Billy Graham: a New Kind of Evangelist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Red-Tie Bill and the Wingless Bird: Tar Heel Baptists and the Evolution

The Daily Advance, which devoted an average of four full-page Red-Tie Bill and the Wingless Bird: columns a day to the spectacle, glowed with the glory of it all. "The Tar Heel Baptists and the evangelist's grip on the city," wrote Herbert Peele, is almost breathtaking .. The revival is the topic of conversation wherever one Evolution Controversy goes. ... The barber in h1~ chair, the salesman behind his counter, the executive at his desk,, the worker ~t ~1s bench, the laborer at his task are one and all thinking Tom Parramore and talking about religion. 0. SAUNDERS, the puckish editor of the Elizabeth City Inde• And what was the inspirational message that Pasquotank County W;pendent, ·was after the revivalists fang and claw before they could was flocking to the tabernacle twice a day, seven days a week, to hear? get their tabernacle up. He predicted that Elizabeth City was going to It was direct, simple, clear, dramatic: the world, Ham assured his have a "red-hot, rip-snorting, hell-raising, sin-busting carnival of evan• audiences, was about to come to an end. The whole temple of man's gelism" that would last for eight weeks or "as Jong as the town stands wordly achievement-all his cities, his industry, his art, his science, his for it." He declared that Evangelist Mordecai Ham's main business government-were at the brink of an utter and complete destruction there was to work on the emotions of the ignorant and then skip town from which there was no earthly or heavenly hope of being spared. -

FBHS-Journal-2010.Pdf

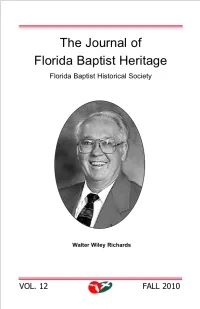

The Journal of Florida Baptist Heritage Florida Baptist Historical Society Published by the FLORIDA BAPTIST HISTORICAL SOCIETY Dr. Jerry M. Windsor, Secretary-Treasurer 5400 College Drive Graceville, Florida 32440 Board of Directors y The State Board of Missions of the Florida t e i c Baptist Convention elects the Board of e o g Directors. S l a a t c i i Rev. Joe Butler r r o t Director of Missions, Black Creek Association e s Mrs. Elaine Coats i H H t Fernandina Beach t s i t Mrs. Clysta De Armas s p i a Port Charlotte t B p Mr. Don Graham a a d Graceville i r B o Dr. Thomas Kinchen l F President, The Baptist College of Florida a e d h t Mrs. Dori Nelson i f r Miami o o l l Dr. Paul Robinson a n F Pensacola r u Rev. Guy Sanders o J Pastor, First Baptist Church, New Port Richey Dr. John Sullivan Executive Director-Treasurer Florida Baptist Convention Cover: Dr. W. Wiley Richards has been preach- ing for 56 years, taught for 36 years and has What We Can Learn about Pastoral Preaching from served 48 interims. Dr. Jerry Oswalt......................................................116 Ed Scott Jerry Windsor-A Passion to Preach, a Burden to Teach Introduction ................................................................4 Preachers ................................................................127 Jerry M. Windsor Joel R. Breidenbaugh The 1885 Preaching of Nathan A. Williams ..............6 Dr. W. Wiley Richards: He Came Teaching...........139 Thomas Field Roger C. Richards A Historical Study of Evangelist Mordecai F. Ham’s 1905-1939 Florida Meetings....................................16 s Jerry Hopkins s t t n Charles Bray Williams n e e t Greek Scholar, Pastor, Preacher...............................28 t n Charlotte Williams Sprawls n o o C The Preaching of Charles Roy Angell C “A Master Collector and Teller of Stories”..............68 Jerry E. -

Identities Bought and Sold, Identity Received As Grace

IDENTITIES BOUGHT AND SOLD, IDENTITY RECEIVED AS GRACE: A THEOLOGICAL CRITICISM OF AND ALTERNATIVE TO CONSUMERIST UNDERSTANDINGS OF THE SELF By James Burton Fulmer Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Vanderbilt University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Religion December, 2006 Nashville, Tennessee Approved: Professor Paul DeHart Professor Douglas Meeks Professor William Franke Professor David Wood Professor Patout Burns ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank all the members of my committee—Professors Paul DeHart, Douglas Meeks, William Franke, David Wood, and Patout Burns—for their support and guidance and for providing me with excellent models of scholarship and mentoring. In particular, I am grateful to Prof. DeHart for his careful, insightful, and challenging feedback throughout the writing process. Without him, I would have produced a dissertation on identity in which my own identity and voice were conspicuously absent. He never tried to control my project but rather always sought to make it more my own. Special thanks also to Prof. Franke for his astute observations and comments and his continual interest in and encouragement of my project. I greatly appreciate the help and support of friends and family. My mom, Arlene Fulmer, was a generous reader and helpful editor. James Sears has been a great friend throughout this process and has always led me to deeper thinking on philosophical and theological matters. Jimmy Barker, David Dault, and Eric Froom provided helpful conversation as well as much-needed breaks. All my colleagues in theology helped with valuable feedback as well. -

BILLY GRAHAM LIBRARY BILLY Children, the Ladies Tea and Tour in April, to Them Through This Wonderful Facility

BILLY GRAHAM EVANGELISTIC ASSOCIATION A TIME for DECISION 2016 ANNUAL REPORT “Faith comes by hearing.” —Romans 10:17 2016 A TIME for DECISION BILLY GRAHAM EVANGELISTIC ASSOCIATION MINISTRY REPORT “There is one God and ATLANTA, GA.: Franklin Graham one Mediator between speaks to nearly DEAR FRIEND, God and men, the Man 7,000 at the Decision America The Billy Graham Evangelistic Association Christ Jesus, who gave Tour’s sixth stop. (BGEA) experienced a year like no other in 2016. I thank God for the Himself a ransom for all.” unprecedented opportunity to go to all 50 —1 Timothy 2:5–6 states, stand on the capitol steps, share the Good News of Jesus Christ, and call thousands upon thousands of people to prayer during the Decision America Tour. 1,800,000 It was amazing. Never did we dream there would be such a harvest of souls at these rallies—and we give God all the glory. Our nation’s need for prayer didn’t end with the election, a new administration in Washington, or a new year. America still needs the message of “the gospel of Christ, for it is the power of God to salvation for everyone who believes” (Romans 1:16). The one sure path to national restoration is through repentance, and only the Good News of God’s Son can humble hearts and change them—across our nation or anywhere in the world. During 2016, more than 1.8 million people across the globe told us they made a life-changing decision for Christ as a result of God working through BGEA’s ministries. -

FUNDRAISING REPORT 17 Mike And

fall2015 Volume XXVIII THE BUSINESS LEADERS AND FRIENDS GATHERING Number Three AT THE COVE IN PICTURES chaplains caringmarketplace for workers Bringing in the Harvest in California’s Fertile Central Valley fall2015 A publication of Marketplace Ministries – Marketplace Chaplains USA contents Volume XXVIII marketplace Number Three chaplains caring for workers Marketplace is the magazine for Marketplace Ministries Inc., a non-profit, nondenominational Christian organization whose goal is to care for people in the workplace. Marketplace Ministries is able to operate because of the tax- deductible contributions made by people like you. In addition to letting you know how the ministry is progressing, Marketplace Ministries wants to thank you for enabling us to continue to care for people in the marketplace. Governing Board Foundation Board William R. Thomas, III Gil A. Stricklin Chairman Chairman, CEO & President Ed Bonneau Ed Bonneau Doug Fagerstrom Dan Farell Casey Gurganus Kyle Hearon Craig Hodges Mark Lovvorn 6 8 Neal Jeffrey, Jr. Calvin McKaig, MD Calvin McKaig, MD Ray Pace Andy Nace O.R. “Butch” Smith Phil Swatzell ——— Advisory Board ——— Tom Freet Ben March Chairman Nelson McKinney Jack Allen Phil McKinzie Pat Beckham Bob Osburn Carl Bolin Ray Pace Ted Raines Os Chrisman Louis Cole Del Rogers, Sr. Bill Crocker Bo Sexton Sam Forester Ann Sneed Gary Golden Ken Stohner, Jr. Ann Stricklin 2 10 Bruce Grantham Jerry Halcomb Charles Tandy, MD Patrick Hamner Greg Terrell Jim Harris James Williamson Jerry Wilson Steve Kerns HOW TO REACH US Bringing in the Harvest Headquarters 972-941-4400 2 Toll-Free 800-775-7657 Fax 972-578-5754 INTERNET ADDRESSES 6 North Carolina Chaplain Tony Wilson Awarded 2015 E-MAIL ADDRESS [email protected] Marketplace Chaplain of the Year [email protected] WEB SITE www.mchapusa.com www.marketplaceministries.com www.seniorlivingchaplains.com Training and Education — The Heartbeat of Marketplace 7 MARKETPLACE CHAPLAINS USA REGION OFFICE INFORMATION Ministries Eastern Region – Atlanta Shane Satterfield – Vice President 4485 Tench Rd. -

Homer Rodeheaver: Reverend Trombone Douglas Yeo Historic

Homer Rodeheaver: Reverend Trombone Douglas Yeo Historic Brass Society Journal (peer-reviewed) Volume 27, 2015 The Historic Brass Society Journal (ISSN1045-4616) is published annually by the Historic Brass Society, Inc. 148 W. 23rd Street, #5F New York, NY 10011 USA YEO 1 Homer Rodeheaver: Reverend Trombone Douglas Yeo Introduction Since his death in 1955, Homer Rodeheaver (1880–1955) has slipped into obscurity, an astonishing fact given that he played the trombone for as many as 100 million people in his lifetime. While not nearly so accomplished as the great trombone soloists of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries such as Arthur Pryor, Simone Mantia, and Leo Zimmerman, Rodeheaver’s use of the trombone in Christian evangelistic meetings—par- ticularly during the years (1910–30) when he was song leader for William Ashley “Billy” Sunday—had an impact on American religious and secular culture that continues today. Rodeheaver’s tree of influence includes many other trombone-playing evangelists and song leaders, including Clifford Barrows, song leader for the evangelistic crusades1 of William Franklin “Billy” Graham. While Homer Rodeheaver was one of the most successful publishers of Christian songbooks and hymnals of the modern era—he owned copyrights to many of the most popular gospel2 songs of the first half of the twentieth century—and was the owner of and a recording artist with one of the first record companies devoted primarily to Christian music, the focus of this article is on Rodeheaver as trombonist and trombone icon, his use of the trombone as a tool in leading large congregations in singing, the particular instruments he used, his trombone recordings, and his legacy and influence in inspiring and encouraging others to utilize the trombone as a tool for large-scale Christian evangelism. -

I, Nebuchadnezzar Rich Nathan July 2 & 3, 2016 Strangers in a Strange Land Daniel 4

I, Nebuchadnezzar Rich Nathan July 2 & 3, 2016 Strangers in a Strange Land Daniel 4 In case you haven’t heard, we are just five months away from electing a new president of the United States. I hope that doesn’t come as a shock to you. But as the presidential campaign heats up, one of the questions that I would love to ask each of the candidates is this: “What do you think the essential problem is with people in America right now? We have lots of problems and lots of issues. Candidate A, you think you deserve to be in the White House for four years and be the most powerful person on earth, tell me why you deserve to run this country by sharing with us your brilliant diagnosis. What is the ultimate problem in our country? Why aren’t we happier than we are? Why are our families breaking down? Why don’t people get along? Why so much division and gridlock?” What is the basic problem in our world? One side will tell you that the main problems in America are all around issues of equality. There’s a growing income gap between rich and poor – in other words, income inequality. There’s a wage and opportunities gap between men and women – gender inequality; a need for criminal justice reform – racial inequality. There’s an educational gap requiring free college for all. From one side of the aisle, the basic problem in America is a lack of equality. The other side will tell you that the main problem in America is that Americans are being kicked around by the rest of the world – by illegal immigrants flooding into our country taking our jobs, by Chinese imports and Chinese currency manipulation undercutting American manufacturers. -

Sean Letter February 21.Indd

February 21, 2018 My dear Friends: I’m writing this a couple of hours after the news broke that Billy Graham died at the age of 99. Like many, many of you, I greatly admired him and his ministry. But two other thoughts occur to me this morning as I reflect on his passing into glory. One is this: as you know, I graduated from Bob Jones University. What you may not know is that Billy attended for a semester before going to Florida Bible Institute and then to Wheaton College—he met Cliff Barrows at BJU. Also, after World War II, but before the decisive 1950 Los Angeles crusade that made Graham a national name, Dr. Bob Jones, Sr., the president of his self-titled college, offered Graham the presidency of the school. In the end, Graham would be president of the Northwestern Schools in Minneapolis, Minnesota (which is why the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association headquarters were in that city for so many years). By the time I got to BJU, Graham was practically “public enemy number one.” In fact, the historian George Marsden once quipped that the way to determine if someone was a fundamentalist was to ask them what they thought about Billy Graham. There were a range of reasons for this—some theological, some methodological, some quite personal—but I especially remember being able to purchase for three dollars a packet of information sold in the bookstore that warned of Graham’s theological “liberalism.” Looking back on all of that now, I can see the ways we all too often attack our should-be friends when they are busy doing the very thing we ought to be and are doing—winning others to Jesus. -

Top 50 Singles Top 50 Albums

CHART KEY <G> GOLD 35000 UNITS <P> PLATINUM 70000 UNITS <D> DIAMOND 500000 UNITS TW THIS WEEK LW LAST WEEK TI TIMES IN HP HIGH POSITION * BULLET TOP 50 SINGLES WEEK COMMENCING 24 MAY, 2021 TOP 50 ALBUMS TW LW TI HP TITLE Artist COMPANY CAT NO. TW LW TI HP TITLE Artist COMPANY CAT NO. 1 1 7 1 BODY Russ Millions & Tion Wayne <G> WUK/WAR GB-AHS-21-00158 * 1 NEW 1 1 BRIDGE OVER TROUBLED DREAMS Delta Goodrem SME 19439859012 * 2 NEW 1 2 GOOD 4 U Olivia Rodrigo INR/UMA 3827222 * 2 NEW 1 2 THE LIVES OF OTHERS You Am I CAR/UMA YAI011CD 3 2 6 2 KISS ME MORE Doja Cat Feat. SZA <G> RCA/SME US-RC1-21-00543 * 3 NEW 1 3 THE OFF-SEASON J. Cole INR/UMA 6116514 4 3 24 1 WITHOUT YOU The Kid Laroi with Miley Cyrus <P>3 SME US-SM1-20-06586 * 4 R/E 2 4 L.W. King Gizzard & The Lizard Wizard FLL/INE FLT-066DA 5 4 24 1 HEAT WAVES Glass Animals <P>3 PDR/UMA 0712076 5 2 9 1 JUSTICE Justin Bieber DEF/UMA B003352102 6 6 14 4 ASTRONAUT IN THE OCEAN Masked Wolf <P> ADA/WAR 075679793102 6 1 3 1 CRY FOREVER Amy Shark WRC/SME LICK041 7 9 32 4 LEVITATING Dua Lipa <P>2 WAR GB-AHT-19-01299 7 3 60 1 FUTURE NOSTALGIA Dua Lipa <G> WAR 9029507610 8 5 8 1 MONTERO (CALL ME BY YOUR NAME) Lil Nas X <P> COL/SME US-SM1-21-00531 * 8 NEW 1 8 DELTA KREAM The Black Keys NONE/WAR 7559791665 9 7 9 1 PEACHES Justin Bieber Feat. -

Mordecai F. Ham, Evangelism and Prohibition Meetings in Texas, 1903-1919

East Texas Historical Journal Volume 44 Issue 2 Article 10 10-2006 No Guarantees: Mordecai F. Ham, Evangelism and Prohibition Meetings in Texas, 1903-1919 Jerry Hopkins Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj Part of the United States History Commons Tell us how this article helped you. Recommended Citation Hopkins, Jerry (2006) "No Guarantees: Mordecai F. Ham, Evangelism and Prohibition Meetings in Texas, 1903-1919," East Texas Historical Journal: Vol. 44 : Iss. 2 , Article 10. Available at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj/vol44/iss2/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History at SFA ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in East Texas Historical Journal by an authorized editor of SFA ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 44 EAST TEXAS HISTORICAl. ASSOCIATION NO GUARANTEE: MORDECAI Ii'. HAM, EVANGELISM AND PROHIBITION MEETINGS IN TEXAS, 1903·1919 By Jerry Hopkins Prohibition, as part of the progressive movement, involved evangelical Christians in Texas and the South. Professional evangelists were particularly drawn to prohibition, viewing it as a moral crusade to save individuals, the church, and society from destruction. To these evangelists drinking liquor was immoral. For Southern evangelicals prohibition had been a persistent preoccu pation. In the South this concern over man's moral depravity, particularly as it was demonstrated in drunkenness, developed into a drive for absolution that found fulfillment in the revivals conducted by such Southern evangelists as Mordecai Fowler Ham. I Mordecai Ham was born in ]877 Allen County, Kentucky, into the fami ly of a Baptist minister. -

Bulgaria Mission Trip March 11, 2018

Volume 64– March 2018 - No. 3 Gulf Coast Baptist Association Monthly Newsletter www.gulfcoastbaptist.org Bulgaria Mission Trip March 11, 2018 Like and follow us on Facebook Please pray for the mission team Gulf Coast Baptist Association departing for Bulgaria on Saturday, March 3rd and returning on Friday, March 16th. Inside This Issue . Mission Team Members The Director Speaks 2 Donald Hintze Sonny Halford Announcements 3 Benjamin Brizendine Calendar 3 Jeanne Newsom In 1999, my first year of full-time ministry, the Billy Graham Crusade was in St. Louis. It was exciting to be a part of the planning and follow up to the crusade and to get to hear Dr. Graham preach each night during the crusade. I took this picture from the floor of the TWA Dome as he was conducting the invitation, and it came to my mind last week when I learned of his death. As many have noted, Billy Graham is probably the most influential person in the 20th Century. He preached the gospel to hundreds of millions around the world and counseled every U.S. president from Harry Truman to Barak Obama. He is known as a man of integrity. It’s safe to say that Billy Graham was probably the best-known person in the world during his day. But do you know the name Mordecai Ham? A fiery evangelist in his own right, he preached revivals across the country, in- cluding Houston, Galveston, Bay City, and the Golden Triangle area. It is estimated that over 300,000 people came to Christ under his preaching. -

Fundamentalist Journal Volume 3, Number 2

Liberty University DigitalCommons@Liberty University 1984 The undF amentalist Journal 2-1984 Fundamentalist Journal Volume 3, Number 2 Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/fun_84 Recommended Citation "Fundamentalist Journal Volume 3, Number 2" (1984). 1984. Paper 5. http://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/fun_84/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the The undF amentalist Journal at DigitalCommons@Liberty University. It has been accepted for inclusion in 1984 by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Liberty University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Canyou trust TheChristian Counseling and EducationalFoundation sponsorsthese one weekcourses of overforty classroomhours specifically to trainthe Christian theBible to pastor,counselor and active lay person to usethe Biblewith confidence, to skillfullyminister to people helpyou withproblems as wellas to examinetheir own lives. counselothers? DR.JAY E. ADAMS,noted author and Dean of the Christian Counselingand Educational Foundation, will lecture throughoutthe week on COUNSELING AND THE BOOK OF Tochange your JA[/ ES DR.LAWRENCE J. CRABB.JR.. Chairman of the Departmentof BiblicalCounseling at Grace Theological ownlife? Seminaryin Winona Lake, lllinois, and respected psychologrst and authorol EffectiveBiblrcal Counseltng and lhe Marrrase BuiHer,will ecture on THEPTACE OF THE BIBLE lN COUNSELING DR.RAY C. STEDMAN,pastor of PeninsulaBible Church rn PaloAlto, California, and author of the popular Body Life, wil lcadthe BIBLE EXPOSITION HOUF DR.JOHN F. BETTLER,Director of theChr stian Counseling andEducational Foundatron. will lecturc on THEBIBLE AND HUN/ANSEXUALITY Role models, gender dentty, homosexualityand marital sexuality are arrrong the top cs coveredin this course. saythese Christian leaders. DR.WAYNE A.