Classical / Popular / Folk

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BOSTON UNIVERSITY COLLEGE of FINE ARTS Dissertation MERRI FRANQUIN and HIS CONTRIBUTION to the ART of TRUMPET PLAYING by GEOFFRE

BOSTON UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF FINE ARTS Dissertation MERRI FRANQUIN AND HIS CONTRIBUTION TO THE ART OF TRUMPET PLAYING by GEOFFREY SHAMU A.B. cum laude, Harvard College, 1994 M.M., Boston University, 2004 Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts 2009 © Copyright by GEOFFREY SHAMU 2009 Approved by First Reader Thomas Peattie, Ph.D. Assistant Professor of Music Second Reader David Kopp, Ph.D. Associate Professor of Music Third Reader Terry Everson, M.M. Associate Professor of Music To the memory of Pierre Thibaud and Roger Voisin iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Completion of this work would not have been possible without the support of my family and friends—particularly Laura; my parents; Margaret and Caroline; Howard and Ann; Jonathan and Françoise; Aaron, Catherine, and Caroline; Renaud; les Davids; Carine, Leeanna, John, Tyler, and Sara. I would also like to thank my Readers—Professor Peattie for his invaluable direction, patience, and close reading of the manuscript; Professor Kopp, especially for his advice to consider the method book and its organization carefully; and Professor Everson for his teaching, support and advocacy over the years, and encouraging me to write this dissertation. Finally, I would like to acknowledge the generosity of the Voisin family, who granted interviews, access to the documents of René Voisin, and the use of Roger Voisin’s antique Franquin-system C/D trumpet; Veronique Lavedan and Enoch & Compagnie; and Mme. Courtois, who opened her archive of Franquin family documents to me. v MERRI FRANQUIN AND HIS CONTRIBUTION TO THE ART OF TRUMPET PLAYING (Order No. -

Playing Music for Morris Dancing

Playing Music for Morris Dancing Jeff Bigler Last updated: June 28, 2009 This document was featured in the December 2008 issue of the American Morris Newsletter. Copyright c 2008–2009 Jeff Bigler. Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.3 or any later version published by the Free Software Foundation; with no Invariant Sections, no Front-Cover Texts, and no Back-Cover Texts. This document may be downloaded via the internet from the address: http://www.jeffbigler.org/morris-music.pdf Contents Morris Music: A Brief History 1 Stepping into the Role of Morris Musician 2 Instruments 2 Percussion....................................... 3 What the Dancers Need 4 How the Dancers Respond 4 Tempo 5 StayingWiththeDancers .............................. 6 CuesthatAffectTempo ............................... 7 WhentheDancersareRushing . .. .. 7 WhentheDancersareDragging. 8 Transitions 9 Sticking 10 Style 10 Border......................................... 10 Cotswold ....................................... 11 Capers......................................... 11 Accents ........................................ 12 Modifying Tunes 12 Simplifications 13 Practices 14 Performances 15 Etiquette 16 Conclusions 17 Acknowledgements 17 Playing Music for Morris Dancing Jeff Bigler Morris Music: A Brief History Morris dancing is a form of English street performance folk dance. Morris dancing is always (or almost always) performed with live music. This means that musicians are an essential part of any morris team. If you are reading this document, it is probably because you are a musician (or potential musician) for a morris dance team. Good morris musicians are not always easy to find. In the words of Jinky Wells (1868– 1953), the great Bampton dancer and fiddler: . [My grandfather, George Wells] never had no trouble to get the dancers but the trouble was sixty, seventy years ago to get the piper or the fiddler—the musician. -

A Selection of Contemporary Fanfares for Multiple Trumpets Demonstrating Evolutionary Processes in the Fanfare Form

MODERN FORMS OF AN ANCIENT ART: A SELECTION OF CONTEMPORARY FANFARES FOR MULTIPLE TRUMPETS DEMONSTRATING EVOLUTIONARY PROCESSES IN THE FANFARE FORM Paul J. Florek, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2015 APPROVED: Keith Johnson, Major Professor Eugene Corporon, Committee Member John Holt, Committee Member and Chair of the Department of Instrumental Studies Benjamin Brand, Director of Graduate Studies in Music James C. Scott, Dean of the College of Music Costas Tsatsoulis, Interim Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Florek, Paul J. Modern Forms of an Ancient Art: A Selection of Contemporary Fanfares for Multiple Trumpets Demonstrating Evolutionary Processes in the Fanfare Form. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2015, 73 pp., 1 table, 26 figures, references, 96 titles. The pieces discussed throughout this dissertation provide evidence of the evolution of the fanfare and the ability of the fanfare, as a form, to accept modern compositional techniques. While Britten’s Fanfare for St. Edmundsbury maintains the harmonic series, it does so by choice rather than by the necessity in earlier music played by the baroque trumpet. Stravinsky’s Fanfare from Agon applies set theory, modal harmonies, and open chords to blend modern techniques with medieval sounds. Satie’s Sonnerie makes use of counterpoint and a rather unusual, new characteristic for fanfares, soft dynamics. Ginastera’s Fanfare for Four Trumpets in C utilizes atonality and jazz harmonies while Stravinsky’s Fanfare for a New Theatre strictly coheres to twelve-tone serialism. McTee’s Fanfare for Trumpets applies half-step dissonance and ostinato patterns while Tower’s Fanfare for the Uncommon Woman demonstrates a multi-section work with chromaticism and tritones. -

Winter 2017 AR

Published by the American Recorder Society, Vol. LVIII, No. 4 • www.americanrecorder.org winter 2017 Editor’s ______Note ______ ______ ______ ______ Volume LVIII, Number 4 Winter 2017 Features love a good mystery, and read with interest David Lasocki’s article excerpted Juan I and his Flahutes: What really happened fromI his upcoming book—this piece seek- in Medieval Aragón? . 16 recorder in Medieval ing answers about the Aragón By David Lasocki (page 16). While the question of what happened may never be definitively Departments answered, this historical analysis gives us possibilities (and it’s fortunate that research Advertiser Index . 32 was completed before the risks increased even more for travel in modern Catalonia). Compact Disc Reviews . 9 Compact Disc Reviews give us a Two sets of quintets: Seldom Sene and means to hear Spanish music from slightly later, played by Seldom Sene, plus we Flanders Recorder Quartet with Saskia Coolen can enjoy a penultimate CD in the long Education . 13 Flanders Recorder Quar tet collaboration Aldo Abreu is impressed with the proficiency of (page 9). In Music Reviews, there is music to play that is connected to Aragón and to young recorder players in Taiwan others mentioned in this issue (page 26). Numerous studies tout the benefits to Music Reviews. 26 a mature person who plays music, but now Baroque works, plus others by Fulvio Caldini there is a study that outlines measurable benefits for the listener, as well (page 6). As I President’s Message . 3 write these words, it’s Hospice and Palliative ARS President David Podeschi on the Care Month. -

BRIDWELL-BRINER, KATHRYN EILEEN, DMA the Horn In

BRIDWELL-BRINER, KATHRYN EILEEN, D.M.A. The Horn in America from Colonial Society to 1842: Performers, Instruments, and Repertoire. (2014) Directed by Dr. Randy Kohlenberg. 294 pp. The purpose of this study was to address an aspect of the history of the horn neglected in traditional horn scholarship—that of the horn in America from the development of colonial society (ca. 1700) to the early days of the antebellum era (ca. 1840). This choice of time period avoided the massive influx of foreign musicians and exponential growth of American musical activities after 1840, as well as that of the general population, as this information would become too unwieldy for anything but studies of individual cities, regions, or specific musical groups. This time frame also paralleled the popularity of the horn virtuoso in Europe given so much attention by horn scholars. Additionally, all information gathered through examination of sources has been compiled in tables and included in the appendices with the intention of providing a point of reference for others interested in the horn in early America. This survey includes a brief introduction, review of literature, the ways in which the horn was utilized in early America, the individuals and businesses that made or sold horns and horn-related accoutrements such as music, tutors, crooks, and mouthpieces as well as an examination of the body of repertoire gleaned from performances of hornists in early America. THE HORN IN AMERICA FROM COLONIAL SOCIETY TO 1842: PERFORMERS, INSTRUMENTS, AND REPERTOIRE by Kathryn -

Corrina Hewat Reviews

Corrina Hewat | reviews | My Favourite Place Footstompin Music FSR1719 (2003) After 10 years as a full-time musician, and having already appeared on albums by some 20 different artists and groups, Scottish harpist and singer Corrina Hewat hasn't exactly rushed into releasing her debut solo CD but she's not been idle, either, emerging as a performer, composer, arranger and tutor of equal note, with a touring schedule that's taken her across three continents. She's also been a key figure in several landmark Scottish ventures of recent years, including the 2002 Scottish Women tour, Linn Record’s Complete Works of Robert Burns series, and the 31-strong Unusual Suspects concert at this year's Celtic Connections festival. The central trait unifying Hewat's multiple gifts is her fondness and facility for exploring interfaces -- chiefly between folk and jazz, but also in among blues, soul and classical influences. All this breadth of experience and style finds marvellously concentrated yet spacious expression on My Favourite Place complemented by David Milligan on piano, percussionist Donald Hay, and Karine Polwart's backing harmonies. On the vocal front, tracks range from a bold, spiky updating of Sheath And Knife to an understated take on the jazz standard When I Dream. Hewat's own compositions -- such as the brilliantly wayward Traffic and the soulful, title track -- feature prominently among the tunes, together with a handful of beautifully wrought traditional numbers. Sue Wilson The Sunday Herald As soon as I started to listen to Corrina’s beautiful debut solo CD – a delicious, mellow, richly satisfying fusion of jazz/roots/blues styles (pure magic to a person of my musical tastes!), I was immediately transported to my very own ‘favourite place’. -

Dance and Teachers of Dance in Eighteenth-Century Bath

DANCE AND TEACHERS OF DANCE IN EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY BATH Trevor Fawcett Compared with the instructor in music, drawing, languages, or any other fashionable accomplishment, the dancing master (and, in time, his female counterpart) enjoyed an oddly ambiguous status in 18th-century society. Seldom of genteel birth himself, and by education and fortune scarcely fit to rank even with the physician or the clergyman, he found himself the acknowledged expert and authority in those very social graces that were sup posedly the mark and birthright of the polite world alone. Ostensibly he taught dance technique: the execution of the minuet and formal dances, the English country dances in all their variants, the modish cotillion, and the late-century favourites - the Scottish and Irish steps. But while for his pupils a mastery of these skills was indeed a necessary prelude to the ballroom, the fundamental importance of a dancing master lay in the coaching he provided in etiquette, in deportment, and in the cultivation of that air of relaxed assurance so much admired by contemporaries. There was general agreement with John Locke's view that what counted most in dancing was not learning the figures and 'the jigging part' but acquiring an apparent total naturalness, freedom and ease in bodily movement. Clumsiness equated with boorish ness, vulgarity, rusticity, bad manners, bad taste. On several occasions the influential, taste-forming Spectator saw fit to remind its readers about the value of dancing, 'at least, as belongs to the Behaviour and an handsom Carriage of the Body'. Graceful manners and agreeable address ranked among the most reliable indicators of good breeding, and it was 'the proper Business of a Dancing-Master to regulate these Matters' .1 In theory, it might have been argued, only the more humbly born social aspirants 28 TREVOR FAWCETT ought to have needed the services of 'those great polishers of our manners', the dancing masters. -

The Pipe and Tabor

The magazine of THE COUN1RY DANCE SOCIETY OF AMERICA Calendar of Events EDI'roR THE May Gadd April 4 - 6, 1963 28th ANNUAL MOUNTAIN FOLPt: FESTIVAL, Berea, Ky. ASSOCIATE EDI'roR :tV'.ia.y 4 C.D.s. SffiiNJ FESTIVAL, Hunter College, counTRY A.C. King New York City. DAnCER CONTRIBUTING EDI'roRS l'ia.Y 17 - 19 C.D.S. SPROO DANCE WEEKEND, Hudson Lee Haring }~rcia Kerwit Guild Farm, Andover, N.J. Diana Lockard J .Donnell Tilghman June 28 - July 1 BOSTON C.D.S.CENI'RE DAM::E WEEKEND Evelyn K. \'/ells Roberta Yerkes at PINEWOODS, Buzzards Bay, Masa. ART .EDI'roR NATIONAL C.D.S. P:niDIOOJlS CAMP Genevieve Shimer August 4 - 11 CHAMBER MUSIC WEEK) Buzzards August 11 - 25 'lWO DANCE WEEKS ) Bay, THE COUNTRY DANC:lli is published twice a year. Subscription August 25 - Sept.l FOLK MUSIC WEEK ) Hass. is by membership in the Country Dance Society of America (annual dues $5,educational institutions and libraries $3) marriages Inquiries and subscriptions should be sent to the Secretary Country Dance Society of America, 55 Christopher St. ,N.Y .1.4 COMBS-ROGERS: On December 22, 1962, in Pine Mountain,Ky., Tel: ALgonquin 5-8895 Bonnie Combs to Chris Rogers • DAVIS-HODGKIN: On January 12, 196.3, in Germantown, Pa., Copyright 1963 by the Count17 Dance Society Inc. Elizabeth Davis to John P. Hodgkin. CORNWELL-HARING: On January 19, 196.3, in New York City, Table of Contents Margery R. Cornwell to Lee Haring. Page Births CalPndar of Events • • • • • • • • 3 AVISON: To Lois and Richard Avison of Chapleau,Ont., Marriages and Births • • • • • • • .3 on August 7, 1962, a daughter, SHANNON. -

Lps Page 1 -.:: GEOCITIES.Ws

LPs ARTIST TITLE LABEL COVER RECORD PRICE 10 CC SHEET MUSIC UK M M 5 2 LUTES MUSIC IN THE WORLD OF ISLAM TANGENT M M 10 25 YEARS OF ROYAL AT LONDON PALLADIUM GF C RICHARD +E PYE 2LPS 1973 M EX 20 VARIETY JOHN+SHADOWS 4 INSTANTS DISCOTHEQUE SOCITY EX- EX 20 4TH IRISH FOLK FESTIVAL ON THE ROAD 2LP GERMANY GF INTRERCORD EX M 10 5 FOLKFESTIVAL AUF DER LENZBURG SWISS CLEVES M M 15 5 PENNY PIECE BOTH SIDES OF 5 PENNY EMI M M 7 5 ROYALES LAUNDROMAT BLUES USA REISSUE APOLLO M M 7 5 TH DIMENSION REFLECTION NEW ZEALAND SBLL 6065 EX EX 6 5TH DIMENSION EARTHBOUND ABC M M 10 5TH DIMENSION AGE OF AQUARIUS LIBERTY M M 12 5TH DIMENSION PORTRAIT BELL EX EX- 5 75 YEARS OF EMI -A VOICE WITH PINK FLOYD 2LPS BOX SET EMI EMS SP 75 M M 40 TO remember A AUSTR MUSICS FROM HOLY GROUND LIM ED NO 25 HG 113 M M 35 A BAND CALLED O OASIS EPIC M M 6 A C D C BACK IN BLACK INNER K 50735 M NM 10 A C D C HIGHWAY TO HELL K 50628 M NM 10 A D 33 SAME RELIGIOUS FOLK GOOD FEMALE ERASE NM NM 25 VOCALS A DEMODISC FOR STEREO A GREAT TRACK BY MIKE VICKERS ORGAN EXP70 M M 25 SOUND DANCER A FEAST OF IRISH FOLK SAME IRISH PRESS POLYDOR EX M 5 A J WEBBER SAME ANCHOR M M 7 A PEACOCK P BLEY DUEL UNITY FREEDOM EX M 20 A PINCH OF SALT WITH SHIRLEY COLLINS 1960 HMV NM NM 35 A PINCH OF SALT SAME S COLLINS HMV EX EX 30 A PROSPECT OF SCOTLAND SAME TOPIC M M 5 A SONG WRITING TEAM NOT FOR SALE LP FOR YOUR EYES ONLY PRIVATE M M 15 A T WELLS SINGING SO ALONE PRIVATE YPRX 2246 M M 20 A TASTE OF TYKE UGH MAGNUM EX EX 12 A TASTE OF TYKE SAME MAGNUM VG+ VG+ 8 ABBA GREATEST HITS FRANCE VG 405 EX EX -

Praise the Legacy of Music Associated with Admiral Nelson by Gavin Atkin ‘Saturday Night at Sea’ by George Cruikshank

EDS Autumn 2005 qx6 18/8/05 11:27 am Page 8 Nelson’s Praise The legacy of music associated with Admiral Nelson by Gavin Atkin ‘Saturday Night at Sea’ by George Cruikshank s the recent international Spithead other players and noted them down in popularity as a result. The same kind of review showed, Admiral Lord their personal tune-books. This was also process seems to have taken place at ANelson in 2005 still casts a the period when the modern 4/4 the level of popular music, for no fewer shadow as long as his London column hornpipe became popular and several of than seven tunes that have come down is tall. And the party isn’t over yet, for the tunes named after Nelson are of this to us today bear the great admiral’s the bicentenary of his death at the Battle type. name, and at least three bear several of Trafalgar doesn’t actually take place Some of the tunes came into wide other names as well! until the 21st of October. If you haven’t use and have come down to us through Perhaps the most striking example, organised your event yet, there’s still the tradition, while others are still being and probably the one best known to time, just about... rediscovered – many of today’s bands English-style musicians, is the tune Anniversaries on this scale make us well known for playing for country known by the name of ‘The Bridge of wonder what people – sailors and dancing, such as The Old Swan Band, Lodi’ and also as ‘Lord Nelson’s landsmen and women – played and The Bismarcks, The Committee Band Hornpipe’. -

Gloucestershire Folk Song

Glos.Broadsht.7_Layout 1 15/10/2010 14:35 Page 1 1 4 A R iver Avon A4104 A3 8 9 Randwick cheese rolling and Randwick Wap Dover’s Games and Scuttlebrook Wake, Chipping 2 A about!’ and they routed the 8 Chipping 4 A JANUARY 4 A 43 First Sunday and second Saturday in May Campden – Friday and Saturday after Spring Bank 1 4 Camden French in hand-to-hand 4 Blow well and bud well and bear well Randwick is one Holiday 5 0 fighting. For this feat the 1 8 God send you fare well A3 Gloucestershires were of the two places The ‘Cotswold Olimpicks’ or ‘Cotswold Games’ were A43 A 8 3 Every sprig and every spray in Gloucestershire instituted around 1612 by Robert Dover. They mixed 8 allowed to wear two hat or A bushel of apples to be that still practices traditional games such as backsword fighting and cap badges – the only 2 9 given away cheese-rolling. On shin-kicking with field sports and contests in music 4 10 MORETON- regiment to do so. The Back Dymock A 1 IN-MARSH On New Year’s day in the TEWKESBURY 4 Badge carries an image of the first Sunday in A n 3 Wo olstone 4 morning r 5 A the Sphinx and the word May cheeses are e 1 2 4 ev 4 4 M50 8 S ‘Egypt’. The Regiment is now From dawn on New Year’s Day, rolled three times r 3 Gotherington e A 5 A v i part of The Rifles. -

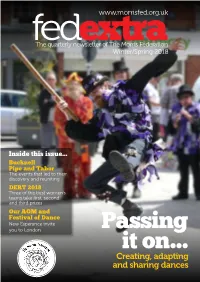

Creating, Adapting and Sharing Dances

www.morrisfed.org.uk fedThe quarterly newsletterextra of The Morris Federation Winter/Spring 2018 Inside this issue... Bucknell Pipe and Tabor The events that led to their discovery and reuniting DERT 2018 Three of the best women's teams take first, second and third prizes Our AGM and Festival of Dance New Esperance invite you to London Passing it on... Creating, adapting and sharing dances www.morrisfed.org.uk www.morrisfed.org.uk fed www.morrisfed.org.uk fed extraWinter/Spring 2018 extraWinter/Spring 2018 fedextra inside Winter/Spring 2018 this Festival of issue MorrisWinter/Spring 2018 20th-22nd September 2018 Our AGM and Festival of Dance – London New Esperance Morris are proud New Esperance Morris invite you20 to the Bucknell Pipe to host 2018’s Morris Federation and Tabor AGM in our hometown, the Morris Federation AGM and a wonderful 08 vibrant city of London. We would weekend of dance hosted in the heart like to invite all Federation sides to celebrate a Festival of Morris weekend of our vibrant capital city with us - a celebration of the living Our programme is overleaf, and Saturday evening’s entertainment tradition of Morris which we are proud more details about the schedule, includes a ceilidh, performances, to champion. local area, workshops, ceilidhs, Library lecture, a folk costume DERT and performances are available on exhibition, sessions and songs. New EsperanceBecoming Morris draw their oura websiteclog - where you willWomen's also On the Sunday there will Boughton Sharing women ethos from Mary Neal, a pioneer of find a booking form and payment be dance and music workshops led Morris dances morris in her time,maker who originally – part information.