Hava Nagila1 a Personal Reflection on the Reception of Jewish Music in Germany

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Resource Guide to Literature, Poetry, Art, Music & Videos by Holocaust

Bearing Witness BEARING WITNESS A Resource Guide to Literature, Poetry, Art, Music, and Videos by Holocaust Victims and Survivors PHILIP ROSEN and NINA APFELBAUM Greenwood Press Westport, Connecticut ● London Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Rosen, Philip. Bearing witness : a resource guide to literature, poetry, art, music, and videos by Holocaust victims and survivors / Philip Rosen and Nina Apfelbaum. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references (p.) and index. ISBN 0–313–31076–9 (alk. paper) 1. Holocaust, Jewish (1939–1945)—Personal narratives—Bio-bibliography. 2. Holocaust, Jewish (1939–1945), in literature—Bio-bibliography. 3. Holocaust, Jewish (1939–1945), in art—Catalogs. 4. Holocaust, Jewish (1939–1945)—Songs and music—Bibliography—Catalogs. 5. Holocaust,Jewish (1939–1945)—Video catalogs. I. Apfelbaum, Nina. II. Title. Z6374.H6 R67 2002 [D804.3] 016.94053’18—dc21 00–069153 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available. Copyright ᭧ 2002 by Philip Rosen and Nina Apfelbaum All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 00–069153 ISBN: 0–313–31076–9 First published in 2002 Greenwood Press, 88 Post Road West, Westport, CT 06881 An imprint of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. www.greenwood.com Printed in the United States of America TM The paper used in this book complies with the Permanent Paper Standard issued by the National Information Standards Organization (Z39.48–1984). 10987654321 Contents Preface vii Historical Background of the Holocaust xi 1 Memoirs, Diaries, and Fiction of the Holocaust 1 2 Poetry of the Holocaust 105 3 Art of the Holocaust 121 4 Music of the Holocaust 165 5 Videos of the Holocaust Experience 183 Index 197 Preface The writers, artists, and musicians whose works are profiled in this re- source guide were selected on the basis of a number of criteria. -

POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews Warsaw 2013 Museum of the City of New York New York 2014 the Contemporary Jewish Muse

POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews Warsaw 2013 Museum of the City of New York New York 2014 The Contemporary Jewish Museum San Francisco 2015 Sokołów, video; 2 minutes Courtesy of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, New York Letters to Afar is made possible with generous support from the following sponsors: POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews Polish Ministry of Culture and National Heritage Museum of the City of New York Kronhill Pletka Foundation New York City Department of Cultural Affairs Righteous Persons Foundation Seedlings Foundation Mr. Sigmund Rolat The Contemporary Jewish Museum Patron Sponsorship: Major Sponsorship: Anonymous Donor David Berg Foundation Gaia Fund Siesel Maibach Righteous Persons Foundation Taube Foundation for Jewish Life & Culture Anita and Ronald Wornick Major support for The Contemporary Jewish Museum’s exhibitions and Jewish Peoplehood Programs comes from the Koret Foundation. POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews, Warsaw 05.18.2013 - 09.30.2013 Museum of the City of New York 10.22.2014 - 03.22.2015 The Contemporary Jewish Museum, San Francisco 02.26.2015 - 05.24.2015 Video installation by Péter Forgács with music by The Klezmatics, commissioned by the Museum of the History of Polish Jews and the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research. The footage used comes from the collections of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research in New York, the National Film Archive in Warsaw, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, Beit Hatfutsot in Tel Aviv and the Steven Spielberg Jewish Film Archive in Jerusalem. 4 Péter Forgács / The Klezmatics Kolbuszowa, video; 23 minutes Courtesy of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, New York 6 7 Péter Forgács / The Klezmatics beginning of the journey Andrzej Cudak The Museum of the History of Polish Jews invites you Acting Director on a journey to the Second Polish-Jewish Republic. -

“Friends” Co-Creator Marta Kauffman to Produce “Hava Nagila” Documentary

Contact: Roberta Grossman 323.424.4210 [email protected] www.katahdin.org “FRIENDS” CO-CREATOR MARTA KAUFFMAN TO PRODUCE “HAVA NAGILA” DOCUMENTARY EMMY AWARD-WINNING PRODUCER RETEAMS WITH “BLESSED IS THE MATCH” FILMMAKERS TO EXPLORE THE HISTORY, MYSTERY AND MEANING OF THE ICONIC JEWISH SONG Hollywood, CA (January 27, 2011) – Emmy Award-winning producer Marta Kauffman is reteaming with her partners on the documentary Blessed Is the Match to bring the story of the iconic song “Hava Nagila” to the screen. Funny, deep and unexpected, Hava Nagila: What Is It? will celebrate 100 years of Jewish history and culture through the journey of a song, and reveal the power of music to bridge cultural divides and bring us together as human beings. “We are thrilled to be working with Marta again,” says director Roberta Grossman, whose film Blessed Is the Match, about Holocaust heroine Hannah Senesh, was shortlisted for an Academy Award, won the audience award at 13 film festivals, was broadcast on PBS in 2010, and nominated for a Primetime Emmy. “Marta is someone who elevates every project she touches, and her experience and guidance will only make the film better.” Kauffman was the co-creator and executive producer of the hit TV series Friends. Prior to her work on Friends, Kauffman co-created and co-executive produced the critically acclaimed series Dream On. She co-created the series The Powers That Be, for Norman Lear, and co-created and served as executive producer on the comedy series Family Album and Veronica’s Closet. Kauffman executive produced Blessed Is the Match, working closely with Grossman, producer Lisa Thomas and writer Sophie Sartain. -

A Concert Review by Christof Graf

Leonard Cohen`s Tower Of Song: A Grand Gala Of Excellence Without Compromise by Christof Graf A Memorial Tribute To Leonard Cohen Bell Centre, Montreal/ Canada, 6th November 2017 A concert review by Christof Graf Photos by: Christof Graf “The Leonard Cohen Memorial Tribute ‘began in a grand fashion,” wrote the MONTREAL GAZETTE. “One Year After His Death, the Legendary Singer-Songwriter is Remembered, Spectacularly, in Montral,” headlined the US-Edition of NEWSWEEK. The media spoke of a “Star-studded Montreal memorial concert which celebrated life and work of Leonard Cohen.” –“Cohen fans sing, shout Halleluja in tribute to poet, songwriter Leonard,” was the title chosen by THE STAR. The NATIONAL POST said: “Sting and other stars shine in fast-paced, touching Leonard Cohen tribute in Montreal.” Everyone present shared this opinion. It was a moving and fascinating event of the highest quality. The first visitors had already begun their pilgrimage to the Hockey Arena of the Bell Centre at noon. The organizers reported around 20.000 visitors in the evening. Some media outlets estimated 16.000, others 22.000. Many visitors came dressed in dark suits and fedora hats, an homage to Cohen’s “work attire.” Cohen last sported his signature wardrobe during his over three hour long concerts from 2008 to 2013. How many visitors were really there was irrelevant; the Bell Centre was filled to the rim. The “Tower Of Song- A Memorial Tribute To Leonard Cohen” was sold out. Expectations were high as fans of the Canadian Singer/Songwriter pilgrimmed from all over the world to Montreal to pay tribute to their deceased idol. -

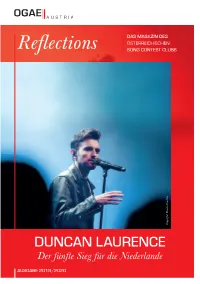

Reflections 3 Reflections

3 Refl ections DAS MAGAZIN DES ÖSTERREICHISCHEN Refl ections SONG CONTEST CLUBS AUSGABE 2019/2020 AUSGABE | TAUSEND FENSTER Der tschechische Sänger Karel Gott („Und samkeit in der großen Stadt beim Eurovision diese Biene, die ich meine, die heißt Maja …“) Song Contest 1968 in der Royal Albert Hall wurde vor allem durch seine vom böhmischen mit nur 2 Punkten den bescheidenen drei- SONG CONTEST CLUBS Timbre gekennzeichneten, deutschsprachigen zehnten Platz, fi ndet aber bis heute großen Schlager in den 1970er und 1980er Jahren zum Anklang innerhalb der ESC-Fangemeinde. Liebling der Freunde eingängiger U-Musik. Neben der deutschen Version, nahm Karel Copyright: Martin Krachler Ganz zu Beginn seiner Karriere wurde er Gott noch eine tschechische Version und zwei ÖSTERREICHISCHEN vom Österreichischen Rundfunk eingela- englische Versionen auf. den, die Alpenrepublik mit der Udo Jürgens- Hier seht ihr die spanische Ausgabe von „Tau- DUNCAN LAURENCE Komposition „Tausend Fenster“ zu vertreten. send Fenster“, das dort auf Deutsch veröff ent- Zwar erreichte der Schlager über die Ein- licht wurde. MAGAZINDAS DES Der fünfte Sieg für die Niederlande DIE LETZTE SEITE | ections Refl AUSGABE 2019/2020 2 Refl ections 4 Refl ections 99 Refl ections 6 Refl ections IMPRESSUM MARKUS TRITREMMEL MICHAEL STANGL Clubleitung, Generalversammlung, Organisation Clubtreff en, Newsletter, Vorstandssitzung, Newsletter, Tickets Eurovision Song Contest Inlandskorrespondenz, Audioarchiv [email protected] Fichtestraße 77/18 | 8020 Graz MARTIN HUBER [email protected] -

2006 Abstracts

Works in Progress Group in Modern Jewish Studies Session Many of us in the field of modern Jewish studies have felt the need for an active working group interested in discussing our various projects, papers, and books, particularly as we develop into more mature scholars. Even more, we want to engage other committed scholars and respond to their new projects, concerns, and methodological approaches to the study of modern Jews and Judaism, broadly construed in terms of period and place. To this end, since 2001, we have convened a “Works in Progress Group in Modern Jewish Studies” that meets yearly in connection with the Association for Jewish Studies Annual Conference on the Saturday night preceding the conference. The purpose of this group is to gather interested scholars together and review works in progress authored by members of the group and distributed and read prior to the AJS meeting. 2006 will be the sixth year of a formal meeting within which we have exchanged ideas and shared our work with peers in a casual, constructive environment. This Works in Progress Group is open to all scholars working in any discipline within the field of modern Jewish studies. We are a diverse group of scholars committed to engaging others and their works in order to further our own projects, those of our colleagues, and the critical growth of modern Jewish studies. Papers will be distributed in November. To participate in the Works in Progress Group, please contact: Todd Hasak-Lowy, email: [email protected] or Adam Shear, email: [email protected] Co-Chairs: Todd S. -

What Makes Klezmer So Special? Geraldine Auerbach Ponders the World Wide Popularity of Klezmer Written November 2009 for JMI Newsletter No 17

What Makes Klezmer so Special? Geraldine Auerbach ponders the world wide popularity of klezmer Written November 2009 for JMI Newsletter no 17 Picture this: Camden Town’s Jazz Café on 12 August 2009 with queues round the block including Lords of the realm, hippies, skull-capped portly gents, and trendy young men and women. What brought them all together? They were all coming to a concert of music called Klezmer! So what exactly is klezmer, and how, in the twenty-first century, does it still manage to resonate with and thrill the young and the old, the hip and the nostalgic, alike? In the 18th and 19th centuries, in the Jewish towns and villages of Eastern Europe the Yiddish term 'klezmer' referred to Jewish musicians themselves. They belonged to professional guilds and competed for work at weddings and parties for the Jewish community – as well as the local gentry. Their repertory included specific Jewish tunes as well as local hit songs played on the instruments popular in the locality. Performance was influenced by the ornamented vocal style of the synagogue cantor. When life became intolerable for Jews in Eastern Europe in the late nineteenth century, and opportunity came for moving to newer worlds – musicians brought this music to the west, adapting all the while to immigrant tastes and the new recording scene. During the mid-twentieth century, this type of music fell from favour as the sons and daughters of Jewish immigrants turned to American and British popular styles. But just a few decades later, klezmer was back! A new generation of American musicians reclaimed the music of their predecessors. -

Rezension Im Erweiterten Forschungskontext: ESC 2016

Repositorium für die Medienwissenschaft Christoph Oliver Mayer Rezension im erweiterten Forschungskontext: ESC 2016 https://doi.org/10.17192/ep2016.1.4446 Veröffentlichungsversion / published version Rezension / review Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Mayer, Christoph Oliver: Rezension im erweiterten Forschungskontext: ESC. In: MEDIENwissenschaft: Rezensionen | Reviews, Jg. 33 (2016), Nr. 1. DOI: https://doi.org/10.17192/ep2016.1.4446. Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Creative Commons - This document is made available under a creative commons - Namensnennung 3.0/ Lizenz zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Attribution 3.0/ License. For more information see: Auskünfte zu dieser Lizenz finden Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/ https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/ Hörfunk und Fernsehen 99 Rezension im erweiterten Forschungskontext: ESC Christine Ehardt, Georg Vogt, Florian Wagner (Hg.): Eurovision Song Contest: Eine kleine Geschichte zwischen Körper, Geschlecht und Nation Wien: Zaglossus 2015, 344 S., ISBN 9783902902320, EUR 19,95 Der Sieg von Conchita Wurst beim Triebel 2011; Goldstein/Taylor 2013) Eurovision Song Contest (ESC) 2014 sowie von einzelnen Wissenschaft- und die sich daran anschließenden ler_innen unterschiedlicher Disziplinen europaweiten Diskussionen um Tole- (z.B. Sieg 2013; Mayer 2015) angesto- ranz und Gleichberechtigung haben ßen wurden. eine ganze Palette von Publikationen Gemeinsam ist all den neueren über den bedeutendsten Populärmusik- Ansätzen ein gesteigertes Interesse für Wettbewerb hervorgerufen (z.B. Wol- Körperinszenierungen, Geschlech- ther/Lackner 2014; Lackner/Rau 2015; terrollen und Nationsbildung, denen Vogel et al. 2015; Kennedy O’Connor sich auch der als „kleine Geschichte“ 2015; Vignoles/O’Brien 2015). Nur untertitelte Sammelband der Wie- wenige wissenschaftliche Monografien ner Medienwissenschaftler_innen (z.B. -

Esther Ofarim Esther Ofarim Mp3, Flac, Wma

Esther Ofarim Esther Ofarim mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Pop / Folk, World, & Country Album: Esther Ofarim Country: Germany Released: 1972 MP3 version RAR size: 1643 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1493 mb WMA version RAR size: 1945 mb Rating: 4.4 Votes: 481 Other Formats: MP4 VQF MP3 AU AAC APE WAV Tracklist Hide Credits Song Of The French Partisan A1 3:35 Written-By – Zaret* Suzanne A2 5:13 Written-By – Cohen* You're Always Looking For The Rainbow A3 3:54 Written-By – Johnston* El Condor Pasa A4 4:25 Written-By – Robles*, Milchberg* Jerusalem A5 3:40 Written-By – Cornelius* Boy From The Country B1 4:28 Written-By – Murphey*, Castleman* Gnostic Serenade B2 4:17 Written-By – Hawkins* Morning Has Broken B3 2:22 Arranged By – Stevens*Lyrics By – Farjeon* Hey, That's No Way To Say Goodbye B4 3:37 Written-By – Cohen* Waking Up B5 3:49 Written-By – Murphey* Companies, etc. Record Company – EMI Electrola Credits Engineer – Bob Potter Producer – Bob Johnston Vocals – Esther Ofarim Notes Recorded at Command Studios, London and Mixedin Nashville Tennessee Probably a mid-70s pressing Comes in a matt-laminated gatefold sleeve Blue EMI Columbia labels "ST 33" in two ovals instead of two circles Barcode and Other Identifiers Rights Society: GEMA Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Esther 1C 062-05 178 Esther Ofarim (LP) Columbia 1C 062-05 178 Germany 1972 Ofarim Esther BB 29564 Esther Ofarim (LP) BASF Systems BB 29564 US 1973 Ofarim Esther Esther Ofarim (LP, SCXA 9253 Portrait SCXA 9253 Israel Unknown Ofarim Album) SCXA 9253, IE Esther Esther Ofarim (LP, Columbia, SCXA 9253, IE UK 1972 064 o 05178 Ofarim Album, Gat) Columbia 064 o 05178 Esther Esther Ofarim (LP, 1C 062-05 294 EMI Ltd. -

Communist Nationalisms, Internationalisms, and Cosmopolitanisms

Edinburgh Research Explorer Communist nationalisms, internationalisms, and cosmopolitanisms Citation for published version: Kelly, E 2018, Communist nationalisms, internationalisms, and cosmopolitanisms: The case of the German Democratic Republic. in E Kelly, M Mantere & DB Scott (eds), Confronting the National in the Musical Past. 1st edn, Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315268279 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.4324/9781315268279 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: Confronting the National in the Musical Past General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 01. Oct. 2021 Preprint. Published in Confronting the National in the Musical Past, ed. Elaine Kelly, Markus Mantere, and Derek B. Scott (London & New York: Routledge, 2018), pp. 78- 90. Chapter 5 Communist Nationalisms, Internationalisms, and Cosmopolitanisms: The Case of the German Democratic Republic Elaine Kelly One of the difficulties associated with attempts to challenge the hegemony of the nation in music historiography is the extent to which constructs of nation, national identity, and national politics have actually shaped the production and reception of western art music. -

Country Christmas ...2 Rhythm

1 Ho li day se asons and va ca tions Fei er tag und Be triebs fe rien BEAR FAMILY will be on Christmas ho li days from Vom 23. De zem ber bis zum 10. Ja nuar macht De cem ber 23rd to Ja nuary 10th. During that peri od BEAR FAMILY Weihnach tsfe rien. Bestel len Sie in die ser plea se send written orders only. The staff will be back Zeit bitte nur schriftlich. Ab dem 10. Janu ar 2005 sind ser ving you du ring our re gu lar bu si ness hours on Mon- wir wie der für Sie da. day 10th, 2004. We would like to thank all our custo - Bei die ser Ge le gen heit be dan ken wir uns für die gute mers for their co-opera ti on in 2004. It has been a Zu sam men ar beit im ver gan ge nen Jahr. plea su re wor king with you. BEAR FAMILY is wis hing you a Wir wünschen Ihnen ein fro hes Weih nachts- Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year. fest und ein glüc kliches neu es Jahr. COUNTRY CHRISTMAS ..........2 BEAT, 60s/70s ..................86 COUNTRY .........................8 SURF .............................92 AMERICANA/ROOTS/ALT. .............25 REVIVAL/NEO ROCKABILLY ............93 OUTLAWS/SINGER-SONGWRITER .......25 PSYCHOBILLY ......................97 WESTERN..........................31 BRITISH R&R ........................98 WESTERN SWING....................32 SKIFFLE ...........................100 TRUCKS & TRAINS ...................32 INSTRUMENTAL R&R/BEAT .............100 C&W SOUNDTRACKS.................33 C&W SPECIAL COLLECTIONS...........33 POP.............................102 COUNTRY CANADA..................33 POP INSTRUMENTAL .................108 COUNTRY -

Instrumental

Instrumental Intermediate Winds (Christian Dawid) Intermediate| Tuesday-Friday |AM1 - 9:30-10:45 In this class, we’ll work on klezmer ornamentation: how to apply it, phrasing, feel, variation, and more. One topic a day. Tips and tricks generously delivered. Open to all melody wind instrumentalists who want to work at a moderate pace, or are new to klezmer. Depending on group size, we might have time for individual coaching as well. PDFs of workshop material (according to your instrument's tuning: Bb, Concert Eb) will be provided to download before the class. Looking forward to meeting you! Christian Dawid is presented thanks to the generous support of the Consulate General of the Federal Republic of Germany, Montreal. Register for Intermediate Winds Advanced Winds (Zilien Biret) Advanced| Tuesday-Friday |AM1 - 9:30-10:45 Dave Tarras himself once said that he never played the same melodic phrase twice, always ornamenting or articulating in a different way. Working with the repertoire of Naftule Brandwein and Titunschneider, we will repeat phrases by ear and learn how to give a strong klezmer character to a repetitive melody. This is a master-class, so please prepare a tune you would like to share with us. I will help you with little tips to piece together the magic of klezmer. Register for Advanced Winds Intermediate Strings (Amy Zakar) Intermediate| Tuesday-Friday |AM1 - 9:30-10:45 For bowed strings: violin, viola, cello, bass, et. al. Play repertoire and learn string-specific klezmer style to start out your morning with good cheer! This class will be a good fit for you if you are past the beginning technical stage of learning your instrument, but are not yet performing on a regular basis or playing at an orchestral level.