Phase I Elementary Naseem Begum Faiza Public School Sobhodero Meerakh 27 15 283 68 20 911 8 Dadu ESSP0207 ESSP 338 Phase I Primary ghulam sarwar Danish Paradise New Elementary School Kn Shah Chandan 27 03 006 67 34 229 9 TandoAllahyar ESSP0306 ESSP 274 Phase I Primary Himat Ali New Vision School Chumber Jarki 25 24 009 68 49 275 10 Karachi ESSP0336 ESSP 303 Phase I Primary Kishwar Jabeen Mazin Academy Bin Qasim Twon Chowkandi 24 51 388 67 14 679 11 Sanghar ESSP0442 ESSP 589 Phase I Elementary -

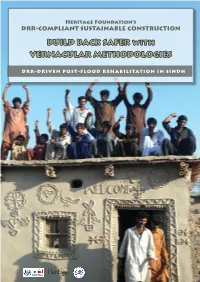

BUILD BACK SAFER with VERNACULAR METHODOLOGIES

Heritage Foundation’s DRR-COMPLIANT SUSTAINABLE CONSTRUCTION BUILD BACK SAFER with VERNACULAR METHODOLOGIES DRR-DRIVEN POST-FLOOD REHABILITATION IN SINDH Introduction to Heritage Foundation eritage Foundation established in 1980 is a Pakistan- based, not-for-profit, social and cultural entrepreneur organization engaged in research, publication and Hconservation of Pakistan’s cultural heritage. The Foundation has been instrumental in saving a large num- ber of heritage treasures and, as UNESCO team leader 2003- 2005, undertook the stabilization of the endangered Shish Ma- hal ceiling of the 16th c. Lahore Fort World Heritage Site. The Foundation publishes monographs and documents relat- ing to heritage and history of Pakistan as well as guides for her- itage safeguarding aspects. It has published a series of invento- ries of historic assets as National Register of Historic Places of Pakistan. In the National Register series, in addition to several Karachi documents listing over 600 historic buildings, docu- ments covering parts of Peshawar, the Siran Valley, Hazara District and Azad Kashmir have been published. Since 2000, its outreach arm KaravanPakistan has involved communities and youth in heritage safeguarding activities. Since 2005, as part of Heritage for Rehabilitation and Devel- opment Program, in partnership with Nokia and Nokia Sie- mens Network, Heritage Foundation has carried out work of rehabilitation of communities, particularly women, affected by the Earthquake 2005 in Northern Pakistan. A 3-year pro- gram, suppported by Scottish Government Fund, Glasgow University and Scottish Pakistan Association on disaster risk resistance (DRR) focusing on women is currently being car- ried out in the Siran Valley. The establishment of KIRAT, Kar- avanPakistan Institute for Research and Training in 2008 has helped in carrying out research and training on varied aspect of sustainable construction techniques drawn from traditional materials and vernacular methods. -

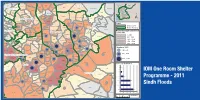

Building Back Stronger

IOM One Room Shelters - 2011 Sindh Floods Response uc, manjhand odero lal village kamil hingoro jhando mari Punjab sekhat khirah Balochistan dasori San gha r ismail jo goth odero lal station khan khahi bilawal hingorjo Matiari roonjho khokhrapar matiari mirabad balouchabad tando soomro chhore bau khan pathan piyaro lund turk ali mari mirpurkhas-05 Sindh shaikh moosa daulatpur shadi pali tajpur pithoro shah mardan shah dhoro naro i m a khan samoon sabho kaplore jheluri Tando Allahpak singhar Yar mosu khatian ii iii iv missan tandojam dhingano bozdar hingorno khararo syed umerkot mirpur old haji sawan khan satriyoon Legend atta muhammad palli tando qaiser araro bhurgari began jarwar mir ghulam hussain Union Council bukera sharif tando hyder dengan sanjar chang mirwah Ume rkot District Boundary hoosri gharibabad samaro road dad khan jarwar girhore sharif seriHyd erabmoolan ad Houses Damaged & Destroyed tando fazal chambar-1 chambar-2 Mirpur Khas samaro kangoro khejrari - Flood 2011 mir imam bux talpur latifabad-20 haji hadi bux 1 - 500 kot ghulam muhammad bhurgari mir wali muhammad latifabad-22 shaikh bhirkio halepota faqir abdullah seri 501 - 1500 ghulam shah laghari padhrio unknown9 bustan manik laghari digri 1501 - 2500 khuda dad kunri 2501 - 3500 uc-iii town t.m. khan pabban tando saindad jawariasor saeedpur uc-i town t.m. khan malhan 3501 - 5000 tando ghulam alidumbalo shajro kantio uc-ii town t.m. khan phalkara kunri memon Number of ORS dilawar hussain mir khuda bux aahori sher khan chandio matli-1 thari soofan shah nabisar road saeed -

Drought Assessment Report Districts Tharparkar and Umerkot

Rapid Assessment Report Draft (19th November 2014) Drought Assessment Report Districts Tharparkar and Umerkot 26th October -- 1st November 2014 Consortium Management Unit PEFSA V Table of Contents 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................................................... 4 2 THE CONTEXT ................................................................................................................ 6 2.1 Background ............................................................................................................................. 6 2.2 Methodology ........................................................................................................................... 6 2.2.1 Objective ....................................................................................................................................... 7 2.2.2 Approach to Assessment .............................................................................................................. 7 2.3 Demographics ......................................................................................................................... 8 2.4 Taluka wise Affected Union Councils of District Tharparkar .................................................. 9 3 MAIN FINDINGS ........................................................................................................... 11 3.1 Affected population and Migration ...................................................................................... 11 3.2 Drought Intensity -

Spatio-Temporal Changes in Economic Development: a Case Study of Sindh Province

Karachi University Journal of Science, 2012, 40, 25-30 25 Spatio-temporal Changes in Economic Development: A case study of Sindh Province Razzaq Ahmed1 and Khalida Mahmood2,* 1Department of Geography, Federal Urdu University of Arts Sciences and Technology, Karachi and 2Department of Geography, University of Karachi, Karachi, Pakistan Abstract: This study has been conducted at a time when Pakistan is passing through an important phase of economic development and reconstruction. Devolution has become an important aspect of the planning and decision making process. Decentralization is being emphasized by both public and private sectors of development. In such a situation, present study focuses on the evaluation of the past and present patterns of the levels of development in various districts of the province of Sindh. This research will certainly contribute to an understanding of the development patterns in the province. Key Words: composite index, level of development, ranking, socio-economic inequality, Z-score. INTRODUCTION METHODOLOGICAL FRAMEWORK Sindh has experienced considerable urbanization since To measure the level of development of the districts of independence in 1947, which has resulted in the explosive Sindh, twelve variables have been employed on thirteen 1 growth of urban centers like Karachi, Hyderabad and districts of 1981 and sixteen districts of 1998 . These Sukkur. The growth of Karachi in particular has been variables are non-agricultural labor force, employment in phenomenal. Its exceptional growth as compared to the rest manufacturing, immigration, own farm, cultivated area, of Sindh, which is basically rural in nature, brings out unique population potential, manufacturing value added (rupees per patterns of socio-economic inequality. -

PAKISTAN – SINDH May – December 2019 Issued in November 2019

IPC ACUTE MALNUTRITION ANALYSIS PAKISTAN – SINDH May – December 2019 Issued in November 2019 Key Figures May – August 2019 SAM (Severe Acute 365,209 Malnutrition) Number of cases 1,000,458 MAM (Moderate Acute Number of 6-59 months children acutely 635,249 Malnutrition) Number of cases malnourished IN NEED OF TREATMENT GAM (Global Acute 1,000,458 Malnutrition) Number of cases How Severe, How Many and When – Acute malnutrition is a major public health problem in all the 8 drought affected districts in the Sindh province. Two districts in the province have Extremely Critical levels (IPC AMN Phase 5) of acute malnutrition – i.e. about every third child in these districts is suffering from acute malnutrition. Six other districts have Critical levels (IPC AMN Phase 4) of acute malnutrition. Although the 6 districts are classified in IPC AMN Phase 4, 2 of them have acute malnutrition levels very close to IPC AMN Phase 5. Where – Among the 8 drought affected districts notified by the Government of Sindh in 2018, the districts with Extremely Critical levels (IPC AMN Phase 5) of acute malnutrition are namely Tharparkar and Umerkot. The other 6 districts – Jamshoro, Kambar Shahdadkot, Badin, Dadu, Sanghar, and Thatta – are classified as being in IPC AMN Phase 4. Of these 6 districts, 2 of them, i.e. Kambar Shahdadkot and Badin, have acute malnutrition levels very close to IPC AMN Phase 5. Why – The major factors contributing to acute malnutrition include very poor quality and quantity of food, high food insecurity, poor sanitation coverage, and high incidence of low birthweight. -

Pakistan Multi-Sectoral Action for Nutrition Program

SFG3075 REV Public Disclosure Authorized Pakistan Multi-Sectoral Action for Nutrition Program Public Disclosure Authorized Environmental and Social Management Framework (ESMF) Directorate of Urban Policy & Strategic Planning, Planning & Public Disclosure Authorized Development Department, Government of Sindh Final Report December 2016 Public Disclosure Authorized Environmental and Social Management Framework Final Report Executive Summary Local Government and Housing Town Planning Department, GOS and Agriculture Department GOS with grant assistance from DFID funded multi donor trust fund for Nutrition in Pakistan are planning to undertake Multi-Sectoral Action for Nutrition (MSAN) Project. ESMF Consultant1 has been commissioned by Directorate of Urban Policy & Strategic Planning to fulfil World Bank Operational Policies and to prepare “Environmental and Social Management Framework (ESMF) for MSAN Project” at its inception stage via assessing the project’s environmental and social viability through various environmental components like air, water, noise, land, ecology along with the parameters of human interest and mitigating adverse impacts along with chalking out of guidelines, SOPs, procedure for detailed EA during project execution. The project has two components under Inter Sectoral Nutrition Strategy of Sindh (INSS), i) the sanitation component of the project aligns with the Government of Sindh’s sanitation intervention known as Saaf Suthro Sindh (SSS) in 13 districts in the province and aims to increase the number of ODF villages through certification while ii) the agriculture for nutrition (A4N) component includes pilot targeting beneficiaries for household production and consumption of healthier foods through increased household food production in 20 Union Councils of 4 districts. Saaf Suthro Sindh (SSS) This component of the project will be sponsored by Local Government and Housing Town Planning Department, Sindh and executed by Local Government Department (LGD) through NGOs working for the Inter-sectoral Nutrition Support Program. -

SELECTED CANDIDATE for DIT 2019-20 IBA IET KHAIRPUR.Pdf

Selected Candidates (Website) IIBAd Slukkur Sukkur IBA University urtv11[] Merit-Qua lity-Exce I len ce Selected Candidates for DIT 2019-20 Program IBA lnstitute of Emerging Technologies, Khairpur Tranining Centers Test Held on: Sunday December 22,zOLg ;.No Seat No Name FatherName lT Center Remarks 1 1010 Ghulam Ali Ghulam Hussain Khairpur Selected 2 1011 Ghulam Mustafa Muhammad Parial Khairpur Selected 3 1013 Humera Muhammad lmtiaz Ali Khairpur Selected 4 1015 lrshad Ali Abdul Kareem Khairpur Selected 5 1016 Jawad Ahmed Ghulam Hyder Khairpur Selected 6 1018 Kaleemullah Safdar Ali Khairpur Selected 7 L02t Mir Murtaza Muhammad Sadiq Khairpur Selected 8 1023 Muhammad lsmail Muhammad Ayoub Khairpur Selected 9 LO27 Muqeem Ahmed Hasil Khan Khairpur Selected 10 1032 Rizwan Ali Muhammad Ali Khairpur Selected 11 1037 Sania Hussain Bux Khairpur Selected t2 1045 Umair Haider lnamullah Khairpur Selected 13 1048 Yasir Ali Akhtiar Ahmed Khairpur Selected 74 1051 Arshad Ali Mukhtiar Ali Khairpur Selected 15 1057 Syed Ali Hassan Syed Nusrat Hassan Khairpur Selected 16 1058 lrfan Ali Asghar Ali Khairpur Selected L7 1051 Ghulam Fatima Muhammad Aslam Khairpur Selected 18 1064 Shahzad Ali Altaf Hussain Khairpur Selected 19 1065 Ghulam Tahir Mureed Hyder Khairpur Selected 20 1503 Ahmed Ali Ghulam Nabi Kingri Selected 2t 1504 Ahsan Ali AliDino Kingri Selected 22 1513 Gulzar Ali Ali Hassan Kingri Selected 23 1514 Haq Nawaz Ali Nawaz Kingri Selected 24 L5L7 Kaleemullah Muhammad Sajjan Kingri Selected 25 1530 Mushahid Hussain Shahid Hussain Kingri Selected 26 -

List of Dehs in Sindh

List of Dehs in Sindh S.No District Taluka Deh's 1 Badin Badin 1 Abri 2 Badin Badin 2 Achh 3 Badin Badin 3 Achhro 4 Badin Badin 4 Akro 5 Badin Badin 5 Aminariro 6 Badin Badin 6 Andhalo 7 Badin Badin 7 Angri 8 Badin Badin 8 Babralo-under sea 9 Badin Badin 9 Badin 10 Badin Badin 10 Baghar 11 Badin Badin 11 Bagreji 12 Badin Badin 12 Bakho Khudi 13 Badin Badin 13 Bandho 14 Badin Badin 14 Bano 15 Badin Badin 15 Behdmi 16 Badin Badin 16 Bhambhki 17 Badin Badin 17 Bhaneri 18 Badin Badin 18 Bidhadi 19 Badin Badin 19 Bijoriro 20 Badin Badin 20 Bokhi 21 Badin Badin 21 Booharki 22 Badin Badin 22 Borandi 23 Badin Badin 23 Buxa 24 Badin Badin 24 Chandhadi 25 Badin Badin 25 Chanesri 26 Badin Badin 26 Charo 27 Badin Badin 27 Cheerandi 28 Badin Badin 28 Chhel 29 Badin Badin 29 Chobandi 30 Badin Badin 30 Chorhadi 31 Badin Badin 31 Chorhalo 32 Badin Badin 32 Daleji 33 Badin Badin 33 Dandhi 34 Badin Badin 34 Daphri 35 Badin Badin 35 Dasti 36 Badin Badin 36 Dhandh 37 Badin Badin 37 Dharan 38 Badin Badin 38 Dheenghar 39 Badin Badin 39 Doonghadi 40 Badin Badin 40 Gabarlo 41 Badin Badin 41 Gad 42 Badin Badin 42 Gagro 43 Badin Badin 43 Ghurbi Page 1 of 142 List of Dehs in Sindh S.No District Taluka Deh's 44 Badin Badin 44 Githo 45 Badin Badin 45 Gujjo 46 Badin Badin 46 Gurho 47 Badin Badin 47 Jakhralo 48 Badin Badin 48 Jakhri 49 Badin Badin 49 janath 50 Badin Badin 50 Janjhli 51 Badin Badin 51 Janki 52 Badin Badin 52 Jhagri 53 Badin Badin 53 Jhalar 54 Badin Badin 54 Jhol khasi 55 Badin Badin 55 Jhurkandi 56 Badin Badin 56 Kadhan 57 Badin Badin 57 Kadi kazia