Chariots” in Contact: on the Value of the Signs *91, *92 and *94 of Hieroglyphic Luwian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cuneiform and Hieroglyphs 11

The Unicode® Standard Version 13.0 – Core Specification To learn about the latest version of the Unicode Standard, see http://www.unicode.org/versions/latest/. Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book, and the publisher was aware of a trade- mark claim, the designations have been printed with initial capital letters or in all capitals. Unicode and the Unicode Logo are registered trademarks of Unicode, Inc., in the United States and other countries. The authors and publisher have taken care in the preparation of this specification, but make no expressed or implied warranty of any kind and assume no responsibility for errors or omissions. No liability is assumed for incidental or consequential damages in connection with or arising out of the use of the information or programs contained herein. The Unicode Character Database and other files are provided as-is by Unicode, Inc. No claims are made as to fitness for any particular purpose. No warranties of any kind are expressed or implied. The recipient agrees to determine applicability of information provided. © 2020 Unicode, Inc. All rights reserved. This publication is protected by copyright, and permission must be obtained from the publisher prior to any prohibited reproduction. For information regarding permissions, inquire at http://www.unicode.org/reporting.html. For information about the Unicode terms of use, please see http://www.unicode.org/copyright.html. The Unicode Standard / the Unicode Consortium; edited by the Unicode Consortium. — Version 13.0. Includes index. ISBN 978-1-936213-26-9 (http://www.unicode.org/versions/Unicode13.0.0/) 1. -

A Translation of the Malia Altar Stone

MATEC Web of Conferences 125, 05018 (2017) DOI: 10.1051/ matecconf/201712505018 CSCC 2017 A Translation of the Malia Altar Stone Peter Z. Revesz1,a 1 Department of Computer Science, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Lincoln, NE, 68588, USA Abstract. This paper presents a translation of the Malia Altar Stone inscription (CHIC 328), which is one of the longest known Cretan Hieroglyph inscriptions. The translation uses a synoptic transliteration to several scripts that are related to the Malia Altar Stone script. The synoptic transliteration strengthens the derived phonetic values and allows avoiding certain errors that would result from reliance on just a single transliteration. The synoptic transliteration is similar to a multiple alignment of related genomes in bioinformatics in order to derive the genetic sequence of a putative common ancestor of all the aligned genomes. 1 Introduction symbols. These attempts so far were not successful in deciphering the later two scripts. Cretan Hieroglyph is a writing system that existed in Using ideas and methods from bioinformatics, eastern Crete c. 2100 – 1700 BC [13, 14, 25]. The full Revesz [20] analyzed the evolutionary relationships decipherment of Cretan Hieroglyphs requires a consistent within the Cretan script family, which includes the translation of all known Cretan Hieroglyph texts not just following scripts: Cretan Hieroglyph, Linear A, Linear B the translation of some examples. In particular, many [6], Cypriot, Greek, Phoenician, South Arabic, Old authors have suggested translations for the Phaistos Disk, Hungarian [9, 10], which is also called rovásírás in the most famous and longest Cretan Hieroglyph Hungarian and also written sometimes as Rovas in inscription, but in general they were unable to show that English language publications, and Tifinagh. -

This Document Serves As a Summary of the UC Berkeley Script Encoding Initiative's Recent Activities. Proposals Recently Submit

L2/11‐049 TO: Unicode Technical Committee FROM: Deborah Anderson, Project Leader, Script Encoding Initiative, UC Berkeley DATE: 3 February 2011 RE: Liaison Report from UC Berkeley (Script Encoding Initiative) This document serves as a summary of the UC Berkeley Script Encoding Initiative’s recent activities. Proposals recently submitted to the UTC that have involved SEI assistance include: Afaka (Everson) [preliminary] Elbasan (Everson and Elsie) Khojki (Pandey) Khudawadi (Pandey) Linear A (Everson and Younger) [revised] Nabataean (Everson) Woleai (Everson) [preliminary] Webdings/Wingdings Ongoing work continues on the following: Anatolian Hieroglyphs (Everson) Balti (Pandey) Dhives Akuru (Pandey) Gangga Malayu (Pandey) Gondi (Pandey) Hungarian Kpelle (Everson and Riley) Landa (Pandey) Loma (Everson) Mahajani (Pandey) Maithili (Pandey) Manichaean (Everson and Durkin‐Meisterernst) Mende (Everson) Modi (Pandey) Nepali script (Pandey) Old Albanian alphabets Pahawh Hmong (Everson) Pau Cin Hau Alphabet and Pau Cin Hau Logographs (Pandey) Rañjana (Everson) Siyaq (and related symbols) (Pandey) Soyombo (Pandey) Tani Lipi (Pandey) Tolong Siki (Pandey) Warang Citi (Everson) Xawtaa Dorboljin (Mongolian Horizontal Square script) (Pandey) Zou (Pandey) Proposals for unencoded Greek papyrological signs, as well as for various Byzantine Greek and Sumero‐Akkadian characters are being discussed. A proposal for the Palaeohispanic script is also underway. Deborah Anderson is encouraging additional participation from Egyptologists for future work on Ptolemaic signs. She has received funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities and support from Google to cover work through 2011. . -

Bryn Mawr Classical Review 2017.08.38

Bryn Mawr Classical Review 2017.08.38 http://bmcr.brynmawr.edu/2017/2017-08-38 BMCR 2017.08.38 on the BMCR blog Bryn Mawr Classical Review 2017.08.38 Paola Cotticelli-Kurras, Alfredo Rizza (ed.), Variation within and among Writing Systems: Concepts and Methods in the Analysis of Ancient Written Documents. LautSchriftSprache / ScriptandSound. Wiesbaden: Dr. Ludwig Reichert Verlag, 2017. Pp. 384. ISBN 9783954901456. €98.00. Reviewed by Anna P. Judson, Gonville & Caius College, University of Cambridge ([email protected]) Table of Contents [Authors and titles are listed at the end of the review.] This book is the first of a new series, ‘LautSchriftSprache / ScriptandSound’, focusing on the field of graphemics (the study of writing systems), in particular historical graphemics. As the traditional view of writing as (merely) a way of representing speech has given way to a more nuanced understanding of writing as a different, rather than secondary, means of communication,1 graphemics has become an increasingly popular field; it is also necessarily an interdisciplinary field, since it incorporates the study not only of written texts’ linguistic features, but also broader aspects such as their visual features, material supports, and contexts of production and reading. A series dedicated to the study of graphemics across multiple academic disciplines is therefore a very welcome development. This first volume presents twenty-one papers from the third ‘LautSchriftSprache’ conference, held in Verona in 2013. In their introduction, the editors stress that the aim is to present studies of writing systems with as wide a scope as possible in terms of location, chronology, writing support, cultural context, and function. -

Name Hierarchy Methods Enums and Flags

Pango::Gravity(3pm) User Contributed Perl Documentation Pango::Gravity(3pm) NAME Pango::Gravity − represents the orientation of glyphs in a segment of text HIERARCHY Glib::Enum +−−−−Pango::Gravity METHODS gravity = Pango::Gravity::get_for_matrix ($matrix) • $matrix (Pango::Matrix) gravity = Pango::Gravity::get_for_script ($script, $base_gravity, $hint) • $script (Pango::Script) • $base_gravity (Pango::Gravity) • $hint (Pango::GravityHint) boolean = Pango::Gravity::is_vertical ($gravity) • $gravity (Pango::Gravity) double = Pango::Gravity::to_rotation ($gravity) • $gravity (Pango::Gravity) ENUMS AND FLAGS enum Pango::Gravity • ’south’ / ’PANGO_GRAVITY_SOUTH’ • ’east’ / ’PANGO_GRAVITY_EAST’ • ’north’ / ’PANGO_GRAVITY_NORTH’ • ’west’ / ’PANGO_GRAVITY_WEST’ • ’auto’ / ’PANGO_GRAVITY_AUTO’ enum Pango::GravityHint • ’natural’ / ’PANGO_GRAVITY_HINT_NATURAL’ • ’strong’ / ’PANGO_GRAVITY_HINT_STRONG’ • ’line’ / ’PANGO_GRAVITY_HINT_LINE’ enum Pango::Script • ’invalid−code’ / ’PANGO_SCRIPT_INVALID_CODE’ • ’common’ / ’PANGO_SCRIPT_COMMON’ • ’inherited’ / ’PANGO_SCRIPT_INHERITED’ • ’arabic’ / ’PANGO_SCRIPT_ARABIC’ • ’armenian’ / ’PANGO_SCRIPT_ARMENIAN’ • ’bengali’ / ’PANGO_SCRIPT_BENGALI’ • ’bopomofo’ / ’PANGO_SCRIPT_BOPOMOFO’ • ’cherokee’ / ’PANGO_SCRIPT_CHEROKEE’ • ’coptic’ / ’PANGO_SCRIPT_COPTIC’ • ’cyrillic’ / ’PANGO_SCRIPT_CYRILLIC’ • ’deseret’ / ’PANGO_SCRIPT_DESERET’ • ’devanagari’ / ’PANGO_SCRIPT_DEVANAGARI’ • ’ethiopic’ / ’PANGO_SCRIPT_ETHIOPIC’ • ’georgian’ / ’PANGO_SCRIPT_GEORGIAN’ perl v5.28.0 2018-10-29 1 Pango::Gravity(3pm) User Contributed -

Writing in Anatolia: the Origins of the Anatolian Hieroglyphs and the Introductions of the Cuneiform Script 1

Altoriental. Forsch., Akademie Verlag, 39 (2012) 2, 287–315 Willemijn Waal Writing in Anatolia: The Origins of the Anatolian Hieroglyphs and the Introductions of the Cuneiform Script 1 Abstract This article argues that the Anatolian hieroglyphic script, which is generally thought to have been an invention of the second half of the second millennium BCE, has its origins already in the late third/early second millennium BCE. The argument that Anatolian hieroglyphs are much older than hitherto assumed is based on a wide array of evidence, such as (signs on) seals and textual data from both Ana- tolia and the Aegean. These data imply that Anatolian hieroglyphs, like virtually any other writing system, started out as a simple pictographic script used for basic economic and administrative records and over time developed into a full-fledged writing system, rather than being ‘invented’ in the Hittite Period. It is demonstrated that the enigmatic is.urtum-documents found in Old Assyrian texts refer to documents written in Ana- tolian hieroglyphs, similar to the gisˇ.hur/US. URTUM/gulzattar documents in the Hittite Period.These docu- ments, which have not been preserved because they were written on the perishable material wood, contained those types of texts that are conspicuously absent from the Old Assyrian and Hittite Periods. Since the Anatolians already had a script of their own, the cuneiform script never became firmly rooted within Anatolian society, and its usage was restricted to certain domains. This would explain why the cuneiform script was introduced (and subsequently abandoned) twice in Bronze Age Anatolia, whereas the Anatolian hieroglyphs continued to be used well into the first millennium BCE. -

The Anatolian Subgroup of Indo-European in the Light of the “Minor” Languages

The Anatolian Subgroup of Indo-European in the Light of the “Minor” Languages H. Craig Melchert Carrboro NC Almost immediately following Bedřich Hrozný’s successful identification of Hittite as an Indo-European language, there was an early recognition that Hittite (Nesite) was not the only Indo-European language in Anatolia. Forrer (1919) already identified Luvian and Palaic as distinct languages among Hattusha texts, and Cuneiform Luvian was recognized as closely related to Hittite by Hrozný (1920: 35–39 & 55) and Forrer (1922: 215–223, correcting 1919: 1035). Forrer (1922: 241–247) tentatively added Palaic as also related. The affiliation of the language of the “Hittite hieroglyphs” was established by the early 1930s: see Forrer 1932: 59 and passim, Meriggi 1932: 10 and 42–57, and Hrozný 1933: 77–XX). Lycian and Lydian were shown to be Indo-European with special affinity with Hittite-Luvian-Palaic by Meriggi (1936a, 1936b), though this was not universally acknowledged. The concept of an “Anatolian” subgroup of Indo-European was thus existent before the Second World War, even if that label would not become standard for many decades. However, the full impact of the “minor” Anatolian languages on the history of Hittite and its relationship to the rest of Indo-European was long delayed. Handbooks on the historical grammar of Hittite published from the 1930s to the 1970s largely explicated Hittite directly from some model of Proto-Indo- European, treating the other languages very selectively or in appendices: see e.g. Sturtevant 1933, Sturtevant-Hahn 1951, Kronasser 1956 and 1966, and Oettinger 1979. Hittite still played an outsized role in the more comprehensive treatment of 2 Kammenhuber 1969. -

The Writing Revolution

9781405154062_1_pre.qxd 8/8/08 4:42 PM Page iii The Writing Revolution Cuneiform to the Internet Amalia E. Gnanadesikan A John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., Publication 9781405154062_1_pre.qxd 8/8/08 4:42 PM Page iv This edition first published 2009 © 2009 Amalia E. Gnanadesikan Blackwell Publishing was acquired by John Wiley & Sons in February 2007. Blackwell’s publishing program has been merged with Wiley’s global Scientific, Technical, and Medical business to form Wiley-Blackwell. Registered Office John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, United Kingdom Editorial Offices 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services, and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com/wiley-blackwell. The right of Amalia E. Gnanadesikan to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher. Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books. Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. -

Introduction

Introduction 1 . The present volume in the context of preceding experiences The first volume of the series LautSchriftSprache – ScriptandSound deals with some of the topics presented during the third international LSS conference in Verona (www.linguistic- slab.org/lss_3), as well as with some new ones. In chronological terms, the papers in the present volume refer to writing systems ranging from the cuneiform systems of the II. millen- nium B.C. to present-day alphabets; in relation to the geographical coordinates, they extend from the Middle East, and the Caucasus to continental Europe and the Mediterranean Area . The first LSS conference in Zurich 2008 gave an overall introduction to the broad field of historical graphemics, summing up the results of many research programs on runes and other writing system of the Middle Ages. The second one, in Munich in 2010, focused on the (dis-)ambiguity of the grapheme and the depiction of sounds by characters in terms of a ‘perfect fit’, giving an overview on different writing systems. The third conference followed these traces in attempting to broaden the range of phenomena studied . A detailed list of topics is offered below. 1 . Metalanguage . A scrutiny of metalinguistic thinking based on the history of the underlying concepts (e g. grapheme, graph, character, letter, syllabogramm, phonogramm, logogramm, graphemics, graphetics, allograph, glyph, alloglyph etc .) and on their critical analysis . 2. Functions. The concept of a ‘perfect fit’ is further studied especially in the light of stud- ies on literacy, semiotics and the theory of communication. We tried to raise the following questions: How far can we speak of (im)perfection, once we consider the roles of senders, recipients and goals in their own context and in the context of our research? Can writing systems only be classified in relation to a glotto-phonemic – grapho-phonemic ‘perfect fit’ or also in relation to the concept of ‘key’ in communication? How relevant are considerations of specialized vs. -

A Study in the Syntax of the Luwian Language

federico giusfredi A Study giusfredi in the Syntax of the Luwian giusfredi A Study in the Syntax of the Luwian Language Language THeth he Ancient Anatolian corpora represent the ear- 30 liest documented examples of the Indo-European languages. In this book, an analysis of the syntactic of A Study structure of the Luwian phrases, clauses, and sen- the tences is attempted, basing on a phrase-structural approach that entails a mild application of the the- Luwian in oretical framework of generative grammar. While the obvious limits exist as regards the use of theory-driv- Language en models to the study and description of ancient Syntax corpus-languages, this book aims at demonstrating and illustrating the main configurational features of the Luwian syntax. Universitätsverlag winter Heidelberg texte der hethiter Philologische und historische Studien zur Altanatolistik Begründet von Annelies Kammenhuber † Weitergeführt von Gernot Wilhelm Susanne Heinhold-Krahmer Neu herausgegeben von Paola Cotticelli-Kurras Wissenschaftlicher Beirat Stefano De Martino (Turin) Mauro Giorgeri (Pavia) Federico Giusfredi (Verona) Susanne Heinhold-Krahmer (Feldkirchen) Theo van den Hout (Chicago) Annick Payne (Bern) Alfredo Rizza (Verona) Heft 30 federico giusfredi A Study in the Syntax of the Luwian Language Universitätsverlag winter Heidelberg This book contains the results of the project sluw, that has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie Grant Agreement no. 655954 Universitätsverlag Winter GmbH Dossenheimer Landstraße 13 d-69121 Heidelberg www.winter-verlag.de text: © Federico Giusfredi 2020 gesamtherstellung: Universitätsverlag Winter GmbH, Heidelberg isbn (Print): 978-3-8253-4725-3 isbn (oa): 978-3-8253-7953-7 doi: https://doi.org/10.33675/2020-82537953 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution – Non Commercial – No Derivatives 4.0 International License. -

Anatolian Hieroglyphs

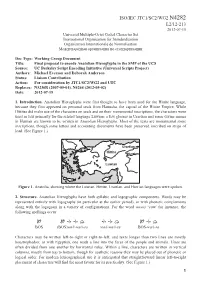

ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 N4282 L2/12-213 2012-07-15 Universal Multiple-Octet Coded Character Set International Organization for Standardization Organisation Internationale de Normalisation Международная организация по стандартизации Doc Type: Working Group Document Title: Final proposal to encode Anatolian Hieroglyphs in the SMP of the UCS Source: UC Berkeley Script Encoding Initiative (Universal Scripts Project) Authors: Michael Everson and Deborah Anderson Status: Liaison Contribution Action: For consideration by JTC1/SC2/WG2 and UTC Replaces: N3236R (2007-05-01), N4264 (2012-05-02) Date: 2012-07-15 1. Introduction. Anatolian Hieroglyphs were first thought to have been used for the Hittite language, because they first appeared on personal seals from Hattusha, the capital of the Hittite Empire. While Hittites did make use of the characters on seals and on their monumental inscriptions, the characters were used as text primarily for the related language Luwian; a few glosses in Urartian and some divine names in Hurrian are known to be written in Anatolian Hieroglyphs. Most of the texts are monumental stone inscriptions, though some letters and accounting documents have been preserved inscribed on strips of lead. (See Figure 1.) Urartian ’ Hittite Hurrian Luwian Figure 1. Anatolia, showing where the Luwian, Hittite, Urartian, and Hurrian languages were spoken. 2. Structure. Anatolian Hieroglyphs have both syllabic and logographic components. Words may be represented entirely with logographs (in particular at the earlier period), or with phonetic complements along with the logogram in a variety of configurations. For the word wawis ‘cow’ for instance, the following spellings occur: BOS (BOS)wa/i-wa/i-sa wa/i-wa/i-sa BOS-wa/i-sa Characters may be written left-to-right or right-to-left, and texts longer than two lines are mostly boustrophedon; as with Egyptian, one reads a line into the faces of the people and animals. -

1. the Appearance of Cuneiform

THE SPREAD OF ‘HEAVENLY WRITING’ Marina ZORMAN University of Ljubljana [email protected] Abstract Cuneiform is the name of various writing systems in use throughout the Middle East from the end of the fourth millennium BCE until the late first century CE. The wedge-shaped writing was used to write ten to fifteen languages from various language families: Sumerian, Elamite, Eblaite, Old Assyrian, Old Babylonian and other Akkadian dialects, Proto-Hattic, Hittite, Luwian, Palaic, Hurrian, Urartian, Ugaritic, Old Persian etc. Over the centuries it evolved from a pictographic to a syllabographic writing system and eventually became an alphabetic script, but most languages used a 'mixed orthography' which combined ideographic and phonetic elements, and required a rebus principle of reading. Keywords: cuneiform; writing; history of writing; writing in Mesopotamia Povzetek Izraz klinopis se uporablja za poimenovanje različnih načinov pisanja, ki so se uporabljali v Mezopotamiji in na Bližnjem vzhodu od konca četrtega tisočletja pr. n. š. do druge polovice prvega stoletja n. š. Pisava, katere osnovni element po obliki spominja na klin, je služila za zapisovanje do petnajst jezikov iz različnih jezikovnih družin: sumerščine, elamščine, eblanščine, stare asirščine, stare babilonščine in drugih akadijskih dialektov, protohatijščine, hetitščine, luvijščine, palajščine, huritščine, urartijščine, ugaritščine, stare perzijščine itd. V teku stoletij se je iz podobopisa razvila v zlogovno in nazadnje v glasovno pisavo, vendar jo je večina jezikov uporabljala tako, da so se v njej izmenoma pojavljali ideografski in fonetičnimi elementi. Branje take pisave je bilo podobno reševanju rebusov. Keywords: klinopis; pisava; vrste pisav; razvoj pisave; pisava v Mezopotamiji 1. The appearance of cuneiform Cuneiform – or 'Heavenly Writing' as this writing system is also called – represents one of the earliest and most influential writing systems of the world.