Abraham Akau Kualoa Ranch, O`Ahu

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hakuin on Kensho: the Four Ways of Knowing/Edited with Commentary by Albert Low.—1St Ed

ABOUT THE BOOK Kensho is the Zen experience of waking up to one’s own true nature—of understanding oneself to be not different from the Buddha-nature that pervades all existence. The Japanese Zen Master Hakuin (1689–1769) considered the experience to be essential. In his autobiography he says: “Anyone who would call himself a member of the Zen family must first achieve kensho- realization of the Buddha’s way. If a person who has not achieved kensho says he is a follower of Zen, he is an outrageous fraud. A swindler pure and simple.” Hakuin’s short text on kensho, “Four Ways of Knowing of an Awakened Person,” is a little-known Zen classic. The “four ways” he describes include the way of knowing of the Great Perfect Mirror, the way of knowing equality, the way of knowing by differentiation, and the way of the perfection of action. Rather than simply being methods for “checking” for enlightenment in oneself, these ways ultimately exemplify Zen practice. Albert Low has provided careful, line-by-line commentary for the text that illuminates its profound wisdom and makes it an inspiration for deeper spiritual practice. ALBERT LOW holds degrees in philosophy and psychology, and was for many years a management consultant, lecturing widely on organizational dynamics. He studied Zen under Roshi Philip Kapleau, author of The Three Pillars of Zen, receiving transmission as a teacher in 1986. He is currently director and guiding teacher of the Montreal Zen Centre. He is the author of several books, including Zen and Creative Management and The Iron Cow of Zen. -

Racial Justice in Engineering the Road Ahead for Mckelvey Engineering

mckelvey engineering Across Disciplines. Across the World® // spring 2021 Racial justice in Engineering The road ahead for McKelvey Engineering inside Neal Patwari 18 // Virtual becomes reality 22 // Libby Allman 26 From the dean // The Long Road Ahead I write this letter as we are wrapping up what will be remembered as the most unusual academic year in living memory. The COVID-19 pandemic, which last spring was a crisis requiring an immediate response to launch online learning, grew into an ever-present constraint that impacted teaching, research and all aspects of operations across the university. For the Fall 2020 and Spring 2021 semesters, McKelvey Engineering needed to embrace new paradigms of teaching and learning, to develop new modes of managing and sharing research spaces, and to conduct business operations almost exclusively through remote interactions. In the pages of this issue of Engineering Momentum, you will read about some of the efforts it took to rise to the occasion. Given the enormity of the task, one might expect responding to COVID-19 to be the cover story of this issue of the magazine. It is not. Instead, the summer of last year saw the emergence of an awareness of a challenge that has been with us for centuries and whose destructive power is not amenable to being controlled by a vaccine. While the most visible event of the summer was the video-captured death of George Floyd at the hands of police officers, there was a washu photo litany of such tragedies and travesties. These incidents energized a Black Lives Matter Aaron F. -

When You Reach Me but You Will Get the Job Done

OceanofPDF.com 2 Table of Contents Things You Keep in a Box Things That Go Missing Things You Hide The Speed Round Things That Kick Things That Get Tangled Things That Stain Mom’s Rules for Life in New York City Things You Wish For Things That Sneak Up on You Things That Bounce Things That Burn The Winner’s Circle Things You Keep Secret Things That Smell Things You Don’t Forget The First Note Things on a Slant White Things The Second Note Things You Push Away Things You Count Messy Things Invisible Things Things You Hold On To Salty Things Things You Pretend Things That Crack Things Left Behind The Third Note Things That Make No Sense The First Proof Things You Give Away Things That Get Stuck Tied-Up Things Things That Turn Pink Things That Fall Apart 3 Christmas Vacation The Second Proof Things in an Elevator Things You Realize Things You Beg For Things That Turn Upside Down Things That Are Sweet The Last Note Difficult Things Things That Heal Things You Protect Things You Line Up The $20,000 Pyramid Magic Thread Things That Open Things That Blow Away Sal and Miranda, Miranda and Sal Parting Gifts Acknowledgments About the Author 4 To Sean, Jack, and Eli, champions of inappropriate laughter, fierce love, and extremely deep questions 5 The most beautiful experience we can have is the mysterious. —Albert Einstein The World, As I See It (1931) 6 Things You Keep in a Box So Mom got the postcard today. It says Congratulations in big curly letters, and at the very top is the address of Studio TV-15 on West 58th Street. -

Small Mentor-Protege Program

File Name: 0802181551_080118-807313-SBA-FY2018First [START OF TRANSCRIPT] Carla: Ladies and gentlemen, welcome and thank you for joining today's live SBA web conference. Please note that all participant lines will be muted for the duration of this event. You are welcome to submit written questions during the presentation and these will be addressed during Q&A. To submit a written question, please use the chat panel on the right-hand side of your screen. Choose all panelists from the Send To drop down menu. If you require technical assistance, please send a private note to the event producer. I would now like to formally begin today's conference and introduce Chris Eischen. Chris, please go ahead. Chris: Thank you Carla. Hello everyone and welcome to SBA's First Wednesday webinar series. For today's session, we'll be focusing on the All Small Mentor Protégée Program, and by the end of the program you should have a better understanding of this topic as well as the resources available to you. If you are new to our event, this is a webinar series that focuses on getting subject matter experts on specific small business programs, in this case, All Small Mentor Protégée Program, and having them provide you with valuable information you can use in the performance of your job as an SBA employee, a member of the Federal acquisition community, or a PTAC employee. We appreciate you taking this time to join us on the August edition of SBA's First Wednesday webinar series, and we hope that you benefit from today's session. -

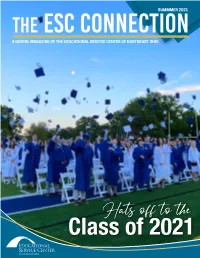

Hats Off to the Class of 2021

SUMMMER 2021 THE ESC CONNECTION A DIGITAL MAGAZINE OF THE EDUCATIONAL SERVICE CENTER OF NORTHEAST OHIO Hats off to the Class of 2021 Educational Service Center (ESC) of Northeast Ohio 1 6393 Oak Tree Blvd. Independence, OH 44131 (216) 524-3000 Fax (216) 524-3683 Superintendent’s Robert A. Mengerink Superintendent message Jennifer Dodd Director of Operations and Development By Dr. Bob Mengerink, Superintendent Steve Rogaski Director of Pupil Services Dear Colleagues, Bruce G. Basalla Treasurer As you all begin your summer, I hope you are all able to reflect on this past school year and find some positive aspects of the challenges you faced. This may be the new skills you have learned in technology or creative ways of expanding learning options for students. It could be the reminder of how GOVERNING BOARD we can and should lean on colleagues for support. Perhaps it is a greater Christine Krol President appreciation for understanding and addressing the non-academic needs of students. It might be realizing how adaptable we really are at accepting Anthony Miceli changes. Or maybe it’s remembering to slow down and prioritize what is Vice President most important for our students, ourselves and our families. Whatever it is, Carol Fortlage you should all be proud of how you have taken these challenges, led with Tony Hocevar grace and continuously identified solutions for your students, parents and Frank Mahnic, Jr. community. While there will always be challenges and controversy ahead in leading and transforming schools, my sincerest wish for you this summer is Editor: to do those things that will allow you to recharge yourself both physically and Nadine Grimm mentally while remembering that you are truly our unsung heroes. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD—SENATE, Vol. 154, Pt. 2

February 12, 2008 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD—SENATE, Vol. 154, Pt. 2 1933 the challenges of our time? Those are terrible costs of America’s revolution a profound personal commitment to the discussions the Abraham Lincoln could always be seen—in Lincoln’s human rights. We will remember not Bicentennial Commission hopes to fos- words—‘‘in the form of a husband, a fa- only his courage and his optimism, but ter as America prepares to celebrate ther, a son or a brother. A living also his deep affection for his adopted the bicentennial of the birth of its history was to be found in every family country. He leaves behind a legacy of greatest President. in the limbs mangled, [and] in the hope and inspiration. I encourage everyone to go to the scars of wounds received . ’’ On a personal level, it was an honor Commission’s Web site at Lincoln went on to say: to call TOM a colleague and a friend. I www.lincolnbicentennial.com, learn But those histories are gone. They were was proud to work with him on so more about Lincoln and about how the pillars of liberty; and now that they have many important issues. your community can plan to celebrate crumbled away, that temple must fall—un- I remember working with him to se- his birthday. President Lincoln’s less we, their descendants, supply their place cure funding to build a tunnel to by- adopted hometown of Springfield is with other pillars. pass a section of Route 1 that was so also my adopted hometown. I have I would like to think that Lincoln frequently closed by landslides that it lived there almost 40 years now. -

Whittaker, Jim RFK #1

Jim Whittaker Oral History Interview –RFK #1, 4/25/1969 Administrative Information Creator: Jim Whittaker Interviewer: Roberta W. Greene Date of Interview: April 25, 1969 Place of Interview: Hickory Hill, McLean, Virginia Length: 21 pp. Biographical Note Whittaker, Jim; Friend, associate, Robert F. Kennedy, 1965-1968; expedition leader, National Geographic climb, Mt. Kennedy, Yukon, Canada, 1965; campaign worker, Robert F. Kennedy for President, 1968. Whittaker discusses the climb he led up Mount Kennedy which included Senator Robert F. Kennedy [RFK], the formation of their relationship due to this trip, and his thoughts on RFK’s personality, among other issues. Access Restrictions No restrictions. Usage Restrictions According to the deed of gift signed January 8, 1991, copyright of these materials has been assigned to the United States Government. Users of these materials are advised to determine the copyright status of any document from which they wish to publish. Copyright The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be “used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research.” If a user makes a request for, or later uses, a photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excesses of “fair use,” that user may be liable for copyright infringement. This institution reserves the right to refuse to accept a copying order if, in its judgment, fulfillment of the order would involve violation of copyright law. -

Finance Committee

05/08/2006 Finance 1 COMMITTEE ON FINANCE May 8, 2006 6:00 PM Vice-Chairman Gatsas called the meeting to order. Vice-Chairman Gatsas called for the Pledge of Allegiance, this function being led by Alderman Roy. A moment of silent prayer was observed. The Clerk called the roll. There were twelve Aldermen present. Present: Aldermen Roy, Gatsas, Long, Duval, Osborne, Pinard, Lopez, Shea, DeVries, Smith, Thibault and Forest Absent: Aldermen O’Neil and Garrity Messrs.: David Cornell, Tom Nichols, Stephan Hamilton, Jim Hoben, Denise Boutilier, Kevin Clougherty, Randy Sherman, Virginia Lamberton Vice-Chairman Gatsas advises that the purpose of the meeting shall be continuing discussions relating to the proposed FY2007 municipal budget and we’ll just change a little bit of the order and apologize but there are some people that had some commitments and have the Assessors go first followed by Traffic and then Finance. Board of Assessors Mr. David Cornell, Chairman of the Board of Assessors, stated today we will be presenting information on the exemption analysis giving an update of exactly where we’re at with our 2006 projected tax base. Historically the Mayor and Board of Aldermen have adjusted the exemption amounts during reval years. Our goal in this process is to provide the Mayor and the Aldermen with as much factual information so they can make an informed decision on this very important topic. Certainly we feel our role in this process is advisory in nature and some of the figures that we’ve provided to you aren’t necessarily our recommendations but they’re the figures that need to be adjusted to if the goal of the Aldermen is to keep the same proportional benefit before the reval and after the reval. -

The Wonders of the Invisible World. Observations As Well Historical As Theological, Upon the Nature, the Number, and the Operations of the Devils (1693)

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Electronic Texts in American Studies Libraries at University of Nebraska-Lincoln 1693 The Wonders of the Invisible World. Observations as Well Historical as Theological, upon the Nature, the Number, and the Operations of the Devils (1693) Cotton Mather Second Church (Congregational), Boston Reiner Smolinski , Editor Georgia State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/etas Part of the American Studies Commons Mather, Cotton and Smolinski, Reiner , Editor, "The Wonders of the Invisible World. Observations as Well Historical as Theological, upon the Nature, the Number, and the Operations of the Devils (1693)" (1693). Electronic Texts in American Studies. 19. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/etas/19 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Libraries at University of Nebraska-Lincoln at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Texts in American Studies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. The Wonders of the Invisible World: COTTON MATHER (1662/3–1727/8). The eldest son of New England’s leading divine, Increase Mather and grand- Observations as Well Historical as Theological, son of the colony’s spiritual founders Richard Mather and John Cotton, Mather was born in Boston, educated at Har- upon the Nature, the Number, and the vard (B. A. 1678; M. A. 1681), and received an honorary Doctor of Divinity degree from Glasgow University (1710). Operations of the Devils As pastor of Boston’s Second Church (Congregational), he came into the political limelight during America’s version [1693] of the Glorious Revolution, when Bostonians deposed their royal governor, Sir Edmund Andros (April 1689). -

Idioms-And-Expressions.Pdf

Idioms and Expressions by David Holmes A method for learning and remembering idioms and expressions I wrote this model as a teaching device during the time I was working in Bangkok, Thai- land, as a legal editor and language consultant, with one of the Big Four Legal and Tax companies, KPMG (during my afternoon job) after teaching at the university. When I had no legal documents to edit and no individual advising to do (which was quite frequently) I would sit at my desk, (like some old character out of a Charles Dickens’ novel) and prepare language materials to be used for helping professionals who had learned English as a second language—for even up to fifteen years in school—but who were still unable to follow a movie in English, understand the World News on TV, or converse in a colloquial style, because they’d never had a chance to hear and learn com- mon, everyday expressions such as, “It’s a done deal!” or “Drop whatever you’re doing.” Because misunderstandings of such idioms and expressions frequently caused miscom- munication between our management teams and foreign clients, I was asked to try to as- sist. I am happy to be able to share the materials that follow, such as they are, in the hope that they may be of some use and benefit to others. The simple teaching device I used was three-fold: 1. Make a note of an idiom/expression 2. Define and explain it in understandable words (including synonyms.) 3. Give at least three sample sentences to illustrate how the expression is used in context. -

Stories of Minjung Theology

International Voices in Biblical Studies STORIES OF MINJUNG THEOLOGY STORIES This translation of Asian theologian Ahn Byung-Mu’s autobiography combines his personal story with the history of the Korean nation in light of the dramatic social, political, and cultural upheavals of the STORIES OF 1970s. The book records the history of minjung (the people’s) theology that emerged in Asia and Ahn’s involvement in it. Conversations MINJUNG THEOLOGY between Ahn and his students reveal his interpretations of major Christian doctrines such as God, sin, Jesus, and the Holy Spirit from The Theological Journey of Ahn Byung‑Mu the minjung perspective. The volume also contains an introductory essay that situates Ahn’s work in its context and discusses the place in His Own Words and purpose of minjung hermeneutics in a vastly different Korea. (1922–1996) was professor at Hanshin University, South Korea, and one of the pioneers of minjung theology. He was imprisonedAHN BYUNG-MU twice for his political views by the Korean military government. He published more than twenty books and contributed more than a thousand articles and essays in Korean. His extended work in English is Jesus of Galilee (2004). In/Park Electronic open access edition (ISBN 978-0-88414-410-6) available at http://ivbs.sbl-site.org/home.aspx Translated and edited by Hanna In and Wongi Park STORIES OF MINJUNG THEOLOGY INTERNATIONAL VOICES IN BIBLICAL STUDIES Jione Havea, General Editor Editorial Board: Jin Young Choi Musa W. Dube David Joy Aliou C. Niang Nasili Vaka’uta Gerald O. West Number 11 STORIES OF MINJUNG THEOLOGY The Theological Journey of Ahn Byung-Mu in His Own Words Translated by Hanna In. -

About Autism Script

Slide 1. What will I learn in this Autism Navigator tool? Welcome to Autism Navigator, a unique collection of web-based tools that uses extensive video footage to bridge the gap between science and community practice. You will have the opportunity to explore three topics about autism. You will learn about: • the core diagnostic features of autism, • the critical importance of early detection and early intervention, and • current information on prevalence and causes of autism. You will also have the opportunity to access some of the innovative features of Autism Navigator. A slide index is located on the left side of the bottom toolbar. A slide viewer is located on the right side of the bottom toolbar. These can be used to navigate easily to specific slides. For a self-guided tour to learn how to navigate Autism Navigator and for tech support, go to Help in the top bar. What are the diagnostic features of autism? Slide 2. Video: How is autism impacting us now? Child: Gingerbread houses…Cornucopia… Autism can be obvious or subtle. A child who can read by three, but can’t play peak-a-boo… Child: Macadamia pineapple tart… One who knows everything about trains and dinosaurs and gets upset if you ask about anything else. One who may never utter a spoken word, but rather use pictures or signing to be understood. The signs are as varied as the number of children affected. It affects all children. Boys 4 times more often than girls. There is no known biological marker or medical test to help diagnose it.