The Threads They Follow: Bank Street Teachers in a Changing World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Southwest Bronx (SWBX): a Map Is Attached, Noting Recent Development

REDC REGION / MUNICIPALITY: New York City - Borough of Bronx DOWNTOWN NAME: Southwest Bronx (SWBX): A map is attached, noting recent development. The boundaries proposed are as follows: • North: Cross Bronx Expressway • South: East River • East: St Ann’s Avenue into East-Third Avenue • West: Harlem River APPLICANT NAME & TITLE: Regional Plan Association (RPA), Tom Wright, CEO & President. See below for additional contacts. CONTACT EMAILS: Anne Troy, Manager Grants Relations: [email protected] Melissa Kaplan-Macey, Vice President, State Programs, [email protected] Tom Wright, CEO & President: [email protected] REGIONAL PLAN ASSOCIATION - BRIEF BACKGROUND: Regional Plan Association (RPA) was established as a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization in 1929 and for nearly a century has been a key planner and player in advancing long-range region-wide master plans across the tri-state. Projects over the years include the building of the the Battery Tunnel, Verrazano Bridge, the location of the George Washington Bridge, the Second Avenue subway, the New Amtrak hub at Moynihan Station, and Hudson Yards, and establishing a city planning commission for New York City. In November 2017, RPA published its Fourth Regional Plan for the tri-state area, which included recommendations for supporting and expanding community-centered arts and culture in New York City neighborhoods to leverage existing creative and cultural diversity as a driver of local economic development. The tri-state region is a global leader in creativity. Its world-class art institutions are essential to the region’s identity and vitality, and drive major economic benefits. Yet creativity on the neighborhood level is often overlooked and receives less support. -

Caroline Pratt: Progressive Pedagogy in Statu Nascendi

Occasional Paper Series Volume 2014 Number 32 Living a Philosophy of Early Childhood Education: A Festschrift for Harriet Article 6 Cuffaro October 2014 Caroline Pratt: Progressive Pedagogy In Statu Nascendi Jeroen Staring Bank Street College of Education Follow this and additional works at: https://educate.bankstreet.edu/occasional-paper-series Part of the Educational Methods Commons Recommended Citation Staring, J. (2014). Caroline Pratt: Progressive Pedagogy In Statu Nascendi. Occasional Paper Series, 2014 (32). Retrieved from https://educate.bankstreet.edu/occasional-paper-series/vol2014/iss32/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Educate. It has been accepted for inclusion in Occasional Paper Series by an authorized editor of Educate. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Caroline Pratt: Progressive Pedagogy In Statu Nascendi By Jeroen Staring This article explores two themes in the life of Caroline Pratt, founder of the Play School, later the City and Country School. These themes, central to Harriet Cuffaro’s values as a teacher and scholar, are Pratt’s early progressive pedagogy, developed during experimental shopwork between 1901 and 1908; and her theories on play and toys, developed while observing children play with her Do-With Toys and Unit Blocks between 1908 and 1914. Focusing on her early and previously unexplored writings, this article illustrates how Caroline Pratt developed a coherent theory of innovative progressive pedagogy. Figure 1 (left). Original drawing of Do-With doll, by Caroline Pratt. Figure 2 (right): Two wooden, jointed Do-With dolls. (Photo: Jeroen Staring, 2011; Courtesy City and Country School, New York City) 46 | Occasional Paper Series 32 bankstreet.edu/ops Caroline Pratt’s Education In 1884, Caroline Louise Pratt, age 17, had her first teaching experience at the summer session of a school near her hometown, Fayetteville, New York. -

Queering Education: Pedagogy, Curriculum, Policy

Occasional Paper Series Volume 2017 Number 37 Queering Education: Pedagogy, Article 10 Curriculum, Policy May 2017 Queering Education: Pedagogy, Curriculum, Policy Follow this and additional works at: https://educate.bankstreet.edu/occasional-paper-series Part of the Curriculum and Social Inquiry Commons, Disability and Equity in Education Commons, Educational Assessment, Evaluation, and Research Commons, Educational Sociology Commons, Education Policy Commons, Gender and Sexuality Commons, Politics and Social Change Commons, Social and Philosophical Foundations of Education Commons, and the Social Policy Commons Recommended Citation (2017). Queering Education: Pedagogy, Curriculum, Policy. Occasional Paper Series, 2017 (37). Retrieved from https://educate.bankstreet.edu/occasional-paper-series/vol2017/iss37/10 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by Educate. It has been accepted for inclusion in Occasional Paper Series by an authorized editor of Educate. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Queering Education: Pedagogy, Curriculum, Policy Introduction Guest Editor: Darla Linville Essays by Denise Snyder Cammie Kim Lin Ashley Lauren Sullivan and Laurie Lynne Urraro Clio Stearns Joseph D. Sweet and David Lee Carlson Julia Sinclair-Palm Stephanie Shelton benjamin lee hicks 7 1 s e 0 i 2 r e S r e p April a P l a n io s a 7 c c 3 O Occasional Paper Series | 1 Table of Contents Introduction ...................................................................................................................................................... -

OTTAWA ONTARIO Accelerating Success

#724 BANK STREET OTTAWA ONTARIO Accelerating success. 724 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 INVESTMENT HIGHLIGHTS 6 PROPERTY OVERVIEW 8 AREA OVERVIEW 10 FUTURE DEVELOPMENTS 14 CONTENTS ZONING 16 724 THE PROPERTY OFFERS DIRECT POSITIONING WITHIN THE CENTRE OF OTTAWA’S COVETED GLEBE NEIGHBOURHOOD EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 724 Bank Street offers both potential investors and owner- Key Highlights occupiers an opportunity to acquire a character asset within • Rarely available end unit character asset within The Glebe Ottawa’s much desired Glebe neighbourhood. • Attractive unique facade with signage opportunity At approximately 8,499 SF in size, set across a 3,488 SF lot, this • Flagship retail opportunity at grade 1945 building features two storeys for potential office space and • Excellent locational access characteristics, just steps from OC / or retail space. 5,340 SF is above grade, 3,159 SF SF is below transpo and minutes from Highway 417 grade (As per MPAC). • Strong performing surrounding retail market with numerous local and national occupiers Located on Bank Street at First Avenue, approximately 600 • Attractive to future office or retail users, private investors and meters north of the Lansdowne, the Property is encompassed by surrounding landholders character commercial office space, a supportive residential and • Excellent corner exposure condominium market and a destination retail and dining scene in Ottawa. ASKING PRICE: $3,399,000 724 BANK STREET 5 INVESTMENT HIGHLIGHTS A THRIVING URBAN NODE OFFERING TRENDY SHOPPING, DINING AND LIVING IN OTTAWA, THE PROPERTY IS SURROUNDED BY AN ECLECTIC MIX OF RETAILERS, RESTAURANTS AND COFFEE SHOPS. The Property presents an opportunity for an An end-unit asset, complete with both First Avenue and Drawn to The Glebe by its notable retail and dining scene, investor or owner-occupier to acquire a rarely available, Bank Street frontage, the Property presents an exceptional commercial rents within the area have continued to rise character asset in The Glebe neighbourhood of Ottawa. -

Progressive Education

PROGRESSIVE EDUCATION Lessons fronn the Past and Present Susan F. Semel, Alan R. Sadovnik, and Ryan W. Coughlan Progressive education is one of the most enduring educational reform move ments in this country, with a lifespan of over one hundred years. Although as noted earlier, it waxes and wanes in popularity, many of its practices now appear so regularly in both private and public schools as to have become almost mainstream. But from the schools that were the pioneers, what useful ■ lessons can we learn? The histories of the early progressive schools profiled in ■part 1 illustrate what happened to some of the progressive schools founded in I jhe first part of the twentieth century. But even now, they serve as important reminders for educators concerned with the competing issues of stability and change in schools with particular progressive philosophies—reminders, spe cifically, of the complex nature of school reform.' As we have seen in these histories, balancing the original intentions of progressive founders with the known demands upon practitioners has been the challenge some of the schools have met successfully and others have not. As contemporary American educators consider the school choice movement, the burgeoning expansion of charter schools, and the growing focus on stan- dards-based testing and accountability measures, they would do well to look back for guidance at some of the original schools representative of the “new education.” Particularly instructive. The Dalton School and The City and 374 SUSAN F. SEMEL ET AL. Country School are both urban independent schools that have enjoyed strong and enduring leaders, well-articulated philosophies and accompanying ped agogic practice, and a neighborhood to supply its clientele. -

Early Steps Celebration 30Th Anniversary Thursday, May 18, 2017 the University Club New York, NY

Benefit Early Steps Celebration 30th Anniversary Thursday, May 18, 2017 The University Club New York, NY Early Steps 540 East 76th Street • New York, NY 10021 www.earlysteps.org • 212.288.9684 Horace Mann School and all of our Early Steps students and families, past and present, join in celebrating Early Steps’ 30 Years as A Voice for Diversity in NYC Independent Schools Letter from our Director Dear Friends, For nearly three decades, it has been my joy and re- sponsibility to guide the parents of children of color through the process of applying to New York City in- dependent schools for kindergarten and first grade, helping them to realize their hopes and dreams for their children. While over 3,500 students of color entered school with the guidance of Early Steps, it is humbling to know that the impact has been so much greater. We hear time and © 2012 Victoria Jackson Photography again how families, schools and lives have been trans- formed as a result of the doors of opportunity that were opened with the help of Early Steps. Doors where academic excellence is the norm and children learn and play with others whose life’s experiences are not the same as theirs, benefitting all children. We are proud of our 30-year partnership with now over 50 New York City independent schools who nurture, educate and challenge our children to be the best that they can be. They couldn’t be in better hands! Tonight we honor four Early Steps alumni. These accomplished young adults all benefited from the wisdom of their parents who knew the importance of providing their children with the best possible education beginning in Kindergarten. -

Vol;Pxciii.-No. 28. S Nor Walk, Conn., Friday, July 14

An Entertaining and Instmctive Home Jojirhal, Especially Devoted to Local News and Interests, [$1.00 a Year. Founded in 1800.] 15 ' T j/St3jCQQ PRICE TWO CENTS: ci|- 14?; Ib93. VOL;PXCIII.-NO. 28. S NOR WALK, CONN., FRIDAY, JULY gSs I. O. O. F. Installation. ||| Dislocated His Shoulder. * Pay Your Taxes. ^ ^J't Rev. S. H. Watkins, rector of Grace - iK, A new mast was placed in the yacht The following officers of Kabarisa* Site / :\i I Our Elms Doomed. TERSE TALES OF THE TIMES. Ernie, this morning, to replace the one After to-morrow, July 15th, nine per Church, is in receipt of a letter advis cent penalty will be added to all unpaid Encampment, I. O. O. F., were install - ... - It seems to be an undoubted fact broken last Sunday. Commodore Bowe ing him that Mr. Henry A. Hills, or r Borough Taxes. ..„ ed last evening, by a Deputy from ganist of the church, had onMonday tliat our splendid elms, the glory of the ''"A new hydrant has been placed on superintended the work. • - ;x East avenue near the Selleck school. Stamford: Frederick Andrews, C. P.; dislocated his shoulder, at Williains- New England summer-time, are doom S. B. Wllspn, S. W.; R. Mitchell, J. port, Pa., where in company with his ife ir. t The contract for putting the cross HI Saloons Raided. W.; St. John Merrill, S.; B. S. Keith, ed to destruction. The continued an 5'>:'Mr. Edgar N. Sloan has sold his Sheriff Cole raided three unlicensed wife he is visiting friends. As to how walks, along the line of the tramway in T.; John Kenney, H. -

MST 2018-2019 Year 2 Reimbursement Listing

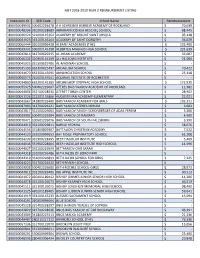

MST 2018-2019 YEAR 2 REIMBURSMENT LISTING Institution ID SED Code School Name Reimbursement 800000039032 500402226478 A H SCHREIBER HEBREW ACADEMY OF ROCKLAND $ 70,039 800000048206 310200228689 ABRAHAM JOSHUA HESCHEL SCHOOL $ 68,445 800000046124 321000145364 ACADEMY OF MOUNT SAINT URSULA $ 95,148 800000041923 353100145263 ACADEMY OF SAINT DOROTHY $ 36,029 800000060444 010100996428 ALBANY ACADEMIES (THE) $ 102,490 800000039341 500101145198 ALBERTUS MAGNUS HIGH SCHOOL $ 231,639 800000042814 342700629235 AL-IHSAN ACADEMY $ 33,087 800000046332 320900145199 ALL HALLOWS INSTITUTE $ 21,084 800000045025 331500629786 AL-MADINAH SCHOOL $ - 800000035193 662300625497 ANDALUSIA SCHOOL $ 70,422 800000034670 662300145095 ANNUNCIATION SCHOOL $ 25,148 800000050573 261600167041 AQUINAS INSTITUTE OF ROCHESTER $ - 800000034860 662200145185 ARCHBISHOP STEPINAC HIGH SCHOOL $ 172,930 800000055925 500402229697 ATERES BAIS YAAKOV ACADEMY OF ROCKLAND $ 12,382 800000044056 332100228530 ATERET TORAH CENTER $ 28,962 800000051126 222201155866 AUGUSTINIAN ACADEMY-ELEMENTARY $ 22,021 800000042667 342800226480 BAIS YAAKOV ACADEMY FOR GIRLS $ 103,321 800000087003 342700226221 BAIS YAAKOV ATERES MIRIAM $ 3,683 800000043817 331500229003 BAIS YAAKOV FAIGEH SCHONBERGER OF ADAS YEREIM $ 5,306 800000039002 500401229384 BAIS YAAKOV OF RAMAPO $ 4,980 800000070471 590501226076 BAIS YAAKOV OF SOUTH FALLSBURG $ 3,390 800000044016 332100229811 BARKAI YESHIVA $ 58,076 800000044556 331800809307 BATTALION CHRISTIAN ACADEMY $ 7,522 800000044120 332000999653 BAY RIDGE PREPARATORY SCHOOL -

Pgs. 1-44 AUG 08 .Indd

August 15, 2008 Vol. 38 No. 7 Serving the Glebe community since 1973 FREE PHOTO: GIOVANNI Max Keeping dances with onlookers in 2006 Dance down Bank Street on Saturday, August 23 BY JUNE CREELMAN will feature great music, and there will be children’s activities, a skateboard Get out your dancing shoes for the Ottawa Regional Cancer Foundation’s competition, a cooking competition, outdoor patios and special promotions by third annual Dancing in the Streets on Sat., Aug. 23. Join Honourary Chair, Bank Street businesses. Don’t miss the opening ceremonies at 2 p.m., with the Max Keeping as Bank Street is closed to traffic between Glebe and Fifth av- Ottawa Firefighters band and special guests. enues – to salute those who, like Max, have lived – and are still living through Activities start at noon, but Bank Street from Glebe to Fifth will be closed the cancer journey. The Ottawa Regional Cancer Foundation is committed to all day. Plan ahead to avoid frustration and watch for special event parking increasing and celebrating survivorship by raising funds and awareness to sup- restrictions. It’s the one day a year when Bank Street is free of cars, so stay in port cancer care programs. the neighbourhood and enjoy your main street. It’s all for a great cause! This year’s Dancing in the Street features more dancing than ever before. Dancing in the Streets is sponsored by the Ottawa Citizen, the Government There will be a dance competition, dance performances, dance lessons and of Ontario, McKeen Loeb Glebe, the Glebe Business Improvement Area, Sco- dance parties all along Bank Street. -

A CULTURAL HERITAGE IMPACT STATEMENT 667 Bank Street, Ottawa, Ontario

A CULTURAL HERITAGE IMPACT STATEMENT 667 Bank Street, Ottawa, Ontario SUBMITTED TO: Vincent P. Colizza Architect Inc. PREPARED BY: COMMONWEALTH RESOURCE MANAGEMENT May 2016 A Cultural Heritage Impact Statement - 667 Bank Street, Ottawa May 2016 Image Cover Page: Vincent P. Colizza Architect Inc. Dated January 20, 2016 Commonwealth Resource Management 1 A Cultural Heritage Impact Statement - 667 Bank Street, Ottawa May 2016 Table of Contents A CULTURAL HERITAGE IMPACT STATEMENT 667 Bank Street, Ottawa, Ontario ........................................ 0 1.0 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................... 4 1.1 Introduction ......................................................................................................................................... 4 1.2 Present Owner and Contact Information ...................................................................................... 4 1.3 Site Location, Current Conditions and Introduction to Development Site ................................... 4 1.4 Concise Description of Context ..................................................................................................... 6 1.5 Built Heritage Context and Street Characteristics (Neighbourhood Character) ........................... 7 1.6 Relevant Information from Council Approved Documents ........................................................... 8 1.7 Digital Images of Cultural Heritage Attributes ............................................................................. -

Access, Equity and Activism: TEACHING the POSSIBLE! Progressivenational Education Conference Network New York City October 8-10, 2015

1 Access, Equity and Activism: TEACHING THE POSSIBLE! Progressive Education Network National Conference New York City PEN_Conference_2015.indd 1 October 8-10, 2015 9/29/15 2:25 PM 2 Mission and History of the Progressive Education Network “The Progressive Education Network exists to herald and promote the vision of progressive education on a national basis, while providing opportunities for educators to connect, support, and learn from one another.” In 2004 and 2005, The School in Rose Valley, PA, celebrated its seventy- fifth anniversary by hosting a two-part national conference, Progressive Education in the 21st Century. Near the end of the conference, a group of seven educators from public and private schools around the country rallied to a call-to-action to revive the Network of Progressive Educators, which had been inactive since the early 1990s. Inspired by the progressive tenets of the conference, the group shared a grand collective mission: to establish a national group to rise up, protect, clarify, and celebrate the principles of progressive education and to fashion a revitalized national educational vision. This group, “The PEN Seven” (Maureen Cheever, Katy Dalgleish, Tom Little, Kate (McLellan) Blaker, John Pecore, Lisa Shapiro, and Terry Strand) hosted the organization’s first national conference in San Francisco in 2007. As a result of the committee’s efforts, the Progressive Education Network (PEN) was formed and in 2009 was incorporated as a 501 (c) 3 charitable, non-profit organization. Biannual conferences, supported by PEN and produced by various committees, followed in DC, Chicago, and LA, with attendance growing from 250 to 950. -

The Bank Street Developmental Interaction Approach in Liliana's Kindergarten Classroom

Bank Street College of Education Educate Books 2015 Learning to Play, Playing to Learn: The Bank Street Developmental Interaction Approach in Liliana's Kindergarten Classroom Soyoung Park Stanford University, [email protected] Ira Lit Stanford University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://educate.bankstreet.edu/books Part of the Curriculum and Instruction Commons, Early Childhood Education Commons, and the Social and Philosophical Foundations of Education Commons Recommended Citation Park, S., & Lit, I. (2015). Learning to Play, Playing to Learn: The Bank Street Developmental Interaction Approach in Liliana's Kindergarten Classroom. Retrieved from https://educate.bankstreet.edu/books/15 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by Educate. It has been accepted for inclusion in Books by an authorized administrator of Educate. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Stanford Center for Opportunity Policy in Education Teaching for a Changing World: The Graduates of Bank Street College of Education Learning to Play, Playing to Learn: The Bank Street Developmental-Interaction Approach in Liliana’s Kindergarten Classroom By Soyoung Park and Ira Lit sco e Stanford Center for Opportunity Policy in Education This case study is one of five publications from the larger study entitled Teaching for a Changing World: The Graduates of Bank Street College of Education Linda Darling-Hammond and Ira Lit, principal investigators About the authors: Soyoung Park, doctoral student, Stanford Graduate School of Education Ira Lit, PhD, associate professor of Education (Teaching), Stanford Graduate School of Education, and faculty director, Stanford Elementary Teacher Education Program (STEP Elementary) Suggested citation: Park, S.