Sindh Through History and Representations: French

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unclaimed Dividend Details of 2019-20 Interim

LAURUS LABS LIMITED Dividend UNPAID REGISTER FOR THE YEAR INT. DIV. 2019-20 as on September 30, 2020 Sno Dpid Folio/Clid Name Warrant No Total_Shares Net Amount Address-1 Address-2 Address-3 Address-4 Pincode 1 120339 0000075396 RAKESH MEHTA 400003 1021 1531.50 104, HORIZON VIEW, RAHEJA COMPLEX, J P ROAD, OFF. VERSOVA, ANDHERI (W) MUMBAI MAHARASHTRA 400061 2 120289 0000807754 SUMEDHA MILIND SAMANGADKAR 400005 1000 1500.00 4647/240/15 DR GOLWALKAR HOSPITAL PANDHARPUR MAHARASHTRA 413304 3 LLA0000191 MR. RAJENDRA KUMAR SP 400008 2000 3000.00 H.NO.42, SRI VENKATESWARA COLONY, LOTHKUNTA, SECUNDERABAD 500010 500010 4 IN302863 10001219 PADMAJA VATTIKUTI 400009 1012 1518.00 13-1-84/1/505 SWASTIK TOWERS NEAR DON BASCO SCHOOL MOTHI NAGAR HYDERABAD 500018 5 IN302863 10141715 N. SURYANARAYANA 400010 2064 3096.00 C-102 LAND MARK RESIDENCY MADINAGUDA CHANDANAGAR HYDERABAD 500050 6 IN300513 17910263 RAMAMOHAN REDDY BHIMIREDDY 400011 1100 1650.00 PLOT NO 11 1ST VENTURE PRASANTHNAGAR NR JP COLONY MIYAPUR NEAR PRASHANTH NAGAR WATER TANK HYDERABAD ANDHRA PRADESH 500050 7 120223 0000133607 SHAIK RIYAZ BEGUM 400014 1619 2428.50 D NO 614-26 RAYAL CAMPOUND KURNOOL DIST NANDYAL Andhra Pradesh 518502 8 120330 0000025074 RANJIT JAWAHARLAL LUNKAD 400020 35 52.50 B-1,MIDDLE CLASS SOCIETY DAFNALA SHAHIBAUG AHMEDABAD GUJARAT 38004 9 IN300214 11886199 DHEERAJ KOHLI 400021 80 120.00 C 4 E POCKET 8 FLAT NO 36 JANAK PURI DELHI 110058 10 IN300079 10267776 VIJAY KHURANA 400022 500 750.00 B 459 FIRST FLOOR NEW FREINDS COLONY NEW DELHI 110065 11 IN300206 10172692 NARESH KUMAR GUPTA 400023 35 52.50 B-001 MAURYA APARTMENTS 95 I P EXTENSION PATPARGANJ DELHI 110092 12 IN300513 14326302 DANISH BHATNAGAR 400024 100 150.00 67 PRASHANT APPTS PLOT NO 41 I P EXTN PATPARGANJ DELHI 110092 13 IN300888 13517634 KAMNI SAXENA 400025 20 30.00 POCKET I 87C DILSHAD GARDEN DELHI . -

Folkloristic Understandings of Nation-Building in Pakistan

Folkloristic Understandings of Nation-Building in Pakistan Ideas, Issues and Questions of Nation-Building in Pakistan Research Cooperation between the Hanns Seidel Foundation Pakistan and the Quaid-i-Azam University Islamabad Islamabad, 2020 Folkloristic Understandings of Nation-Building in Pakistan Edited by Sarah Holz Ideas, Issues and Questions of Nation-Building in Pakistan Research Cooperation between Hanns Seidel Foundation, Islamabad Office and Quaid-i-Azam University Islamabad, Pakistan Acknowledgements Thank you to Hanns Seidel Foundation, Islamabad Office for the generous and continued support for empirical research in Pakistan, in particular: Kristóf Duwaerts, Omer Ali, Sumaira Ihsan, Aisha Farzana and Ahsen Masood. This volume would not have been possible without the hard work and dedication of a large number of people. Sara Gurchani, who worked as the research assistant of the collaboration in 2018 and 2019, provided invaluable administrative, organisational and editorial support for this endeavour. A big thank you the HSF grant holders of 2018 who were not only doing their own work but who were also actively engaged in the organisation of the international workshop and the lecture series: Ibrahim Ahmed, Fateh Ali, Babar Rahman and in particular Adil Pasha and Mohsinullah. Thank you to all the support staff who were working behind the scenes to ensure a smooth functioning of all events. A special thanks goes to Shafaq Shafique and Muhammad Latif sahib who handled most of the coordination. Thank you, Usman Shah for the copy editing. The research collaboration would not be possible without the work of the QAU faculty members in the year 2018, Dr. Saadia Abid, Dr. -

~~I~II'!- (Randeep Dahiya) ADE (Land & Estate)

GOVERNMENT OF NCT OF DELHI DIRECTORATE OF EDUCATION LAND AND ESTATEBRANCH LUCKNOW ROAD, DELHI-ll0054 No. F./Estate/2017/ l\O:';l\-L\O ~ Dated: \1;-1.-""1'1. CIRCULAR Subject: Direction for ensuring proper facilities in schools of Directorate designated as Polling Stations for Gurudwara Elections-2017 The Heads of such schools which have been designated/notified as polling stations for coming Gurudwara Elections, 2017 are directed to ensure all facilities which are essential for the convenience of general voters such as:- 1. Proper lighting in rooms, passages and veranda 2. Water for drinking and toilet purpose 3. Facilities such as ramp for differently-abled persons 4. Over all cleanliness in school building and premises This may kindly be accorded top priority. ~~I~II'!- (Randeep Dahiya) ADE (Land & Estate) No. F./Estate/2017/ Dated: Copy to the followings: 1. PS to DE 2. All DDEs (District/Zone) 3. ADE (HQ)/Nodal Officer, Gurudwara Elections 4. All HOSs concerned 5. Programmer (MIS) for uploading it ON website (Randeep Dahiya) ADE (Land & Estate) Ward-1 GOVERNMENT OF NCT OF DELHI DIRECTORATE OF GURDWARA ELECTIONS ‘F’ BLOCK, VIKAS BHAWAN, I.P.ESTATE, NEW DELHI – 02. WARD NO. 1 – (ROHINI) Existing Building in P.S. No. Polling Area which it will be located Sarvodya Vidyalaya 1. Rohini Sector 1,2,3 Sector-3,Rohini --do-- Budh Vihar, Vijay Vihar,Anandpur DAM, Shiv Vihar, Karala, Jain Nagar, Kamla Rupali Enclave 2. Rama Vihar, Rajiv Nagar, Sultan Pur Dabas, Dheeraj Vihar,Ser Singh Enclave R.P.Sarvodya(K) 3. Rohini Sector 4,5,6,7,8 Vidyalaya,Rithala --do-- Rohini Sector 21,22,23,24,25, Sardar Colony Sec- 4. -

UNIVERSITA CA'foscari VENEZIA CHAUKHANDI TOMBS a Peculiar

UNIVERSITA CA’FOSCARI VENEZIA Dottorato di Ricerca in Lingue Culture e Societa` indirizzo Studi Orientali, XXII ciclo (A.A. 2006/2007 – A. A. 2009/2010) CHAUKHANDI TOMBS A Peculiar Funerary Memorial Architecture in Sindh and Baluchistan (Pakistan) TESI DI DOTTORATO DI ABDUL JABBAR KHAN numero di matricola 955338 Coordinatore del Dottorato Tutore del Dottorando Ch.mo Prof. Rosella Mamoli Zorzi Ch.mo Prof. Gian Giuseppe Filippi i Chaukhandi Tombs at Karachi National highway (Seventeenth Century). ii AKNOWLEDEGEMENTS During my research many individuals helped me. First of all I would like to offer my gratitude to my academic supervisor Professor Gian Giuseppe Filippi, Professor Ordinario at Department of Eurasian Studies, Universita` Ca`Foscari Venezia, for this Study. I have profited greatly from his constructive guidance, advice, enormous support and encouragements to complete this dissertation. I also would like to thank and offer my gratitude to Mr. Shaikh Khurshid Hasan, former Director General of Archaeology - Government of Pakistan for his valuable suggestions, providing me his original photographs of Chuakhandi tombs and above all his availability despite of his health issues during my visits to Pakistan. I am also grateful to Prof. Ansar Zahid Khan, editor Journal of Pakistan Historical Society and Dr. Muhammad Reza Kazmi , editorial consultant at OUP Karachi for sharing their expertise with me and giving valuable suggestions during this study. The writing of this dissertation would not be possible without the assistance and courage I have received from my family and friends, but above all, prayers of my mother and the loving memory of my father Late Abdul Aziz Khan who always has been a source of inspiration for me, the patience and cooperation from my wife and the beautiful smile of my two year old daughter which has given me a lot courage. -

Makers-Of-Modern-Sindh-Feb-2020

Sindh Madressah’s Roll of Honor MAKERS OF MODERN SINDH Lives of 25 Luminaries Sindh Madressah’s Roll of Honor MAKERS OF MODERN SINDH Lives of 25 Luminaries Dr. Muhammad Ali Shaikh SMIU Press Karachi Alma-Mater of Quaid-e-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah Sindh Madressatul Islam University, Karachi Aiwan-e-Tijarat Road, Karachi-74000 Pakistan. This book under title Sindh Madressah’s Roll of Honour MAKERS OF MODERN SINDH Lives of 25 Luminaries Written by Professor Dr. Muhammad Ali Shaikh 1st Edition, Published under title Luminaries of the Land in November 1999 Present expanded edition, Published in March 2020 By Sindh Madressatul Islam University Price Rs. 1000/- SMIU Press Karachi Copyright with the author Published by SMIU Press, Karachi Aiwan-e-Tijarat Road, Karachi-74000, Pakistan All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any from or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passage in a review Dedicated to loving memory of my parents Preface ‘It is said that Sindh produces two things – men and sands – great men and sandy deserts.’ These words were voiced at the floor of the Bombay’s Legislative Council in March 1936 by Sir Rafiuddin Ahmed, while bidding farewell to his colleagues from Sindh, who had won autonomy for their province and were to go back there. The four names of great men from Sindh that he gave, included three former students of Sindh Madressah. Today, in 21st century, it gives pleasure that Sindh Madressah has kept alive that tradition of producing great men to serve the humanity. -

Honour Killing in Sindh Men's and Women's Divergent Accounts

Honour Killing in Sindh Men's and Women's Divergent Accounts Shahnaz Begum Laghari PhD University of York Women’s Studies March 2016 Abstract The aim of this project is to investigate the phenomenon of honour-related violence, the most extreme form of which is honour killing. The research was conducted in Sindh (one of the four provinces of Pakistan). The main research question is, ‘Are these killings for honour?’ This study was inspired by a need to investigate whether the practice of honour killing in Sindh is still guided by the norm of honour or whether other elements have come to the fore. It is comprised of the experiences of those involved in honour killings through informal, semi- structured, open-ended, in-depth interviews, conducted under the framework of the qualitative method. The aim of my thesis is to apply a feminist perspective in interpreting the data to explore the tradition of honour killing and to let the versions of the affected people be heard. In my research, the women who are accused as karis, having very little redress, are uncertain about their lives; they speak and reveal the motives behind the allegations and killings in the name of honour. The male killers, whom I met inside and outside the jails, justify their act of killing in the name of honour, culture, tradition and religion. Drawing upon interviews with thirteen women and thirteen men, I explore and interpret the data to reveal their childhood, educational, financial and social conditions and the impacts of these on their lives, thoughts and actions. -

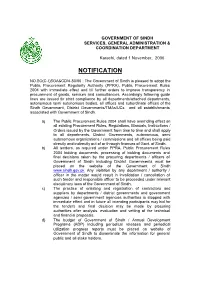

Notification

GOVERNMENT OF SINDH SERVICES, GENERAL ADMINISTRATION & COORDINATION DEPARTMENT Karachi, dated 1 November, 2006 NOTIFICATION NO.SO(C-I)SGA&CD/4-80/06 : The Government of Sindh is pleased to adopt the Public Procurement Regularity Authority (PPRA), Public Procurement Rules 2004 with immediate effect and till further orders to improve transparency in procurement of goods, services and consultancies. Accordingly following guide lines are issued for strict compliance by all departments/attached departments, autonomous semi autonomous bodies, all offices and subordinate offices of the Sindh Government, District Governments/TMAs/UCs and all establishments associated with Government of Sindh. a) The Public Procurement Rules 2004 shall have overriding effect on all existing Procurement Rules, Regulations, Manuals, Instructions / Orders issued by the Government from time to time and shall apply to all departments, District Governments, autonomous, semi autonomous organizations / commissions and all offices being paid directly and indirectly out of or through finances of Govt. of Sindh. b) All tenders, as required under PPRA, Public Procurement Rules 2004 bidding documents, processing of bidding documents and final decisions taken by the procuring departments / officers of Government of Sindh including District Governments must be placed on the website of the Government of Sindh www.sindh.gov.pk Any violation by any department / authority / officer in the matter would result in invalidation / cancellation of such tender and responsible officer to be proceeded under relevant disciplinary laws of the Government of Sindh. c) The practice of enlisting and registration of contractors and suppliers by departments / district governments and government agencies / semi government agencies authorities is stopped with immediate effect and in future all intending participants may bid for the tenders and final decision may be made by procuring authorities after analysis, evaluation and vetting of the technical and financial proposals. -

History of Pacca Fort Hyderabad ISSN (P) 2521-5027

ENGINEERING SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY INTERNATIONAL RESEARCH JOURNAL, VOL.2, NO.4, DEC, 2018 83 ISSN (e) 2520-7393 History of Pacca Fort Hyderabad ISSN (p) 2521-5027 Koshalya Bai Punhani Architect/Assistant Curator 1, Sindhu Chandio Assistant Curator 2 1 Culture Tourism and Archaeology Department Govt: of Sindh 2 Culture Tourism and Archaeology Department Govt: of Sindh Abstract: This article is to discussed about the history of Pacca Fort Hyderabad. Hyderabad is much Famous due to Pacca Qilla, Pacca Fort is the property of mirs. It shows the experts, arts, science of the rich culture of Sindh. The whole article is based on history, era, structure and the main historical buildings in the fort which were built at that time. Every line showing according to the historic perspectives of Sindh. Keywords: History, Pacca Qilla, Culture. 1. HISTORY OF HYDERABAD 1.1 Introduction Hyderabad is known for its historical and cultural background. It is second largest popular city in Sindh and 8th largest city in Pakistan. It is situated at 25”23’ North Latitude and 68”25’ East longitude. The history of this city’s rise and fall is fascinating. In historical accounts some historians have termed this city with sweet name of “Patala”. Some famous writers have termed it as “NairoonKot” while others have made it “ Bairoon”.However, at present it is known as Hyderabad since many years. Corresponding author Email address: [email protected] K.B. PUNHANI et.al: HISTORY OF PACCA FORT HYDERABAD 84 1.2 Patala 1.2.1 Meanings of Patala Experts of Linguistics believe that the name Patala has been derived from word “Patal” which is kind of a flower. -

Sympathy and the Unbelieved in Modern Retellings of Sindhi Sufi Folktales

Sympathy and the Unbelieved in Modern Retellings of Sindhi Sufi Folktales by Aali Mirjat B.A., (Hons., History), Lahore University of Management Sciences, 2016 Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences © Aali Mirjat 2018 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Summer 2018 Copyright in this work rests with the author. Please ensure that any reproduction or re-use is done in accordance with the relevant national copyright legislation. Approval Name: Aali Mirjat Degree: Master of Arts Title: Sympathy and the Unbelieved in Modern Retellings of Sindhi Sufi Folktales Examining Committee: Chair: Evdoxios Doxiadis Assistant Professor Luke Clossey Senior Supervisor Associate Professor Bidisha Ray Co-Supervisor Senior Lecturer Derryl MacLean Supervisor Associate Professor Tara Mayer External Examiner Instructor Department of History University of British Columbia Date Defended/Approved: July 16, 2018 ii Abstract This thesis examines Sindhi Sufi folktales as retold by five “modern” individuals: the nineteenth- century British explorer Richard Burton and four Sindhi intellectuals who lived and wrote in the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries (Lilaram Lalwani, M. M. Gidvani, Shaikh Ayaz, and Nabi Bakhsh Khan Baloch). For each set of retellings, our purpose will be to determine the epistemological and emotional sympathy the re-teller exhibits for the plot, characters, sentiments, and ideas present in the folktales. This approach, it is hoped, will provide us a glimpse inside the minds of the individual re-tellers and allow us to observe some of the ways in which the exigencies of a secular western modernity had an impact, if any, on the choices they made as they retold Sindhi Sufi folktales. -

The Role of Muttahida Qaumi Movement in Sindhi-Muhajir Controversy in Pakistan

ISSN: 2664-8148 (Online) Liberal Arts and Social Sciences International Journal (LASSIJ) https://doi.org/10.47264/idea.lassij/1.1.2 Vol. 1, No. 1, (January-June) 2017, 71-82 https://www.ideapublishers.org/lassij __________________________________________________________________ The Role of Muttahida Qaumi Movement in Sindhi-Muhajir Controversy in Pakistan Syed Mukarram Shah Gilani1*, Asif Salim1-2 and Noor Ullah Khan1-3 1. Department of Political Science, University of Peshawar, Peshawar Pakistan. 2. Department of Political Science, Emory University Atlanta, Georgia USA. 3. Department of Civics-cum-History, FG College Nowshera Cantt., Pakistan. …………………………………………………………………………………………………………… Abstract The partition of Indian sub-continent in 1947 was a historic event surrounded by many controversies and issues. Some of those ended up with the passage of time while others were kept alive and orchestrated. Besides numerous problems for the newly born state of Pakistan, one such controversy was about the Muhajirs (immigrants) who were settled in Karachi. The paper analyses the factors that brought the relation between the native Sindhis and Muhajirs to such an impasse which resulted in the growth of conspiracy theories, division among Sindhis; subsequently to the demand of Muhajir Suba (Province); target killings, extortion; and eventually to military clean-up operation in Karachi. The paper also throws light on the twin simmering problems of native Sindhis and Muhajirs. Besides, the paper attempts to answer the question as to why the immigrants could not merge in the native Sindhis despite living together for so long and why the native Sindhis remained backward and deprived. Finally, the paper aims at bringing to limelight the role of Muttahida Qaumi Movement (MQM). -

Paper Template

International Journal of Arts, Culture, Design & Language Kambohwell Publishers Enterprises Vol. 6, Issue 05, PP. 01-10, May 2019 wwww.kwpublisher.com Block Printing in Sindh, AJRAK and other Contemporaray Products Asra Jan, Bhai Khan Shar Abstract— The purpose of the study is to record the oldest printing firmly believe that the shawl draped on the figure of printing technique hand-block printing and preserve its the priest-king is Ajrak and trefoil motif is actually kakar3 1 evergreen product Ajrak which is the traditional textile of pattern but this theory is debatable as no printing evidence has Sindh. To find out the reasons of abandoning this traditional been discovered yet (Bilgrami 1990, p.19). craft and to witness the difference in block printing done before and now. Different towns of Sindh were visited and eleven artisans (Ajrak-maker/block-printer and block-maker) were interviewed and a questionnaire was filled. The results illustrate that they are suffering from many problems but one of the major problem is lack of clean water which is badly affecting their business. It was also observed that traditional Ajrak formats and patterns are disappearing as only one or two patterns are mostly used nowadays. Whereas the machine block printing has somehow also affected the traditional craft. Despite all the problems they are still so passionate about this craft that they are training their children as well but there are certain evidences that Ajrak-making may not remain a family business anymore as it may be transferred to outsiders in future. However, they have also invented different contemporary products using various types of fabrics and patterns in hand-block printing according to the demand of the Figure 1. -

The People and Land of Sindh by Ahmed Abdullah

THE PEOPLE AD THE LAD OF SIDH Historical perspective By: Ahmed Abdullah Reproduced by Sani Hussain Panhwar Los Angeles, California; 2009 The People and the Land of Sindh; Copyright © www.panhwar.com 1 COTETS Introduction .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 3 The People and the Land of Sindh .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 4 The Jats of Sindh .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 8 The Arab Period .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 10 Mohammad Bin Qasim’s Rule .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 12 Missionary Work .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 15 Sindh’s Progress Under Arabs .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 17 Ghaznavid Period in Sindh .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 21 Naaseruddin Qubacha .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 23 The Sumras and the Sammas .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 25 The Arghans and the Turkhans .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 28 The Kalhoras and Talpurs .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 29 The People and the Land of Sindh; Copyright © www.panhwar.com 2 ITRODUCTIO This material is taken from a book titled “The Historical Background of Pakistan and its People” written by Ahmed Abdulla, published in June 1973, by Tanzeem Publishers Karachi. The original