Varieties of History and Their Porous Frontiers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Original Lists of Persons of Quality, Emigrants, Religious Exiles, Political

Cornell University Library The original of tiiis book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924096785278 In compliance with current copyright law, Cornell University Library produced this replacement volume on paper that meets the ANSI Standard Z39.48-1992 to replace the irreparably deteriorated original. 2003 H^^r-h- CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME OF THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND GIVEN IN 1891 BY HENRY WILLIAMS SAGE : ; rigmal ^ist0 OF PERSONS OF QUALITY; EMIGRANTS ; RELIGIOUS EXILES ; POLITICAL REBELS SERVING MEN SOLD FOR A TERM OF YEARS ; APPRENTICES CHILDREN STOLEN; MAIDENS PRESSED; AND OTHERS WHO WENT FROM GREAT BRITAIN TO THE AMERICAN PLANTATIONS 1600- I 700. WITH THEIR AGES, THE LOCALITIES WHERE THEY FORMERLY LIVED IN THE MOTHER COUNTRY, THE NAMES OF THE SHIPS IN WHICH THEY EMBARKED, AND OTHER INTERESTING PARTICULARS. FROM MSS. PRESERVED IN THE STATE PAPER DEPARTMENT OF HER MAJESTY'S PUBLIC RECORD OFFICE, ENGLAND. EDITED BY JOHN CAMDEN HOTTEN. L n D n CHATTO AND WINDUS, PUBLISHERS. 1874, THE ORIGINAL LISTS. 1o ihi ^zmhcxs of the GENEALOGICAL AND HISTORICAL SOCIETIES OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, THIS COLLECTION OF THE NAMES OF THE EMIGRANT ANCESTORS OF MANY THOUSANDS OF AMERICAN FAMILIES, IS RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED PY THE EDITOR, JOHN CAMDEN HOTTEN. CONTENTS. Register of the Names of all the Passengers from London during One Whole Year, ending Christmas, 1635 33, HS 1 the Ship Bonavatture via CONTENTS. In the Ship Defence.. E. Bostocke, Master 89, 91, 98, 99, 100, loi, 105, lo6 Blessing . -

History in the Making Annual Report & Accounts 2017 Contents

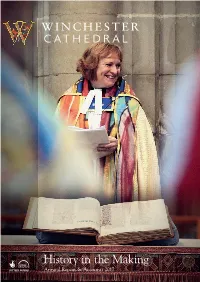

History in the Making Annual Report & Accounts 2017 Contents The Dean 3 The Receiver General 5 Worship 6 Education & Spirituality 8 Canon Principal 8 A Year in View 10 The Lay Canons 12 The Cathedral Council 13 Head of Personnel 13 Architect 14 Archaeologist 14 Winchester Cathedral Enterprises Ltd. 15 Volunteering 15 Financial Report 16 The 2017 Statutory Report and Accounts are available to download from the Cathedral website and, on request, from the Cathedral Office (see back page for contact details). Front Cover: The Dean with The Winchester Bible at her installation on 11 February 2017. Images used in this report are © The Dean and Chapter of Winchester, The Diocese of Winchester, Joe Low, Dominic Parkes and Katherine Davies The Dean The historic dignity and stunning beauty of Around prayer and worship the Cathedral hosts Winchester Cathedral and its music and an increasing number of special services to serve liturgy were fully displayed on the day of my the wider communities of city, county and Installation as 38th Dean of Winchester, on diocese and visits from schools, individuals and Saturday 11 February 2017, by the Bishop of associations, including both tourists and pilgrims. Winchester. The generous welcome from None of this would be possible without the Cathedral, Diocese and County and the presence selfless work of staff and volunteers, both lay of Cathedral partners from Namirembe, and ordained. I am profoundly grateful for the Stavanger and Newcastle were deeply impressive. commitment that so many show to caring for, and The theme of Living Water flowed through the growing, the life and ministry of this place. -

Winchester Cathedral Record 2020 Number 89

Winchester Cathedral Record 2020 Number 89 Friends of Winchester Cathedral 2 The Close, Winchester, Hampshire SO23 9LS 01962 857 245 [email protected] www.winchester-cathedral.org.uk Registered Charity No. 220218 Friends of Winchester Cathedral 2020 Royal Patron Her Majesty the Queen Patron The Right Reverend Tim Dakin, Bishop of Winchester President The Very Reverend Catherine Ogle, Dean of Winchester Ex Officio Vice-Presidents Nigel Atkinson Esq, HM Lord Lieutenant of Hampshire Cllr Patrick Cunningham, The Right Worshipful, the Mayor of Winchester Ms Jean Ritchie QC, Cathedral Council Chairman Honorary Vice-President Mo Hearn BOARD OF TRUSTEES Bruce Parker, Chairman Tom Watson, Vice-Chairman David Fellowes, Treasurer Jenny Hilton, Natalie Shaw Nigel Spicer, Cindy Wood Ex Officio Chapter Trustees The Very Reverend Catherine Ogle, Dean of Winchester The Reverend Canon Andy Trenier, Precentor and Sacrist STAFF Lucy Hutchin, Director Lesley Mead Leisl Porter Friends’ Prayer Most glorious Lord of life, Who gave to your disciples the precious name of friends: accept our thanks for this Cathedral Church, built and adorned to your glory and alive with prayer and grant that its company of Friends may so serve and honour you in this life that they come to enjoy the fullness of your promises within the eternal fellowship of your grace; and this we ask for your name’s sake. Amen. Welcome What we have all missed most during this dreadfully long pandemic is human contact with others. Our own organisation is what it says in the official title it was given in 1931, an Association of Friends. -

The Reformation of the Generations: Age, Ancestry and Memory in England 1500-1700

The Reformation of the Generations: Age, Ancestry and Memory in England 1500-1700 Folger Shakespeare Library Spring Semester Seminar 2016 Alexandra Walsham (University of Cambridge): [email protected] The origins, impact and repercussions of the English Reformation have been the subject of lively debate. Although it is now widely recognised as a protracted process that extended over many decades and generations, surprisingly little attention has been paid to the links between the life cycle and religious change. Did age and ancestry matter during the English Reformation? To what extent did bonds of blood and kinship catalyse and complicate its path? And how did remembrance of these events evolve with the passage of the time and the succession of the generations? This seminar will investigate the connections between the histories of the family, the perception of the past, and England’s plural and fractious Reformations. It invites participants from a range of disciplinary backgrounds to explore how the religious revolutions and movements of the period shaped, and were shaped by, the horizontal relationships that early modern people formed with their sibilings, relatives and peers, as well as the vertical ones that tied them to their dead ancestors and future heirs. It will also consider the role of the Reformation in reconfiguring conceptions of memory, history and time itself. Schedule: The seminar will convene on Fridays 1-4.30pm, for 10 weeks from 5 February to 29 April 2016, excluding 18 March, 1 April and 15 April. In keeping with Folger tradition, there will be a tea break from 3.00 to 3.30pm. -

Congregational History Society Magazine

ISSN 9B?>–?;<> Congregational History Society Magazine Volume ? Number < Spring ;9:: ISSN 0965–6235 THE CONGREGATIONAL HISTORY SOCIETY MAGAZINE Volume E No B Spring A?@@ Contents Editorial 106 News and Views 106 Correspondence 107 The Hampton Court Conference, the King James Version 108 and the Separatists Alan Argent Locals and Cosmopolitans: Congregational Pastors 124 in Edwardian Hampshire Roger Ottewill The Evangelical Union Academy 138 W D McNaughton Reviews 144 Congregational History Society Magazine, Vol. 6, No 3, 2011 105 EDITORIAL In this issue Roger Ottewill conducts readers to Edwardian Hampshire to meet the county’s Congregational pastors, both local, cosmo-local and cosmopolitan (all terms he explains), among whom we find the influential Welsh wizard, J D Jones of Bournemouth, called “the arch-wangler of Nonconformity” by David Lloyd George, who knew a thing or two about wangling. We travel north of the border to study that understated contribution to Scottish Congregationalism, the Evangelical Union, explicitly through its academy. Lastly, like many others in 2011, we turn aside to mark the 400th anniversary of the King James Version of the Bible. In this magazine, our examination of this Jacobean masterpiece involves a consideration of its origins, amid the demands for further reform of the established church, and the growth of those forerunners of Congregationalism, the English separatists. NEWS AND VIEWS We were saddened to learn of the death of John Taylor, for many years the editor of the Transactions of the Congregational Historical Society and, after 1972, of its successor and our sister journal, the Journal of the United Reformed Church History Society . -

The King James Bible

Chap. iiii. The Coming Forth of the King James Bible Lincoln H. Blumell and David M. Whitchurch hen Queen Elizabeth I died on March 24, 1603, she left behind a nation rife with religious tensions.1 The queen had managed to govern for a lengthy period of almost half a century, during which time England had become a genuine international power, in part due to the stabil- ity Elizabeth’s reign afforded. YetE lizabeth’s preference for Protestantism over Catholicism frequently put her and her country in a very precarious situation.2 She had come to power in November 1558 in the aftermath of the disastrous rule of Mary I, who had sought to repair the relation- ship with Rome that her father, King Henry VIII, had effectively severed with his founding of the Church of England in 1532. As part of Mary’s pro-Catholic policies, she initiated a series of persecutions against various Protestants and other notable religious reformers in England that cumu- latively resulted in the deaths of about three hundred individuals, which subsequently earned her the nickname “Bloody Mary.”3 John Rogers, friend of William Tyndale and publisher of the Thomas Matthew Bible, was the first of her victims. For the most part, Elizabeth was able to maintain re- ligious stability for much of her reign through a couple of compromises that offered something to both Protestants and Catholics alike, or so she thought.4 However, notwithstanding her best efforts, she could not satisfy both groups. Toward the end of her life, with the emergence of Puritanism, there was a growing sense among select quarters of Protestant society Lincoln H. -

KJV 400 Years Contents the Thank God for the King James Bible 1 Founders Tom Ascol

FOUNDERS JOURNAL FROM FOUNDERS MINISTRIES | FALL 2011 | ISSUE 86 KJV 400 Years Contents The Thank God for the King James Bible 1 Founders Tom Ascol “Zeal to Promote the Common Good” The Story of the King James Bible 2 Journal Michael A. G. Haykin Committed to historic Baptist principles The Geneva Bible and Its Influence on the King James Bible 16 Matthew Barrett Issue 86 Fall 2011 Excerpts to the Translator’s Preface to the KJV 1611 29 News 15 Review of The Pilgrim’s Progress: A Docudrama 32 Ken Puls KJV 400 Years CONTRIBUTORS: Dr Tom Ascol is Senior Pastor of Grace Baptist Church in Cape Coral, FL and author of the Founders Ministries Blog: http://blog.founders.org/ Matthew Barrett is a PhD candidate at Te Southern Baptist Teological Seminary, Louisville, KY. Dr Michael Haykin is Professor of Church History and Biblical Spirituality at Te Southern Baptist Teological Seminary in Louisville, KY. Cover photo by Ken Puls TheFounders Journal Editor: Thomas K. Ascol Associate Editor: Tom J. Nettles Design Editor: Kenneth A. Puls Contributing Editors: Bill Ascol, Timothy George, Fred Malone, Joe Nesom, Phil Newton, Don Whitney, Hal Wynn. The Founders Journal is a quarterly publication which takes as its theological framework the first recognized confession of faith which Southern Baptists produced, The Abstract of Principles. See page 1 for important subscription information. Please send all inquiries and correspondence to: [email protected] Or you may write to: )/(,-5 )/,(&5R5885)25gkfoig5R5*5),&65 5iiogk Or contact us by phone at (239) 772-1400 or fax at (239) 772-1140. -

The Elizabethan Protestant Press: a Study of the Printing and Publishing of Protestant Literature in English

THE ELIZABETHAN PROTESTANT PRESS: A STUDY OF THE PRINTING AND PUBLISHING OF PROTESTANT RELIGIOUS LITERATURE IN ENGLISH, EXCLUDING BIBLES AND LITURGIES, 1558-1603. By WILLIAN CALDERWOOD, M.A., B.D. Submitted for the Ph.D. degree, University College. (c\ (LONBI 2 ABSTRACT Uninterrupted for forty-five years, from 1558 to 1603, Protestants in England were able to use the printing press to disseminate Protestant ideology. It was a period long enough for Protestantism to root itself deeply in the life of the nation and to accumulate its own distinctive literature. English Protestantism, like an inf ant vulnerable to the whim of a parent under King Henry VIII, like a headstrong and erratic child in Edward's reign, and like a sulking, chastised youth in the Marian years, had come of age by the end of the Elizabethan period. At the outset of Elizabeth's reign the most pressing religious need was a clear, well-reasoned defence of the Church of England. The publication of Bishop Jewel's Apologia Ecclesiae Anglicanae in 1562 was a response to that need and set the tone of literary polemics for the rest of the period. It was a time of muscle- flexing for the Elizabethan Church, and especially in the opening decades, a time when anti-Catholicism was particularly vehement. Consistently throughout the period, when Queen and country were threatened by Catholic intrigues and conspiracies, literature of exceptional virulence was published against Catholicism. But just as the press became an effective tool for defenders and apologists of the Church of England, it soon was being used as an instrument to advance the cause of further reform by more radical Protestants. -

University of Birmingham Revising the King James Apocrypha

University of Birmingham Revising the King James Apocrypha Hardy, Nicholas DOI: 10.1163/9789004359055_009 License: None: All rights reserved Document Version Peer reviewed version Citation for published version (Harvard): Hardy, N 2018, Revising the King James Apocrypha: John Bois, Isaac Casaubon, and the Case of 1 Esdras. in M Feingold (ed.), Labourers in the Vineyard of the Lord: Scholarship and the Making of the King James Version of the Bible. Scientific and Learned Cultures and Their Institutions, Brill, Leiden, pp. 266-327. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004359055_009 Link to publication on Research at Birmingham portal Publisher Rights Statement: The institute employing the author may post the post-refereed, but pre-print version of that article as appearing in multi-authored books free of charge on its website. Policy see http://www.brill.com/resources/authors/publishing-books-brill/self-archiving-rights General rights Unless a licence is specified above, all rights (including copyright and moral rights) in this document are retained by the authors and/or the copyright holders. The express permission of the copyright holder must be obtained for any use of this material other than for purposes permitted by law. •Users may freely distribute the URL that is used to identify this publication. •Users may download and/or print one copy of the publication from the University of Birmingham research portal for the purpose of private study or non-commercial research. •User may use extracts from the document in line with the concept of ‘fair dealing’ under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (?) •Users may not further distribute the material nor use it for the purposes of commercial gain. -

Educator-2012-1St-Trimestermres

Volume LXXVI, No. 1 • January –April 2012 Total 2011 Fall Enrollment at the 51 IABCU Schools: 153,800 Undergraduate: 122,883; Graduate: 30,917 UNDERGRADUATE GRADUATE UNDERGRADUATE GRADUATE 1. Anderson University 2,727 250 29. Judson College 348 — 2. Arkansas Baptist College 1,193 — 30. Judson University 1,200 — 3. The Baptist College of Florida 652 __ 31. Louisiana College (level 3 grad, prog.) 1,157 426 4. Baptist College of Health Sciences 975 __ 32. Mercer University 4,409 3,927 5. Baptist University of the Americas 750 33. Mid-Continent University 2,472 — (with off campus centers) — 34. Mississippi College 3,200 2,018 6. Baylor University 12,575 2,454 35. Missouri Baptist University 3,842 1,359 7. Belmont University 5,004 1,370 36. North Greenville University 2,200 238 8. Blue Mountain College 555 — 37. Oklahoma Baptist University 1,802 9. Bluefield College 760 — 38. Ouachita Baptist University 1,594 — 10. Bowen University (Nigeria) 4,500 39. Samford University 2,950 1,808 11. Brewton-Parker College 1,030 — 40. Seinan Gakuin University (Japan) 7,942 219 12. California Baptist University 4,403 1,010 41. Shorter University 3,240 250 13. Campbell University 4,994 1,030 (including adult degree students) (first professional enrollment 1128) 42. Southwest Baptist University 2,872 761 14. Campbellsville University 3,607 535 43. Union University 3,025 1,180 15. Carson-Newman College 1,686 284 44. University of the Cumberlands 1,762 2,023 16. Charleston Southern University 2,917 378 45. University of Mary Hardin-Baylor 2,784 353 17. -

Annual Report

ANNUAL REPORT STATUTORY SUPPLEMENT AND AUDITED ACCOUNTS FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 MARCH 2014 The Cathedral Church of the Holy Trinity, St Peter and St Paul, and of St Swithun in Winchester Annual Report Statutory Supplement and Audited Accounts 2013/14 Contents 111 Aims and Objectives .................................................................................................. 3 222 Chapter Reports ........................................................................................................ 4 2.1 The Dean .......................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 4 2.2 The Receiver General ................................................................................................................................................................................................. 5 2.3 Worship ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 6 2.4 Education and Spirituality ........................................................................................................................................................................................ 7 333 Legal and administrative information ......................................................................... 9 3.1 Legal name of the Cathedral -

Building Performance

Building Performance Environmental assessments to support the use and development of cathedrals and church buildings Cathedrals are complex buildings typically incorporating not only a church constructed over many years, but also ancillary structures of various periods and functions. To fulfil the Church’s mission, these buildings must support a vast range of activities; from worship, education and community support, to tourism and the display of museum-quality collections. This imposes great technical demands and at times conservation may conflict with use. Building performance assessment is a critical tool to successful management, bringing together information not only about the fabric and the microclimate, but also about the services (especially the heating), and current and future uses. By understanding how a building is performing, day-to-day management can be more effective, care and conservation can be more sustainable, and the risks and running costs of alterations minimised. This conference brings together a range of experts, to explore the assessment of building performance and the control of internal microclimates. It will include a forum to discuss ways of making such assessments possible, and of sharing information and experience. The focus will be on the complex case of cathedrals, but it will also be of interest to those working with environmental problems in greater churches, smaller parish churches, and other types of historic buildings. Date: 2 October 2014 Venue: Mercers’ Hall | Ironmonger Lane | London | EC2V 8HE