Records Ofeayl~Q English Dan'iay

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OXFORDSHIRE. [ KELLY's

390 PllB OXFORDSHIRE. [ KELLY's PUBLIC HOUSES-continued. GrapecS, Mrs. Charlotte Childs, 4 George street, Oxford Crown, .Arthur John Stanton, Charlton, Oxford Green Dragon, Henry Stone, 10 St. Aldate's st. Oxford Crown, William Waite, Souldern, Banbury Green Man, Charles Archer, Mollington, Banbury Crown inn, James N. Waters, Nuffield, Henley-on-Thms Green ::\Ian, Charles Bishop, Hi~moor,Henley-on-Thams Crown, Thomas "\'Vebb, Play hatch, Dunsden, Reading Greyhound, Miss Ellen Garlick, Ewelme, \Yallingf.ord Crown, Richard Wheeler, Stadhampton, "\Yallingford Greyhound, George King, Woodcote, Reading Crown inn, Mrs. R. Whichelo, Dorchester, \Yallingford Greyhound, Mrs. l\1. A. Vokins,Market pl.Henley-on-Thms Crown inn, James Alfred Whiting, 59a, Cornmkt. st.Oxfrd Greyhound, Harry \Villis, 10 Worcester street k Glou- Crown & Thistle, Mrs. H. Gardener, 10 Market st. Oxford cester green, Oxford Crown & Thistle, William Lee, Headington quarry,Oxford Griffin, Mrs. l\lartha Basson, K ewland, "\Yitney Crown & Tuns, Geo. J ones, New st. Deddington, Oxford Griffin, Charles Best, Church rd. Caversham, Reading Dashwood Arms, Benjamin Long, Kirtlington, Oxford Griffin inn, Charles Stephen Smith, Swerford, Enstone Dog inn, D. Woolford, Rotherfield Peppard,Henly.-on-T Half :Moon, James Bennett, 17 St. Clement's st. Oxford Dog & Anchor, Richard Young, Kidlington, Oxford Half ~Ioon, Thomas Bristow N eal, Cuxham, Tetsworth Dog & Duck, Thomas Page, Highmoor, Henley-on-Thms Hand &; Shears, Thomas Wilsdon,H'andborough,Woodstck Dog & Gun, John Henry Thomas, 6 North Bar st.Banbury Harcourt Arms, Charles Akers, Stanton Harcourt,Oxford Dog & Partridge, Thos. Warren, West Adderbury, Banbry Harcourt Arms, George ~Iansell, North Leigh, Witney Dolphin & Anchor, J. Taylor, 43 St. -

Applications Determined Under Delegated Powers PDF 317 KB

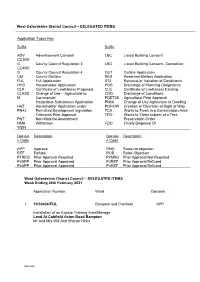

West Oxfordshire District Council – DELEGATED ITEMS Application Types Key Suffix Suffix ADV Advertisement Consent LBC Listed Building Consent CC3RE G County Council Regulation 3 LBD Listed Building Consent - Demolition CC4RE G County Council Regulation 4 OUT Outline Application CM County Matters RES Reserved Matters Application FUL Full Application S73 Removal or Variation of Condition/s HHD Householder Application POB Discharge of Planning Obligation/s CLP Certificate of Lawfulness Proposed CLE Certificate of Lawfulness Existing CLASS Change of Use – Agriculture to CND Discharge of Conditions M Commercial PDET28 Agricultural Prior Approval Hazardous Substances Application PN56 Change of Use Agriculture to Dwelling HAZ Householder Application under POROW Creation or Diversion of Right of Way PN42 Permitted Development legislation. TCA Works to Trees in a Conservation Area Telecoms Prior Approval TPO Works to Trees subject of a Tree PNT Non Material Amendment Preservation Order NMA Withdrawn FDO Finally Disposed Of WDN Decisio Description Decisio Description n Code n Code APP Approve RNO Raise no objection REF Refuse ROB Raise Objection P1REQ Prior Approval Required P2NRQ Prior Approval Not Required P3APP Prior Approval Approved P3REF Prior Approval Refused P4APP Prior Approval Approved P4REF Prior Approval Refused West Oxfordshire District Council – DELEGATED ITEMS Week Ending 26th February 2021 Application Number. Ward. Decision. 1. 19/03436/FUL Bampton and Clanfield APP Installation of an Equine Training Area/Manege Land At Cobfield Aston Road Bampton Mr And Mrs Will And Sharon Hicks DELGAT 2. 20/01655/FUL Ducklington REF Erection of four new dwellings and associated works (AMENDED PLANS) Land West Of Glebe Cottage Lew Road Curbridge Mr W Povey, Mr And Mrs C And J Mitchel And Abbeymill Homes L 3. -

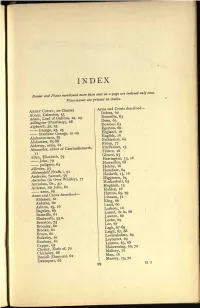

Names and Places Mentioned More Than Once on a Page Are Indexed Only Once

INDEX Names and Places mentioned more than once on a page are indexed only once. Place-names are printed in italics. Arms and Crests described- ABBEY COURT, see Chester Delves, 62 Abney, Grimston, 55 Adam, Lord of Garston, 24, 29 Domville, 63 Adlington (Prestbury), 68 Done, 63 Downes, 63 Aigburth, 22, 23 Egerton, 60 Grange, 23, 25 England, 16 Stanlawe Grange, 21-29 English, 16 Alabaster-men, 87 Fetherston, 64 Alabasters, 85-88 Fitton, 77 Aldersey, arms, 61 Alexander, abbot of Cambuskenneth, FitzWalter, 15 France, 16 II Cleave, 65 Alien, Elizabeth, 79 Harrington, 13, 16 John, 79 Hawarden, 68 pedigree, 64 Helsby, 16 Allerton, 23 Henshaw, 64 Alstonefield (Staffs.), 91 Hesketh, 15, 16 Andrews, Samuel, 56 Higginson, 64 Antrobus (in Over Whitley), 77 Hockenhull, 65 Antrobus, Dr., 40 Hoghton, 15 Arderne, Sir John, 60 Holden, 16 arms, 60 Arms and Crests described Hutton, 65, 79 Johnson, 71 Aldersey, 6I King, 66 Arderne, 60 Land, 66 Ashton, 15, 16 Lathom, 16 Baguley, 69 Laund, de la, 66 Bamville, 61 Lawton, 66 Bludworth, 53 «. Leche, 69 Brereton, 75 Lee, 67 Bromley, 60 Legh, 67-69 Brooke, 61 Leigh, 67, 68 Bruen, 60 Levenshulme, 69 Bulkeley, 61 Leycester, 69 Bunbury, 61 Lymme, 63, 68 Capper, 62 Mainwaring, 69, 70 Chester, Earls of, 70 Mallory, 70 Chicheley, 68 Man, 16 Daniell (Danyers), 62 Massey, 15, 7° Davenport, 62 99 H2 100 Index Arms and Crests described Barnton (in Great Budworth), 73, 80 Maude, 16 Barrow, Thomas, 90 Merbrooke, 16 Bartlett, J. Adams, 38 Middleton, 13 Beamont, William, 83, 84 Millington, 71 Beattie, Frederick, 21 Minshull, 71 Beauclerk, Mary, 19 Molyneux, 16 Sydney, 19 Morley, 77 family, 8, 9 Newton, 73 Beaumaris, 61 Norris, 13, 16 Ben, Mary, 53 Norris of Ock wells, 16 Bennet, Anne, 82 Oldfield, 72 John, 82 Oulton, 72 Bentham (Yorks.), 64 Pennington, 72 Bickerton, 92 Finder, 72 Billinge, Lawrence, 92 Pownall, 73, So Bindloss, Francis, 19 n. -

Playing Music for Morris Dancing

Playing Music for Morris Dancing Jeff Bigler Last updated: June 28, 2009 This document was featured in the December 2008 issue of the American Morris Newsletter. Copyright c 2008–2009 Jeff Bigler. Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.3 or any later version published by the Free Software Foundation; with no Invariant Sections, no Front-Cover Texts, and no Back-Cover Texts. This document may be downloaded via the internet from the address: http://www.jeffbigler.org/morris-music.pdf Contents Morris Music: A Brief History 1 Stepping into the Role of Morris Musician 2 Instruments 2 Percussion....................................... 3 What the Dancers Need 4 How the Dancers Respond 4 Tempo 5 StayingWiththeDancers .............................. 6 CuesthatAffectTempo ............................... 7 WhentheDancersareRushing . .. .. 7 WhentheDancersareDragging. 8 Transitions 9 Sticking 10 Style 10 Border......................................... 10 Cotswold ....................................... 11 Capers......................................... 11 Accents ........................................ 12 Modifying Tunes 12 Simplifications 13 Practices 14 Performances 15 Etiquette 16 Conclusions 17 Acknowledgements 17 Playing Music for Morris Dancing Jeff Bigler Morris Music: A Brief History Morris dancing is a form of English street performance folk dance. Morris dancing is always (or almost always) performed with live music. This means that musicians are an essential part of any morris team. If you are reading this document, it is probably because you are a musician (or potential musician) for a morris dance team. Good morris musicians are not always easy to find. In the words of Jinky Wells (1868– 1953), the great Bampton dancer and fiddler: . [My grandfather, George Wells] never had no trouble to get the dancers but the trouble was sixty, seventy years ago to get the piper or the fiddler—the musician. -

The Reformation of the Generations: Age, Ancestry and Memory in England 1500-1700

The Reformation of the Generations: Age, Ancestry and Memory in England 1500-1700 Folger Shakespeare Library Spring Semester Seminar 2016 Alexandra Walsham (University of Cambridge): [email protected] The origins, impact and repercussions of the English Reformation have been the subject of lively debate. Although it is now widely recognised as a protracted process that extended over many decades and generations, surprisingly little attention has been paid to the links between the life cycle and religious change. Did age and ancestry matter during the English Reformation? To what extent did bonds of blood and kinship catalyse and complicate its path? And how did remembrance of these events evolve with the passage of the time and the succession of the generations? This seminar will investigate the connections between the histories of the family, the perception of the past, and England’s plural and fractious Reformations. It invites participants from a range of disciplinary backgrounds to explore how the religious revolutions and movements of the period shaped, and were shaped by, the horizontal relationships that early modern people formed with their sibilings, relatives and peers, as well as the vertical ones that tied them to their dead ancestors and future heirs. It will also consider the role of the Reformation in reconfiguring conceptions of memory, history and time itself. Schedule: The seminar will convene on Fridays 1-4.30pm, for 10 weeks from 5 February to 29 April 2016, excluding 18 March, 1 April and 15 April. In keeping with Folger tradition, there will be a tea break from 3.00 to 3.30pm. -

Total Carbon Footprint Per Capita

District Data Analysis Service August 2021 Chart of the month August 2021 – Total carbon footprint per capita This month’s chart looks at the carbon footprint per person based on seven underlying sources of emissions data: Electricity, Gas, Other Heating, Car Driving, Van Driving, Flights, and Consumption of goods and services. This is particularly interesting given the current worldwide environmental crisis. This data has been obtained from the place-based carbon calculator produced with funding from UK Research and Innovation through the Centre for Research into Energy Demand Solutions. The areas in the maps are displayed at Lower-layer Super Output Area (LSOA) level. This dataset has been made available in July 2021. For more information, please visit the Place-Based Carbon calculator. Key findings: Overall, all the districts in Oxfordshire scored above the England overall carbon footprint of 8,355 Kg CO2 per capita, where highest means worst and lowest means best. Areas with the highest scores in the districts were Flights, Cars, Food & Drink, and Recreation. The following chart shows the amount of Kg CO2 for every source in England compared to the districts in Oxfordshire. The dashed line (---) across the chart shows the England target for 2032 (2,849). Figure 1. Sources of Kg CO2 per capita in England and the districts, 2021 Source: Place-Based Carbon Calculator, 2021 District Data Analysis Service August 2021 Figure 2. Map of Kg CO2 per capita in Oxfordshire’s LSOAs Source: Place-Based Carbon Calculator, 2021. District Data Analysis Service August 2021 Cherwell Cherwell scored second best with 11,048 Kg CO2 per capita. -

Winter 2017 AR

Published by the American Recorder Society, Vol. LVIII, No. 4 • www.americanrecorder.org winter 2017 Editor’s ______Note ______ ______ ______ ______ Volume LVIII, Number 4 Winter 2017 Features love a good mystery, and read with interest David Lasocki’s article excerpted Juan I and his Flahutes: What really happened fromI his upcoming book—this piece seek- in Medieval Aragón? . 16 recorder in Medieval ing answers about the Aragón By David Lasocki (page 16). While the question of what happened may never be definitively Departments answered, this historical analysis gives us possibilities (and it’s fortunate that research Advertiser Index . 32 was completed before the risks increased even more for travel in modern Catalonia). Compact Disc Reviews . 9 Compact Disc Reviews give us a Two sets of quintets: Seldom Sene and means to hear Spanish music from slightly later, played by Seldom Sene, plus we Flanders Recorder Quartet with Saskia Coolen can enjoy a penultimate CD in the long Education . 13 Flanders Recorder Quar tet collaboration Aldo Abreu is impressed with the proficiency of (page 9). In Music Reviews, there is music to play that is connected to Aragón and to young recorder players in Taiwan others mentioned in this issue (page 26). Numerous studies tout the benefits to Music Reviews. 26 a mature person who plays music, but now Baroque works, plus others by Fulvio Caldini there is a study that outlines measurable benefits for the listener, as well (page 6). As I President’s Message . 3 write these words, it’s Hospice and Palliative ARS President David Podeschi on the Care Month. -

Varieties of History and Their Porous Frontiers

Varieties of History and Their Porous Frontiers Varieties of History and Their Porous Frontiers By R.C. Richardson Varieties of History and Their Porous Frontiers By R.C. Richardson This book first published 2021 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2021 by R.C. Richardson All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-6982-9 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-6982-9 Dedicated to the memory of the Very Revd James Atwell (1946-2020), much loved and inspiring former Dean of Winchester Cathedral, and good friend TABLE OF CONTENTS Permissions ................................................................................................. ix List of Illustrations ...................................................................................... x Preface ........................................................................................................ xi Chapter One ................................................................................................. 1 John Bruen of Stapleford (1560-1625) and his Biographer Chapter Two .............................................................................................. 21 Town -

Witney, Woodstock and Chipping Norton Area Review WITNEY AND

Witney, Woodstock and Chipping Norton Area Review Parishes/Towns and services affected Note: only the contracts in this review are listed – other routes may serve a given parish/town but these are either operated commercially or, if supported, are included in another review area. WITNEY AND WOODSTOCK AREA SERVICES Service Route Parishes/Towns served Divisions affected number Operating days 11 Witney – Oxford City, North Hinksey, N.Hinksey Freeland – Cumnor, Eynsham, Freeland, Jericho & Osney Oxford Hanborough, North Leigh, Eynsham Mon-Sat Witney Hanborough & Minster Lovell Witney S & C Witney N & E 18 Oxford – Oxford City, Cassington, St Margarets Standlake – Eynsham, Stanton Harcourt, Jericho & Osney Bampton Northmoor, Standlake, Aston Eynsham Mon-Sat Cote Shifford & Chimney, Wolvercote & Ducklington, Witney, Bampton, Summertown Clanfield Kidlington S Witney West & Bampton 19 Carterton – Carterton, Alvescot, Black Witney West & Bampton Bampton – Witney Bourton, Clanfield, Bampton, Witney S & C Mon-Sat Aston Cote Shifford & Chimney, Eynsham Ducklington, Standlake (serves Carterton S & W Brighthampton), Witney Burford and Carterton N 64 Carterton – Witney, Curbridge and Lew, Witney S & C Lechlade – Carterton, Alvescot, Kencot, Burford & Carterton N Swindon Filkins, Langford, Little Carterton S & W Mon-Sat Faringdon, Coleshill, Buscot, Faringdon Lechlade & Highworth (Gloucestershire C.C), Swindon BC 113 Burford – Carterton, Shilton, Burford, Burford & Carterton N Carterton – Fulbrook, Faringdon, Alvescot, Carterton S & W Faringdon Clanfield -

Corrina Hewat Reviews

Corrina Hewat | reviews | My Favourite Place Footstompin Music FSR1719 (2003) After 10 years as a full-time musician, and having already appeared on albums by some 20 different artists and groups, Scottish harpist and singer Corrina Hewat hasn't exactly rushed into releasing her debut solo CD but she's not been idle, either, emerging as a performer, composer, arranger and tutor of equal note, with a touring schedule that's taken her across three continents. She's also been a key figure in several landmark Scottish ventures of recent years, including the 2002 Scottish Women tour, Linn Record’s Complete Works of Robert Burns series, and the 31-strong Unusual Suspects concert at this year's Celtic Connections festival. The central trait unifying Hewat's multiple gifts is her fondness and facility for exploring interfaces -- chiefly between folk and jazz, but also in among blues, soul and classical influences. All this breadth of experience and style finds marvellously concentrated yet spacious expression on My Favourite Place complemented by David Milligan on piano, percussionist Donald Hay, and Karine Polwart's backing harmonies. On the vocal front, tracks range from a bold, spiky updating of Sheath And Knife to an understated take on the jazz standard When I Dream. Hewat's own compositions -- such as the brilliantly wayward Traffic and the soulful, title track -- feature prominently among the tunes, together with a handful of beautifully wrought traditional numbers. Sue Wilson The Sunday Herald As soon as I started to listen to Corrina’s beautiful debut solo CD – a delicious, mellow, richly satisfying fusion of jazz/roots/blues styles (pure magic to a person of my musical tastes!), I was immediately transported to my very own ‘favourite place’. -

Dance and Teachers of Dance in Eighteenth-Century Bath

DANCE AND TEACHERS OF DANCE IN EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY BATH Trevor Fawcett Compared with the instructor in music, drawing, languages, or any other fashionable accomplishment, the dancing master (and, in time, his female counterpart) enjoyed an oddly ambiguous status in 18th-century society. Seldom of genteel birth himself, and by education and fortune scarcely fit to rank even with the physician or the clergyman, he found himself the acknowledged expert and authority in those very social graces that were sup posedly the mark and birthright of the polite world alone. Ostensibly he taught dance technique: the execution of the minuet and formal dances, the English country dances in all their variants, the modish cotillion, and the late-century favourites - the Scottish and Irish steps. But while for his pupils a mastery of these skills was indeed a necessary prelude to the ballroom, the fundamental importance of a dancing master lay in the coaching he provided in etiquette, in deportment, and in the cultivation of that air of relaxed assurance so much admired by contemporaries. There was general agreement with John Locke's view that what counted most in dancing was not learning the figures and 'the jigging part' but acquiring an apparent total naturalness, freedom and ease in bodily movement. Clumsiness equated with boorish ness, vulgarity, rusticity, bad manners, bad taste. On several occasions the influential, taste-forming Spectator saw fit to remind its readers about the value of dancing, 'at least, as belongs to the Behaviour and an handsom Carriage of the Body'. Graceful manners and agreeable address ranked among the most reliable indicators of good breeding, and it was 'the proper Business of a Dancing-Master to regulate these Matters' .1 In theory, it might have been argued, only the more humbly born social aspirants 28 TREVOR FAWCETT ought to have needed the services of 'those great polishers of our manners', the dancing masters. -

The Pipe and Tabor

The magazine of THE COUN1RY DANCE SOCIETY OF AMERICA Calendar of Events EDI'roR THE May Gadd April 4 - 6, 1963 28th ANNUAL MOUNTAIN FOLPt: FESTIVAL, Berea, Ky. ASSOCIATE EDI'roR :tV'.ia.y 4 C.D.s. SffiiNJ FESTIVAL, Hunter College, counTRY A.C. King New York City. DAnCER CONTRIBUTING EDI'roRS l'ia.Y 17 - 19 C.D.S. SPROO DANCE WEEKEND, Hudson Lee Haring }~rcia Kerwit Guild Farm, Andover, N.J. Diana Lockard J .Donnell Tilghman June 28 - July 1 BOSTON C.D.S.CENI'RE DAM::E WEEKEND Evelyn K. \'/ells Roberta Yerkes at PINEWOODS, Buzzards Bay, Masa. ART .EDI'roR NATIONAL C.D.S. P:niDIOOJlS CAMP Genevieve Shimer August 4 - 11 CHAMBER MUSIC WEEK) Buzzards August 11 - 25 'lWO DANCE WEEKS ) Bay, THE COUNTRY DANC:lli is published twice a year. Subscription August 25 - Sept.l FOLK MUSIC WEEK ) Hass. is by membership in the Country Dance Society of America (annual dues $5,educational institutions and libraries $3) marriages Inquiries and subscriptions should be sent to the Secretary Country Dance Society of America, 55 Christopher St. ,N.Y .1.4 COMBS-ROGERS: On December 22, 1962, in Pine Mountain,Ky., Tel: ALgonquin 5-8895 Bonnie Combs to Chris Rogers • DAVIS-HODGKIN: On January 12, 196.3, in Germantown, Pa., Copyright 1963 by the Count17 Dance Society Inc. Elizabeth Davis to John P. Hodgkin. CORNWELL-HARING: On January 19, 196.3, in New York City, Table of Contents Margery R. Cornwell to Lee Haring. Page Births CalPndar of Events • • • • • • • • 3 AVISON: To Lois and Richard Avison of Chapleau,Ont., Marriages and Births • • • • • • • .3 on August 7, 1962, a daughter, SHANNON.