Conservative Constructionist: the Early Influence of Billy Graham in Britain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cultural Role of Christianity in England, 1918-1931: an Anglican Perspective on State Education

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 1995 The Cultural Role of Christianity in England, 1918-1931: An Anglican Perspective on State Education George Sochan Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Sochan, George, "The Cultural Role of Christianity in England, 1918-1931: An Anglican Perspective on State Education" (1995). Dissertations. 3521. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/3521 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1995 George Sochan LOYOLA UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO THE CULTURAL ROLE OF CHRISTIANITY IN ENGLAND, 1918-1931: AN ANGLICAN PERSPECTIVE ON STATE EDUCATION A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BY GEORGE SOCHAN CHICAGO, ILLINOIS JANUARY, 1995 Copyright by George Sochan Sochan, 1995 All rights reserved ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter I. INTRODUCTION • ••.••••••••••.•••••••..•••..•••.••.•• 1 II. THE CALL FOR REFORM AND THE ANGLICAN RESPONSE ••.• 8 III. THE FISHER ACT •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 35 IV. NO AGREEMENT: THE FAILURE OF THE AMENDING BILL •. 62 v. THE EDUCATIONAL LULL, 1924-1926 •••••••••••••••• 105 VI. THE HADOW REPORT ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 135 VII. THREE FAILED BILLS, THEN THE DEPRESSION •••••••• 168 VIII. CONCLUSION ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 218 BIBLIOGRAPHY •••••••••.••••••••••.••.•••••••••••••••••.• 228 VITA ...........................................•....... 231 iii CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION Since World War II, beginning especially in the 1960s, considerable work has been done on the history of the school system in England. -

BILLY GRAHAM LIBRARY BILLY Children, the Ladies Tea and Tour in April, to Them Through This Wonderful Facility

BILLY GRAHAM EVANGELISTIC ASSOCIATION A TIME for DECISION 2016 ANNUAL REPORT “Faith comes by hearing.” —Romans 10:17 2016 A TIME for DECISION BILLY GRAHAM EVANGELISTIC ASSOCIATION MINISTRY REPORT “There is one God and ATLANTA, GA.: Franklin Graham one Mediator between speaks to nearly DEAR FRIEND, God and men, the Man 7,000 at the Decision America The Billy Graham Evangelistic Association Christ Jesus, who gave Tour’s sixth stop. (BGEA) experienced a year like no other in 2016. I thank God for the Himself a ransom for all.” unprecedented opportunity to go to all 50 —1 Timothy 2:5–6 states, stand on the capitol steps, share the Good News of Jesus Christ, and call thousands upon thousands of people to prayer during the Decision America Tour. 1,800,000 It was amazing. Never did we dream there would be such a harvest of souls at these rallies—and we give God all the glory. Our nation’s need for prayer didn’t end with the election, a new administration in Washington, or a new year. America still needs the message of “the gospel of Christ, for it is the power of God to salvation for everyone who believes” (Romans 1:16). The one sure path to national restoration is through repentance, and only the Good News of God’s Son can humble hearts and change them—across our nation or anywhere in the world. During 2016, more than 1.8 million people across the globe told us they made a life-changing decision for Christ as a result of God working through BGEA’s ministries. -

FUNDRAISING REPORT 17 Mike And

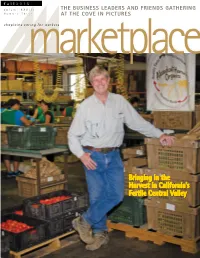

fall2015 Volume XXVIII THE BUSINESS LEADERS AND FRIENDS GATHERING Number Three AT THE COVE IN PICTURES chaplains caringmarketplace for workers Bringing in the Harvest in California’s Fertile Central Valley fall2015 A publication of Marketplace Ministries – Marketplace Chaplains USA contents Volume XXVIII marketplace Number Three chaplains caring for workers Marketplace is the magazine for Marketplace Ministries Inc., a non-profit, nondenominational Christian organization whose goal is to care for people in the workplace. Marketplace Ministries is able to operate because of the tax- deductible contributions made by people like you. In addition to letting you know how the ministry is progressing, Marketplace Ministries wants to thank you for enabling us to continue to care for people in the marketplace. Governing Board Foundation Board William R. Thomas, III Gil A. Stricklin Chairman Chairman, CEO & President Ed Bonneau Ed Bonneau Doug Fagerstrom Dan Farell Casey Gurganus Kyle Hearon Craig Hodges Mark Lovvorn 6 8 Neal Jeffrey, Jr. Calvin McKaig, MD Calvin McKaig, MD Ray Pace Andy Nace O.R. “Butch” Smith Phil Swatzell ——— Advisory Board ——— Tom Freet Ben March Chairman Nelson McKinney Jack Allen Phil McKinzie Pat Beckham Bob Osburn Carl Bolin Ray Pace Ted Raines Os Chrisman Louis Cole Del Rogers, Sr. Bill Crocker Bo Sexton Sam Forester Ann Sneed Gary Golden Ken Stohner, Jr. Ann Stricklin 2 10 Bruce Grantham Jerry Halcomb Charles Tandy, MD Patrick Hamner Greg Terrell Jim Harris James Williamson Jerry Wilson Steve Kerns HOW TO REACH US Bringing in the Harvest Headquarters 972-941-4400 2 Toll-Free 800-775-7657 Fax 972-578-5754 INTERNET ADDRESSES 6 North Carolina Chaplain Tony Wilson Awarded 2015 E-MAIL ADDRESS [email protected] Marketplace Chaplain of the Year [email protected] WEB SITE www.mchapusa.com www.marketplaceministries.com www.seniorlivingchaplains.com Training and Education — The Heartbeat of Marketplace 7 MARKETPLACE CHAPLAINS USA REGION OFFICE INFORMATION Ministries Eastern Region – Atlanta Shane Satterfield – Vice President 4485 Tench Rd. -

TB Vol 25 No 04B December 2008

Volume 25 Issue 4b TORCH BEARER THE 1948 OLYMPIC GAMES, LONDON 999 ELPO. SOCIETY of OLYMPIC C OLLECTORS SOCIETY of OLYMPIC COLLECTORS The representative of F.I.P.O. in Great Britain YOUR COMMITTEE CHAIRMAN Bob Farley, 3 Wain Green, Long Meadow, AND EDITOR : Worcester, WR4 OHP, Great Britain. [email protected] VICE CHAIRMAN : Bob Wilcock, 24 Hamilton Crescent, Brentwood, Essex, CM14 5 ES, Great Britain. [email protected] SECRETARY : Miss Paula Burger, 19 Hanbury Path, Sheerwater, Woking, Surrey, GU21 5RB Great Britain. TREASURER AND David Buxton, 88 Bucknell Road, Bicester, ADVERTISING : Oxon, OX26 2DR, Great Britain. [email protected] AUCTION MANAGER : John Crowther, 3 Hill Drive, Handforth, Wilmslow, Cheshire, SK9 3AP, Great Britain. [email protected] DISTRIBUTION MANAGER, Ken Cook, 31 Thorn Lane, Rainham, Essex, BACK ISSUES and RM13 9SJ, Great Britain. LIBRARIAN : [email protected] PACKET MANAGER Brian Hammond, 6 Lanark Road, Ipswich, IP4 3EH new email to be advised WEB MANAGER Mike Pagnamenos [email protected] P. R. 0. Andy Potter [email protected] BACK ISSUES: At present, most issues of TORCH BEARER are still available to Volume 1, Issue 1, (March 1984), although some are now exhausted. As stocks of each issue run out, they will not be reprinted. It is Society policy to ensure that new members will be able to purchase back issues for a four year period, but we do not guarantee stocks for longer than this. Back issues cost £2.00 each, or £8.00 for a year's issues to Volume 24, and £2.50 per issue, or £10 for a year's issues from Volume 25, including postage by surface mail. -

Homer Rodeheaver: Reverend Trombone Douglas Yeo Historic

Homer Rodeheaver: Reverend Trombone Douglas Yeo Historic Brass Society Journal (peer-reviewed) Volume 27, 2015 The Historic Brass Society Journal (ISSN1045-4616) is published annually by the Historic Brass Society, Inc. 148 W. 23rd Street, #5F New York, NY 10011 USA YEO 1 Homer Rodeheaver: Reverend Trombone Douglas Yeo Introduction Since his death in 1955, Homer Rodeheaver (1880–1955) has slipped into obscurity, an astonishing fact given that he played the trombone for as many as 100 million people in his lifetime. While not nearly so accomplished as the great trombone soloists of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries such as Arthur Pryor, Simone Mantia, and Leo Zimmerman, Rodeheaver’s use of the trombone in Christian evangelistic meetings—par- ticularly during the years (1910–30) when he was song leader for William Ashley “Billy” Sunday—had an impact on American religious and secular culture that continues today. Rodeheaver’s tree of influence includes many other trombone-playing evangelists and song leaders, including Clifford Barrows, song leader for the evangelistic crusades1 of William Franklin “Billy” Graham. While Homer Rodeheaver was one of the most successful publishers of Christian songbooks and hymnals of the modern era—he owned copyrights to many of the most popular gospel2 songs of the first half of the twentieth century—and was the owner of and a recording artist with one of the first record companies devoted primarily to Christian music, the focus of this article is on Rodeheaver as trombonist and trombone icon, his use of the trombone as a tool in leading large congregations in singing, the particular instruments he used, his trombone recordings, and his legacy and influence in inspiring and encouraging others to utilize the trombone as a tool for large-scale Christian evangelism. -

Source : Bibliothèque Du CIO / IOC Library Source : Bibliothèque Du CIO / IOC Library XIV OLYMPIAD

Source : Bibliothèque du CIO / IOC Library Source : Bibliothèque du CIO / IOC Library XIV OLYMPIAD Source : Bibliothèque du CIO / IOC Library THE OFFICIAL REPORT OF THE ORGANISING COMMITTEE FOR THE XIV OLYMPIAD > PUBLISHED BY THE ORGANISING COMMITTEE FOR THE XIV OLYMPIAD • LONDON · 1948 HIS MAJESTY KING GEORGE VI Source : Bibliothèque du CIO / IOC Library COPYRIGHT - 1951 BY THE ORGANISING COMMITTEE FOR THE XIV OLYMPIAD • LONDON • 1948 t HE spirit of the Oljmpic Games, which has tarried here awhile, sets forth once more. Maj it prosper throughout the world, saje in the keeping of all those who have felt its noble impulse in this great Festival of Sport." i i LORD BURGHLEY, Chairman of the Organising Committee, for the scoreboard at the Closing Ceremony, August 14, 1948. Printed by McCorquodale & Co. Ltd., St. Thomas Street, London, S.E.i Source : Bibliothèque du CIO / IOC Library INTRODUCTION By the General Editor, The Kight Hon. The Lord Burghley, K.C.M.G. N the production and presentation of this Official Report, the Organising Committee has endeavoured to satisfy two primary objects : that the matter shall be, as far as I possible, accurate, and that it shall serve not only as a record of the work leading up to the staging of the London Games of 1948, and of the competitions themselves, but also that it may be of assistance to future Organising Committees in their work. The arrangement of the matter has been dictated, apart from the Results sections and those articles dealing with the celebration of the actual Games themselves, by the arrange ment of the work of the departments of the Organising Committee which it was found necessary to create. -

Divining Darwin: Evolving Responses and the Contribution of David Lack1

S & CB (2014), 26, 53–78 0954–4194 R. J. (SAM) BERRY Divining Darwin: Evolving Responses and the Contribution of David Lack1 Christian believers, particularly evangelicals, often react to evolutionary ideas with more heat than light. A significant contribution to clarifying understanding was a book published in 1957, Evolutionary Theory and Christian Belief by the eminent ornithologist David Lack. It was the first attempt to tease out the issues by a scientist of his calibre. Information about this book has recently been published in a biography of Lack. This essay seeks to put Lack’s contribution into the perspective of both past and continuing perceptions of Christianity and evolution. Key words: Darwin, Darwinism, Evolutionary Theory and Christian Belief, David Lack, Dan and Mary Neylan, C.S.Lewis, human nature, imago Dei This paper is about the contribution of David Lack, one of the most dis- tinguished biologists of the twentieth century, to the debates about evolu- tion and Christianity, and his personal journey thereto. His contribution is significant because of the authority he brought to a book he wrote in 1957, which raised these debates to a much more positive and informed level than had previously been the practice. But before we get to Lack and his book, we need to understand something of the background to the understanding of evolution by both scientists and Christians. The reaction of the Christian community to Darwin’s Origin of Species2 ought to be a simple matter of historical record.3 In practice it is regularly muddied. An Editorial in Nature in 2009 claimed, ‘In England the Church reacted badly to Darwin’s theory, going so far as to say that to believe it was to imperil your soul.’4 There may well have been those who maintained this, but they seem to have been few. -

DISPENSATION and ECONOMY in the Law Governing the Church Of

DISPENSATION AND ECONOMY in the law governing the Church of England William Adam Dissertation submitted in part fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of Wales Cardiff Law School 2009 UMI Number: U585252 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U585252 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 CONTENTS SUMMARY............................................................................................................................................................IV ACKNOWLEDGMENTS..................................................................................................................................VI ABBREVIATIONS............................................................................................................................................VII TABLE OF STATUTES AND MEASURES............................................................................................ VIII U K A c t s o f P a r l i a m e n -

Sean Letter February 21.Indd

February 21, 2018 My dear Friends: I’m writing this a couple of hours after the news broke that Billy Graham died at the age of 99. Like many, many of you, I greatly admired him and his ministry. But two other thoughts occur to me this morning as I reflect on his passing into glory. One is this: as you know, I graduated from Bob Jones University. What you may not know is that Billy attended for a semester before going to Florida Bible Institute and then to Wheaton College—he met Cliff Barrows at BJU. Also, after World War II, but before the decisive 1950 Los Angeles crusade that made Graham a national name, Dr. Bob Jones, Sr., the president of his self-titled college, offered Graham the presidency of the school. In the end, Graham would be president of the Northwestern Schools in Minneapolis, Minnesota (which is why the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association headquarters were in that city for so many years). By the time I got to BJU, Graham was practically “public enemy number one.” In fact, the historian George Marsden once quipped that the way to determine if someone was a fundamentalist was to ask them what they thought about Billy Graham. There were a range of reasons for this—some theological, some methodological, some quite personal—but I especially remember being able to purchase for three dollars a packet of information sold in the bookstore that warned of Graham’s theological “liberalism.” Looking back on all of that now, I can see the ways we all too often attack our should-be friends when they are busy doing the very thing we ought to be and are doing—winning others to Jesus. -

Billy Graham: a New Kind of Evangelist

Monday, Oct. 25, 1954 Billy Graham: A New Kind of Evangelist The first one to come forward was a round, sensible-looking housewife with thick glasses. She stood as still and undramatic as if she were waiting to be served at the meat counter. The next was an eleven-year-old boy who kept his head low to hide his tears: a thin girl appeared behind him and put her arm comfortingly on his shoulder. These three were joined by a broad- shouldered young man whose machine-knitted jersey celebrated a leaping swordfish. then by a pretty young Negro woman in her best clothes with a sleeping baby in her arms. Suddenly there were too many to count, standing on the trampled grass in the blaze of lights. Some of them wept quietly, some of them stared at the ground and some looked upward. Above them all stood a tall, blond young man in a double-breasted tan gabardine suit. His handsome, strong-jawed face was drawn and his blue eyes glittered; for a few seconds he gnawed nervously on a thumbnail, and bright sweat covered his high forehead. He was speaking softly, but with an urgency that seemed to tense every muscle of his body: "You can leave here with peace and joy and happiness such as you've never known. You say: 'Well, 'Billy, that's all well and good. I'll think it over and I may come back some night and I'll—' Wait a minute! You can't come to Christ any time you want to. -

Chick Zamick Canadian Who Played For

Chick Zamick Canadian who played for Nottingham Panthers in the postwar heyday of English ice hockey A Canadian who came to Britain after the Second World War, Victor “Chick” Zamick was one of a large number of his countrymen who sustained the fortunes of professional ice hockey in this country for a period of about 15 years after 1945. A Winnipeg man, he played for Nottingham Panthers, a team whose membership consisted very largely of players from his native city. The British Ice Hockey Association had been founded in 1913, giving the sport, which was very much an import from North America, a governing body in the UK. A gold medal in the 1936 Winter Olympics, won by a British team of decidedly Canadian origin, fuelled interest in the game and from the mid‐1930s professional teams were regularly featured in rinks in and around London. In such fabled venues as the Empire Pool, Wembley, Brighton Sports Stadium, the London Empress Hall, Harringay Arena and Streaham Ice Rink, teams drawing their strength from Canadian players made the game a headline affair in prewar England. While the young Canadians who dominated the rosters were not skilled enough to earn a living in North American pro leagues, they were far better than anything Europe had to offer. Hockey might not get them to the National Hockey League but it was a way to skate away from the family farm or local nickel mine. The English National League began as a seven‐team loop, expanded to 11 in its second year of operation. -

THE ECHO THOUGHT 'Ye Shall Know the Truth"—John 8:32

U-N-MF MENU HUNGRY THE ECHO THOUGHT 'Ye Shall Know the Truth"—John 8:32 VOL. XXXIII, NO. 26 TAYLOR UNIVERSITY UPLAND, INDIANA TUESDAY, APRIL 12, 1949 Dr. Torrey Johnson to Speak at Commencement i-W* Beverly Shea Other Speakers In Final To Appear Exercises Also Secured For Lyceum Dr. Torrey Johnson has been selected by the Senior Class for the Beverly Shea, well-known com 1949 Commencement speaker. The exercises will be held Monday poser of "I'd Rather Have Jesus," morning, June 6th, at 9:30 o'clock in the Maytag Gymnasium. Rev. will present a musical lyceum P• B. Smith, Methodist Minister from Hammond Indiana, will deliver Friday, April 22, at 8:00 in Shrei-| the Baccalaureate address on Sunday morning, June 5th. ner Auditorium. It has been traditional that an Gospel music critics acclaim outstanding missionary give the Beverly Shea's baritone voice one address at the evening campus of the outstanding musical attrac service on Baccaluareate Sunday. tions in evangelical circles. He Dr. George D. Strohm, President has been associated with Youth of the St. Paul Bible Institute, has for Christ, Radio Station WMBI, been selected as guest speaker for and many other Christian agencies this occasion. President Strohm, in wide service. At the present father of Ruth Strohm, senior time he is the singing star on the this year at Taylor, served as a Club Aluminum program. missionary in Tibet and also in Bass-baritone, George Beverly the Phillipines. Shea, is the featured soloist on Professor Kenneth H. Wells, ABC's radio network program Dean of Music at the Chicago which has been heard from coast Evangelistic Institute will be the Dr.