From Caroline Pratt and Helen Parkhurst to Lillian Weber And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Go Forth Unafraid

Go forth unafraid A Welcome to Dalton 2 Our Mission 4 Our History 5 The Dalton Plan 7 Our Focus on Values 9 The Dalton Technology Plan 12 The First Program 14 The Middle School 24 The High School 34 Our Faculty 48 Admissions Procedures and Financial Aid 56 Opportunities for Involvement 59 Welcome to The As both an alumna and The Dalton School played an important role in twentieth- century American educational history and continues to be the Head of School, I am a model emulated in schools around the world. Through the vision of its founder, Helen Parkhurst, Dalton is delighted that you are fortunate to have a unique and clearly articulated philosophy of learning that continues to guide the school’s interested in The Dalton educational practices today. True to our motto, Go Forth School. The purpose of Unafraid, we have fearlessly embraced the new challenges of educating students in the constantly changing world this catalog and the entire of the twenty-first century. While continuing to use Parkhurst’s philosophy as our basic framework, we admissions process is to regularly re-evaluate the knowledge and skills our students must possess in order to be enlightened, socially conscious, help you understand what and skilled young people. is distinctive about our Dalton is alive with a dedicated, highly trained faculty and an inquisitive and talented student body. A stimulating school so that you can curriculum and extensive service learning and extra- make an informed decision curricular opportunities continually expand Dalton students’ understanding of their world and empower in finding the optimal them as global citizens, a major goal of our school. -

Caroline Pratt: Progressive Pedagogy in Statu Nascendi

Occasional Paper Series Volume 2014 Number 32 Living a Philosophy of Early Childhood Education: A Festschrift for Harriet Article 6 Cuffaro October 2014 Caroline Pratt: Progressive Pedagogy In Statu Nascendi Jeroen Staring Bank Street College of Education Follow this and additional works at: https://educate.bankstreet.edu/occasional-paper-series Part of the Educational Methods Commons Recommended Citation Staring, J. (2014). Caroline Pratt: Progressive Pedagogy In Statu Nascendi. Occasional Paper Series, 2014 (32). Retrieved from https://educate.bankstreet.edu/occasional-paper-series/vol2014/iss32/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Educate. It has been accepted for inclusion in Occasional Paper Series by an authorized editor of Educate. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Caroline Pratt: Progressive Pedagogy In Statu Nascendi By Jeroen Staring This article explores two themes in the life of Caroline Pratt, founder of the Play School, later the City and Country School. These themes, central to Harriet Cuffaro’s values as a teacher and scholar, are Pratt’s early progressive pedagogy, developed during experimental shopwork between 1901 and 1908; and her theories on play and toys, developed while observing children play with her Do-With Toys and Unit Blocks between 1908 and 1914. Focusing on her early and previously unexplored writings, this article illustrates how Caroline Pratt developed a coherent theory of innovative progressive pedagogy. Figure 1 (left). Original drawing of Do-With doll, by Caroline Pratt. Figure 2 (right): Two wooden, jointed Do-With dolls. (Photo: Jeroen Staring, 2011; Courtesy City and Country School, New York City) 46 | Occasional Paper Series 32 bankstreet.edu/ops Caroline Pratt’s Education In 1884, Caroline Louise Pratt, age 17, had her first teaching experience at the summer session of a school near her hometown, Fayetteville, New York. -

Progressive Education

PROGRESSIVE EDUCATION Lessons fronn the Past and Present Susan F. Semel, Alan R. Sadovnik, and Ryan W. Coughlan Progressive education is one of the most enduring educational reform move ments in this country, with a lifespan of over one hundred years. Although as noted earlier, it waxes and wanes in popularity, many of its practices now appear so regularly in both private and public schools as to have become almost mainstream. But from the schools that were the pioneers, what useful ■ lessons can we learn? The histories of the early progressive schools profiled in ■part 1 illustrate what happened to some of the progressive schools founded in I jhe first part of the twentieth century. But even now, they serve as important reminders for educators concerned with the competing issues of stability and change in schools with particular progressive philosophies—reminders, spe cifically, of the complex nature of school reform.' As we have seen in these histories, balancing the original intentions of progressive founders with the known demands upon practitioners has been the challenge some of the schools have met successfully and others have not. As contemporary American educators consider the school choice movement, the burgeoning expansion of charter schools, and the growing focus on stan- dards-based testing and accountability measures, they would do well to look back for guidance at some of the original schools representative of the “new education.” Particularly instructive. The Dalton School and The City and 374 SUSAN F. SEMEL ET AL. Country School are both urban independent schools that have enjoyed strong and enduring leaders, well-articulated philosophies and accompanying ped agogic practice, and a neighborhood to supply its clientele. -

Early Steps Celebration 30Th Anniversary Thursday, May 18, 2017 the University Club New York, NY

Benefit Early Steps Celebration 30th Anniversary Thursday, May 18, 2017 The University Club New York, NY Early Steps 540 East 76th Street • New York, NY 10021 www.earlysteps.org • 212.288.9684 Horace Mann School and all of our Early Steps students and families, past and present, join in celebrating Early Steps’ 30 Years as A Voice for Diversity in NYC Independent Schools Letter from our Director Dear Friends, For nearly three decades, it has been my joy and re- sponsibility to guide the parents of children of color through the process of applying to New York City in- dependent schools for kindergarten and first grade, helping them to realize their hopes and dreams for their children. While over 3,500 students of color entered school with the guidance of Early Steps, it is humbling to know that the impact has been so much greater. We hear time and © 2012 Victoria Jackson Photography again how families, schools and lives have been trans- formed as a result of the doors of opportunity that were opened with the help of Early Steps. Doors where academic excellence is the norm and children learn and play with others whose life’s experiences are not the same as theirs, benefitting all children. We are proud of our 30-year partnership with now over 50 New York City independent schools who nurture, educate and challenge our children to be the best that they can be. They couldn’t be in better hands! Tonight we honor four Early Steps alumni. These accomplished young adults all benefited from the wisdom of their parents who knew the importance of providing their children with the best possible education beginning in Kindergarten. -

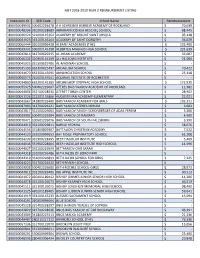

MST 2018-2019 Year 2 Reimbursement Listing

MST 2018-2019 YEAR 2 REIMBURSMENT LISTING Institution ID SED Code School Name Reimbursement 800000039032 500402226478 A H SCHREIBER HEBREW ACADEMY OF ROCKLAND $ 70,039 800000048206 310200228689 ABRAHAM JOSHUA HESCHEL SCHOOL $ 68,445 800000046124 321000145364 ACADEMY OF MOUNT SAINT URSULA $ 95,148 800000041923 353100145263 ACADEMY OF SAINT DOROTHY $ 36,029 800000060444 010100996428 ALBANY ACADEMIES (THE) $ 102,490 800000039341 500101145198 ALBERTUS MAGNUS HIGH SCHOOL $ 231,639 800000042814 342700629235 AL-IHSAN ACADEMY $ 33,087 800000046332 320900145199 ALL HALLOWS INSTITUTE $ 21,084 800000045025 331500629786 AL-MADINAH SCHOOL $ - 800000035193 662300625497 ANDALUSIA SCHOOL $ 70,422 800000034670 662300145095 ANNUNCIATION SCHOOL $ 25,148 800000050573 261600167041 AQUINAS INSTITUTE OF ROCHESTER $ - 800000034860 662200145185 ARCHBISHOP STEPINAC HIGH SCHOOL $ 172,930 800000055925 500402229697 ATERES BAIS YAAKOV ACADEMY OF ROCKLAND $ 12,382 800000044056 332100228530 ATERET TORAH CENTER $ 28,962 800000051126 222201155866 AUGUSTINIAN ACADEMY-ELEMENTARY $ 22,021 800000042667 342800226480 BAIS YAAKOV ACADEMY FOR GIRLS $ 103,321 800000087003 342700226221 BAIS YAAKOV ATERES MIRIAM $ 3,683 800000043817 331500229003 BAIS YAAKOV FAIGEH SCHONBERGER OF ADAS YEREIM $ 5,306 800000039002 500401229384 BAIS YAAKOV OF RAMAPO $ 4,980 800000070471 590501226076 BAIS YAAKOV OF SOUTH FALLSBURG $ 3,390 800000044016 332100229811 BARKAI YESHIVA $ 58,076 800000044556 331800809307 BATTALION CHRISTIAN ACADEMY $ 7,522 800000044120 332000999653 BAY RIDGE PREPARATORY SCHOOL -

Access, Equity and Activism: TEACHING the POSSIBLE! Progressivenational Education Conference Network New York City October 8-10, 2015

1 Access, Equity and Activism: TEACHING THE POSSIBLE! Progressive Education Network National Conference New York City PEN_Conference_2015.indd 1 October 8-10, 2015 9/29/15 2:25 PM 2 Mission and History of the Progressive Education Network “The Progressive Education Network exists to herald and promote the vision of progressive education on a national basis, while providing opportunities for educators to connect, support, and learn from one another.” In 2004 and 2005, The School in Rose Valley, PA, celebrated its seventy- fifth anniversary by hosting a two-part national conference, Progressive Education in the 21st Century. Near the end of the conference, a group of seven educators from public and private schools around the country rallied to a call-to-action to revive the Network of Progressive Educators, which had been inactive since the early 1990s. Inspired by the progressive tenets of the conference, the group shared a grand collective mission: to establish a national group to rise up, protect, clarify, and celebrate the principles of progressive education and to fashion a revitalized national educational vision. This group, “The PEN Seven” (Maureen Cheever, Katy Dalgleish, Tom Little, Kate (McLellan) Blaker, John Pecore, Lisa Shapiro, and Terry Strand) hosted the organization’s first national conference in San Francisco in 2007. As a result of the committee’s efforts, the Progressive Education Network (PEN) was formed and in 2009 was incorporated as a 501 (c) 3 charitable, non-profit organization. Biannual conferences, supported by PEN and produced by various committees, followed in DC, Chicago, and LA, with attendance growing from 250 to 950. -

The Bank Street Developmental Interaction Approach in Liliana's Kindergarten Classroom

Bank Street College of Education Educate Books 2015 Learning to Play, Playing to Learn: The Bank Street Developmental Interaction Approach in Liliana's Kindergarten Classroom Soyoung Park Stanford University, [email protected] Ira Lit Stanford University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://educate.bankstreet.edu/books Part of the Curriculum and Instruction Commons, Early Childhood Education Commons, and the Social and Philosophical Foundations of Education Commons Recommended Citation Park, S., & Lit, I. (2015). Learning to Play, Playing to Learn: The Bank Street Developmental Interaction Approach in Liliana's Kindergarten Classroom. Retrieved from https://educate.bankstreet.edu/books/15 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by Educate. It has been accepted for inclusion in Books by an authorized administrator of Educate. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Stanford Center for Opportunity Policy in Education Teaching for a Changing World: The Graduates of Bank Street College of Education Learning to Play, Playing to Learn: The Bank Street Developmental-Interaction Approach in Liliana’s Kindergarten Classroom By Soyoung Park and Ira Lit sco e Stanford Center for Opportunity Policy in Education This case study is one of five publications from the larger study entitled Teaching for a Changing World: The Graduates of Bank Street College of Education Linda Darling-Hammond and Ira Lit, principal investigators About the authors: Soyoung Park, doctoral student, Stanford Graduate School of Education Ira Lit, PhD, associate professor of Education (Teaching), Stanford Graduate School of Education, and faculty director, Stanford Elementary Teacher Education Program (STEP Elementary) Suggested citation: Park, S. -

Maquetación 1

The Dalton Plan in Spain: Reception and Appropriation (1920-1939)1 El Plan Dalton en España: Recepción y Apropiación (1920-1939) DOI: 10.4438/1988-592X-RE-2017-377-355 María del Mar Del Pozo Andrés Universidad de Alcalá Sjaak Braster Erasmus University of Rotterdam Abstract Introduction. All the methodologies developed by the Progressive Education movement followed a comparable process of reception and appropriation in Spain. This process began with visits abroad by «pedagogical explorers», sponsored for the most part by the Junta para Ampliación de Estudios (Board for Advanced Studies) and concluded with the practical experiences performed by the Spanish schoolteachers in their schools. This paper explores how the Dalton Plan perfectly matches the model constructed for explaining other innovative methodologies, but also tries to understand the reasons of its little success amongst the teachers. Methodology. All the steps of the historical method have been followed: research and review of manuscript, bibliographical, hemerographical and iconographical sources, comparison between countries and critical analysis of the documentation that was used. Results. In this article we begin by showing the considerable impact that the Dalton Plan had countries such as Great Britain, that were in search of a good alternative for the (1) This work forms part of the project «Educational Progressivism and School Tradition in Spain through Photography (1900–1970)» [EDU2014-52498-C2-1-P], funded by the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness within the framework of the National R&D and Innovation Plan. Revista de Educación, 377. July-September 2017, pp. 111-134 111 Received: 02-11-2016 Accepted: 24-03-2017 Del Pozo Andrés, M.ª del M., Braster, S. -

ISAAGNY Member Schools 2020-21 Independent School Admissions Association of Greater New York

ISAAGNY Member Schools 2020-21 Independent School Admissions Association of Greater New York 14th Street Y Preschool Montclare Children’s School The Convent of the Sacred Heart School of New 92nd Street YM-YWHA Nursery School Morningside Montessori School York A Town House International School Nursery School of Habonim The Dalton School Alexander Robertson School Park Avenue Methodist Day School The Elisabeth Morrow School All Souls School Park Avenue Synagogue Penn Family Early The Episcopal School in the City of New York Bank Street School for Children Childhood Center The Family Annex Barrow Street Nursery School Park Children’s Day School The Family School / Family School West Basic Trust Infant and Toddler Center Poly Prep Country Day School The First Presbyterian Church in the City of Beginnings Nursery School Professional Children’s School New York / First Presbyterian Church Birch Wathen Lenox Purple Circle Day Care Inc. Nursery School Broadway Presbyterian Church Nursery School Rabbi Arthur Schneier Park East Day School The Gateway School Blue School Red Balloon Daycare Center Inc. The Harvey School Brooklyn Friends School Resurrection Episcopal Day School The Hewitt School Brooklyn Heights Montessori School Riverdale Country School The IDEAL School of Manhattan Brotherhood Synagogue Nursery School Rodeph Sholom School The International Preschools Central Synagogue May Family Nursery School Roosevelt Island Day Nursery The Kew-Forest School, Inc. Chelsea Day School Rudolf Steiner School The Madison Avenue Presbyterian Church Children’s All Day School Saint Ann’s School Day School Christ Church Day School Saint David’s School The Masters School City and Country School Seton Day Care Medical Center Nursery School Collegiate School St. -

Katharine Taylor and the Shady Hill School, 1915-1949

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-1989 Katharine Taylor and the Shady Hill School, 1915-1949. Sandra Ramsey Loehr University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Loehr, Sandra Ramsey, "Katharine Taylor and the Shady Hill School, 1915-1949." (1989). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 4460. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/4460 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. KATHARINE TAYLOR AND THE SHADY HILL SCHOOL, 1915-1949 A Dissertation Presented by SANDRA RAMSEY LOEHR Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF EDUCATION September 1989 Education Q Copyright by Sandra Ramsey Loehr 1989 All Rights Reserved KATHARINE TAYLOR AND THE SHADY HILL SCHOOL, 1915-1949 A Dissertation Presented By SANDRA RAMSEY LOEHR Approved as to style and content by: /L. yce(/A. Berkman, Member Marilyn'Tlaring-Hidore, Dean School of Education ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express by appreciation to the following individuals for their continuing encouragement and support throughout this project: Hank Loehr, David Loehr, Philip Eddy, Carolyn Edwards, Joyce Berkman, William Kornegay, Myrtle Orloff, Marcia Stefan, and Fred W. Ramsey. iv ABSTRACT KATHARINE TAYLOR AND THE SHADY HILL SCHOOL, 1915-1949 SEPTEMBER 1989 SANDRA RAMSEY LOEHR, B.S., OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY Ed.M., HARVARD UNIVERSITY Ed.D., UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS Directed by: Professor S. -

New York Metro Area Member Day Schools

New York Metro Area Member Day Schools A.C.T. Early Childhood Program at The Cathedral of Children’s All Day School and Pre-Nursery St. John the Divine Christ Church Day School Aaron School The Church of the Epiphany Day School The Abraham Joshua Heschel School The Churchill School and Center Academy of St. Joseph City and Country School The Acorn School Collegiate School Alexander Robertson School Columbia Grammar and Preparatory School All Saints Episcopal Day School Columbia Greenhouse Nursery School All Souls School Columbus Pre-School The Allen-Stevenson School Congregation Beth Elohim Early Childhood Center Avenues: The World School Corlears School Bank Street School for Children The Dalton School Barrow Street Nursery School The Day School at Christ & Saint Stephen’s Basic Trust Dillon Child Study Center at St. Joseph’s College Battery Park Montessori The Downtown Little School Battery Park City Day Nursery Dutchess Day School Bay Ridge Preparatory School Dwight School Beansprouts Nursery School Dwight-Englewood School New York York 10028 New York New East 82nd Street 115 The Beeekman School (& The Tutoring School) Eagle Hill School (Greenwich, CT) Beginnings Nursery School East Woods School The Berkeley Carroll School The École The Birch Wathen Lenox School Educational Alliance Preschool at the Manny Blue School Cantor Center The Brearley School The Elisabeth Morrow School The Brick Church School The Episcopal School in the City of New York The British International School of New York Ethical Culture Fieldston School Broadway -

NYSAIS Accreditation Volunteers 2016 - 2017

NYSAIS Accreditation Volunteers 2016 - 2017 NYSAIS would like to thank the following 211 volunteers for their exceptional work on accreditation visiting teams during the past year. Chair Concepcion Alvar Marymount School of New York Bart Baldwin St. Luke's School Peter Becker The Gunnery Alan Bernstein Lawrence Woodmere Academy Susan Braun The Waldorf School of Garden City Paul Burke The Nightingale-Bamford School Drew Casertano Millbrook School Marcie Craig Post International Reading Association Jody Douglass Buffalo Seminary - Retired James Dunaway Manlius Pebble Hill School Anthony Featherston The Town School Maureen Fonseca Sports and Arts in Schools Foundation Darryl Ford William Penn Charter School Linda Gibbs Hewitt School - Retired Bradford Gioia Montgomery Bell Academy David Hochschartner North Country School Josie Holford Poughkeepsie Day School - Retired Jean-Marc Juhel Buckley Country Day School Susan Kambrich Woodland Hill Montessori School Christopher Lauricella The Park School of Buffalo Lee Levison Collegiate School Richard Marotta Garden School Ann Mellow National Association of Episcopal Schools Marsha Nelson The Cathedral School Michael O'Donoghue Holy Child Academy Patricia Pell Madison Avenue Presbyterian Church Day School - Retired Dane Peters Brooklyn Heights Montessori School - Retired Scott Reisinger Trevor Day School NYSAIS Accreditation Volunteers 2016 - 2017 Rebecca Skinner The International School of Brooklyn Meg Taylor Robert C. Parker School Kate Turley City and Country School Robert Vitalo The Berkeley Carroll School Stephen Watters The Green Vale School - Retired Larry Weiss Brooklyn Friends School Finance Laila Marie AlAskari The Brick Church School Angela Artale Staten Island Academy Diane Beckman Dominican Academy Marc Bogursky Blue School Joan Dannenberg Trinity School Nancy Diekmann Manhattan Country School Steven Dudley Trevor Day School Susan Evans Woodland Hill Montessori School Richard Fleck Portledge School Theresa Foy Buckley Country Day School Gina Fuller Millbrook School Peter Ganzenmuller St.