THE POINT WHERE THEY MEET and OTHER STORIES a Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gordon Ramsay Uncharted

SPECIAL PROMOTION SIX DESTINATIONS ONE CHEF “This stuff deserves to sit on the best tables of the world.” – GORDON RAMSAY; CHEF, STUDENT AND EXPLORER SPECIAL PROMOTION THIS MAGAZINE WAS PRODUCED BY NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC CHANNEL IN PROMOTION OF THE SERIES GORDON RAMSAY: CONTENTS UNCHARTED PREMIERES SUNDAY JULY 21 10/9c FEATURE EMBARK EXPLORE WHERE IN 10THE WORLD is Gordon Ramsay cooking tonight? 18 UNCHARTED TRAVEL BITES We’ve collected travel stories and recipes LAOS inspired by Gordon’s (L to R) Yuta, Gordon culinary journey so that and Mr. Ten take you can embark on a spin on Mr. Ten’s your own. Bon appetit! souped-up ride. TRAVEL SERIES GORDON RAMSAY: ALASKA Discover 10 Secrets of UNCHARTED Glacial ice harvester Machu Picchu In his new series, Michelle Costello Gordon Ramsay mixes a Manhattan 10 Reasons to travels to six global with Gordon using ice Visit New Zealand destinations to learn they’ve just harvested from the locals. In from Tracy Arm Fjord 4THE PATH TO Go Inside the Labyrin- New Zealand, Peru, in Alaska. UNCHARTED thine Medina of Fez Morocco, Laos, Hawaii A rare look at Gordon and Alaska, he explores Ramsay as you’ve never Road Trip: Maui the culture, traditions seen him before. and cuisine the way See the Rich Spiritual and only he can — with PHOTOS LEFT TO RIGHT: ERNESTO BENAVIDES, Cultural Traditions of Laos some heart-pumping JON KROLL, MARK JOHNSON, adventure on the side. MARK EDWARD HARRIS Discover the DESIGN BY: Best of Anchorage MARY DUNNINGTON 2 GORDON RAMSAY: UNCHARTED SPECIAL PROMOTION 3 BY JILL K. -

Felix Issue 0985, 1994

loo<tF The Student Newspaper of Imperiaiperiall ColleqCollegee I 3DRI8B3iaCE||olrj g 210CT94 TCCB-tSCTIONj enamings benefits of the proposal had not. ANDREW DORMAN-SMITH been adequately debated. Professor Shaw said the name of Senior academics at. the. the Department itself does not Department, of Mineral Resources overly matter, and said he was, Engineering (MRE) have called "a believer in tradition". Professor for further discussions over a plan Shaw would not say if he sup- to rename the department. Earth ported the name change proposal. Resources Engineering has However, the new head of emerged as the favourite choice MRE, and Dean of the newly for a new name, after discussions established Graduate School of between college officials. the Environment, Professor The change has been mooted Woods, is believed to think the following a letter from the proposal is a 'great idea'. His role Professor John Archer, Pro- as Dean will be to coordinate the Rector, which asks for comments departments of Imperial, and to on the new title. Professor Archer, present the benefits for research said that he has received only one of the college in line with a review negative response to his letter, completed in May by Sir John and claimed that most of the Mason. department's staff agree with the The other two RSM depart- proposal. But Professor Archer ments may also change names. said discussions are continuing - The college's chief decision mak- despite the publication of an offi- ing body, the Management cial college note which says the Finnish Embassy Planning Group (MPG), has sug- Photo by Ivan Chan change will take place "shortly". -

When You Reach Me but You Will Get the Job Done

OceanofPDF.com 2 Table of Contents Things You Keep in a Box Things That Go Missing Things You Hide The Speed Round Things That Kick Things That Get Tangled Things That Stain Mom’s Rules for Life in New York City Things You Wish For Things That Sneak Up on You Things That Bounce Things That Burn The Winner’s Circle Things You Keep Secret Things That Smell Things You Don’t Forget The First Note Things on a Slant White Things The Second Note Things You Push Away Things You Count Messy Things Invisible Things Things You Hold On To Salty Things Things You Pretend Things That Crack Things Left Behind The Third Note Things That Make No Sense The First Proof Things You Give Away Things That Get Stuck Tied-Up Things Things That Turn Pink Things That Fall Apart 3 Christmas Vacation The Second Proof Things in an Elevator Things You Realize Things You Beg For Things That Turn Upside Down Things That Are Sweet The Last Note Difficult Things Things That Heal Things You Protect Things You Line Up The $20,000 Pyramid Magic Thread Things That Open Things That Blow Away Sal and Miranda, Miranda and Sal Parting Gifts Acknowledgments About the Author 4 To Sean, Jack, and Eli, champions of inappropriate laughter, fierce love, and extremely deep questions 5 The most beautiful experience we can have is the mysterious. —Albert Einstein The World, As I See It (1931) 6 Things You Keep in a Box So Mom got the postcard today. It says Congratulations in big curly letters, and at the very top is the address of Studio TV-15 on West 58th Street. -

Small Mentor-Protege Program

File Name: 0802181551_080118-807313-SBA-FY2018First [START OF TRANSCRIPT] Carla: Ladies and gentlemen, welcome and thank you for joining today's live SBA web conference. Please note that all participant lines will be muted for the duration of this event. You are welcome to submit written questions during the presentation and these will be addressed during Q&A. To submit a written question, please use the chat panel on the right-hand side of your screen. Choose all panelists from the Send To drop down menu. If you require technical assistance, please send a private note to the event producer. I would now like to formally begin today's conference and introduce Chris Eischen. Chris, please go ahead. Chris: Thank you Carla. Hello everyone and welcome to SBA's First Wednesday webinar series. For today's session, we'll be focusing on the All Small Mentor Protégée Program, and by the end of the program you should have a better understanding of this topic as well as the resources available to you. If you are new to our event, this is a webinar series that focuses on getting subject matter experts on specific small business programs, in this case, All Small Mentor Protégée Program, and having them provide you with valuable information you can use in the performance of your job as an SBA employee, a member of the Federal acquisition community, or a PTAC employee. We appreciate you taking this time to join us on the August edition of SBA's First Wednesday webinar series, and we hope that you benefit from today's session. -

The Life & Rhymes of Jay-Z, an Historical Biography

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: THE LIFE & RHYMES OF JAY-Z, AN HISTORICAL BIOGRAPHY: 1969-2004 Omékongo Dibinga, Doctor of Philosophy, 2015 Dissertation directed by: Dr. Barbara Finkelstein, Professor Emerita, University of Maryland College of Education. Department of Teaching and Learning, Policy and Leadership. The purpose of this dissertation is to explore the life and ideas of Jay-Z. It is an effort to illuminate the ways in which he managed the vicissitudes of life as they were inscribed in the political, economic cultural, social contexts and message systems of the worlds which he inhabited: the social ideas of class struggle, the fact of black youth disempowerment, educational disenfranchisement, entrepreneurial possibility, and the struggle of families to buffer their children from the horrors of life on the streets. Jay-Z was born into a society in flux in 1969. By the time Jay-Z reached his 20s, he saw the art form he came to love at the age of 9—hip hop— become a vehicle for upward mobility and the acquisition of great wealth through the sale of multiplatinum albums, massive record deal signings, and the omnipresence of hip-hop culture on radio and television. In short, Jay-Z lived at a time where, if he could survive his turbulent environment, he could take advantage of new terrains of possibility. This dissertation seeks to shed light on the life and development of Jay-Z during a time of great challenge and change in America and beyond. THE LIFE & RHYMES OF JAY-Z, AN HISTORICAL BIOGRAPHY: 1969-2004 An historical biography: 1969-2004 by Omékongo Dibinga Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2015 Advisory Committee: Professor Barbara Finkelstein, Chair Professor Steve Klees Professor Robert Croninger Professor Derrick Alridge Professor Hoda Mahmoudi © Copyright by Omékongo Dibinga 2015 Acknowledgments I would first like to thank God for making life possible and bringing me to this point in my life. -

Beverly Hills

briefs • City to subsidize $1.6 million briefs • City refuses to declare rudy cole • My recommendations loan for City Manager housing Page 3 opinion on subway route Page 4 for state office Page 6 ALSO ON THE WEB Beverly Hills www.bhweekly.com WeeklySERVING BEVERLY HILLS • BEVERLYWOOD • LOS ANGELES Issue 575 • October 7 - October 13, 2010 OUR 11th Beverly Hills’ Anniversary First Lady The Weekly’s interview with Lonnie Delshad cover story • pages 8-9 Few motorists would risk their lives by for anyone but a Democrat because it would briefs • Lively subway route hearing at briefs • Julian Gold announces rudy cole • Roxbury Park Page 2 candidacy for City Council Page 3 United city speaks Page 6 bicycle community in the region, and isn’t have disappointed his liberal mother. As ALSO ON THE WEB Beverly Hills www.bhweekly.com that part of our transportation problem? Too one of my favorite commentators, Dennis letters too few folks using alternate transportation Prager, pointed out in a recent article, so WeeklySERVING BEVERLY HILLS • BEVERLYWOOD • LOS ANGELES means too many cars on the road. Bike- many registered Democrats vote for Left- Issue 574 • September 30 - October 6, 2010 friendly infrastructure not only protects wing candidates who do not share their Beverly High Athletic cyclists entitled to ride all of the streets in views for purely emotional, nonsensical Alumni to be inducted & email our city, but it reduces motorist liability too. reasons. In Rudy’s case, it is because his Simply put, bikes belong, so let’s plan for mother would disapprove of him voting into Hall of Fame them to accommodate bikes safely. -

Hats Off to the Class of 2021

SUMMMER 2021 THE ESC CONNECTION A DIGITAL MAGAZINE OF THE EDUCATIONAL SERVICE CENTER OF NORTHEAST OHIO Hats off to the Class of 2021 Educational Service Center (ESC) of Northeast Ohio 1 6393 Oak Tree Blvd. Independence, OH 44131 (216) 524-3000 Fax (216) 524-3683 Superintendent’s Robert A. Mengerink Superintendent message Jennifer Dodd Director of Operations and Development By Dr. Bob Mengerink, Superintendent Steve Rogaski Director of Pupil Services Dear Colleagues, Bruce G. Basalla Treasurer As you all begin your summer, I hope you are all able to reflect on this past school year and find some positive aspects of the challenges you faced. This may be the new skills you have learned in technology or creative ways of expanding learning options for students. It could be the reminder of how GOVERNING BOARD we can and should lean on colleagues for support. Perhaps it is a greater Christine Krol President appreciation for understanding and addressing the non-academic needs of students. It might be realizing how adaptable we really are at accepting Anthony Miceli changes. Or maybe it’s remembering to slow down and prioritize what is Vice President most important for our students, ourselves and our families. Whatever it is, Carol Fortlage you should all be proud of how you have taken these challenges, led with Tony Hocevar grace and continuously identified solutions for your students, parents and Frank Mahnic, Jr. community. While there will always be challenges and controversy ahead in leading and transforming schools, my sincerest wish for you this summer is Editor: to do those things that will allow you to recharge yourself both physically and Nadine Grimm mentally while remembering that you are truly our unsung heroes. -

Celebration Schedule 2012 Provost's Office Gettysburg College

Celebration Celebration 2012 May 5th, 9:00 AM - 5:00 PM Celebration Schedule 2012 Provost's Office Gettysburg College Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/celebration Part of the Higher Education Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Provost's Office, "Celebration Schedule 2012" (2012). Celebration. 55. https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/celebration/2012/Panels/55 This open access event is brought to you by The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The uC pola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Description Full presentation schedule for Celebration, May 5, 2012 Location Gettysburg College Disciplines Higher Education This event is available at The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/celebration/2012/Panels/55 From the Provost I am most pleased to welcome you to Gettysburg College’s Fourth Annual Colloquium on Undergraduate Research, Creative Activity, and Community Engagement. Today is truly a cause for celebration, as our students present the results of the great work they’ve been engaged in during the past year. Students representing all four class years and from across the disciplines are demonstrating today what’s best about the Gettysburg College experience— intentional collaborations between students and their mentors such that students acquire both knowledge and skills that can be applied to many facets of their future personal and professional lives. The benefits for those who mentor these young adults may, at first, be more difficult to discern. Most of those who engage in mentoring do it because they enjoy being around students who are eager to learn what they have to teach them. -

Smash-Hits-1980-12-J

TLY ...,., man League lbums lncolour be won ROXY MUSIC FLESH+BLOOD Phone 01-200 0200 To find out the nearest shop where you can obtain "Flesh & Blood" at a minimwn of £1.00 off tlte album's R.R.P. ALBUM & CASSETTE 1.,.,~.1EiJ NEW AMSTERDAM June 12-25 1980 Elvis Costello ...........................................4 It's tough atthe top. Jerry TIN SOLDIERS Dammers just popped in to Stiff Little Fingers ....................................4 borrow a picture of himself. Seems he was trying to cash a CHRISTINE cheque at the bank and the Siouxsie & The Banshees ....................... 5 people didn't recognise him . .. Our apologies next to the folks CRYING who were disappointed by the Don Mclean .............................................8 absence of the promised Dexy's colour poster in the lastjssue. CHINATOWN r----...:S~ee, thei:O• haef'already been 4 rattled off to the prlntws before THT:~EL~.1oivi. M·~A~s·~·H ........................ ·1 the actual shot arrived and we decided we needed to~ bett.er. The Mash ............................................... 14 have atlence ,and we1t bring LITTLE JEANNIE one soon. This time around eve definitely got a fantastic Elton John .............................................. 16 vid,c> game for our new IF LOVING YOU IS WRONG d prize, our Irresistible lffer OD page 26 plus a Rod Stewart ........................................... 16 S etro"c:ompetition on page • EVERYBODY'S GOTTO LEARN 28. So'-Juat think yourself lucky - we UNd_"to'"1ive7n a _rolled u SOMETIME -~e'.lnidHle ofthe"' The Korgis .............................................. 19 BACK TOGETHER AGAIN Roberta Flack & Donny Hathaway ........22 THE MAN WHO DIES EVERYDAY ntributon Ultravox .................................................29 qb' K'-atz TO BE OR NOT TO BE R~ttrr Fr,cl Deller B. -

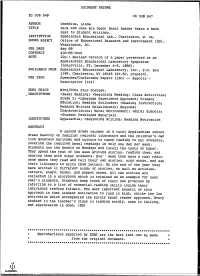

**************************S************************** Reproductions Supplied by EDRS Are the Best Thatcan Be Made from the Original Document

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 306 549 CS 009 647 AUTHOR Oxendine, Linda TITLE Dick and Jane Are Dead: Basal Reader Takes a Back Seat to Student Writings. INSTITUTION Appalachia Educational Lab., Charleston, W. Va. SPONS AGENCY Office of Educational Research and Improvement (ED), Washington, DC. PUB DATE May 89 CONTRACT 400-86-0001 NOTE 22p.; Revised version of a paper presented atan Appalachian Educational Laboratory Symposium (Louisville, KY, December 4-5, 1988). AVAILABLE FROMAppalachia Educational Laboratory, Inc., P.O. Box 1348, Charleston, WV 25325 ($3.50, prepaid). PUB TYPE Speeches/Conference Papers (150)-- Reports - Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Basal Reading; *Beginning Reading; Class Activities; Grade 2; *Language Experience Approach; Primary Education; Reading Attitudes; *Reading Instruction; Reading Writing Relationship; Regional- Characteristics; Rural Environment; *Rural Schools; *Student Developed Materials IDENTIFIERS Appalachia; *Beginning Writing; Reading Motivation ABSTRACT A second grade teacher in a rural Appalachian school draws heavily on familiar regional literature and the children'sown rich mountain heritage and culture to teach reading to herstudents, covering the required basal readings in onlyone day per week. Students use the basals on Mondays and retell the textson paper. They spend the rest of the week writing stories, readingthem, and sharing them with other students. Eve" week they havea real radio show where they read and tell their own stories, singsongs, and ask their listeners to write them letters. By the end of theyear they have written 11 different kinds of stories,as well as articles, letters, plays, books, and puppet shows. All the storiesare collected in a storybook which is retainedas an example for next year's students. -

TARANTULA EPISODE 1.Fdx

SEESAW/MUSHROOM "TARANTULA" EPISODE 1 Written by Carson Mell EXT. TARANTULA - DAY The beautiful, decrepit Tierra Chula Resident Hotel. Early morning light. Echo exits, scratching ribs and sipping coffee, and walks right up to FRANK, a homeless guy sitting on the corner with a “Will Work For Food” sign. ECHO So, uh, that sign. You serious about that or just looking to shake loose a few crumbs from the upper crust? FRANK I’m serious. ECHO You mind if I see you erect. You know, upright. Standing up. The guy stands. He’s remarkably tall and slim, especially beside five-foot-six Echo. Echo whistles through his teeth. ECHO (CONT’D) Yep. That’ll do. EXT. TARANTULA/BACK PATIO - DAY Echo sits on Frank’s shoulders, is deep in the big avocado tree. He plucks an avocado and smells it deeply. ECHO Oh, yeah, that is the bouquet we are looking for. Echo places the avocado in his plastic grocery sack, reaches for another, and accidentally digs a knee into Frank’s side. FRANK Ah God damn! ECHO Sorry man, I know this ain’t exactly comfortable, but we gotta keep it down or my landlord is going to pop out of that window right there and shoot us with a pellet gun. Echo points up high to the window of a penthouse. 2. ECHO (CONT’D) Sir Dominic considers these avocados his sole property. Dude would charge us for each breath we took if he could. Frank looks up at the window. There’s a woman with graying hair sitting in a recliner, hooked up to oxygen. -

Visualizing Levinas:Existence and Existents Through Mulholland Drive

VISUALIZING LEVINAS: EXISTENCE AND EXISTENTS THROUGH MULHOLLAND DRIVE, MEMENTO, AND VANILLA SKY Holly Lynn Baumgartner A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2005 Committee: Ellen Berry, Advisor Kris Blair Don Callen Edward Danziger Graduate Faculty Representative Erin Labbie ii © 2005 Holly Lynn Baumgartner All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Ellen Berry, Advisor This dissertation engages in an intentional analysis of philosopher Emmanuel Levinas’s book Existence and Existents through the reading of three films: Memento (2001), Vanilla Sky (2001), and Mulholland Drive, (2001). The “modes” and other events of being that Levinas associates with the process of consciousness in Existence and Existents, such as fatigue, light, hypostasis, position, sleep, and time, are examined here. Additionally, the most contested spaces in the films, described as a “Waking Dream,” is set into play with Levinas’s work/ The magnification of certain points of entry into Levinas’s philosophy opened up new pathways for thinking about method itself. Philosophically, this dissertation considers the question of how we become subjects, existents who have taken up Existence, and how that process might be revealed in film/ Additionally, the importance of Existence and Existents both on its own merit and to Levinas’s body of work as a whole, especially to his ethical project is underscored. A second set of entry points are explored in the conclusion of this dissertation, in particular how film functions in relation to philosophy, specifically that of Levinas. What kind of critical stance toward film would be an ethical one? Does the very materiality of film, its fracturing of narrative, time, and space, provide an embodied formulation of some of the basic tenets of Levinas’s thinking? Does it create its own philosophy through its format? And finally, analyzing the results of the project yielded far more complicated and unsettling questions than they answered.