Patient-Controlled Analgesia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacology of Drugs Used in Children

Drug and Fluid Th erapy SECTION II Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacology of Drugs Used CHAPTER 6 in Children Charles J. Coté, Jerrold Lerman, Robert M. Ward, Ralph A. Lugo, and Nishan Goudsouzian Drug Distribution Propofol Protein Binding Ketamine Body Composition Etomidate Metabolism and Excretion Muscle Relaxants Hepatic Blood Flow Succinylcholine Renal Excretion Intermediate-Acting Nondepolarizing Relaxants Pharmacokinetic Principles and Calculations Atracurium First-Order Kinetics Cisatracurium Half-Life Vecuronium First-Order Single-Compartment Kinetics Rocuronium First-Order Multiple-Compartment Kinetics Clinical Implications When Using Short- and Zero-Order Kinetics Intermediate-Acting Relaxants Apparent Volume of Distribution Long-Acting Nondepolarizing Relaxants Repetitive Dosing and Drug Accumulation Pancuronium Steady State Antagonism of Muscle Relaxants Loading Dose General Principles Central Nervous System Effects Suggamadex The Drug Approval Process, the Package Insert, and Relaxants in Special Situations Drug Labeling Opioids Inhalation Anesthetic Agents Morphine Physicochemical Properties Meperidine Pharmacokinetics of Inhaled Anesthetics Hydromorphone Pharmacodynamics of Inhaled Anesthetics Oxycodone Clinical Effects Methadone Nitrous Oxide Fentanyl Environmental Impact Alfentanil Oxygen Sufentanil Intravenous Anesthetic Agents Remifentanil Barbiturates Butorphanol and Nalbuphine 89 A Practice of Anesthesia for Infants and Children Codeine Antiemetics Tramadol Metoclopramide Nonsteroidal Anti-infl ammatory Agents 5-Hydroxytryptamine -

Accidental Awareness During General Anaesthesia (AAGA) in Obstetrics

O B S T E T R I C A N A E S T H E S I A Tutorial 388 Accidental Awareness during General Anaesthesia (AAGA) in Obstetrics Dr. Rezaur Rahman Specialty Registrar in Anaesthetics, Queen Alexandra Hospital, Portsmouth, United Kingdom Dr. Samantha Wilson Consultant Anaesthetist, Basingstoke and North Hampshire Hospital, Basingstoke, United Kingdom Edited by Dr James Brown,i Dr Gill Abirii i Consultant Anesthesiologist, BC Women’s Hospital, Canada ii Clinical Associate Professor, Stanford University School of Medicine, USA nd Correspondence to [email protected] 2 Oct 2018 An online test is available for self-directed Continuous Medical Education (CME). A certificate will be awarded upon passing the test. Please refer to the accreditation policy here. Take online quiz KEY POINTS Accidental awareness during general anaesthesia is more common in obstetric practice than in any other discipline of anaesthesia Factors contributing to an increased risk of accidental awareness during general anaesthesia include maternal stress or anxiety, emergency surgery and the “intravenous-inhalational” interval Accidental awareness during general anaesthesia can be associated with considerable physiological and psychological harm Strategies to minimise the risk of accidental awareness during general anaesthesia include an appropriate dose of anaesthetic induction agent, and use of nitrous oxide to achieve an adequate depth of anaesthesia INTRODUCTION Accidental awareness during general anaesthesia (AAGA) is defined as the unintended experience and subsequent recall of intra-operative events. In recent decades, the incidence of AAGA has been reported as between 1–2:1,000 general anaesthetics (1). The landmark NAP5 report (Fifth National Audit Project) - a national survey conducted by The Royal College of Anaesthetists (RCOA) which investigated spontaneous reports of AAGA - demonstrated an incidence of 1:19,000 in the general population. -

Inhalational Anesthetics

UPTAKE AND DISTRIBUTION OF INHALATIONAL ANESTHETICS Dr.J.Edward Johnson.M.D.(Anaes),D.C.H. Asst.Professor, Kanyakumari Govt. Medical College Hospital. INTRODUCTION The modern anesthetist expeditiously develops and then sustains anesthetic concentrations in the central nervous system that are sufficient for surgery with agents and techniques that usually permit rapid recovery from anesthesia. Understanding the factors that govern the relationship between the delivered anesthetic and brain concentrations enhances the optimum conduct of anesthesia. I. UPTAKE OF INHALED ANESTHETICS. A. Factors raising the alveolar concentration, assuming a constant inspired anesthetic concentration, and no uptake by blood: 1. The inspired concentration (FI). a. The rate of rise is directly proportional to the inspired concentration. 2. The alveolar ventilation (Valveolar) a. The larger the minute alveolar ventilation (Valveolar), the more rapid the rise in alveolar concentration (FA) . b. Inspired gas is diluted by the FRC, so the larger the FRC, as a fraction of Valveolar, the slower the alveolar rise in anesthetic concentration. c. For ventilatory rates over 4 breaths, the ventilatory rate does not make any difference at the same Valveolar. 3. The time constant The time required for flow through a container to equal the capacity of the container. Time constant = volume (capacity)/flow Time Constant % washin/washout 1 63% 2 86% 3 95% 4 98% For example; If 10 liter box is initially filled with oxygen and 5 l/min of nitrogen flow into box then, the TC is volume (capacity)/flow. TC = 10 / 5 = 2 minutes. So, the nitrogen concentration at end of 2 minutes is 63%. -

Midazolam Injection, USP

Midazolam Injection, USP Rx only PHARMACY BULK PACKAGE – NOT FOR DIRECT INFUSION WARNING ADULTS AND PEDIATRICS: Intravenous midazolam has been associated with respiratory depression and respiratory arrest, especially when used for sedation in noncritical care settings. In some cases, where this was not recognized promptly and treated effectively, death or hypoxic encephalopathy has resulted. Intravenous midazolam should be used only in hospital or ambulatory care settings, including physicians’ and dental offices, that provide for continuous monitoring of respiratory and cardiac function, i.e., pulse oximetry. Immediate availability of resuscitative drugs and age- and size-appropriate equipment for bag/valve/mask ventilation and intubation, and personnel trained in their use and skilled in airway management should be assured (see WARNINGS). For deeply sedated pediatric patients, a dedicated individual, other than the practitioner performing the procedure, should monitor the patient throughout the procedures. The initial intravenous dose for sedation in adult patients may be as little as 1 mg, but should not exceed 2.5 mg in a normal healthy adult. Lower doses are necessary for older (over 60 years) or debilitated patients and in patients receiving concomitant narcotics or other central nervous system (CNS) depressants. The initial dose and all subsequent doses should always be titrated slowly; administer over at least 2 minutes and 1 allow an additional 2 or more minutes to fully evaluate the sedative effect. The dilution of the 5 mg/mL formulation is recommended to facilitate slower injection. Doses of sedative medications in pediatric patients must be calculated on a mg/kg basis, and initial doses and all subsequent doses should always be titrated slowly. -

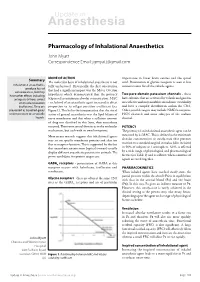

Pharmacology of Inhalational Anaesthetics John Myatt Correspondence Email: [email protected]

Update in Anaesthesia Pharmacology of Inhalational Anaesthetics John Myatt Correspondence Email: [email protected] MODE OF ACTION Summary importance in lower brain centres and the spinal The molecular basis of inhalational anaesthesia is not cord. Potentiation of glycine receptors is seen at low Inhalational anaesthetics fully understood. Historically, the first observation concentrations for all the volatile agents. produce loss of consciousness, but may that had a significant impact was the Meyer-Overton Two-pore-domain potassium channels have other effects including hypothesis which demonstrated that the potency - these analgesia (nitrous oxide) (expressed as minimum alveolar concentration, MAC have subunits that are activated by volatile and gaseous or muscle relaxation - see below) of an anaesthetic agent increased in direct anaesthetics and may modulate membrane excitability (isoflurane). They are proportion to its oil:gas partition coefficient (see and have a complex distribution within the CNS. presented as liquefied gases Figure 1). This led to the interpretation that the site of Other possible targets may include NMDA receptors, under pressure or as volatile action of general anaesthetics was the lipid bilayer of HCN channels and some subtypes of the sodium liquids. nerve membranes and that when a sufficient amount channel. of drug was dissolved in this layer, then anaesthesia occurred. There were several theories as to the molecular POTENCY mechanism, but each with its own limitations. The potency of an inhalational anaesthetic agent can be More recent research suggests that inhalational agents measured by its MAC. This is defined as the minimum may act on specific membrane proteins and alter ion alveolar concentration at steady-state that prevents flux or receptor function. -

Performance of Anesthetic Depth Indexes in Rabbits Under Propofol Anesthesia Prediction Probabilities and Concentration-Effect Relations

Performance of Anesthetic Depth Indexes in Rabbits under Propofol Anesthesia Prediction Probabilities and Concentration-effect Relations Aura Silva, M.Sc.,* So´ nia Campos, M.Sc.,† Joaquim Monteiro, Ph.D.,‡ Carlos Venaˆ ncio, M.Sc.,* Bertinho Costa, Ph.D.,§ Paula Guedes de Pinho, Ph.D.,ʈ Luis Antunes, Ph.D.# Downloaded from http://pubs.asahq.org/anesthesiology/article-pdf/115/2/303/255162/0000542-201108000-00017.pdf by guest on 30 September 2021 ABSTRACT What We Already Know about This Topic • A number of electroencephalogram-based measures have Background: The permutation entropy, the approximate been studied to determine their usefulness for intraoperative entropy, and the index of consciousness are some of the most monitoring of anesthetic depth • recently studied electroencephalogram-derived indexes. In In rats anesthetized with a potent volatile anesthetic, burst suppression-corrected permutation entropy had the best cor- this work, a thorough comparison of these indexes was per- relation with anesthetic dose formed using propofol anesthesia in a rabbit model. Methods: Six rabbits were anesthetized with three propofol Ϫ Ϫ infusion rates: 70, 100, and 130 mg ⅐ kg 1 ⅐ h 1, each main- tained for 30 min, in a random order for each animal. What This Article Tells Us That Is New Data recording was performed in the awake animals 20, • In rabbits receiving propofol by infusion, burst suppression- 25, and 30 min after each infusion rate was begun in the corrected permutation entropy and burst suppression-cor- rected composite multiscale permutation entropy had the recovered animals and consisted of electroencephalogram best propofol concentration-effect relationships and predic- recordings, evaluation of depth of anesthesia according to a clinical tions of clinical signs scale, and arterial blood samples for plasma propofol determination. -

Nitrous Oxide Diffusion and the Second Gas Effect on Emergence from Anesthesia

Nitrous Oxide Diffusion and the Second Gas Effect on Emergence from Anesthesia Philip J. Peyton, M.D.,* Ian Chao, M.B.B.S.,† Laurence Weinberg, F.A.N.Z.C.A.,‡ Gavin J. B. Robinson, F.A.N.Z.C.A.,§ Bruce R. Thompson, Ph.D. ABSTRACT What We Already Know about This Topic Downloaded from http://pubs.asahq.org/anesthesiology/article-pdf/114/3/596/253394/0000542-201103000-00026.pdf by guest on 27 September 2021 • The increase in the partial pressures of the other gases in the Background: Rapid elimination of nitrous oxide from the alveolar mixture resulting from the rapid uptake of high con- lungs at the end of inhalational anesthesia dilutes alveolar centrations of nitrous oxide during inhalational anesthesia in- duction is known as the second gas effect. oxygen, producing “diffusion hypoxia.” A similar dilutional effect on accompanying volatile anesthetic agent has not been evaluated and may impact the speed of emergence. Methods: Twenty patients undergoing surgery were ran- What This Article Tells Us That Is New domly assigned to receive an anesthetic maintenance gas • The second gas effect also occurs during emergence, with the mixture of sevoflurane adjusted to bispectral index, in air- rapid removal of nitrous oxide increasing the removal of other oxygen (control group) versus a 2:1 mixture of nitrous oxide- volatile anesthetics. oxygen (nitrous oxide group). After surgery, baseline arterial and tidal gas samples were taken. Patients were ventilated reduction of concentrations of the accompanying volatile with oxygen, and arterial and tidal gas sampling was repeated agents, contributing to the speed of emergence observed after at 2 and 5 min. -

A Comparative Blind Study for Assessment of Intubating Conditions Using Propofol and Remifentanil with and Without Muscle Relaxant

Alexandria Journal of Anaesthesia and Intensive Care A Comparative Blind Study for Assessment of Intubating Conditions Using Propofol and Remifentanil with and Without Muscle Relaxant Dr. Ashraf A. Hassan*,Hefny M Hefny *Department of Anesthesia, Faculty of Medicine, University of Alexandria, Alexandria, Egypt. ABSTRACT Background: Remifentanil is a powerful and ultra-short acting opiate, with a rapid onset of action. It is hydrolyzed by non-specific blood and tissue esterases and it has a half life of approximately 3 min compared with 58.5 min for alfentanil after 4 hours infusion. Thus, remifentanil can be administered without fear of accumulation over time. Intubation without neuromuscular blocking agents has been used in a number of different studies. Based on the pharmacokinetic profile of remifentanil, it was hypothesized that it may be very useful in facilitating tracheal intubation. The aim of our study is to determine the quality of intubation using remifentanil 3µg/kg and propofol 2 mg/kg compared with the standard use of muscle relaxants. Methods: We studied 100 healthy adult patients (ASA physical status I, II), undergoing elective surgery requiring tracheal intubation. They are arranged in two equal groups: one group with muscle relaxation given for intubation, while the other group no relaxant was given. Anesthesia was induced with 3µg.kg-1 of remifentanil over 3 min. followed by propofol 2mg.kg-1 as a bolus over 30 seconds for both groups. Laryngoscopy was performed after assisted ventilation with 50% N2O and 6-8% desflurane in O2till a bispectral index value (BIS) of < 40% was reached. The trachea was intubated with an appropriate-sized cuffed tube. -

Understanding Anesthesia a Learner's Handbook

1ST EDITION Understanding Anesthesia A Learner's Handbook AUTHOR Karen Raymer, MD, MSc, FRCP(C) McMaster University CONTRIBUTING EDITORS Karen Raymer, MD, MSc, FRCP(C) Richard Kolesar, MD, FRCP(C) TECHNICAL PRODUCTION Eric E. Brown, HBSc Karen Raymer, MD, FRCP(C) www.understandinganesthesia.ca Understanding Anesthesia A Learner’s Handbook AUTHOR Dr. Karen Raymer, MD, MSc, FRCP(C) Clinical Professor, Department of Anesthesia, Faculty of Health Sciences, McMaster University CONTRIBUTING EDITORS Dr. Karen Raymer, MD, MSc, FRCP(C) Dr. Richard Kolesar, MD, FRCP(C) Associate Clinical Professor, Department of Anesthesia, Faculty of Health Sciences, McMaster University TECHNICAL PRODUCTION Eric E. Brown, HBSc MD Candidate (2013), McMaster University Karen Raymer, MD, FRCP(C) ISBN 978-0-9918932-1-8 i Preface ii PREFACE Getting the most from your book grams such as Emergency Medicine or Internal Medicine, who re- This handbook arose after the creation of an ibook, entitled, “Un- quire anesthesia experience as part of their training, will also find derstanding Anesthesia: A Learner’s Guide”. The ibook is freely the guide helpful. available for download and is viewable on the ipad. The ibook ver- The book is written at an introductory level with the aim of help- sion has many interactive elements that are not available in a paper ing learners become oriented and functional in what might be a book. Some of these elements appear as spaceholders in this (pa- brief but intensive clinical experience. Those students requiring per) handbook. more comprehensive or detailed information should consult the If you do not have the ibook version of “Understanding Anesthe- standard anesthesia texts. -

The Use of Midazolam, Isoflurane, and Nitrous Oxide for Sedation and Anesthesia of Ball Pythons (Python Regius)

The Use of Midazolam, Isoflurane, and Nitrous Oxide for Sedation and Anesthesia of Ball Pythons (Python regius) by Cédric B. Larouche A Thesis presented to The University of Guelph In partial fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Veterinary Science in Pathobiology Guelph, Ontario, Canada © Cédric B. Larouche, August, 2019 ABSTRACT THE USE OF MIDAZOLAM, ISOFLURANE, AND NITROUS OXIDE FOR SEDATION AND ANESTHESIA OF BALL PYTHONS (PYTHON REGIUS) Cédric B. Larouche Co-advisors: University of Guelph, 2019 Nicole Nemeth Dorothee Bienzle The objectives of this project were to characterize the pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of midazolam in the ball python (Python regius), and to evaluate the effects of midazolam and nitrous oxide (N2O) on the minimum anesthetic concentration of isoflurane (MACIso) in this species. The pharmacodynamics of midazolam were evaluated in a blinded, randomized, crossover study comparing two dosages (1 and 2 mg/kg intramuscular [IM]) in ten ball pythons. There were no significant differences between the two dosages for any parameter evaluated. Midazolam provided moderate sedation and muscle relaxation in all snakes starting 10-15 min post-injection and lasting up to 3-5 days, with a peak effect 60 min post-injection. Heart rates were significantly lower than baseline from 30 min to 5.3 days post-injection with both dosages. In an open trial using 9 ball pythons, the reversal effect of flumazenil was evaluated by administering 0.08 mg/kg IM 60 min after the administration of 1 mg/kg IM of midazolam. Sedation and muscle relaxation were fully reversed within 10 min of administration, but all snakes fully resedated within 3 h. -

Point of Care Intravenous Anaesthetic Measurement in Anaesthesia and Critical Care By

Point of Care Intravenous Anaesthetic Measurement in Anaesthesia and Critical Care by Dr Nicholas John Cowley A Thesis Submitted to The University of Birmingham for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MEDICINE (MD) School of Clinical and Experimental Medicine College of Medicine and Dentistry University of Birmingham Date of Submission: May 2014 i University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Contents Abstract ................................................................................................................. iii List of Chapters ...................................................................................................... v List of Figures ........................................................................................................ xii List of Tables ......................................................................................................... xvii Declaration ........................................................................................................... -

The Effects of Ventilation-Perfusion Scatter on Gas Exchange During Nitrous Oxide Anaesthesia

The effects of ventilation-perfusion scatter on gas exchange during nitrous oxide anaesthesia A thesis submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Dr. Philip John Peyton MD MBBS FANZCA Department of Anaesthesia Austin Hospital and University Department of Surgery Austin Hospital and University of Melbourne 2011 Printed on Archival Quality Paper ii Abstract Nitrous oxide (N2O) is the oldest anaesthetic agent still in clinical use. Due to its weak anaesthetic potency, it is customarily administered at concentrations as high as 70%, in combination with the more potent volatile anaesthetic agents. It allows a dose reduction of these agents and, unlike them, is characterised by remarkable cardiovascular and respiratory stability and has analgesic properties. Its low solubility in blood and body tissues produces rapid washin into the body on induction and rapid washout on emergence at the end of surgery. Its rapid early uptake by the lungs is known to produce a concentrating effect on the accompanying alveolar oxygen (O2) and volatile agent, increasing their alveolar concentration and enhancing their uptake, which speeds induction of anaesthesia. This is called the “second gas effect”. The place of N2O in modern anaesthetic practice has increasingly been criticised. It has a number of potential adverse effects, such as immunosuppression with prolonged exposure, and the possibility of cardiovascular complications due to acute elevation of plasma homocysteine levels is currently being investigated. It has been implicated as a cause of post-operative nausea and vomiting (PONV), and is a greenhouse gas pollutant. Its continued use relies largely on its perceived pharmacokinetic advantages, but these have been questioned.