Download the European Grouse Short Science Summary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Necklace-Style Radio-Transmitters Are Associated with Changes in Display Vocalizations of Male Greater Sage-Grouse Authors: Marcella R

Necklace-style radio-transmitters are associated with changes in display vocalizations of male greater sage-grouse Authors: Marcella R. Fremgen, Daniel Gibson, Rebecca L. Ehrlich, Alan H. Krakauer, Jennifer S. Forbey, et. al. Source: Wildlife Biology, 2017(SP1) Published By: Nordic Board for Wildlife Research URL: https://doi.org/10.2981/wlb.00236 BioOne Complete (complete.BioOne.org) is a full-text database of 200 subscribed and open-access titles in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Complete website, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/terms-of-use. Usage of BioOne Complete content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non-commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. Downloaded From: https://bioone.org/journals/Wildlife-Biology on 2/11/2019 Terms of Use: https://bioone.org/terms-of-use Wildlife Biology 2017: wlb.00236 doi: 10.2981/wlb.00236 © 2016 The Authors. This is an Open Access article Subject Editor: Olafur Nielsen. Editor-in-Chief: Ilse Storch. Accepted 19 July 2016 Necklace-style radio-transmitters are associated with changes in display vocalizations of male greater sage-grouse Marcella R. Fremgen, Daniel Gibson, Rebecca L. Ehrlich, Alan H. -

Simplified-ORL-2019-5.1-Final.Pdf

The Ornithological Society of the Middle East, the Caucasus and Central Asia (OSME) The OSME Region List of Bird Taxa, Part F: Simplified OSME Region List (SORL) version 5.1 August 2019. (Aligns with ORL 5.1 July 2019) The simplified OSME list of preferred English & scientific names of all taxa recorded in the OSME region derives from the formal OSME Region List (ORL); see www.osme.org. It is not a taxonomic authority, but is intended to be a useful quick reference. It may be helpful in preparing informal checklists or writing articles on birds of the region. The taxonomic sequence & the scientific names in the SORL largely follow the International Ornithological Congress (IOC) List at www.worldbirdnames.org. We have departed from this source when new research has revealed new understanding or when we have decided that other English names are more appropriate for the OSME Region. The English names in the SORL include many informal names as denoted thus '…' in the ORL. The SORL uses subspecific names where useful; eg where diagnosable populations appear to be approaching species status or are species whose subspecies might be elevated to full species (indicated by round brackets in scientific names); for now, we remain neutral on the precise status - species or subspecies - of such taxa. Future research may amend or contradict our presentation of the SORL; such changes will be incorporated in succeeding SORL versions. This checklist was devised and prepared by AbdulRahman al Sirhan, Steve Preddy and Mike Blair on behalf of OSME Council. Please address any queries to [email protected]. -

Birding Abroad Ltd Georgia & the Caucasus

BIRDING ABROAD LTD GEORGIA & THE CAUCASUS - A GATEWAY TO ASIA 22 - 30 APRIL 2021 TOUR OVERVIEW: Strategically positioned between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, Georgia sits at a geographical, cultural and ecological cross-roads where Europe, Russia, Persia and Western Asia collide in the splendours of the Caucasus Mountains. Steeped in ancient history, with diverse and spectacular landscapes and an abundant natural history, the country is very much in vogue as a birding destination. Birding Abroad first visited Georgia in 2011, subsequently guiding groups there in spring 2012 and again in 2013, and a return visit now beckons. This is a country with a complex cultural, political and religious heritage. The first settlers appeared in the 12th century BC, whilst the bygone state of Colchis was home to the Golden Fleece, so eagerly sought by Jason and the Argonauts in early Greek Mythology. Closer to many of our hearts, the earliest evidence of wine production comes from Georgia, where amazingly, some 8000-year old wine jars have recently been uncovered. Many households still make their own wine in the old-fashioned way. Georgia’s past is never far away. Its most notorious native son Joseph Stalin, was born to poverty in Gori, 45 minutes west of Tbilisi, his impoverished home now housing a small museum. In 1991 as the Soviet Union was collapsing, Georgia declared its independence, and today is building a stable, modern and outward facing nation, fiercely proud of its own identity heritage. Bounded to the north by Russia and to the south and east by Armenia and Azerbaijan, Georgia is a country of exceptional beauty, hosting some of the most dramatic mountain landscapes in the World. -

BIRDS AS FOOD Anthropological and Cross-Disciplinary Perspectives

BIRDS AS FOOD Anthropological and Cross-disciplinary Perspectives edited by Frédéric Duhart and Helen Macbeth Published by the International Commission on the Anthropology of Food and Nutrition BIRDS AS FOOD: Anthropological and Cross-disciplinary Perspectives BIRDS AS FOOD: Anthropological and Cross-disciplinary Perspectives edited by Frédéric Duhart and Helen Macbeth First published in 2018 in the ‘ICAF Alimenta Populorum’ series (Series Editor: Paul Collinson) by the International Commission on the Anthropology of Food and Nutrition (ICAF) © 2018 The International Commission on the Anthropology of Food and Nutrition All rights reserved. Except for downloading the book for personal use or for the quotation of short passages, no part nor total of this electronic publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including printing, photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without the written permission of the International Commission on the Anthropology of Food and Nutrition (ICAF), as agreed jointly by ICAF’s President, General Secretary and Treasurer. The website of ICAF is www.icafood.eu British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Birds as Food: Anthropological and Cross-Disciplinary Perspectives Edited by Frédéric Duhart and Helen Macbeth Size: ix + 328 pages, circa 15 MB Includes bibliographic references, 161 illustrations and 2 indices ISBN 978-0-9500513-0-7 Keywords : Food – Birds; Food – Social aspects; Food – Cultural diversity; Food – Poultry; Ornithology – Human food. LIST OF CONTENTS Page Preface vii List of Contributors viii Introduction 1 A Feathered Feast by Frédéric Duhart and Helen Macbeth 3 Section One: Birds and Humans 15 Chapter 1. -

Grouse News 38 Newsletter of the Grouse Group

GROUSE NEWS Newsletter of the Grouse Group of the IUCN/SSC-WPA Galliformes Specialist Group Issue 38 November 2009 Contents From the chair 2 Conservation News 2009-10 Scottish capercaillie survey 3 Gunnison sage grouse reconsidered 4 Research Reports Inter-specific aggression between red grouse, ptarmigan and pheasant 5 Ecology and conservation of the Cantabrian capercaillie inhabiting Mediterranean Pyrenean oak 7 forests. A new Ph. D. project The long-term evolution of the Cantabrian landscapes and its possible role in the capercaillie 9 drama Estimating the stage of incubation for nests of greater prairie-chickens using egg flotation: a float 12 curve for grousers Status of Missouri greater prairie-chicken populations and preliminary observations from ongoing 15 translocations and monitoring Estimating greater sage-grouse fence collision rates in breeding areas: preliminary results 24 The reintroduced population of capercaillie in the Parc National des Cévennes is still alive 29 Does predation affect lekking behaviour in grouse? A summary of field observations 30 Capercaillie Tetrao urogallus in Serbia – principal threats and conservation measures 32 Black grouse in Perthshire 34 Conferences The Per Wegge Jubilee Symposium 37 The 25th International Ornithological Congress in Brazil 39 Proceedings of the 4th Black Grouse Conference in Vienna 40 The 5th European Black Grouse Conference in Poland 40 Snippets New International Journal of Galliformes Conservation. 42 In memory of Simon Thirgood. 42 Grouse News 38 Newsletter of the Grouse Group From the chair Dear Grousers The latest update of the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species has just been released. It shows that 17,291 species out of the 47,677 assessed species are threatened with extinction. -

Lyrurus Mlokosiewiczi -- (Taczanowski, 1875)

Lyrurus mlokosiewiczi -- (Taczanowski, 1875) ANIMALIA -- CHORDATA -- AVES -- GALLIFORMES -- PHASIANIDAE Common names: Caucasian Grouse; Caucasian Black Grouse European Red List Assessment European Red List Status LC -- Least Concern, (IUCN version 3.1) Assessment Information Year published: 2015 Date assessed: 2015-03-31 Assessor(s): BirdLife International Reviewer(s): Symes, A. Compiler(s): Ashpole, J., Burfield, I., Ieronymidou, C., Pople, R., Wheatley, H. & Wright, L. Assessment Rationale European regional assessment: Least Concern (LC) EU27 regional assessment: Not Applicable (NA) This species has a very large range, and hence does not approach the thresholds for Vulnerable under the range size criterion (Extent of Occurrence 10% in ten years or three generations, or with a specified population structure). The population trend is not known, but the population is not believed to be decreasing sufficiently rapidly to approach the thresholds under the population trend criterion (30% decline over ten years or three generations). For these reasons the species is evaluated as Least Concern in Europe. The bird is not recorded from the EU27 and is assessed as Not Applicable (NA) for this region. Occurrence Countries/Territories of Occurrence Native: Armenia; Azerbaijan; Georgia; Russian Federation; Turkey Population The European population is estimated at 11,500-25,500 calling or lekking males, which equates to 22,900-50,900 mature individuals. The species does not occur in the EU27. For details of national estimates, see Supplementary PDF. Trend In Europe the population size trend is unknown. For details of national estimates, see Supplementary PDF. Habitats and Ecology This species is found in subalpine and alpine meadows, on north-facing slopes with Rhododendron and juniper (Juniperus), and on the edge of birch forest in spring and winter, at elevations of 1,300–3,000 m (Gavashelishvili and Javakhishvili 2010). -

Phasianinae Species Tree

Phasianinae Blood Pheasant,Ithaginis cruentus Ithaginini ?Western Tragopan, Tragopan melanocephalus Satyr Tragopan, Tragopan satyra Blyth’s Tragopan, Tragopan blythii Temminck’s Tragopan, Tragopan temminckii Cabot’s Tragopan, Tragopan caboti Lophophorini ?Snow Partridge, Lerwa lerwa Verreaux’s Monal-Partridge, Tetraophasis obscurus Szechenyi’s Monal-Partridge, Tetraophasis szechenyii Chinese Monal, Lophophorus lhuysii Himalayan Monal, Lophophorus impejanus Sclater’s Monal, Lophophorus sclateri Koklass Pheasant, Pucrasia macrolopha Wild Turkey, Meleagris gallopavo Ocellated Turkey, Meleagris ocellata Tetraonini Ruffed Grouse, Bonasa umbellus Hazel Grouse, Tetrastes bonasia Chinese Grouse, Tetrastes sewerzowi Greater Sage-Grouse / Sage Grouse, Centrocercus urophasianus Gunnison Sage-Grouse / Gunnison Grouse, Centrocercus minimus Dusky Grouse, Dendragapus obscurus Sooty Grouse, Dendragapus fuliginosus Sharp-tailed Grouse, Tympanuchus phasianellus Greater Prairie-Chicken, Tympanuchus cupido Lesser Prairie-Chicken, Tympanuchus pallidicinctus White-tailed Ptarmigan, Lagopus leucura Rock Ptarmigan, Lagopus muta Willow Ptarmigan / Red Grouse, Lagopus lagopus Siberian Grouse, Falcipennis falcipennis Spruce Grouse, Canachites canadensis Western Capercaillie, Tetrao urogallus Black-billed Capercaillie, Tetrao parvirostris Black Grouse, Lyrurus tetrix Caucasian Grouse, Lyrurus mlokosiewiczi Tibetan Partridge, Perdix hodgsoniae Gray Partridge, Perdix perdix Daurian Partridge, Perdix dauurica Reeves’s Pheasant, Syrmaticus reevesii Copper Pheasant, Syrmaticus -

Assessment of Genetic Variation and Evolutionary History of Caucasian Grouse (Lyrurus Mlokosiewiczi)

Ornis Fennica 96: 55–63. 2019 Assessment of genetic variation and evolutionary history of Caucasian Grouse (Lyrurus mlokosiewiczi) Maryam Mostajeran, Mansoureh Malekian*, Sima Fakheran, Marine Murtskhvaladze, Davoud Fadakar & Nader Habibzadeh M. Mostajeran, M. Malekian, S. Fakheran, D. Fadakar, Department of Natural Re- sources, Isfahan University of Technology, Isfahan, Iran. *Corresponding author’s e- mail: [email protected] M. Murtskhvaladze, Institute of Ecology, Ilia State University, Tbilisi, Georgia N. Habibzadeh, Department of Environmental Science, Tabriz Branch, Islamic Azad Uni- versity, Tabriz, Iran Received 8 January 2019, accepted 2 April 2019 Caucasian Grouse (Lyrurus mlokosiewiczi) is an endemic species found in the Caucasus whose population is declining. Initial assessment of genetic variation and phylogenetic status of the species confirmed the monophyly of L. mlokosiewiczias and indicated a sister relationship between L. mlokosiewiczi and L. tetrix (Black grouse). Further the Caucasian grouse from Georgia, Caucasus and Iran created three genetic groups with no shared haplotype. This separation could be the result of different evolutionary events or geo- graphic distances between them. Four different haplotypes were identified in north-west- ern Iran, distributed inside and outside Arasbaran protected area (APA), suggesting the expansion of APA to include Caucasian grouse habitats in the Kalibar Mountains (west- ern APA) and enhance the protection of the species in the region. 1. Introduction most species have only persisted in places de- scribed as refugia (Stewart et al. 2010). With the Levels of genetic diversity in a particular species amelioration of climate, species expanded from are determined by various factors, including its one or several refugia and colonised uninhabited evolutionary history, past climatic events, and cur- areas (Hewitt 2004). -

NL1 (Icke-Tättingar) Ver

Nr Vetenskapligt namn Engelskt namn Svenskt namn (noter) 1 STRUTHIONIFORMES STRUTSFÅGLAR 2 Struthionidae Ostriches Strutsar 3 Struthio camelus Common Ostrich struts 4 Struthio molybdophanes Somali Ostrich somaliastruts 5 6 RHEIFORMES NANDUFÅGLAR 7 Rheidae Rheas Nanduer 8 Rhea americana Greater Rhea större nandu 9 Rhea pennata Lesser Rhea mindre nandu 10 11 APTERYGIFORMES KIVIFÅGLAR 12 Apterygidae Kiwis Kivier 13 Apteryx australis Southern Brown Kiwi sydkivi 14 Apteryx mantelli North Island Brown Kiwi brunkivi 15 Apteryx rowi Okarito Kiwi okaritokivi 16 Apteryx owenii Little Spotted Kiwi mindre fläckkivi 17 Apteryx haastii Great Spotted Kiwi större fläckkivi 18 19 CASUARIIFORMES KASUARFÅGLAR 20 Casuariidae Cassowaries, Emu Kasuarer 21 Casuarius casuarius Southern Cassowary hjälmkasuar 22 Casuarius bennetti Dwarf Cassowary dvärgkasuar 23 Casuarius unappendiculatus Northern Cassowary enflikig kasuar 24 Dromaius novaehollandiae Emu emu 25 26 TINAMIFORMES TINAMOFÅGLAR 27 Tinamidae Tinamous Tinamoer 28 Tinamus tao Grey Tinamou grå tinamo 29 Tinamus solitarius Solitary Tinamou solitärtinamo 30 Tinamus osgoodi Black Tinamou svart tinamo 31 Tinamus major Great Tinamou större tinamo 32 Tinamus guttatus White-throated Tinamou vitstrupig tinamo 33 Nothocercus bonapartei Highland Tinamou höglandstinamo 34 Nothocercus julius Tawny-breasted Tinamou brunbröstad tinamo 35 Nothocercus nigrocapillus Hooded Tinamou kamtinamo 36 Crypturellus berlepschi Berlepsch's Tinamou sottinamo 37 Crypturellus cinereus Cinereous Tinamou askgrå tinamo 38 Crypturellus soui -

Necklace-Style Radio-Transmitters Are Associated with Changes in Display Vocalizations of Male Greater Sage-Grouse Author(S): Marcella R

Necklace-style radio-transmitters are associated with changes in display vocalizations of male greater sage-grouse Author(s): Marcella R. Fremgen, Daniel Gibson, Rebecca L. Ehrlich, Alan H. Krakauer, Jennifer S. Forbey, Erik J. Blomberg, James S. Sedinger and Gail L. Patricelli Source: Wildlife Biology, () Published By: Nordic Board for Wildlife Research https://doi.org/10.2981/wlb.00236 URL: http://www.bioone.org/doi/full/10.2981/wlb.00236 BioOne (www.bioone.org) is a nonprofit, online aggregation of core research in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences. BioOne provides a sustainable online platform for over 170 journals and books published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Web site, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/page/terms_of_use. Usage of BioOne content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non-commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. Wildlife Biology 2017: wlb.00236 doi: 10.2981/wlb.00236 © 2016 The Authors. This is an Open Access article Subject Editor: Olafur Nielsen. Editor-in-Chief: Ilse Storch. Accepted 19 July 2016 Necklace-style radio-transmitters are associated with changes in display vocalizations of male greater sage-grouse Marcella R. Fremgen, Daniel Gibson, Rebecca L. Ehrlich, Alan H. -

Supplementary Material

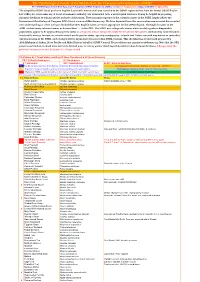

Lyrurus mlokosiewiczi (Caucasian Grouse) European Red List of Birds Supplementary Material The European Union (EU27) Red List assessments were based principally on the official data reported by EU Member States to the European Commission under Article 12 of the Birds Directive in 2013-14. For the European Red List assessments, similar data were sourced from BirdLife Partners and other collaborating experts in other European countries and territories. For more information, see BirdLife International (2015). Contents Reported national population sizes and trends p. 2 Trend maps of reported national population data p. 3 Sources of reported national population data p. 5 Species factsheet bibliography p. 6 Recommended citation BirdLife International (2015) European Red List of Birds. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities. Further information http://www.birdlife.org/datazone/info/euroredlist http://www.birdlife.org/europe-and-central-asia/european-red-list-birds-0 http://www.iucnredlist.org/initiatives/europe http://ec.europa.eu/environment/nature/conservation/species/redlist/ Data requests and feedback To request access to these data in electronic format, provide new information, correct any errors or provide feedback, please email [email protected]. THE IUCN RED LIST OF THREATENED SPECIES™ BirdLife International (2015) European Red List of Birds Lyrurus mlokosiewiczi (Caucasian Grouse) Table 1. Reported national breeding population size and trends in Europe1. Country (or Population estimate Short-term -

The Historical Biogeography of Terrestrial Gamebirds (Aves: Galliformes)

The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgementTown of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Cape Published by the University ofof Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University 1 The historical biogeography of terrestrial gamebirds (Aves: Galliformes) Vincent Charl van der Merwe Supervisor: Professor Tim CroweTown Cape of DST/NRF Centre of Excellence at the Percy FitzPatrick Institute of African Ornithology University of Cape Town Rondebosch, 7701, South Africa e-mail: [email protected] University February 2011 Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Conservation Biology 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................. 3 Abstract ……………………………………………………………………………………………….. 4 Chapter 1: Inferring the biogeographical history of terrestrial gamebirds (Aves: Galliformes) using a novel approach: The direct analysis of vicariance Gamebirds and their systematics ......................…..…………..……………………………..……. 5 Centre of origin: North or South? ……………………………………………………………...…….. 7 A short history of biogeographical analysis ………………………………………………..……….. 9 Problems with the cladistic approach ……………………………………………………………… 10 Vicariance biogeography ……………………………………………………………………………. 12 Town Chapter 2: Poultry