Katharine Taylor and the Shady Hill School, 1915-1949

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Caroline Pratt: Progressive Pedagogy in Statu Nascendi

Occasional Paper Series Volume 2014 Number 32 Living a Philosophy of Early Childhood Education: A Festschrift for Harriet Article 6 Cuffaro October 2014 Caroline Pratt: Progressive Pedagogy In Statu Nascendi Jeroen Staring Bank Street College of Education Follow this and additional works at: https://educate.bankstreet.edu/occasional-paper-series Part of the Educational Methods Commons Recommended Citation Staring, J. (2014). Caroline Pratt: Progressive Pedagogy In Statu Nascendi. Occasional Paper Series, 2014 (32). Retrieved from https://educate.bankstreet.edu/occasional-paper-series/vol2014/iss32/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Educate. It has been accepted for inclusion in Occasional Paper Series by an authorized editor of Educate. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Caroline Pratt: Progressive Pedagogy In Statu Nascendi By Jeroen Staring This article explores two themes in the life of Caroline Pratt, founder of the Play School, later the City and Country School. These themes, central to Harriet Cuffaro’s values as a teacher and scholar, are Pratt’s early progressive pedagogy, developed during experimental shopwork between 1901 and 1908; and her theories on play and toys, developed while observing children play with her Do-With Toys and Unit Blocks between 1908 and 1914. Focusing on her early and previously unexplored writings, this article illustrates how Caroline Pratt developed a coherent theory of innovative progressive pedagogy. Figure 1 (left). Original drawing of Do-With doll, by Caroline Pratt. Figure 2 (right): Two wooden, jointed Do-With dolls. (Photo: Jeroen Staring, 2011; Courtesy City and Country School, New York City) 46 | Occasional Paper Series 32 bankstreet.edu/ops Caroline Pratt’s Education In 1884, Caroline Louise Pratt, age 17, had her first teaching experience at the summer session of a school near her hometown, Fayetteville, New York. -

New England Preparatory School Athletic Council

NEW ENGLAND PREPARATORY SCHOOL ATHLETIC COUNCIL EXECUTIVE BOARD PRESIDENT JAMES MCNALLY, RIVERS SCHOOL FIRST VICE-PRESIDENT: MARK CONROY, WILLISTON NORTHAMPTON SCHOOL SECRETARY: DAVID GODIN, SUFFIELD ACADEMY TREASURER: BRADLEY R. SMITH, BRIDGTON ACADEMY TOURNAMENT ADVISOR: RICK FRANCIS, F. WILLISTON NORTHAMPTON SCHOOL VICE-PRESIDENT IN CHARGE OF PUBLICATION: KATE TURNER, BREWSTER ACADEMY PAST PRESIDENTS KATHY NOBLE, PROCTOR ACADEMY RICK DELPRETE, F. HOTCHKISS SCHOOL MIDDLE SCHOOL REPRESENTATIVE: MARK JACKSON, DEDHAM COUNTRY DAY SCHOOL DISTRICT REPRESENTATIVES DISTRICT I BRADLEY R. SMITH, BRIDGTON ACADEMY SUSAN GARDNER, GOULD ACADEMY DISTRICT II KEN HOLLINGSWORTH, TILTON SCHOOL DISTRICT III ALAN MCCOY, PINGREE SCHOOL DICK MUTHER, TABOR ACADEMY DISTRICT IV DAVE GODIN, SUFFIELD ACADEMY TIZ MULLIGAN, WESTOVER SCHOOL 1 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Souders Award Recipients ................................................................ 3 Distinguished Service Award Winners ............................................... 5 Past Presidents ................................................................................. 6 NEPSAC Constitution and By-Laws .................................................. 7 NEPSAC Code of Ethics and Conduct ..............................................11 NEPSAC Policies ..............................................................................14 Tournament Advisor and Directors ....................................................20 Pegging Dates ...................................................................................21 -

Massachusetts Grade 7 Immunization Survey Results 2013-2014

Massachusetts Grade 7 Immunization Survey Results 2013‐2014 The Massachusetts Department of Public Health Immunization Program is pleased to make available the 2013‐2014 Massachusetts grade 7 immunization survey results by school. Please be aware that the data are limited in a number of ways, including those listed below. Data release standards do not allow for data to be shared for schools with fewer than 30 reported students in grade 7. Schools that reported fewer than 30 students in grade 7 are indicated (†). Not all schools return their survey. Schools without data due to non‐response are indicated (*). Data were collected in the fall, but immunization data are often updated throughout the year and rates (during the same school year) may be higher than reported due to additional children receiving immunizations or bringing records to school. Also, the student body is dynamic and as students arrive and leave school, the immunization rates are impacted. Children are allowed a medical or religious exemption to one or more vaccines. Children without the required number of doses of vaccine do not necessarily have an exemption on file. Children without a record of vaccination, but with serologic proof of immunity to certain diseases (measles, mumps, rubella, hepatitis b and varicella), meet school entry requirements, but may not be counted as vaccinated. All data are self‐reported by the schools and discrepancies may exist. The Immunization Program continues to work with schools to resolve discrepancies and update immunization data, -

34829 PS Newsletter.Indd

The ® Scholarly News for Steppingstone Placement Schools The Steppingstone Academy NOVEMBER 2011 Placement Schools Steppingstone Gala Beaver Country Day School Steppingstone’s Pep Rally Gala surpassed all Belmont Day School Belmont Hill School expectations on Wednesday, November 2 at Boston College High School The Charles Hotel in Cambridge. This year’s Boston Latin Academy event celebrated all of the placement schools Boston Latin School that partner with Steppingstone to set more Boston Trinity Academy Scholars on the path to college success. Many Boston University Academy Brimmer and May School thanks to all Scholars, families, placement Buckingham Browne & Nichols School schools, and donors for making the Gala so Cambridge School of Weston memorable. Steppingstone raised more than Commonwealth School $725,000 with 400 guests and 18 heads of Concord Academy school in attendance. Dana Hall School Dedham Country Day School Mike Danziger, Founder, and Kelly Glew, President & COO, Deerfield academy with Scholars from eight Steppingstone placement schools. Derby Academy The Dexter School Scholars Tour Colleges Fay School This past summer marked Steppingstone’s The Fessenden School second annual Overnight College Tour. The Governor’s Academy Steppingstone Advisors spent four days with 32 Holderness School The Meadowbrook School of Weston Scholars from August 23-26 visiting the Milton Academy following colleges: Amherst, UMass Amherst, Newton Country Day School Union, Skidmore, Mt. Holyoke, Rensselaer Noble and Greenough School Polytechnic Institute, Colgate University, and John d. O’Bryant School Syracuse University. The Park School Phillips Academy Steppingstone staff took more than 50 Phillips Exeter Academy Scholars this fall on college tours, including The Rivers School visits to Babson College and Boston College, and The Roxbury Latin School on tours sponsored by Steppingstone’s National Shady Hill School Partnership for Educational Access (NPEA) to St. -

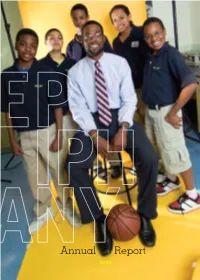

Annual Report 2009 EPIPHANY SERVES 86 STUDENTS in GRADES 5-8, ALL from ECONOMICALLY DISADVANTAGED BACKGROUNDS

Annual Report 2009 EPIPHANY SERVES 86 STUDENTS IN GRADES 5-8, ALL FROM ECONOMICALLY DISADVANTAGED BACKGROUNDS. MOST ARE ADMITTED BY LOTTERY, BUT WE RESERVE 20% OF OUR SPOTS FOR CHILDREN INVOLVED WITH THE MASSACHUSETTS DEPARTMENT OF CHILDREN & FAMILIES. BECAUSE OF OUR CLOSE PARTNERSHIP WITH FAMILIES, SIBLINGS ARE AUTOMATICALLY ADMITTED. WE CONTINUE TO SERVE OUR MORE THAN 150 GRADUATES THROUGH OUR GROUND-BREAKING GRADUATE SUPPORT PROGRAM. AN EPIPHANY EDUCATION IS BASED ON INDIVIDUALIZED ATTENTION AND ESSENTIAL SKILL-BUILDING, AND WE PROVIDE STUDENTS WITH FAR-REACHING WEBS OF SUPPORT. WE REQUIRE TWELVE HOUR SCHOOL DAYS, SMALL CLASSES, AND TUTORING. WE SERVE THREE MEALS DAILY, OFFER INTERSCHOLASTIC SPORTS AND FITNESS PROGRAMS, AND ENSURE STUDENTS RECEIVE IMPORTANT MEDICAL CARE. WE PROVIDE ALL GRADE LEVELS WITH HIGH- QUALITY PROGRAMMING ELEVEN MONTHS A YEAR, KEEPING STUDENTS LEARNING, ENGAGED, AND SAFE. MANY OF OUR GRADUATES REMAIN ACTIVE MEMBERS OF OUR COMMUNITY. WE DO EVERYTHING IN OUR POWER TO ENSURE THAT EACH CHILD WE SERVE SUCCEEDS IN SCHOOL AND LIFE. NEVER GIVE UP ON A CHILD. Dear Friends, 1 9 0 Every day at Epiphany offers its share of inspiration. : R A Students develop confidence and unlock their talents. In what feels like a moment, they emerge from childhood more mature and accomplished, ready for the challenges of high school. This year’s Y N graduating class had many students who arrived at Epiphany with their share of struggles. Four years A later, however, as a result of their hard work and the support and education Epiphany provides, each H P has achieved an extraordinary amount. Collectively, they have grown into exceptional students and I P young people. -

Progressive Education

PROGRESSIVE EDUCATION Lessons fronn the Past and Present Susan F. Semel, Alan R. Sadovnik, and Ryan W. Coughlan Progressive education is one of the most enduring educational reform move ments in this country, with a lifespan of over one hundred years. Although as noted earlier, it waxes and wanes in popularity, many of its practices now appear so regularly in both private and public schools as to have become almost mainstream. But from the schools that were the pioneers, what useful ■ lessons can we learn? The histories of the early progressive schools profiled in ■part 1 illustrate what happened to some of the progressive schools founded in I jhe first part of the twentieth century. But even now, they serve as important reminders for educators concerned with the competing issues of stability and change in schools with particular progressive philosophies—reminders, spe cifically, of the complex nature of school reform.' As we have seen in these histories, balancing the original intentions of progressive founders with the known demands upon practitioners has been the challenge some of the schools have met successfully and others have not. As contemporary American educators consider the school choice movement, the burgeoning expansion of charter schools, and the growing focus on stan- dards-based testing and accountability measures, they would do well to look back for guidance at some of the original schools representative of the “new education.” Particularly instructive. The Dalton School and The City and 374 SUSAN F. SEMEL ET AL. Country School are both urban independent schools that have enjoyed strong and enduring leaders, well-articulated philosophies and accompanying ped agogic practice, and a neighborhood to supply its clientele. -

Early Steps Celebration 30Th Anniversary Thursday, May 18, 2017 the University Club New York, NY

Benefit Early Steps Celebration 30th Anniversary Thursday, May 18, 2017 The University Club New York, NY Early Steps 540 East 76th Street • New York, NY 10021 www.earlysteps.org • 212.288.9684 Horace Mann School and all of our Early Steps students and families, past and present, join in celebrating Early Steps’ 30 Years as A Voice for Diversity in NYC Independent Schools Letter from our Director Dear Friends, For nearly three decades, it has been my joy and re- sponsibility to guide the parents of children of color through the process of applying to New York City in- dependent schools for kindergarten and first grade, helping them to realize their hopes and dreams for their children. While over 3,500 students of color entered school with the guidance of Early Steps, it is humbling to know that the impact has been so much greater. We hear time and © 2012 Victoria Jackson Photography again how families, schools and lives have been trans- formed as a result of the doors of opportunity that were opened with the help of Early Steps. Doors where academic excellence is the norm and children learn and play with others whose life’s experiences are not the same as theirs, benefitting all children. We are proud of our 30-year partnership with now over 50 New York City independent schools who nurture, educate and challenge our children to be the best that they can be. They couldn’t be in better hands! Tonight we honor four Early Steps alumni. These accomplished young adults all benefited from the wisdom of their parents who knew the importance of providing their children with the best possible education beginning in Kindergarten. -

An Open Letter on Behalf of Independent Schools of New England

An Open Letter on Behalf of Independent Schools of New England, We, the heads of independent schools, comprising 176 schools in the New England region, stand in solidarity with our students and with the families of Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida. The heart of our nation has been broken yet again by another mass shooting at an American school. We offer our deepest condolences to the families and loved ones of those who died and are grieving for the loss of life that occurred. We join with our colleagues in public, private, charter, independent, and faith-based schools demanding meaningful action to keep our students safe from gun violence on campuses and beyond. Many of our students, graduates, and families have joined the effort to ensure that this issue stays at the forefront of the national dialogue. We are all inspired by the students who have raised their voices to demand change. As school leaders we give our voices to this call for action. We come together out of compassion, responsibility, and our commitment to educate our children free of fear and violence. As school leaders, we pledge to do all in our power to keep our students safe. We call upon all elected representatives - each member of Congress, the President, and all others in positions of power at the governmental and private-sector level – to take action in making schools less vulnerable to violence, including sensible regulation of fi rearms. We are adding our voices to this dialogue as a demonstration to our students of our own commitment to doing better, to making their world safer. -

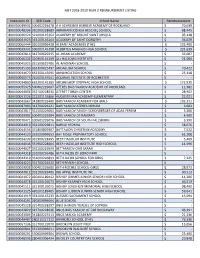

MST 2018-2019 Year 2 Reimbursement Listing

MST 2018-2019 YEAR 2 REIMBURSMENT LISTING Institution ID SED Code School Name Reimbursement 800000039032 500402226478 A H SCHREIBER HEBREW ACADEMY OF ROCKLAND $ 70,039 800000048206 310200228689 ABRAHAM JOSHUA HESCHEL SCHOOL $ 68,445 800000046124 321000145364 ACADEMY OF MOUNT SAINT URSULA $ 95,148 800000041923 353100145263 ACADEMY OF SAINT DOROTHY $ 36,029 800000060444 010100996428 ALBANY ACADEMIES (THE) $ 102,490 800000039341 500101145198 ALBERTUS MAGNUS HIGH SCHOOL $ 231,639 800000042814 342700629235 AL-IHSAN ACADEMY $ 33,087 800000046332 320900145199 ALL HALLOWS INSTITUTE $ 21,084 800000045025 331500629786 AL-MADINAH SCHOOL $ - 800000035193 662300625497 ANDALUSIA SCHOOL $ 70,422 800000034670 662300145095 ANNUNCIATION SCHOOL $ 25,148 800000050573 261600167041 AQUINAS INSTITUTE OF ROCHESTER $ - 800000034860 662200145185 ARCHBISHOP STEPINAC HIGH SCHOOL $ 172,930 800000055925 500402229697 ATERES BAIS YAAKOV ACADEMY OF ROCKLAND $ 12,382 800000044056 332100228530 ATERET TORAH CENTER $ 28,962 800000051126 222201155866 AUGUSTINIAN ACADEMY-ELEMENTARY $ 22,021 800000042667 342800226480 BAIS YAAKOV ACADEMY FOR GIRLS $ 103,321 800000087003 342700226221 BAIS YAAKOV ATERES MIRIAM $ 3,683 800000043817 331500229003 BAIS YAAKOV FAIGEH SCHONBERGER OF ADAS YEREIM $ 5,306 800000039002 500401229384 BAIS YAAKOV OF RAMAPO $ 4,980 800000070471 590501226076 BAIS YAAKOV OF SOUTH FALLSBURG $ 3,390 800000044016 332100229811 BARKAI YESHIVA $ 58,076 800000044556 331800809307 BATTALION CHRISTIAN ACADEMY $ 7,522 800000044120 332000999653 BAY RIDGE PREPARATORY SCHOOL -

Program Program at a Glance

2012 NAIS AnnuAl CoNference februAry 29 – mArCh 2 SeAttle Program Program at a Glance...............................................2 Speakers............................................................................4 Floor Plans......................................................................8 Conference Highlights.........................................10 The NAIS Annual Conference is the yearly gathering and Conference Planning Worksheet celebration for the independent and Workshop Tracks...........................................12 school community and is Detailed Program geared toward school leaders Wednesday...........................................................14 in the broadest sense. Heads, administrators, teachers, and Thursday............................................................. 20 trustees are welcome participants Friday......................................................................36 in the exhibit hall, general Exhibit Hall and Member sessions, and workshops focused Resource Center...................................................... 50 on important topics of today. Teacher and Administrative Placement Firms.......................................................71 Acknowledgments..................................................74 New to the CoNference? Is this your first time attending the NAIS Annual Conference? Welcome! Please stop by the NAIS Member Resource Center in the exhibit hall to learn more about NAIS or contact us at [email protected]. WWelcome!Welcome!elcome! dear colleagUeS: Welcome -

Access, Equity and Activism: TEACHING the POSSIBLE! Progressivenational Education Conference Network New York City October 8-10, 2015

1 Access, Equity and Activism: TEACHING THE POSSIBLE! Progressive Education Network National Conference New York City PEN_Conference_2015.indd 1 October 8-10, 2015 9/29/15 2:25 PM 2 Mission and History of the Progressive Education Network “The Progressive Education Network exists to herald and promote the vision of progressive education on a national basis, while providing opportunities for educators to connect, support, and learn from one another.” In 2004 and 2005, The School in Rose Valley, PA, celebrated its seventy- fifth anniversary by hosting a two-part national conference, Progressive Education in the 21st Century. Near the end of the conference, a group of seven educators from public and private schools around the country rallied to a call-to-action to revive the Network of Progressive Educators, which had been inactive since the early 1990s. Inspired by the progressive tenets of the conference, the group shared a grand collective mission: to establish a national group to rise up, protect, clarify, and celebrate the principles of progressive education and to fashion a revitalized national educational vision. This group, “The PEN Seven” (Maureen Cheever, Katy Dalgleish, Tom Little, Kate (McLellan) Blaker, John Pecore, Lisa Shapiro, and Terry Strand) hosted the organization’s first national conference in San Francisco in 2007. As a result of the committee’s efforts, the Progressive Education Network (PEN) was formed and in 2009 was incorporated as a 501 (c) 3 charitable, non-profit organization. Biannual conferences, supported by PEN and produced by various committees, followed in DC, Chicago, and LA, with attendance growing from 250 to 950. -

2007 Boston, Ma

REshAPING TRADITIONS NOv 29 – DEC 1, 2007 BOSTON, MA PEOPLE OF COLOR CONFERENCE CONFERENCE STUDENT DIVERSITY LEADERshIP CONFERENCE PROGRAM www.nais.org/go/pocc WELCOME NAIS WELCOME The National Association of Independent Schools (NAIS) is honored to host the 0th People of Color Conference (PoCC) and the 14th Student Diversity Leadership Conference (SDLC) in Boston, Massachusetts. Coming to Boston for PoCC/SDLC is historically significant as NAIS originated at offices near Faneuil Hall on Tremont Street. The rich density of inde- pendent schools in and around Boston, many with historic commitments to and success in building and sustaining inclu- sive school communities, makes bringing the conferences to South Boston ideal, particularly as this part of the city under- goes revitalization while PoCC has undergone a redesign. The new approach to PoCC is actually a return to its original purpose, providing people of color in our schools a sanctuary and a “voice,” a means for support and networking, and a chance to celebrate their roles in independent schools. What does this re-direction mean and how will the program itself change? The differences in programming can be All PoCC functions will be held at the Boston Convention and Exhibition Center (BCEC) 415 SUMMER STREET, BOSTON, MA 02210 summarized in the following ways: All SDLC functions will be held at the Boston Convention and PoCC workshop themes will be more focused on providing Exhibition Center (BCEC) and the Westin Boston Waterfront. leadership and professional and personal development for people of color. contributions and work of independent school adults and students of color — are welcome and encouraged to attend.