Final Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sites of Botanical Significance Vol1 Part1

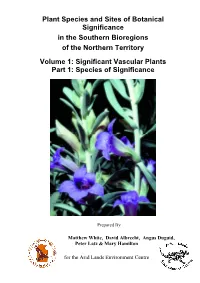

Plant Species and Sites of Botanical Significance in the Southern Bioregions of the Northern Territory Volume 1: Significant Vascular Plants Part 1: Species of Significance Prepared By Matthew White, David Albrecht, Angus Duguid, Peter Latz & Mary Hamilton for the Arid Lands Environment Centre Plant Species and Sites of Botanical Significance in the Southern Bioregions of the Northern Territory Volume 1: Significant Vascular Plants Part 1: Species of Significance Matthew White 1 David Albrecht 2 Angus Duguid 2 Peter Latz 3 Mary Hamilton4 1. Consultant to the Arid Lands Environment Centre 2. Parks & Wildlife Commission of the Northern Territory 3. Parks & Wildlife Commission of the Northern Territory (retired) 4. Independent Contractor Arid Lands Environment Centre P.O. Box 2796, Alice Springs 0871 Ph: (08) 89522497; Fax (08) 89532988 December, 2000 ISBN 0 7245 27842 This report resulted from two projects: “Rare, restricted and threatened plants of the arid lands (D95/596)”; and “Identification of off-park waterholes and rare plants of central Australia (D95/597)”. These projects were carried out with the assistance of funds made available by the Commonwealth of Australia under the National Estate Grants Program. This volume should be cited as: White,M., Albrecht,D., Duguid,A., Latz,P., and Hamilton,M. (2000). Plant species and sites of botanical significance in the southern bioregions of the Northern Territory; volume 1: significant vascular plants. A report to the Australian Heritage Commission from the Arid Lands Environment Centre. Alice Springs, Northern Territory of Australia. Front cover photograph: Eremophila A90760 Arookara Range, by David Albrecht. Forward from the Convenor of the Arid Lands Environment Centre The Arid Lands Environment Centre is pleased to present this report on the current understanding of the status of rare and threatened plants in the southern NT, and a description of sites significant to their conservation, including waterholes. -

Lamiales – Synoptical Classification Vers

Lamiales – Synoptical classification vers. 2.6.2 (in prog.) Updated: 12 April, 2016 A Synoptical Classification of the Lamiales Version 2.6.2 (This is a working document) Compiled by Richard Olmstead With the help of: D. Albach, P. Beardsley, D. Bedigian, B. Bremer, P. Cantino, J. Chau, J. L. Clark, B. Drew, P. Garnock- Jones, S. Grose (Heydler), R. Harley, H.-D. Ihlenfeldt, B. Li, L. Lohmann, S. Mathews, L. McDade, K. Müller, E. Norman, N. O’Leary, B. Oxelman, J. Reveal, R. Scotland, J. Smith, D. Tank, E. Tripp, S. Wagstaff, E. Wallander, A. Weber, A. Wolfe, A. Wortley, N. Young, M. Zjhra, and many others [estimated 25 families, 1041 genera, and ca. 21,878 species in Lamiales] The goal of this project is to produce a working infraordinal classification of the Lamiales to genus with information on distribution and species richness. All recognized taxa will be clades; adherence to Linnaean ranks is optional. Synonymy is very incomplete (comprehensive synonymy is not a goal of the project, but could be incorporated). Although I anticipate producing a publishable version of this classification at a future date, my near- term goal is to produce a web-accessible version, which will be available to the public and which will be updated regularly through input from systematists familiar with taxa within the Lamiales. For further information on the project and to provide information for future versions, please contact R. Olmstead via email at [email protected], or by regular mail at: Department of Biology, Box 355325, University of Washington, Seattle WA 98195, USA. -

No. 120 SEPTEMBER 2004 Price: $5.00 Australian Systematic Botany Society Newsletter 120 (September 2004)

No. 120 SEPTEMBER 2004 Price: $5.00 Australian Systematic Botany Society Newsletter 120 (September 2004) AUSTRALIAN SYSTEMATIC BOTANY SOCIETY INCORPORATED Council President Vice President Stephen Hopper John Clarkson School of Plant Biology Centre for Tropical Agriculture University of Western Australia PO Box 1054 CRAWLEY WA 6009 MAREEBA, Queensland 4880 tel: (08) 6488 1647 tel: (07) 4048 4745 email: [email protected] email: [email protected] Secretary Treasurer Brendan Lepschi Anna Munro Centre for Plant Biodiversity Research Centre for Plant Biodiversity Research Australian National Herbarium Australian National Herbarium GPO Box 1600 GPO Box 1600 CANBERRA ACT 2601 CANBERRA ACT 2601 tel: (02) 6246 5167 tel: (02) 6246 5472 email: [email protected] email: [email protected] Councillor Councillor Darren Crayn Marco Duretto Royal Botanic Gardens Sydney Tasmanian Herbarium Mrs Macquaries Road Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery SYDNEY NSW 2000 Private Bag 4 tel: (02) 9231 8111 HOBART , Tasmania 7001 email: [email protected] tel.: (03) 6226 1806 email: [email protected] Other Constitutional Bodies Public Officer Hansjörg Eichler Research Committee Kirsten Cowley Barbara Briggs Centre for Plant Biodiversity Research Rod Henderson Australian National Herbarium Betsy Jackes GPO Box 1600, CANBERRA ACT 2601 Tom May tel: (02) 6246 5024 Chris Quinn email: [email protected] Chair: Vice President (ex officio) Affiliate Society Papua New Guinea Botanical Society ASBS Web site www.anbg.gov.au/asbs Webmaster: Murray Fagg Centre for Plant Biodiversity Research Australian National Herbarium Email: [email protected] Loose-leaf inclusions with this issue · None Publication dates of previous issue Austral.Syst.Bot.Soc.Nsltr 119 (June 2004 issue) Hardcopy: 20th August 2004; ASBS Web site 24th August 2004 Australian Systematic Botany Society Newsletter 120 (September 2004) ASBS Inc. -

A Synoptical Classification of the Lamiales

Lamiales – Synoptical classification vers. 2.0 (in prog.) Updated: 13 December, 2005 A Synoptical Classification of the Lamiales Version 2.0 (in progress) Compiled by Richard Olmstead With the help of: D. Albach, B. Bremer, P. Cantino, C. dePamphilis, P. Garnock-Jones, R. Harley, L. McDade, E. Norman, B. Oxelman, J. Reveal, R. Scotland, J. Smith, E. Wallander, A. Weber, A. Wolfe, N. Young, M. Zjhra, and others [estimated # species in Lamiales = 22,000] The goal of this project is to produce a working infraordinal classification of the Lamiales to genus with information on distribution and species richness. All recognized taxa will be clades; adherence to Linnaean ranks is optional. Synonymy is very incomplete (comprehensive synonymy is not a goal of the project, but could be incorporated). Although I anticipate producing a publishable version of this classification at a future date, my near-term goal is to produce a web-accessible version, which will be available to the public and which will be updated regularly through input from systematists familiar with taxa within the Lamiales. For further information on the project and to provide information for future versions, please contact R. Olmstead via email at [email protected], or by regular mail at: Department of Biology, Box 355325, University of Washington, Seattle WA 98195, USA. Lamiales – Synoptical classification vers. 2.0 (in prog.) Updated: 13 December, 2005 Acanthaceae (~201/3510) Durande, Notions Elém. Bot.: 265. 1782, nom. cons. – Synopsis compiled by R. Scotland & K. Vollesen (Kew Bull. 55: 513-589. 2000); probably should include Avicenniaceae. Nelsonioideae (7/ ) Lindl. ex Pfeiff., Nomencl. -

Glossary of Terms

Appendix A Glossary of Terms Nolans Bore Mine Notice of Intent 126 Glossary of Terms Term Description 232Th An isotope of the element Thorium 238U An isotope of the element Uranium AAPA Aboriginal Areas Protection Authority ADG Australian Code for the Transport of Dangerous Goods by Road and Rail, 6th edition, 1998. ANSTO Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Organisation ARI The Average Recurrence Interval is the average, or expected, value of the periods between exceedances of a given rainfall total accumulated over a given duration ARPANSA Australian Radiation Protection and Nuclear Safety Agency AS Australian Standards BCM Bank Cubic Metre is a measure of the in-situ volume of a material Bench A landform consisting of a long strip of land at constant height in an otherwise sloped area. Benign waste Process or mining waste that is benign to the environment BoM Bureau of Meteorology Bulk density The weight of material (including solid particles and any contained water) per unit volume including water. Ca Calcium Calcium chloride An ionic compound of calcium and chlorine. (CaCl2) CAPEX Capital Expenditure CBR California Bearing Ratio Cheralite (CaTh[PO4]2). The dominant member of the Monazite group. Cl Chlorine CLC Central Land Council Cut-off A specified value below which ore becomes uneconomic for the operator to extract DBIRD Northern Territory Department of Business, Industry and Resource Development DCF Discounted Cash Flow DEH Division of Environment, Heritage and the Arts DN 100 Pipes with a Nominal Diameter of 100 millimetres Nolans Bore Mine Notice of Intent 127 Drill & blast A method in which holes are drilled for explosive charges. -

Plant Life of Western Australia

PART V The Flora of extra-tropical Western Australia and it’s classification. CHAPTER I. FLORISTIC SUBDIVISION OF THE REGION To correctly interpret the interesting floristic features of south-western Australia, the extensive use of statistical data is required. Since, however, such data are as yet inadequate, the best one can do is to provide a suitable foundation to enable a critical study of the facts. I have therefore examined and assessed all my data so as to achieve a uniform standard. The fact that these figures may be subject to considerable change in the future does not affect their usefulness. This was made clear by J. D. Hooker when he said “it is not from a consideration of specific details that such problems as those of the relationships between Floras and the origin and distribution of organic forms will ever be solved, although we must eventually look at these details for proofs of the solu- tions we propose”. The division of extra-tropical Western Australia into two distinct regions i.e. the Eremaean and the Southwest Province, has so far received most attention. Their ap- proximate boundaries were first recorded by Ferdinand von Müller. In several of his publications he refers to the importance of a line running from Shark Bay to the west side of the Great Bight, as separating the two Provinces. This line coincides, more or less , with the 30 cm isohyet which divides the arid interior from the coastal region. This line is also important from the standpoint of land settlement since it also marks the limit of the area where wheat can be successfully grown. -

Flora of Australia, Volume 29, Solanaceae

FLORA OF AUSTRALIA Volume 29 Solanaceae This volume was published before the Commonwealth Government moved to Creative Commons Licensing. © Commonwealth of Australia 1982. This work is copyright. You may download, display, print and reproduce this material in unaltered form only (retaining this notice) for your personal, non-commercial use or use within your organisation. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced or distributed by any process or stored in any retrieval system or data base without prior written permission from the copyright holder. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to: [email protected] FLORA OF AUSTRALIA In this volume all 206 species of the family Solanaceae known to be indigenous or naturalised in Australia are described. The family includes important toxic plants, weeds and drug plants. The family Solanaceae in Australia contains 140 indigenous species such as boxthorn, wild tobacco, wild tomato, Pituri and tailflower. The 66 naturalised members include nightshade, tomato, thornapple, petunia, henbane, capsicum and Cape Gooseberry. There are keys for the identification of all genera and species. References are given for accepted names and synonyms. Maps are provided showing the distribution of nearly all species. Many are illustrated by line drawings or colour plates. Notes on habitat, variation and relationships are included. The volume is based on the most recent taxonomic research on the Solanaceae in Australia. Cover: Solanum semiarmatum F . Muell. Painting by Margaret Stones. Reproduced by courtesy of David Symon. Contents of volumes in the Flora of Australia, the faiimilies arranged according to the system of A.J. -

Kiwirrkurra IPA WA 2015, a Bush Blitz Survey Report

Kiwirrkurra Indigenous Protected Area Western Australia 6–18 September 2015 Bush Blitz Species Discovery Program Kiwirrkurra IPA, Western Australia 6–18 September 2015 What is Bush Blitz? Bush Blitz is a multi-million dollar partnership between the Australian Government, BHP Billiton Sustainable Communities and Earthwatch Australia to document plants and animals in selected properties across Australia. This innovative partnership harnesses the expertise of many of Australia’s top scientists from museums, herbaria, universities, and other institutions and organisations across the country. Abbreviations ABRS Australian Biological Resources Study ALA Atlas of Living Australia ANH Australian National Herbarium AVH Australia’s Virtual Herbarium CDNTS Central Desert Native Title Services DPaW Department of Parks and Wildlife DWS Desert Wildlife Services EDJTR Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport and Resources (Victoria) EPBC Act Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Commonwealth) IBRA Interim Biogeographic Regionalisation for Australia IPA Indigenous Protected Area NTH Northern Territory Herbarium Page 2 of 50 Kiwirrkurra IPA, Western Australia 6–18 September 2015 QM Queensland Museum UNSW University of New South Wales WAH Western Australian Herbarium WAM Western Australian Museum WCA Wildlife Conservation Act 1950 Page 3 of 50 Kiwirrkurra IPA, Western Australia 6–18 September 2015 Summary Kiwirrkurra Indigenous Protected Area (IPA) was the focus of a Bush Blitz expedition between 6 and 18 September 2015. This IPA is located in the tali (sandhill) country of the Gibson and Great Sandy deserts, in Western Australia (WA). The entire area is Kiwirrkurra Native Title Determination and is managed by Pintupi traditional owners with assistance from Central Desert Native Title Services (CDNTS). -

Flora and Vegetation Gap Analysis

Flora and Vegetation Survey Gap Analysis Woodie Woodie Mine Prepared By Prepared For MBS Environmental and Consolidated Minerals Date January 2020 DOCUMENT STATUS VERSION TYPE AUTHOR/S REVIEWER/S DATE DISTRIBUTED V1 Internal review E.M. Mattiske - - V2 Draft for client E.M. Mattiske E. Mattiske 17/12/2019 FINAL Final report L. Rowles/E. Mattiske E. Mattiske 15/01/2020 (ACN 063 507 175, ABN 39 063 507 175) PO Box 437 Kalamunda WA 6926 Phone: +61 8 9257 1625 Email: [email protected] COPYRIGHT AND DISCLAIMER Copyright The information contained in this report is the property of Mattiske Consulting Pty Ltd. The use or copying of the whole or any part of this report without the written permission of Mattiske Consulting Pty Ltd is not permitted. Disclaimer This report has been prepared on behalf of and for the exclusive use of MBS Environmental, and is subject to and issued in accordance with the agreement between MBS Environmental and Mattiske Consulting Pty Ltd. This report is based on the scope of services defined by MBS Environmental, the budgetary and time constraints imposed by MBS Environmental, and the methods consistent with the preceding. Mattiske Consulting Pty Ltd has utilised information and data supplied by MBS Environmental (and its agents), and sourced from government databases, literature, departments and agencies in the preparation of this report. Mattiske Consulting Pty Ltd has compiled this report on the basis that any supplied or sourced information and data was accurate at the time of publication. Mattiske Consulting Pty Ltd accepts no liability or responsibility whatsoever for the use of, or reliance upon, the whole or any part of this report by any third party. -

Alternative Approaches for Resolving the Phylogeny of Lamiaceae

OUT OF THE BUSHES AND INTO THE TREES: ALTERNATIVE APPROACHES FOR RESOLVING THE PHYLOGENY OF LAMIACEAE By GRANT THOMAS GODDEN A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2014 © 2014 Grant Thomas Godden To my father, Clesson Dale Godden Jr., who would have been proud to see me complete this journey, and to Mr. Tea and Skippyjon Jones, who sat patiently by my side and offered friendship along the way ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my deepest gratitude for the consistent support of my advisor, Dr. Pamela Soltis, whose generous allocation of time, innovative advice, encouragement, and mentorship positively shaped my research and professional development. I also offer my thanks to Dr. J. Gordon Burleigh, Dr. Bryan Drew, Dr. Ingrid Jordon-Thaden, Dr. Stephen Smith, and the members of my committee—Dr. Nicoletta Cellinese, Dr. Walter Judd, Dr. Matias Kirst, and Dr. Douglas Soltis—for their helpful advice, guidance, and research support. I also acknowledge the many individuals who helped make possible my field research activities in the United States and abroad. I wish to extend a special thank you to Dr. Angelica Cibrian Jaramillo, who kindly hosted me in her laboratory at the National Laboratory of Genomics for Biodiversity (Langebio) and helped me acquire collecting permits and resources in Mexico. Additional thanks belong to Francisco Mancilla Barboza, Gerardo Balandran, and Praxaedis (Adan) Sinaca for their field assistance in Northeastern Mexico; my collecting trip was a great success thanks to your resourcefulness and on-site support. -

Lamiaceae) Based on Chloroplast Ndhf and Nuclear ITS Sequence Data

CSIRO PUBLISHING www.publish.csiro.au/journals/asb Australian Systematic Botany, 22, 243–256 Infrageneric phylogeny of Chloantheae (Lamiaceae) based on chloroplast ndhF and nuclear ITS sequence data B. J. Conn A,D, N. Streiber A,B, E. A. Brown A, M. J. Henwood B and R. G. Olmstead C ANational Herbarium of New South Wales, Mrs Macquaries Road, Sydney, NSW 2000, Australia. BSchool of Biological Sciences, University of Sydney, NSW 2006, Australia. CDepartment of Biology, University of Washington, Box 355325, Seattle, WA 98195-1330, USA. DCorresponding author. Email: [email protected] Abstract. The tribe Chloantheae (Prostantheroideae, Lamiaceae) currently consists of over 100 species in nine genera, all of which are endemic to Australia. Generic delimitations were assessed using chloroplast 30ndhF and nuclear ITS nucleotide sequence data for up to seventy species. Analyses of the two datasets, independently and in combination, used maximum parsimony and Bayesian phylogenetic inference methods. Topologies derived from each marker were broadly congruent, but better resolution and stronger branch support was achieved by combining the datasets. The monophyly of the Chloantheae was confirmed. Brachysola is sister to the rest of the tribe and Chloanthes, Cyanostegia and Dicrastylis (including Mallophora) are monophyletic. Although the species within Dicrastylis were only partially resolved, it appears likely that the current sectional classification of this genus will require revision. A clade containing Newcastelia, Physopsis and Lachnostachys (=Physopsideae) was recovered, but the topology indicates that the current generic circumscriptions need further investigation. A close relationship between Hemiphora elderi, Pityrodia bartlingii and P. uncinata was resolved and reflects their palynological and carpological similarities. -

An Updated Tribal Classification of Lamiaceae Based on Plastome Phylogenomics Fei Zhao1†, Ya-Ping Chen1†, Yasaman Salmaki2, Bryan T

Zhao et al. BMC Biology (2021) 19:2 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12915-020-00931-z RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access An updated tribal classification of Lamiaceae based on plastome phylogenomics Fei Zhao1†, Ya-Ping Chen1†, Yasaman Salmaki2, Bryan T. Drew3, Trevor C. Wilson4, Anne-Cathrine Scheen5, Ferhat Celep6,7, Christian Bräuchler8, Mika Bendiksby9,10, Qiang Wang11, Dao-Zhang Min12, Hua Peng1, Richard G. Olmstead13,BoLi12* and Chun-Lei Xiang1* Abstract Background: A robust molecular phylogeny is fundamental for developing a stable classification and providing a solid framework to understand patterns of diversification, historical biogeography, and character evolution. As the sixth largest angiosperm family, Lamiaceae, or the mint family, consitutes a major source of aromatic oil, wood, ornamentals, and culinary and medicinal herbs, making it an exceptionally important group ecologically, ethnobotanically, and floristically. The lack of a reliable phylogenetic framework for this family has thus far hindered broad-scale biogeographic studies and our comprehension of diversification. Although significant progress has been made towards clarifying Lamiaceae relationships during the past three decades, the resolution of a phylogenetic backbone at the tribal level has remained one of the greatest challenges due to limited availability of genetic data. Results: We performed phylogenetic analyses of Lamiaceae to infer relationships at the tribal level using 79 protein-coding plastid genes from 175 accessions representing 170 taxa, 79 genera, and all 12 subfamilies. Both maximum likelihood and Bayesian analyses yielded a more robust phylogenetic hypothesis relative to previous studies and supported the monophyly of all 12 subfamilies, and a classification for 22 tribes, three of which are newly recognized in this study.