A Case Study of Celebrity Chef Gennaro ‘Gino’ D’Acampo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NOMINATIONS with WINNERS *HIGHLIGHTED 10 May 2015 FELLOWSHIP JON SNOW

NOMINATIONS WITH WINNERS *HIGHLIGHTED 10 May 2015 FELLOWSHIP JON SNOW SPECIAL AWARD JEFF POPE LEADING ACTOR BENEDICT CUMBERBATCH Sherlock – BBC One TOBY JONES Marvellous – BBC Two JAMES NESBITT The Missing – BBC One *JASON WATKINS The Lost Honour of Christopher Jefferies - ITV LEADING ACTRESS *GEORGINA CAMPBELL Murdered by My Boyfriend – BBC Three KEELEY HAWES Line of Duty – BBC Two SARAH LANCASHIRE Happy Valley – BBC One SHERIDAN SMITH Cilla - ITV SUPPORTING ACTOR ADEEL AKHTAR Utopia – Channel 4 JAMES NORTON Happy Valley – BBC One *STEPHEN REA The Honourable Woman – BBC Two KEN STOTT The Missing – BBC One SUPPORTING ACTRESS *GEMMA JONES Marvellous – BBC Two VICKY MCCLURE Line of Duty – BBC Two AMANDA REDMAN Tommy Cooper: Not like That, Like This - ITV CHARLOTTE SPENCER Glue – E4 ENTERTAINMENT PERFORMANCE *ANT AND DEC Ant and Dec’s Saturday Night Takeaway – ITV LEIGH FRANCIS Celebrity Juice – ITV2 GRAHAM NORTON The Graham Norton Show – BBC One CLAUDIA WINKLEMAN Strictly Come Dancing – BBC One FEMALE PERFORMANCE IN A COMEDY PROGRAMME OLIVIA COLMAN Rev. – BBC Two TAMSIN GREIG Episodes – BBC Two *JESSICA HYNES W1A – BBC Two CATHERINE TATE Catherine Tate’s Nan – BBC One MALE PERFORMANCE IN A COMEDY PROGRAMME *MATT BERRY Toast of London – Channel 4 HUGH BONNEVILLE W1A – BBC Two TOM HOLLANDER Rev. – BBC Two BRENDAN O’CARROLL Mrs Brown’s Boys – Christmas Special – BBC One SINGLE DRAMA A POET IN NEW YORK Aisling Walsh, Ruth Caleb, Andrew Davies, Griff Rhys Jones - Modern Television/BBC Two COMMON Jimmy McGovern, David Blair, Colin McKeown, Donna -

Celebrity Chefs As Brand and Their Cookbooks As Marketing

Celebrity Chefs as brand and their cookbooks as marketing communications This paper discusses how consumers understand and interpret celebrity chefs as brands and utilise the cookbooks as marketing communications of the benefits and values of the brand. It explores the literature around the concept of celebrity, identifying it as something which is consciously created with commercial intent to such an extent that to suggest celebrities become brands is not hyperbole (Turner, 2004). It discusses the celebrity chef: how they are created and their identity as marketing objects (Byrne et al, 2003). It discusses common constructions of the meaning of cookbooks as historical and cultural artefacts and as merchandise sold on the strength of their associated celebrity’s brand values (Brownlee & Hewer, 2007). The paper then discusses its findings against two research objectives: first to explore the meaning of celebrity chefs for consumers and second to suggest a mechanism of how this meaning is created. Using narrative analysis of qualitative interviews this paper suggests, that consumers understand and consume the celebrity chef brand in a more active and engaged way than traditional consumer goods brands can achieve. It also suggests, as a development from tradition views of cookbooks, that those written by the celebrity chef brands are acting as marketing communications for their brand values. Defining Celebrity Celebrity is much written about by social theorists (Marshall, 1997; Monaco, 1978) and as such there are many taxonomies of celebrity which Turner (2004) and discusses at some length in his work Most interesting for this work is the concept of the Star (Monaco, 1978), fame is achieved when their public persona eclipses their professional profile in the ways of Elizabeth Hurley or Paris Hilton. -

Media Nations 2019

Media nations: UK 2019 Published 7 August 2019 Overview This is Ofcom’s second annual Media Nations report. It reviews key trends in the television and online video sectors as well as the radio and other audio sectors. Accompanying this narrative report is an interactive report which includes an extensive range of data. There are also separate reports for Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales. The Media Nations report is a reference publication for industry, policy makers, academics and consumers. This year’s publication is particularly important as it provides evidence to inform discussions around the future of public service broadcasting, supporting the nationwide forum which Ofcom launched in July 2019: Small Screen: Big Debate. We publish this report to support our regulatory goal to research markets and to remain at the forefront of technological understanding. It addresses the requirement to undertake and make public our consumer research (as set out in Sections 14 and 15 of the Communications Act 2003). It also meets the requirements on Ofcom under Section 358 of the Communications Act 2003 to publish an annual factual and statistical report on the TV and radio sector. This year we have structured the findings into four chapters. • The total video chapter looks at trends across all types of video including traditional broadcast TV, video-on-demand services and online video. • In the second chapter, we take a deeper look at public service broadcasting and some wider aspects of broadcast TV. • The third chapter is about online video. This is where we examine in greater depth subscription video on demand and YouTube. -

Download This Document

Lane, S. and Fisher, S. (2015) 'The influence of celebrity chefs on a student population’, British Food Journal, 117 (2), pp. 614-628. Official URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-09-2013-0253 ResearchSPAce http://researchspace.bathspa.ac.uk/ This pre-published version is made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the reference above. Your access and use of this document is based on your acceptance of the ResearchSPAce Metadata and Data Policies, as well as applicable law:- https://researchspace.bathspa.ac.uk/policies.html Unless you accept the terms of these Policies in full, you do not have permission to download this document. This cover sheet may not be removed from the document. Please scroll down to view the document. The Influence of Celebrity Chefs on a Student Population 1. Introduction Celebrity is much written about by social theorists (McNamara, 2009; Ferri, 2010; Lawler, 2010) and as such there are many taxonomies of celebrity, which Turner (2010) discusses at length. The concept that celebrity is a ‘cultural formation that has a social function’ (Turner, 2010:11), and the contemporary significance of celebrity itself remains a key topic for debate (Couldry and Markham, 2007). Celebrities are considered as role models for millions of people, especially younger citizens (Couldry and Markham, 2007), who are the focus of this study. Pringle (2004:3) suggests that ‘celebrity sells’, and outlines the extent to which society becomes influenced by these figures due to their prevalence in everyday life. Becoming well-known public figures, where they have adversaries as well as fans (Henderson, 2011) celebrities have attracted significant literature, which is split on their benefit and detriment to society (Couldry and Markham, 2007). -

Special Issue

ISSUE 750 / 19 OCTOBER 2017 15 TOP 5 MUST-READ ARTICLES record of the week } Post Malone scored Leave A Light On Billboard Hot 100 No. 1 with “sneaky” Tom Walker YouTube scheme. Relentless Records (Fader) out now Tom Walker is enjoying a meteoric rise. His new single Leave } Spotify moves A Light On, released last Friday, is a brilliant emotional piano to formalise pitch led song which builds to a crescendo of skittering drums and process for slots in pitched-up synths. Co-written and produced by Steve Mac 1 as part of the Brit List. Streaming support is big too, with top CONTENTS its Browse section. (Ed Sheeran, Clean Bandit, P!nk, Rita Ora, Liam Payne), we placement on Spotify, Apple and others helping to generate (MusicAlly) love the deliberate sense of space and depth within the mix over 50 million plays across his repertoire so far. Active on which allows Tom’s powerful vocals to resonate with strength. the road, he is currently supporting The Script in the US and P2 Editorial: Paul Scaife, } Universal Music Support for the Glasgow-born, Manchester-raised singer has will embark on an eight date UK headline tour next month RotD at 15 years announces been building all year with TV performances at Glastonbury including a London show at The Garage on 29 November P8 Special feature: ‘accelerator Treehouse on BBC2 and on the Today Show in the US. before hotfooting across Europe with Hurts. With the quality Happy Birthday engagement network’. Recent press includes Sunday Times Culture “Breaking Act”, of this single, Tom’s on the edge of the big time and we’re Record of the Day! (PRNewswire) The Sun (Bizarre), Pigeons & Planes, Clash, Shortlist and certain to see him in the mix for Brits Critics’ Choice for 2018. -

NIGELLA LAWSON in CONVERSATION with ANNABEL CRABB Concert Hall, Sydney Opera House, Wednesday 20 January 2016

MEDIA RELEASE Friday 20 November 2015 GP tickets on sale Friday 27 November SYDNEY OPERA HOUSE PRESENTS NIGELLA LAWSON IN CONVERSATION WITH ANNABEL CRABB Concert Hall, Sydney Opera House, Wednesday 20 January 2016 The woman who put the pleasure back into food, Nigella Lawson, will bring her trademark wit and warmth to the Sydney Opera House this summer in the latest in a series of sold-out appearances by contemporary culinary stars, including Yotam Ottolenghi, Alice Waters and Jamie Oliver. Lawson will take to the Concert Hall stage on 20 January, 2016 for an evening of conversation with the woman who puts the politics into food, the host of the ABC’s Kitchen Cabinet Annabel Crabb. Lawson’s Sydney Opera House appearance coincides with the launch of her first book in three years, Simply Nigella, which – as its title suggests – encapsulates Lawson’s joyfully relaxed and uncomplicated approach to food. Her debut cookbook, How to Eat: The Pleasures and Principles of Good Food, and television show Nigella Bites made Lawson a household name. She has since become a prominent figure on the Food Network, Foxtel and Channel 10. Lawson was named Author of the Year by the British Book Awards for How to Be a Domestic Goddess: Baking and the Art of Comfort Cooking – hailed as the book that launched a thousand cupcakes – and was voted Best Food Personality in a readers’ vote at the Observer Food Monthly Awards in 2014. Ann Mossop, Head of Talks and Ideas at the Sydney Opera House, says “Nigella Lawson has charmed us all with her approach to food and cooking, and we cannot wait to welcome her to the Concert Hall stage with Ideas at the House favourite, Annabel Crabb. -

Danielle Lloyd Forced to Defend 'Intense' Cosmetic Treatment | Daily Mail Online

Danielle Lloyd forced to defend 'intense' cosmetic treatment | Daily Mail Online Cookie Policy Feedback Like 3.9M Follow DailyMail Thursday, May 5th 2016 10AM 14°C 1PM 17°C 5-Day Forecast Home News U.S. Sport TV&Showbiz Australia Femail Health Science Money Video Travel Fashion Finder Latest Headlines TV&Showbiz U.S. Showbiz Headlines Arts Pictures Showbiz Boards Login 'It's not actually lipo': Danielle Lloyd forced Site Web to defend 'intense' cosmetic treatment after Like Follow Daily Mail Celeb @DailyMailCeleb bragging about getting her body summer- Follow ready Daily Mail Celeb By BECKY FREETH FOR MAILONLINE +1 Daily Mail Celeb PUBLISHED: 16:41, 20 January 2015 | UPDATED: 18:12, 20 January 2015 34 89 DON'T MISS shares View comments 'Ahh to be a Size 6 again': Gogglebox star Danielle Lloyd's Instagram followers voiced their concern on Tuesday, when the slender starlet posted Scarlett Moffatt shares a picture of her receiving what she said was intense 'lipo treatment'. a throwback of 'a very skinny minnie me' after Users who thought she was having the cosmetic procedure 'liposuction' - which removes body fat - vowing to overhaul her were quickly corrected by the glamour model in her defence. lifestyle The 31-year-old, who claimed she was 'getting ready for summer' in the initial Instagram snap, insisted it was a skin-tightening procedure known as a 'radio frequency treatment'. Chrissy Teigen reveals her incredible Scroll down for video post-baby body as she cuddles little Luna in sweet photos shared by her mother Relishing motherhood -

A Study of Celebrity Cookbooks, Culinary Personas, and Inequality

G Models POETIC-1168; No. of Pages 22 Poetics xxx (2014) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Poetics journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/poetic Making change in the kitchen? A study of celebrity cookbooks, culinary personas, and inequality Jose´e Johnston *, Alexandra Rodney, Phillipa Chong University of Toronto, Department of Sociology, 725 Spadina Avenue, Toronto, Ontario M5S 2J4, Canada ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history: In this paper, we investigate how cultural ideals of race, class and Available online xxx gender are revealed and reproduced through celebrity chefs’ public identities. Celebrity-chef status appears attainable by diverse voices Keywords: including self-trained cooks like Rachael Ray, prisoner turned high- Food end-chef Jeff Henderson, and Nascar-fan Guy Fieri. This paper Persona investigates how food celebrities’ self-presentations – their culinary Cookbooks personas – relate to social hierarchies. Drawing from literature on Celebrity chefs the sociology of culture, personas, food, and gender, we carry out an Gender inductive qualitative analysis of celebrity chef cookbooks written Inequality by stars with a significant multi-media presence. We identify seven distinct culinary personas: homebody, home stylist, pin-up, chef- artisan, maverick, gastrosexual, and self-made man. We find that culinary personas are highly gendered, but also classed and racialized. Relating these findings to the broader culinary field, we suggest that celebrity chef personas may serve to naturalize status inequities, and our findings contribute to theories of cultural, culinary and gender stratification. This paper supports the use of ‘‘persona’’ as an analytical tool that can aid understanding of cultural inequalities, as well as the limited opportunities for new entrants to gain authority in their respective fields. -

British Street Food • Working for the Street Food Revolution 2 Selection of Coverage

2019 Review British Street Food • Working For The Street Food Revolution 2 Selection Of Coverage C4’s Sunday Brunch ITV News MediaMedia CoverageCoverage ReportReport 20192019 British Street Food • Working For The Street Food Revolution 3 About Us ■ Formed in 2009 ■ For young street food traders to showcase their talent ■ To make good food accessible to everyone ■ And to celebrate the grass roots street food movement British Street Food • Working For The Street Food Revolution 4 Founder – Richard Johnson ■ One of the 1,000 most influential people in London for four years running according to the Evening Standard ■ Award-winning food journalist and consultant ■ Writer / presenter of The Food Programme on BBC Radio 4 ■ Author of the best-selling book Street Food Revolution ■ Johnson has been the host of Full on Food for BBC2, Kill It, Cook It, Eat It for BBC3, as well as supertaster for ITV’s Taste The Nation and judge on Channel 4’s Iron Chef and Cookery School British Street Food • Working For The Street Food Revolution 5 About Us – Our Vision “ To share street food with the world. Michelin has just awarded its first stars to street food chefs. With the British Street Food Awards - and now the European Street Food Awards - we will find the Michelin stars of tomorrow.” British Street Food • Working For The Street Food Revolution 6 “ Traders compete in five regional heats, from May to August, with a big national final in September. 2019 attendance? Over 45,000 people.” British Street Food • Working For The Street Food Revolution 7 The Judges -

MUHAMMAD ALI Celebrating the Life of a Boxing Legend and Activist

DUVET DAYS: The top ten excuses for calling in sick in Britain Photo Credit: PA Images FOOD FOR THOUGHT All you need to know about staying healthy MUHAMMAD ALI Celebrating the life of a boxing legend and activist Vision StanmoreEdgware | Edition 3 | July 2016 ViSIOnStanmoreEdgware edition3 | to advertise call 01442 254894 V1 Buy - Rent - Sell - Let PARKERS For a FREE no obligation, sales or lettings valuation please contact your nearest office Stanmore Office: Bushey Office: Tel: 020 8954 8244 Tel: 020 8950 5777 83 Uxbridge Road, Stanmore, HA7 3NH 63 High Road, Bushey, WD23 1EE V2 ViSIOnStanmoreEdgware edition3 | to advertise call 01442 254894 ViSIOnStanmoreEdgware edition3 | to advertise call 01442 254894 V3 100 95 75 25 5 0 ParkersFeb14 13 February 2014 15:17:39 6 HISTORY V Editor’s 11 FOOD & DRINK CONTENTS 14 FASHION notes... 15 BEAUTY Hello and welcome to the third 18 HOLLY WILLOUGHBY edition of VISION Stanmore & Edgware lifestyle magazine. 19 TRAVEL The magazine is really starting to take off now, 21 KIDS with lots of suggestions from readers and more 22 CAROLINE AHERNE Misha Mistry, Design Editor exciting content to bring you this month. 23 LOCAL NEWS Despite the frequent rain showers, the summer holidays are finally here, so we have everything you need to survive 32 JOANNA LUMLEY the next six weeks…from fun family activities, to top tips to survive those long train, plane or car journeys with 35 BUSINESS & FINANCE the kids. Mum of three, Holly Willoughby even shares her wisdom, following the release of her own parenting book. 40 GARDENING We pay tribute to ‘The Greatest’, Muhammad Ali, and relive his most talked about moments, alongside the 41 MUHAMMAD ALI impression he left on the world. -

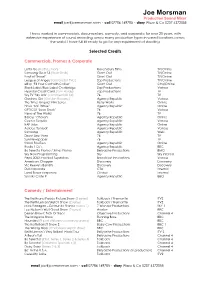

Joe Morsman Production Sound Mixer Email [email protected] • Call 07786 169785 • Diary Wizzo & Co 0207 4372055

Joe Morsman Production Sound Mixer email [email protected] • call 07786 169785 • diary Wizzo & Co 0207 4372055 I have worked in commercials, documentary, comedy, and corporate for over 20 years, with extensive experience of sound recording across many production types in varied locations across the world. I have full kit ready to go for any requirement of shooting. Selected Credits Commercials, Promos & Corporate Lotto Go (Keith Lemon) Ravensbury Films TV/Online Samsung Gear S3 (Bear Grylls) Giant Owl TV/Online PayPal ‘Travel’ Giant Owl TV/Online League of Angels (Gal Gadot TVC) Zap Productions TV/Online eBay ‘Fill Your Cart with Colour’ Giant Owl CH4/Online Black Label/Blue Label Crestbridge Zap Productions Various Hyundai Credit Card (Tom Hardy) Zap Productions TV Sky TV ‘Sky Arts’ (commercials X4) 76 TV Gordons Gin (Gordon Ramsey) Agency Republic Various The Times Unquiet Film Series Betsy Works Online Hovis ‘Soft White’ Agency Republic Online OFT/COI ‘Loan Shark’ 76 Various News of The World 76 TV Baileys ‘Chosen’ Agency Republic Online Cuervo Tequila Agency Republic Various RAF Jobs Agency Republic Online Adidas ‘Symbol’ Agency Republic Various Samsung Agency Republic Web Direct Line Vans 76 TV Sun Newspaper 76 TV Smart FourTwo Agency Republic Online Radio 1 DJ’s Agency Republic BBC Bo Selecta Promo / Xmas Promo Bellyache Productions BMG Sky New Programming Sky Sky internal Pepsi 2002: Football Superstars Broadcast Innovations Various American Chopper Discovery Discovery Vic Reeve’s Bandits Discovery Discovery EMI corporate CTA -

Download Two Greedy Italians Eat Italy, Antonio Carluccio, Gennaro

Two Greedy Italians Eat Italy, Antonio Carluccio, Gennaro Contaldo, Quadrille Publishing, Limited, 2012, 1849491097, 9781849491099, . Antonio Carluccio and Gennaro Contaldo embark on a journey to explore Italy's distinct and varied terrains, and to find out how these have shaped the produce and, in turn, the peoples and their traditions.. DOWNLOAD HERE Table for Two French Recipes for Romantic Dining, Marianne Paquin, Jan 5, 2010, , 240 pages. An accomplished French cook offers 80 classic recipes to be prepared or tasted as a couple. "The love of food, when it is shared, is conducive to a blissful love life .... Gifts from the Garden 100 Gorgeous Homegrown Presents, Debora Robertson, Jun 16, 2013, Cooking, 176 pages. A collection of projects--such as chamomile bubble bath and scented room spray--using plants and produce that can be easily grown in your garden.. Antonio Carluccio's Simple Cooking , Antonio Carluccio, Sep 1, 2009, , 176 pages. Antonio Carluccio Goes Wild 120 Recipes for Wild Food from Land and Sea, Antonio Carluccio, Feb 1, 2002, , 224 pages. Antonio Carluccio Goes Wild is the natural successor to his best-selling Passion for Mushrooms. Here, Antonio revels in the natural bounty of the woods, fields, and seashore .... Keep Calm Cast on Good Advice for Knitters, Erika Knight, Dec 1, 2011, , 191 pages. Gennaro's Italian Year , Gennaro Contaldo, Sep 1, 2009, , 264 pages. As much a celebration of Italy as its food, Gennaro's Italian Year brings this beautiful country vibrantly to life. From feast days to festivals, Christmas delicacies to .... Family Italian , Gennaro Contaldo, Sep 3, 2013, Cooking, 240 pages.