Lesotho 2015 Human Rights Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Press Statement by the Family of Lt General Maaparankoe Mahao on Sadc Report: 16 February 2016, Maseru, Lesotho

PRESS STATEMENT BY THE FAMILY OF LT GENERAL MAAPARANKOE MAHAO ON SADC REPORT: 16 FEBRUARY 2016, MASERU, LESOTHO Lt General Maaparankoe Mahao’s family has had the opportunity to study Justice Mphaphi Phumaphi Commission of Inquiry Report. As all of us will remember, the Commission was established by SADC to investigate the circumstances surrounding the death of General Mahao and the alleged mutiny against the current leadership of the Lesotho Defence Force (LDF). The Report was endorsed by the SADC Double Troika at its Summit held in Gaborone, Botswana on 18th January, 2016 with an injunction on the Lesotho Government to publish it and implement it. Lt General Mahao’s family once again wishes to express its gratitude to SADC for its efforts in the search for lasting peace and stability in the Kingdom of Lesotho and, in particular, to SADC’s unwavering commitment to get to the bottom of how and why Lt General Mahao was killed on 25th June, 2015. We further express our sincere appreciation of the thorough and professional work carried out by Justice Phumaphi’s Commission of Inquiry in the discharge of its mandate. We are fully aware of the very difficult conditions under which the Commission operated; especially the obstructions it encountered from some with vested interest to have the truth forever buried. Two principal objectives were at the heart of SADC’s decision to establish the Commission of Inquiry. These were the death of Lt General Mahao and the alleged mutiny within the ranks of the LDF. Around the death of Lt General Mahao, some significant progress was made in so far as the Commission ascertained certain facts which dispel and lay to rest the false claims made by the LDF with regards to why he was killed. -

The Impact of Political Parties and Party Politics On

EXPLORING THE ROLE OF POLITICAL PARTIES AND PARTY SYSTEMS ON DEMOCRACY IN LESOTHO by MPHO RAKHARE Student number: 2009083300 Submitted in the fulfilment of the requirements for the Magister Degree in Governance and Political Transformation in the Programme of Governance and Political Transformation at the University of Free State Bloemfontein February 2019 Supervisor: Dr Tania Coetzee TABLE OF CONTENTS Pages DECLARATION .................................................................................................................................... 4 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ...................................................................................................................... 5 List of abbreviations and acronyms ................................................................................................... 6 LIST OF TABLES ................................................................................................................................. 8 Chapter 1 ............................................................................................................................................... 9 Introduction to research ....................................................................................................................... 9 1.1 Motivation ........................................................................................................................................ 9 1.2 Problem statement ..................................................................................................................... -

FOL Newsletter 3QTR

Metsoalle ea Lesotho Friends of Lesotho Third Quarter 2014 Newsletter Newsletter Features Clickable Links!! Download the newsletter from the FOL FOL President Appointed website www.friendsoflesotho.org and you will be able to click on all the Honorary Consul website addresses. Friends of Lesotho President Scott Rosenberg was appointed Honorary Consul by the Lesotho Embassy in Washington, DC. He will represent Lesotho in Ohio and the Midwest and help facilitate greater cooperation between the two countries to promote Lesotho’s trade, tourism, investment, and cultural activities to Ameri- cans, and he will also assume protocol responsibilities for visiting Basotho dignitaries. The current Ambassador to the US, serving in the Washington DC consulate, is Ambassador Molapi Sepetane. Scott Rosenberg (R) with Lesotho Minister of Protocol Moshuli Leteka, Summer 2014, Maseru. Photo Credit: Thabo Moseunyane Was There a Coup or Not? By Ella Kwisnek, RPCV 92-94, Lesotho Agricultural College, [email protected] A quarterly newsletter is not an ideal place for fast-breaking news, so thanks to RPCV Ella Kwis- nek for compiling this log of events that made front pages on world newspapers during August and Sept 2014. ~ Ed. What happened? On Saturday, August 30, 2014, there was a reported “coup d'état attempt by the military” in Lesotho. Soldiers reportedly disarmed police and one police officer was killed as the result of an ex- change of gunfire between soldiers and police. Prime Minister Motsoahae Thomas Thabane fled to South Africa and accused his deputy Mothetjoa Metsing Photo Credit: Linda Henry, RPCV of being behind the army's actions. Foreign Ministers of the Southern African Development Community (SADC) States met with the leaders of the three political parties that made up Lesotho’s Coalition govern- ment in an attempt to resolve the conflict. -

Doctoral Dissertation

Doctoral Dissertation A Critical Assessment of Conflict Transformation Capacity in the Southern African Development Community (SADC): Deepening the Search for a Self-Sustainable and Effective Regional Infrastructure for Peace (RI4P) MALEBANG GABRIEL GOSIAME G. Graduate School for International Development and Cooperation Hiroshima University September 2014 A Critical Assessment of Conflict Transformation Capacity in the Southern African Development Community (SADC): Deepening the Search for a Self-Sustainable and Effective Regional Infrastructure for Peace (RI4P) D115734 MALEBANG GABRIEL GOSIAME G. A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School for International Development and Cooperation of Hiroshima University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2014 DECLARATION I hereby declare that this doctoral thesis is in its original form. The ideas expressed and the research findings recorded in this doctoral thesis are my own unaided work written by me MALEBANG GABRIEL GOSIAME G. The information contained herein is adequately referenced. It was gathered from primary and secondary sources which include elite interviews, personal interviews, archival and scholarly materials, technical reports by both local and international agencies and governments. The research was conducted in compliance with the ethical standards and guidelines of the Graduate School for International Development and Cooperation (IDEC) of Hiroshima University, Japan. The consent of all respondents was obtained using the consent form as shown in Appendix 3 for the field research component of the study and for use of the respondent’s direct words as quoted therein. iii DEDICATIONS This dissertation is dedicated to the loving memory of my mother Roseline Keitumetse Malebang (1948 – 1999) and to all the people of Southern Africa. -

Lesotho Country Report BTI 2018

BTI 2018 Country Report Lesotho This report is part of the Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Transformation Index (BTI) 2018. It covers the period from February 1, 2015 to January 31, 2017. The BTI assesses the transformation toward democracy and a market economy as well as the quality of political management in 129 countries. More on the BTI at http://www.bti-project.org. Please cite as follows: Bertelsmann Stiftung, BTI 2018 Country Report — Lesotho. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2018. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Contact Bertelsmann Stiftung Carl-Bertelsmann-Strasse 256 33111 Gütersloh Germany Sabine Donner Phone +49 5241 81 81501 [email protected] Hauke Hartmann Phone +49 5241 81 81389 [email protected] Robert Schwarz Phone +49 5241 81 81402 [email protected] Sabine Steinkamp Phone +49 5241 81 81507 [email protected] BTI 2018 | Lesotho 3 Key Indicators Population M 2.2 HDI 0.497 GDP p.c., PPP $ 3029 Pop. growth1 % p.a. 1.3 HDI rank of 188 160 Gini Index 54.2 Life expectancy years 53.6 UN Education Index 0.528 Poverty3 % 78.0 Urban population % 27.8 Gender inequality2 0.549 Aid per capita $ 38.2 Sources (as of October 2017): The World Bank, World Development Indicators 2017 | UNDP, Human Development Report 2016. Footnotes: (1) Average annual growth rate. (2) Gender Inequality Index (GII). (3) Percentage of population living on less than $3.20 a day at 2011 international prices. Executive Summary Lesotho has been shaken by a series of destabilizing events during the period under review (2015- 2017). -

Elections in a Time of Instability Challenges for Lesotho Beyond the 2015 Poll Dimpho Motsamai

ISSUE 3 | APRIL 2015 Southern Africa Report Elections in a time of instability Challenges for Lesotho beyond the 2015 poll Dimpho Motsamai Summary The Kingdom of Lesotho stands at a crossroads. After an attempted coup in August 2014, Parliament was prorogued and elections were brought forward by two years. Lesotho citizens went to the polls on 28 February, but it is unlikely that the outcome of the election – a coalition led by the Democratic Congress – will solve the cyclical and structural shortcomings of the country’s politics. Parties split and splinter; violence breaks out both before and after polls; consensus is non-existent, even among coalition partners, and manoeuvring for position trumps governing for the good of the country. SADC’s ‘Track One’ mediation has had some success but it will take political commitment, currently lacking, to set Lesotho on a sustainable political and developmental path. LESOTHO HELD SNAP ELECTIONS in February 2015 two years ahead of schedule, to resolve a political and constitutional deadlock amid an uncertain security situation. The election was to install a new five-year government after months of government paralysis following the acrimonious collapse of its governing coalition in June last year. Then-prime minister Thomas Thabane suspended Parliament to avoid a vote of no confidence pushed by the opposition and supported by his coalition partner, then-deputy prime minister Mothejoa Metsing.1 What followed was an attempted coup d’état, staged in August by a dismissed commander of the Lesotho Defence Force (LDF) and leading to disruptions in the country’s civil-military equilibrium.2 The underlying and even defining dimension of these developments is reflected in Lesotho’s relatively short democratic history, typified by the entrenched politicisation of state and security administration, fractious politics and violent patterns of contestation over state power. -

Urgent Action

1st update on UA: 263/15 Index: AFR 33/4411/2016 Lesotho Date: 8 July 2016 URGENT ACTION CONTINUED ILL-TREATMENT OF DETAINED SOLDIERS The court martial of 23 members of the Lesotho Defence Force (LDF) for mutiny charges has been postponed to 6 September. Sixteen of the accused remain in custody. The authorities continue to subject the detainees to ill-treatment. On 29 April the Lesotho Appeal Court ruled that the court martial should proceed, and overturned previous High Court orders that the remaining detainees be released on bail. As the Lesotho Defence Force (LDF) had not complied with previous High Court rulings, the defence team approached the Appeal Court in an attempt to compel the LDF to uphold these orders. As such, 16 of the 23 accused soldiers remain in Maseru Maximum Security Prison, whilst the seven men on bail are required to report to barracks three times a day. This is despite the fact that a Southern African Development Community (SADC) Commission of Inquiry report found that there were anomalies relating to the charges of mutiny and recommended that the 23 soldiers facing mutiny charges be granted amnesty from criminal prosecution. Prison authorities subjected the detained soldiers to further ill-treatment as a result of a march organized by the detainees’ children on 16 June, Father’s Day. When the march was announced, five of the detained soldiers were placed in solitary confinement and denied food for a day. The wives of the detainees have also reported being stripped searched when visiting their husbands in prison. Opposition members of Parliament tried to visit the detainees after they were placed in solitary confinement but senior LDF officers refused their access and threatened them, saying that they would be shot if they did not leave the prison. -

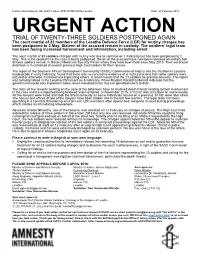

Urgent Action

Further information on UA: 263/15 Index: AFR 33/3481/2016 Lesotho Date: 23 February 2016 URGENT ACTION TRIAL OF TWENTY-THREE SOLDIERS POSTPONED AGAIN The court martial of 23 members of the Lesotho Defence Force (LDF) for mutiny charges has been postponed to 2 May. Sixteen of the accused remain in custody. The soldiers’ legal team has been facing increased harassment and intimidation, including arrest. The court martial of 23 soldiers charged with mutiny was due to continue on 1 February but has been postponed to 2 May. This is the second time the case is being postponed. Seven of the accused have now been released on military bail. Sixteen soldiers remain in Maseru Maximum Security Prison where they have been held since May 2015. Their continued detention is in contempt of several previous High Court orders for their release. The report of the Southern African Development Community (SADC) Commission of Inquiry into the situation in Lesotho made public in early February, found that there was no conclusive evidence of a mutiny plot and that some soldiers were tortured or otherwise ill-treated into implicating others. It recommends that the 23 soldiers be granted amnesty. The report was formally tabled in the Lesotho Parliament on 8 February. Prime Minister Pakalitha Mosisili indicated that the government would only implement some recommendations but has not specified which to date. The team of five lawyers working on the case of the detainees have all received death threats relating to their involvement in the case and have reported being followed and monitored. In November 2015, a ‘hit list’ was circulated on social media. -

The Assassination of Military Commanders In

117 Mokete Pherudi THE ASSASSINATION OF MILITARY Head of the Early Warning Unit at CISSA, Addis COMMANDERS IN LESOTHO: Ababa, Ethiopia. Email: TRIGGERS AND REACTIONS [email protected] Head, Regional Early Warning Centre, Directorate for DOI: https://dx.doi. Politics, Defence and Security Affairs, Southern African org/10.18820/24150509/ Development Community JCH43.v2.7 ISSN 0258-2422 (Print) ISSN 2415-0509 (Online) Abstract Journal for Contemporary This article investigates civil-military relations (CMR) in History Lesotho and its impact on political and security stability. 2018 43(2):117-133 The nature of CMR is unmasked by tracing the evolution of the Lesotho Defence Force (LDF) and the history of its © Creative Commons With politicisation. The assassinations of LDF commanders, Attribution (CC-BY) Lt-Gen Maaparankoe Mahao in 2015 and Lt-Gen Khoantle Motšomotšo in 2017, respectively, by members from within their ranks, are explored to illustrate how the undue involvement of the military in politics has contributed to instability in Lesotho. Other triggers contributing to the unstable situation are highlighted. The enquiry of this article is not only about the nature of CMR but how the regional body, the Southern African Development Community (SADC) has sought to intervene in Lesotho with the aim of firstly stabilising the politics and security of the country. SADC’s other aim has been the facilitating of security sector reforms that will, amongst other things, configure CMR such that the armed forces are accountable to civilian authority and they do not meddle in political contest. Keywords: Civil-military relations (CMR), Security Sector Reform (SSR), Lesotho Defence Force (LDF), Southern African Development Community (SADC). -

Towards an Explanation of the Recurrence of Military Coups in Lesotho

ASPJ Africa & Francophonie - 3rd Quarter 2017 Towards an Explanation of the Recurrence of Military Coups in Lesotho EVERISTO BENYERA, PHD* esotho’s history is littered with military coups, with the latest one—with questionable authenticity—complicating the already complicated role of the military in the South African country’s politics. This article un- packs what it terms a dangerous mix in Lesotho’s politics which pits the military against the monarch.1 This will be achieved by first exploring the history of monarch–military relations using the coloniality of power as the theoretical L 2 framework. This relationship is here cast as one of legitimisation, delegitimisa- tion, and relegitimisation.3 Some authors characterise the relationship as perpetu- ally antagonistic and maintain that it was never meant to work.4 Accordingly, the two institutions tend to have a love–hate relationship, at times opposing each other while also reinforcing one another on another level. In this relationship, tensions occur when the military delegitimises the monarch and the state, leading in turn to the monarchy seeking to relegitimise itself. The extent of these tensions is expressed—among other things—through the various military coup d’états that have rocked the kingdom in the clouds for decades. In Lesotho, the latest version of military coups occurred on 1 September 2014 and was the sixth successful coup in the country since 1970. Unlike other coups before it, this one was very different because it was disputed by many, in- cluding Lesotho’s powerful and influential only neighbour, South Africa, and the *Dr Everisto Benyera is a senior lecturer in the Department of Political Sciences at the University of South Africa in Pretoria, South Africa. -

Amnesty International Report 2016/17 Amnesty International

AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL REPORT 2016/17 AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. First published in 2017 by Except where otherwise noted, This report documents Amnesty Amnesty International Ltd content in this document is International’s work and Peter Benenson House, licensed under a Creative concerns through 2016. 1, Easton Street, Commons (attribution, non- The absence of an entry in this London WC1X 0DW commercial, no derivatives, report on a particular country or United Kingdom international 4.0) licence. territory does not imply that no https://creativecommons.org/ © Amnesty International 2017 human rights violations of licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode concern to Amnesty International Index: POL 10/4800/2017 For more information please visit have taken place there during ISBN: 978-0-86210-496-2 the permissions page on our the year. Nor is the length of a website: www.amnesty.org country entry any basis for a A catalogue record for this book comparison of the extent and is available from the British amnesty.org depth of Amnesty International’s Library. concerns in a country. Original language: English ii Amnesty International -

Amnesty International Report 2017/18

AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. First published in 2018 by Except where otherwise noted, This report documents Amnesty Amnesty International Ltd content in this document is International’s work and concerns Peter Benenson House, licensed under a through 2017. 1, Easton Street, CreativeCommons (attribution, The absence of an entry in this London WC1X 0DW non-commercial, no derivatives, report on a particular country or United Kingdom international 4.0) licence. territory does not imply that no https://creativecommons.org/ © Amnesty International 2018 human rights violations of licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode concern to Amnesty International Index: POL 10/6700/2018 For more information please visit have taken place there during the ISBN: 978-0-86210-499-3 the permissions page on our year. Nor is the length of a website: www.amnesty.org country entry any basis for a A catalogue record for this book comparison of the extent and is available from the British amnesty.org depth of Amnesty International’s Library. concerns in a country. Original language: English ii Amnesty International Report 2017/18 AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL