Coversheet for Thesis in Sussex Research Online

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ultimate Test of Leadership Under Stress

MILITARY Ultimate test of leadership under stress The Navy’s Perisher submarine command course is celebrating its centenary Ali Kefford April 15 2017 The Times Lieutenant-Commander Dan Simmonds on a Perisher exercise aboard HMS Talent BRAD WAKEFIELD Standing between Russia’s increasingly assertive Northern Fleet submarines and British shores are the Royal Navy submarine captains, deemed the most “feared” in the world by Tom Clancy, the author of The Hunt for Red October. Their reputation is based on the officers’ ability to push a boat and her crew confidently to the very edge of what each is capable of, acting aggressively but without becoming rash or endangering the lives of those on board. These skills are honed on an infamously brutal command course, a century old this year, known within the service as “Perisher”, because the 35 per cent who fail can never serve underwater again, making a decade’s sea preparation redundant. Perisher is knowingly unforgiving; the submarine service’s responsibilities are too complex, perilous and crucial to British defence for it not to be. In addition to keeping the nuclear deterrent on permanent patrol, its other key tasks include the launching of cruise-missile attacks, the planting of boats off enemy shores to soak up intelligence, and covertly deploying the Special Boat Service. Those running the operations must be devoid of fear — and they are. “The underwater world is still very largely impenetrable. And, as long as that remains so, it will dominate the surface of the sea, and the sky above, and the space above that,” says Admiral Sir George Zambellas, the former First Sea Lord. -

2016 NAVAL SUBMARINE LEAGUE CORPORATE MEMBERS 5 STAR LEVEL Bechtel Nuclear, Security & Environmental (BNI) (New in 2016) BWX Technologies, Inc

NAVAL SUBMARINE LEAGUE TH 34 ANNUAL SYMPOSIUM SPONSORS L-3 COMMUNICATIONS NEWPORT NEWS SHIPBUILDING-A DIVISION OF HUNTINGTON INGALLS INDUSTRIES GENERAL DYNAMICS—ELECTRIC BOAT GENERAL DYNAMICS—MISSION SYSTEMS HUNT VALVE COMPANY, INC. LOCKHEED MARTIN CORPORATION NORTHROP GRUMMAN NAVIGATION & MARITIME SYSTEMS DIVISION RAYTHEON COMPANY AECOM MANAGEMENT SERVICES GROUP BAE SYSTEMS BWX TECHNOLOGIES, INC. CURTISS-WRIGHT CORPORATION DRS TECHNOLOGIES, MARITIME AND COMBAT SUPPORT SYSTEMS PROGENY SYSTEMS, INC. TREADWELL CORPORATION TSM CORPORATION ADVANCED ACOUSTIC CONCEPTS BATTELLE BOEING COMPANY BOOZ ALLEN HAMILTON CEPEDA ASSOCIATES, INC. CUNICO CORPORATION & DYNAMIC CONTROLS, LTD. GENERAL ATOMICS IN-DEPTH ENGINEERING, INC. OCEANEERING INTERNATIONAL, INC. PACIFIC FLEET SUBMARINE MEMORIAL ASSOC., INC. SONALYSTS, INC. SYSTEMS PLANNING AND ANALYSIS, INC. ULTRA ELECTRONICS 3 PHOENIX ULTRA ELECTRONICS—OCEAN SYSTEMS, INC. 1 2016 NAVAL SUBMARINE LEAGUE WELCOME TO THE 34TH ANNUAL SYMPOSIUM TABLE OF CONTENTS SYMPOSIUM SPEAKERS BIOGRAPHIES ADM FRANK CALDWELL, USN ................................................................................ 4 VADM JOSEPH TOFALO, USN ................................................................................... 5 RADM MICHAEL JABALEY, USN ............................................................................. 6 MR. MARK GORENFLO ............................................................................................... 7 VADM JOSEPH MULLOY, USN ................................................................................. -

Book Reviews John Bradford

Naval War College Review Volume 71 Article 11 Number 1 Winter 2018 Book Reviews John Bradford Matt olN and Follow this and additional works at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review Recommended Citation Bradford, John and Noland, Matt (2018) "Book Reviews," Naval War College Review: Vol. 71 : No. 1 , Article 11. Available at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review/vol71/iss1/11 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Naval War College Review by an authorized editor of U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Bradford and Noland: Book Reviews BOOK REVIEWS EVERYTHING OLD IS NEW AGAIN—EXCEPT WHAT’S NEW Japan’s Security Renaissance: New Policies and Politics for the Twenty-First Century, by Andrew L� Oros� New York: Columbia Univ� Press, 2017� 320 pages� $90� Andrew Oros, director of international both transitional eras were marked by studies at Washington College, opens significant advances in communications his new book provocatively, proclaim- technology that enabled a more rapid ing that in security policy “Japan is exchange of ideas and greater access back �” He then describes a series of for previously marginalized sections government decisions made in the of society to participate in political last decade that indicate a shift away discourse� In Europe, this technology from Japan’s postwar reliance on was the movable-type printing press; -

Introduction M P a C T Report

Back Cover Front Cover IIntroduction m p a c t Report Enterprise and Adventure 2010 The National Museum of the Royal Navy and HMS Victory HM Naval Base (PP66), Portsmouth, Hampshire PO1 3NH The NMRN is a charity registered in the United Kingdom (No. 1126283) and a company limited by guarantee registered in England (No. 6699696). Inside Front Cover Page 1 Trustees and Staff Contents Admiral Sir Peter Abbott GBE KCB (Chairman) Introduction 2 Admiral Sir Jonathan Band GCB Vice Admiral Sir Alan Massey KCB, CBE, ADC Major Achievements 4 Rear Admiral Roger Lane-Nott CB Rear Admiral Terry Loughran CB Use of Funds 6 Major General David Pennefather CB OBE Governance 8 Sir Robert Crawford CBE Dame Mary Fagan DCVO JP Visitor Services 10 Mr John Brookes Professor John Craven Learning and Access 11 Mr Barry Miller Collections and Scholarship 12 Mr Neil Davidson Partnerships 14 Director General: Dr Dominic Tweddle Navy 16 Future Projects 18 Page 2 Page 3 Introduction The National Museum of the Royal Navy formally came into existence in October 2008, an achievement representing the culmination of four years of hard work inaugurated by Sir Adrian Johns in his appointment as Second Sea Lord. The National Museum currently embraces the Royal Naval Museum, the Royal Navy Submarines Museum, the Royal Marines Museum and the Fleet Air Arm Museum. From the first of April we will be working in close partnership with HMS Victory, a relationship which will eventually see the visitor facing services provided my MoD transferred to the National Museum. The first Director General, Dr. -

Observations on Submarine Command

Ryan Ramsey, Lt Cdr RN N74 Submarine Development Squadron 12 [email protected] [email protected] I have had the privilege of serving for three submarine forces; The Royal Navy, The Royal Netherlands Navy and now the United States Navy. I am Command qualified, having completed the Royal Navy submarine Command course in 2000. In my 14 years submarine service thus far, I have served in 8 submarines (4 diesel submarines and 4 nuclear attack submarines), I have participated in 9 operational patrols, a variety of demanding operations at every level. I have driven a submarine in the absence of my Captain in restricted waters off Scotland. Most importantly to this paper, for three years I worked for Flag Officer Sea Training as a Command Rider. I provided warfare and navigational training to a variety of submarines, national and foreign, nuclear and diesel. I have been fortunate to witness the Command styles of ten UK Commanding Officers and nine foreign Navy Commanding Officers. In my present employment for Submarine Development Squadron 12, I have witnessed 9 US Commanding Officers and students on 4 submarine Command courses. 1. This generation of warfare is most complex. We have a great deal of information but still need to determine what is relevant and what is not. We need to be able to combat technologically similar enemies and in the worst case an enemy that is at least 100 years behind us; we must be able to create effect in environments not traditionally impacted on by submarines. Technology plays a part in the process of maintaining dominance; however I offer that in fact leadership will be the winning factor. -

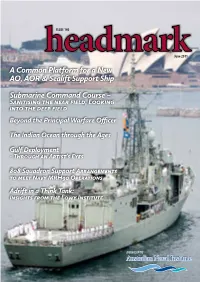

A Common Platform for a New AO, AOR

ISSUE 140 June 2011 A Common Platform for a New AO, AOR & Sealift Support Ship Submarine Command Course – Sanitising the near field, Looking into the deep field Beyond the Principal Warfare Officer The Indian Ocean through the Ages Gulf Deployment - Through an Artist’s Eyes 808 Squadron Support Arrangements to meet Navy MRH90 Operations Adrift in a Think Tank: Insights from the Lowy Institute JOURNAL OF THE Issue 140 3 Letters to the Editor Contents Dear Editor, As a member of the Naval Historical I enjoyed the article in Issue 138 Advisory Committee responsible for A Common Platform for a New AO, December 2010 by Midshipman overseeing the selection process for the AOR & Sealift Support Ship 4 Claire Hodge on RAN Helicopter names of future RAN ships I was very Flight Vietnam but must correct her interested to read the article written by Submarine Command Course – Note 2, where she states that SEA LCDR Paul Garai, RAN, which appears Sanitising the near field, Looking into DRAGON was the RAN’s principal in Headmark Issue 138, concerning the deep field 7 commitment during the Vietnam war, giving more meaningful names to the and the ships involved were HMA two new LHD’s. Beyond the Principal Warfare Officer 13 Ships Hobart, Vendetta and Brisbane. When viewing the article I was SEA DRAGON was the surprised to read that the RAN The Indian Ocean through the Ages 20 interdiction of supply routes and had previously named a destroyer logistic craft along the coast of North Gallipoli. This is a misleading Studies in Trait Leadership – Loved Vietnam from the DMZ to the Red comment. -

Kevin Le Page

SPEAKER BIO #1 – COMMODORE R J ANSTEY. ASSISTANT CHIEF OF STAFF (SUBMARINES) / DEPUTY FLAG OFFICER SCOTLAND AND NORTHERN IRELAND Born in Plymouth in 1968, Commodore Bob joined the Royal Navy in 1986 direct from school. He initially began Fleet training on HMS ANLESEY and HMS ARK ROYAL before volunteering for service in submarines during his subsequent Officer of the Watch course. In 1989 he joined HMS DOLPHIN for basic submarine training later that year. Spending his early submarine career in Trafalgar Class fast attack submarines (HMS TORBAY, HMS TIRLESS and HMS TRAFALGAR), he was involved in a series of exciting operations, spanning: Cold War patrols in the North Atlantic; supporting wider operations in the Adriatic and Gulf; and, in 1996, a submerged trip to the North Pole followed by a 9-month circumnavigation of the globe via both the Suez and Panama Canals. Following a period ashore as a senior instructor at the Royal Navy’s Submarine School, he completed the infamous Submarine Command Course (‘Perisher’) and changed stream to the Vanguard Class ballistic missile carrying submarine force. He served as the Executive Officer, and Second in Command, of HMS VICTORIOUS and HMS VENGEANCE before joining the staff of Flag Officer Sea Training as the Submarine Command Sea Rider. Selected for Command in May 2004, he went on to complete three strategic deterrent patrols as the Commanding Officer of HMS VIGILANT. After fifteen years as a deep specialist submariner, Bob enjoyed a succession of rewarding postings as: Directing Staff at the Advanced Command and Staff Course; a maritime desk officer in the Operations Directorate of the Ministry of Defence; the UK’s Submarine Operations Officer, directing all UK submarine operations; and the Successor SSBN desk officer in the Nuclear Capability area of the Ministry of Defence. -

Kevin Le Page

SPEAKER BIO #1 – COMMODORE R J ANSTEY. ASSISTANT CHIEF OF STAFF (SUBMARINES) / DEPUTY FLAG OFFICER SCOTLAND AND NORTHERN IRELAND Born in Plymouth in 1968, Commodore Bob joined the Royal Navy in 1986 direct from school. He initially began Fleet training on HMS ANLESEY and HMS ARK ROYAL before volunteering for service in submarines during his subsequent Officer of the Watch course. In 1989 he joined HMS DOLPHIN for basic submarine training later that year. Spending his early submarine career in Trafalgar Class fast attack submarines (HMS TORBAY, HMS TIRLESS and HMS TRAFALGAR), he was involved in a series of exciting operations, spanning: Cold War patrols in the North Atlantic; supporting wider operations in the Adriatic and Gulf; and, in 1996, a submerged trip to the North Pole followed by a 9-month circumnavigation of the globe via both the Suez and Panama Canals. Following a period ashore as a senior instructor at the Royal Navy’s Submarine School, he completed the infamous Submarine Command Course (‘Perisher’) and changed stream to the Vanguard Class ballistic missile carrying submarine force. He served as the Executive Officer, and Second in Command, of HMS VICTORIOUS and HMS VENGEANCE before joining the staff of Flag Officer Sea Training as the Submarine Command Sea Rider. Selected for Command in May 2004, he went on to complete three strategic deterrent patrols as the Commanding Officer of HMS VIGILANT. After fifteen years as a deep specialist submariner, Bob enjoyed a succession of rewarding postings as: Directing Staff at the Advanced Command and Staff Course; a maritime desk officer in the Operations Directorate of the Ministry of Defence; the UK’s Submarine Operations Officer, directing all UK submarine operations; and the Successor SSBN desk officer in the Nuclear Capability area of the Ministry of Defence. -

The British Expedition to Somaliland in 1904

ISSUE 150 DECEMBER 2013 The British expedition to Somaliland in 1904: A case study of the use of logistics The Key Drivers Behind China’s Naval Modernisation and their Consequences for Regional Security The Importance of Audience Perception in Communications from the Maritime Battlespace Environment of the Future Speech from Chief of Army, Seapower 2013 RN / RAN Junior Officer Development: Comparisons and Contrasts Australia-Indonesia: Towards a Maritime Strategic Partnership Scurvy: A Story of Medical Adventure & Bureaucratic Nonsense JOURNAL OF THE International Fleet Review Special Edition Issue 150 3 Letter to the Editor Contents Dear Editor, strong tides off Rabaul. International Fleet Review Tax Deductions and With Sydney, Centaur and the Sydney - October 2013 4 Donors for AE1 Search nation’s other naval wrecks having been The Australian Taxation Act was found it is appropriate for the nation now The British expedition to Somaliland amended in July 2013 to give AE1 to find its first loss and properly honour in 1904: A case study of the use of Incorporated a Deductible Gift Recipient those lost in her. Donors are sought for logistics 15 (DGR) status. It was announced by the the search and they are requested to th Minister for Defence on 14 September be in touch with Honorary Treasurer The Key Drivers Behind China’s Naval 2011, shortly before the commemoration Michael Dunne by email to mbdunne@ Modernisation and their Consequences ceremony and unveiling of a plaque bigpond.com. for Regional Security 18 to AE1 at the Garden island Heritage Michael White Centre, Sydney, that AE1 Inc. would have President, AE1 Incorporated The Importance of Audience DGR status for three years from that date Brisbane Perception in Communications but it has taken until now for the Act to from the Maritime Battlespace be amended to this effect. -

Archived Content Information Archivée Dans Le

Archived Content Information identified as archived on the Web is for reference, research or record-keeping purposes. It has not been altered or updated after the date of archiving. Web pages that are archived on the Web are not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards. As per the Communications Policy of the Government of Canada, you can request alternate formats on the "Contact Us" page. Information archivée dans le Web Information archivée dans le Web à des fins de consultation, de recherche ou de tenue de documents. Cette dernière n’a aucunement été modifiée ni mise à jour depuis sa date de mise en archive. Les pages archivées dans le Web ne sont pas assujetties aux normes qui s’appliquent aux sites Web du gouvernement du Canada. Conformément à la Politique de communication du gouvernement du Canada, vous pouvez demander de recevoir cette information dans tout autre format de rechange à la page « Contactez-nous ». CANADIAN FORCES COLLEGE / COLLÈGE DES FORCES CANADIENNES CSC 33 / CCEM 33 MASTER OF DEFENCE STUDIES The Court Martial of Lieutenant-Commander Dean Marsaw: Lessons on Culture, Leadership, and Accountability for the CF By /par Cdr M.E. Clark This paper was written by a student La présente étude a été rédigée par un attending the Canadian Forces College stagiaire du Collège des Forces in fulfilment of one of the requirements canadiennes pour satisfaire à l'une des of the Course of Studies. The paper is a exigences du cours. L'étude est un scholastic document, and thus contains document qui se rapporte au cours et facts and opinions, which the author contient donc des faits et des opinions alone considered appropriate and que seul l'auteur considère appropriés et correct for the subject. -

Canadian Military Journal, Issue 14, No 3

Vol. 14, No. 3, Summer 2014 CONTENTS 3 EDITOR’S CORNER 4 LETTERS TO THE EDITOR CANADA’S NAVY 7 Does Canada Need Submarines? by Michael Byers 15 The Contribution of Submarines to Canada’s Freedom of Action on the Cover World Stage Landing of the First Canadian by Paul T. Mitchell Division at Saint-Nazaire, by Edgar Bundy Rutherford MILITARY INTELLIGENCE Canadian War Museum 19710261-0110 26 The Past, Present and Future of Chinese Cyber Operations by Jonathan Racicot SENIOR CIVIL SERVANTS AND NATIONAL DEFENCE 38 Unelected, Unarmed Servants of the State: The Changing Role of Senior Civil Servants inside Canada’s National Defence by Daniel Gosselin MILITARY HISTORY 53 Know Your Ground: A Look at Military Geographic Intelligence and Planning in the Second World War by Lori Sumner 64 The Colonial Militia of Vancouver Island and British Columbia 1853–1871 Does Canada Need by Adam Goulet Submarines? VIEWS AND OPINIONS 70 The Duty to Remember is an Integral Part of Bilateral Relations by Marcel Cloutier 73 Whatever Happened to Mission Command in the CAF? by Allan English 76 Compulsory Release and Duty of Fairness by Kostyantyn Grygoryev COMMENTARY 80 The Aurora Chronicles by Martin Shadwick JOURNAL REVIEW ESSAY The Past, Present and 85 Situational Awareness Depends upon Intelligence Gathering, but Good Future of Chinese Preparation Depends upon Knowledge of the Issues Cyber Operations by Sylvain Chalifour 86 BOOK REVIEWS Canadian Military Journal / Revue militaire canadienne is the official professional journal of the Canadian Armed Forces and the Department of National Defence. It is published quarterly under authority of the Minister of National Defence. -

In Depth No 72

~ 1 ~ IN DEPTH Official Newsletter of the Submariners Association Patron: Admiral of the Fleet Lord Boyce KG GCB OBE DL Issue No: 72 www.submarinersassociation.co.uk April 2021 In This Issue – A Selection of the Items Pages 2 - 3 Editorial & Chairman’s Report Pages 4 - 6 New & Re-Joining Members Pages 6 - 7 Submarine losses of WWII Pages 7 - 8 SM Trainees Passing out Parades Pages 9 - 14 RN Submarine News Pages 14 - 15 Royal Navy News Pages 15 - 16 HMS SLEUTH Pages 16 - 18 Submariners Memorial Appeal Pages 18 - 19 Submarine Family Fund Pages 20 - 21 Submariner VC Holder Pages 21 - 25 Miscellaneous Articles Pages 25 - 26 The K26 Story - Continued Pages 27 - 30 Crossed the Bar ~ 2 ~ PRESIDENT Rear Admiral Niall Kilgour CB The Submariner “Of all the branches of men in the Forces there is none which shows more devotion and faces grimmer perils than the Submariner; great deeds are done in the air and on the land, nevertheless nothing surpasses your exploits.” Sir Winston Churchill 1943 ________________________________________________________________________________________ NATIONAL COMMITTEE _________________________________________________________________________________ Chairman: Secretary: Membership Secretary: B.K. (Barrie) Downer I.W. (Ian) Vickers Esq. David Woolterton The Firs, Dundalk Street 160, Bradshaw Meadows 2, Thornton Close Barrow Island Bradshaw Alresford Barrow in Furness Bolton Hampshire Cumbria LA14 2RZ Lancs. BL2 4ND SO24 9FE Tel: 01229 820963 Tel: 01204 308539 Tel: 01962 734940 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Vice Chairman: Treasurer: Newsletter Editor: I.M.(Iain) Mackenzie, MBE A.Bain Barrie Downer April Cottage 5, Rydal Mount The Firs, Dundalk Street 41, Grafton Road Belthorn Barrow Island Worthing, Lancs.