Deception Through Telling the Truth?!: Experimental Evidence from Individuals and Teams

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE INTERNATIONAL SUMMER SCHOOL in INNSBRUCK, AUSTRIA the INTERNATIONAL SUMMER SCHOOL

DIVISION OF INTERNATIONAL EDUCATION THE INTERNATIONAL SUMMER SCHOOL in INNSBRUCK, AUSTRIA THE INTERNATIONAL SUMMER SCHOOL June 29 - August 9, 2013 UNO and the University of Innsbruck receive the Euro-Atlantic Culture Award for International Education This prestigious prize was awarded to the University of New Orleans and the University of Innsbruck for “their remarkable contribution to the scientific and cultural exchange between Europe and the USA.” The European Foundation for Culture “Pro Europa” supports cooperation in the areas of art and science between the European Union and the United States. The International Summer School is the cornerstone of the long-standing friendship between UNO and the University of Innsbruck. WELCOME TO THE INNSBRUCK INTERNATIONAL SUMMER SCHOOL The University of New Orleans is proud to welcome you to the 38th session of The Innsbruck International Summer School. International study programs exist not only to fulfill your educational needs, but to introduce you to the unique and enriching attributes of foreign cultures. As you immerse yourself in the activities of your host culture, remember that, through your participation in this program, you serve as a cultural ambassa- dor for your university and the United States. I hope that this summer your worldview will be expanded and your taste for travel will be nurtured. Again, welcome, and enjoy your summer abroad! Dr. Peter J. Fos, President, The University of New Orleans Welcome to The Innsbruck International Summer School. I know you will enjoy your time in Austria and the opportunities you will have to learn about Europe both in the classroom and while traveling. -

International Students Guide

International Students Guide Printed with support of the European Commission Welcome Congratulations on choosing the University of Innsbruck for your studies abroad. Getting to know new people and places is an exciting experience and opens ones horizons beyond compare. We look forward to welcoming you and sincerely hope your stay in Austria will be a pleasant and rewarding one. This guide was primarily conceived with Socrates-Erasmus students in mind though we have tried our best to deal with the relevant issues for all incoming students and to eliminate every obstacle on your way to Innsbruck University. There is however always room for improvement and we are grateful for your suggestions and of course ready to help whenever necessary. International Office Foto: Gerhard Berger – 1 – Contents I. General Information ..............................................................................................3 II. University of Innsbruck ..........................................................................................7 III. Admission Procedures ..........................................................................................12 IV. Services for Incoming Students ............................................................................17 V. Students Facilities..................................................................................................22 VI. Everyday Life ........................................................................................................24 VII. Free Time Activities ..............................................................................................27 -

Innovative Learning Environments (ILE)

Directorate for Education Centre for Educational Research and Innovation (CERI), OECD Innovative Learning Environments (ILE) INVENTORY CASE STUDY New Secondary School Europaschule Linz Austria This secondary school is a pilot school affiliated with a university college of teacher education, and functions both as a centre for practical in-school training of teacher- students and as a school with the objective to offer (and empirically investigate) ideal learning conditions. The school has an emphasis on language learning and international contacts, but students can also choose a science, artistic or media focus. Students learn in flexible heterogeneous groupings, some of which are integrative. Teaching activities aim at ability differentiation and include open teaching during which students work with weekly work schedules. Individual feedback on performance and student behaviour is given in the form of portfolios which include teacher reports and student self-assessments. Based on the feedback, students can prepare a remedial instruction and resources plan with the objective that learning becomes self-managed and intrinsically motivated. This Innovative Learning Environment case study has been prepared specifically for the OECD/ILE project. Research has been undertaken by Ilse Schrittesser and Sabine Gerhartz from the University of Innsbruck under the supervision of Josef Neumueller from the Federal Ministry for Education, the Arts and Culture of Austria, following the research guidelines of the ILE project. © OECD, 2012. ©Federal Ministry -

Sociology and Organization Studies

978–0–19–953532–100-Adler-Prelims OUP352-Paul-Adler (Typeset by SPi, Delhi) i of xx September 30, 2008 13:55 the oxford handbook of SOCIOLOGY AND ORGANIZATION STUDIES classical foundations 978–0–19–953532–100-Adler-Prelims OUP352-Paul-Adler (Typeset by SPi, Delhi) ii of xx September 30, 2008 13:55 978–0–19–953532–100-Adler-Prelims OUP352-Paul-Adler (Typeset by SPi, Delhi) iii of xx September 30, 2008 13:55 the oxford handbook of ....................................................................................................................... SOCIOLOGY AND ORGANIZATION STUDIES classical foundations ....................................................................................................................... Edited by PAUL S. ADLER 1 978–0–19–953532–100-Adler-Prelims OUP352-Paul-Adler (Typeset by SPi, Delhi) iv of xx September 30, 2008 13:55 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford ox2 6dp Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York © Oxford University Press, 2009 Themoralrightsoftheauthorhavebeenasserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2009 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. -

Education Publications

________________________________________________________________________ Kevin J. Corcoran Professor of Philosophy Calvin College Dept. Of Philosophy 3201 Burton SE Grand Rapids, MI 49546 Office Phone: (616) 526-6636 e-mail: [email protected] ________________________________________________________________________ Education Ph.D. Philosophy, Purdue University, 1997 M.A. Philosophical Theology, Yale University (Magna Cum Laude), 1991 B.A. Philosophy and Social Work, University of Maryland Baltimore County (Magna Cum Laude), 1988 Publications Books • Rethinking Human Nature: A Christian Materialist Alternative to the Soul (Baker Academic, 2006) • Church in the Present Tense: A Candid Look at What’s Emerging. Co-authored with: Scot McKnight, Peter Rollins and Jason Clark (Brazos, 2011) • Minds, Brains and Persons: An Introduction to Key Issues in Consciousness Studies (In Process) Edited Books • Common Sense Metaphysics: Themes from the Philosophy of Lynne Rudder Baker (with Luis Oliveira; Routledge, forthcoming 2020) Authors include: Christopher Hill, Joseph Levine, John Perry, Janet Levin, Angela Mendelovici, Carolyn Dicey, Peter van Inwagen, Derk Pereboom, Kathrin Koslicki, Marya Schetchman, Louise Antony, Thomas Senor, Mario De Caro, Sam Cowling, Einar Bonn, Paul Manata, and Kevin Corcoran • Soul, Body and Survival: Essays on the Metaphysics of Persons, (Cornell University Press, 2001) Authors include: John Foster, Eric Olson, Jaegwon Kim, Timothy O’Connor, Charles Taliaferro, Stewart Goetz, William Hasker, Brian Leftow, E.J. Lowe, Lynne Baker, Trenton Merricks, John Cooper, Stephen T. Davis and Kevin Corcoran. Refereed Articles in Journals 14. “Persons, Bodies and Brains, Oh My!,” Special Issue of Philosophy, Theology and the Sciences (forthcoming, 2020). 13. “A Materialist View of Human Persons and Belief in an After Life,” Modern Believing 57:2 (2016). -

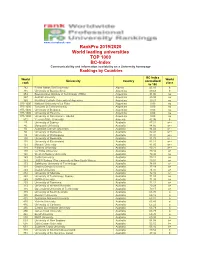

Rankpro 2019/2020 World Leading Universities TOP 1000 BC-Index Communicability and Information Availability on a University Homepage Rankings by Countries

www.cicerobook.com RankPro 2019/2020 World leading universities TOP 1000 BC-Index Communicability and information availability on a University homepage Rankings by Countries BC-Index World World University Country normalized rank class to 100 782 Ferhat Abbas Sétif University Algeria 45.16 b 715 University of Buenos Aires Argentina 49.68 b 953 Buenos Aires Institute of Technology (ITBA) Argentina 31.00 no 957 Austral University Argentina 29.38 no 969 Pontifical Catholic University of Argentina Argentina 20.21 no 975-1000 National University of La Plata Argentina 0.00 no 975-1000 Torcuato Di Tella University Argentina 0.00 no 975-1000 University of Belgrano Argentina 0.00 no 975-1000 University of Palermo Argentina 0.00 no 975-1000 University of San Andrés - UdeSA Argentina 0.00 no 812 Yerevan State University Armenia 42.96 b 27 University of Sydney Australia 87.31 a++ 46 Macquarie University Australia 84.66 a++ 56 Australian Catholic University Australia 84.02 a++ 80 University of Melbourne Australia 82.41 a++ 93 University of Wollongong Australia 81.97 a++ 100 University of Newcastle Australia 81.78 a++ 118 University of Queensland Australia 81.11 a++ 121 Monash University Australia 81.05 a++ 128 Flinders University Australia 80.21 a++ 140 La Trobe University Australia 79.42 a+ 140 Western Sydney University Australia 79.42 a+ 149 Curtin University Australia 79.11 a+ 149 UNSW Sydney (The University of New South Wales) Australia 79.01 a+ 173 Swinburne University of Technology Australia 78.03 a+ 191 Charles Darwin University Australia 77.19 -

Curriculum Vitae/Lebenslauf (Deutsch)

Curriculum Vitae/Lebenslauf (Deutsch) Geburtsdaten: Geb. 1946, Innsbruck, Österreich Familienstand: Verheiratet mit Isabella, geb. Lienhart, Sohn: Andreas (DI Mag. Dr. sub ausp.) Wohnort: A-6100 Seefeld/Tirol, Schulweg 744 Militärdienst: 1969 Schulbildung: 1952 - 1956: Volksschule Seefeld/Tirol 1956 - 1960: Hauptschule Innsbruck/Hötting 1960 - 1964: Bundeshandelsakademie Innsbruck (19.6.1964: Matura) Hochschulbildung: 1964 - 1968: Studium der ‘Volkswirtschaftslehre’, UniVersität Innsbruck; 1968: Graduierung ‘Diplom-Volkswirt’ 1971 - 1973: Studium der ‘Sozial- und Wirtschaftswissenschaften’, UniVersität Innsbruck; 1971: Sponsion „Mag.rer.soc.oec.“; 1973: Promotion „Dr.rer.soc.oec.“ (Diss: Transfers zwischen Gebietskörperschaften (Auszeichnung)) 1973 - 1974: Studien- und Forschungsaufenthalt London (London School of Economics and Political Science – LSE, GB) 1976 u. 1978: (Kurz-)Forschungsaufenthalte UniVersity of York (GB) 1982: Habilitation für das Fachgebiet Volkswirtschaftslehre unter bes. Berücksichtigung der Finanzwissenschaft (Schrift: Politökonomische Theorie des Föderalismus, Veröff. im Nomos-Verlag, Baden-Baden (D)) Berufungen/Ernennungen: 1987 - 2012: Universitätsprofessor (Extraordinarius/Ordinarius) für Volkswirtschaftslehre Unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der Finanzwissenschaft und Sportökonomik, Universität Innsbruck 1992 – 2004: Leiter der Abteilung „Regionale und kommunale Finanzpolitik, FinanZaus- gleich“ des Instituts für Finanzwissenschaft, UniVersität Innsbruck (Abänderung nach Strukturverschiebung) 1985: Vis. Fulbright -

Katherine Munn and Barry Smith), Frankfurt: Ontos, 2008

Katherine Dormandy (née Munn), DPhil [email protected] University of Innsbruck Karl-Rahner Platz 1 A-6020 Innsbruck, Austria +43 (0) 699 11 22 3092 www.katherinedormandy.com EDUCATION Oxford University, DPhil in Philosophy, December 2012. Dissertation: Rationality: An Expansive Bayesian Theory Oxford University, BPhil in Philosophy (2-year taught masters degree), July 2007. Leipzig University, Bachelors Degree in Philosophy, October 2005. Rutgers University, Bachelors Degree in English Literature, May 2003. EMPLOYMENT Project Leader, Lise-Meitner Grant from the Austrian Science Fund (FWF), ‘Emuna: Rationality and Religious Belief’, Institute for Christian Philosophy, University of Innsbruck, current. Research Grant Winner, Saint Louis University Templeton Project (based at the Institute for Christian Philosophy, University of Innsbruck), ‘The Philosophy and Theology of Intellectual Humility’, from June 2014-June 2015. (Project leaders: Eleonore Stump, John Greco) Post-Doc, Templeton Project ‘Analytic Theology’, Institute for Christian Philosophy, University of Innsbruck, April-May 2014. Junior Professor of Philosophy (fixed term), Humboldt University, Berlin, October 2013-April 2014. Post-Doc, Templeton Project ‘Analytic Theology’, Munich School of Philosophy (based at the Institute for Christian Philosophy, University of Innsbruck), February-October 2013. Various teaching engagements during postgraduate study at Oxford (see below). Academic Researcher, Institute for Formal Ontology and Medical Information Science (IFOMIS), University of Leipzig and University of Saarbrücken, Germany, August 2002-August 2005. PUBLICATIONS ‘Die Rationalität Religiöser Überzeugungen’ [‘The Rationality of Religious Beliefs’], forthcoming in the Handbuch für Analytische Theologie [Handbook of Analytic Theology], ed. Georg Gasser, Ludwig Jaskolla, and Thomas Schärtl, Aschendorff, January 2015. ‘Religious Evidentialism’ [winner, Paternoster Young Philosopher of Religion Prize, 2010], in the European Journal for Philosophy of Religion, Vol. -

International Student Guide

International Student Guide Leopold-Franzens-Universität International Students Guide Page 1 Welcome Congratulations on choosing the University of Innsbruck for your studies abroad. Our university offers a full programme of studies. You have chosen a university not only at the centre of the Alps but also at the centre of Europe! Starting from Innsbruck you can take a day trip to Vienna, Salzburg, Venice or Munich. Getting to know new people and places is an exciting experience and opens ones horizons beyond compare. We look forward to welcoming you and sincerely hope your stay in Austria will be a pleasant and rewarding one. This guide was primarily conceived with Erasmus students in mind though we have tried our best to deal with the relevant issues for all incoming students and to eliminate every obstacle on your way to the University of Innsbruck. We are here to lend a helping hand whenever necessary. There is however always room for improvement and we are grateful for your suggestions. The Erasmus Team of the International Office International Students Guide Page 2 Contents I. GENERAL INFORMATION 4 II. UNIVERSITY OF INNSBRUCK 7 III. ADMISSION PROCEDURES 12 IV. SERVICES FOR INCOMING STUDENTS 17 V. STUDENTS SUPPORT 19 VI. STUDENTS FACILITIES 21 VII. EVERYDAY LIFE 23 VIII. FREE TIME ACTIVITIES 25 IX. CHECK LIST FOR ERASMUS/EXCHANGE STUDENTS 29 X. CHECK LIST FOR NON-EXCHANGE STUDENTS 30 XI. ERASMUS DEPARTMENTAL COORDINATORS 31 XII. USEFUL ADDRESSES 33 International Students Guide Page 3 I. General Information Geography Austria lies at the very heart of southern Central Europe having common borders with eight other countries and covers a total area of 84.000 km2 making it a little larger than Scotland and smaller than Portugal. -

University of Innsbruck (UIBK)

University of Innsbruck (UIBK) Contact information Head of the International Relations Office Tel.: 0043 512 507 32400 Mathias Schennach [email protected] International Mobility & Networks Incomings and Outgoings except Business and Economics: Incomings Tel.: 0043 512 507 32402 Katharina Walch [email protected] Outgoings Tel.: 0043 512 507 32401 Christina Plattner [email protected] PLEASE NOTE: The School of Management has a separate office, called International Economic and Business Studies Office (IWW – office). If you nominate students with a major in Business and Economics please refer to [email protected] Website for Incomings (IWW office): https://www.uibk.ac.at/iww/incomings/ IWW Office Incomings Tel.: 0043 512 507 73182 Mag. Christoph Kornberger [email protected] Outgoings Tel.: 0043 512 507 73180 Mag. Elke Kitzelmann [email protected] 1 Partner information 2021/2022 University of Innsbruck Website for Incoming Students (all faculties, except School of You will find more details on the following website: Management) https://www.uibk.ac.at/international-relations/exchange-students- incoming/index.html.en Academic Calendar (lecture and examination period) 1st semester: 4th October 2021 – 5th February 2022 2nd semester: 7st March 2022 – 2ndJuly 2022 Examination period: last week of the semester – however some exams can be held later. The student must read the course description (“Details”). Application Requirements for Incoming students Information regarding online Application https://www.uibk.ac.at/international-relations/exchange-students- -

Institutions

Published on Eurydice (https://eacea.ec.europa.eu/national-policies/eurydice) Hints: The link GND offers the German standard data base for institutional names. Please scroll down to point 9 for a German list of institutions. Public Bodies . Austrian Federal Chancellery =Österreich / Bundeskanzleramt (BKA) GND [1] Mail contact [2] / Website: German [3] English [4] Address: Ballhausplatz 2, 1014 Wien, Tel: +43-1-53115-0 Type: Public Body The Federal Chancellery plays a central role in the Austrian government. The Austrian Federal Chancellery is responsible for coordinating general government policy, the public information activities of the Federal Government, and the Federal Constitution. It also represents the Republic of Austria vis-à-vis the Constitutional Court, the Administrative Court, and international law courts. Moreover, the Federal Chancellery has responsibility for special matters such as bioethics, building culture, data protection, growth and jobs, public services, OECD - Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, security policy. The head of the Austrian Federal Chancellery is the Federal Chancellor. The Federal Chancellery also comprises the Federal Minister within the Federal Chancellery for the EU and Costitution as well as the Federal Minister within the Federal Chancellery for Women and Integration, Austrian Federal Minister for Women, Family, Youth and Integration in the Federal Chancellery =Österreich / Bundesministerin für Frauen, Familie, Jugend und Integration im Bundeskanzleramt Mailcontact [5] / Website (family and youth [6]) [6] / Website Minister [7] Address: Untere Donaustraße 13-15, 1020 Wien, Tel.: +43 1 531 15-0 and +43 1 711 00-0 Type: Public Body The Minister (Susanne Raab) for Women, Family, Youth and Integraton includes responsibility for childcare benefits, family allowance and for providing the necessary framework to ensure a work-life balance. -

6Th Workshop on Experimental Economics for the Environment University of Innsbruck, June 10-11Th 2021

6th Workshop on Experimental Economics for the Environment University of Innsbruck, June 10-11th 2021 Online Workshop The workshop can be accessed online and the link to the virtual meeting held in gather.town and Zoom will be distributed a few days before the workshop. Registration for the workshop is free. To attend the workshop, please register at www.exp4env.com before May 31st. Program at Glance Thursday 10th June 20201 9.00-9.15h Welcome address 9.15-10.45h Keynote presentation by Lata Gangadharan “Social Dilemmas, Inequality and Compliance: Evidence from Experiments” 10.45-11.15h Coffee Break 11.15-12.45h Parallel Sessions: Session 1 – Regulation, Session 2 – Behavior over time 12.45-13.00h Open Discussion for Session 1 & 2 14.00-16.00h Private Meetings Friday 11th June 2021 9.00-10.30h Parallel Sessions: Session 3 – Energy, Session 4 – Pro-Environmental Behavior 1.45-11.15h Open Discussion for Session 3 & 4 10.45-11.15 Coffee Break 11.15-12.45 Parallel Sessions: Session 5 – Social Information, Session 6 – Voluntary Policies 12.45-13.00h Open Discussion Session 5 & 6 14.00-16.00h Private Meetings Regulations for Parallel Sessions Each presenter has a 30 min slot, with a suggested distribution of time of 20 min presentation followed by 10 minutes discussion. Timing will be enforced strictly thus participants can also change between parallel sessions. At the end of each parallel session, the parallel session rooms will be available for additional 15 minutes of an open discussion. Presentations include projects at the stage of Working Paper, Results or Protocol.