Heraldry in Jamaica 1660 to 2010. by Duncan Sutherland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

After the Treaties: a Social, Economic and Demographic History of Maroon Society in Jamaica, 1739-1842

University of Southampton Research Repository Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis and, where applicable, any accompanying data are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non‐commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis and the accompanying data cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content of the thesis and accompanying research data (where applicable) must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder/s. When referring to this thesis and any accompanying data, full bibliographic details must be given, e.g. Thesis: Author (Year of Submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University Faculty or School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. University of Southampton Department of History After the Treaties: A Social, Economic and Demographic History of Maroon Society in Jamaica, 1739-1842 Michael Sivapragasam A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History June 2018 i ii UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON ABSTRACT DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY Doctor of Philosophy After the Treaties: A Social, Economic and Demographic History of Maroon Society in Jamaica, 1739-1842 Michael Sivapragasam This study is built on an investigation of a large number of archival sources, but in particular the Journals and Votes of the House of the Assembly of Jamaica, drawn from resources in Britain and Jamaica. Using data drawn from these primary sources, I assess how the Maroons of Jamaica forged an identity for themselves in the century under slavery following the peace treaties of 1739 and 1740. -

British Isles

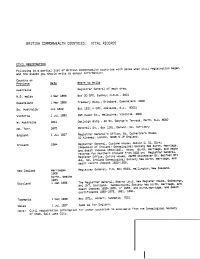

BRITISH COMMONWEALTH COUNTRIES: VITAL RECORDS CIVIL REGISTRATICN Following is a partial list of British Ccmmcnwealth countries with dates when civil registration began, and the places you should writ~ to obtain information: Ccuntry or Prevince Q!!! Where to Write .Au$t'ralia Registrar Ganer-a! of each area. N.S. wales 1 Mar 1856 Sex 30 GPO, Sydney, N.S.W., 2001 Queensland 1 Mar 1856 Treasury Bldg., Brisbane, Queensland 4000 So. Australia Jul 1842 8ex 1531 H Gr\), Adelaide, S.A. 5CCCl Victoria 1 Jul 1853 295 Cuesn St., Melbourne, Victoria XCO W. .Australia 1841 Cak!eigh 61dg., 22 St. Gear-ge's Terrace, Perth, W.A. eoco Nc. Terr. 1870 Mitchell St., Box 1281. OarNin, Nc. Territory England 1 Jul 1837 Registrar General's Office, St. catherine's House, 10 Kinsway. Loncen, 'AC2S 6 JP England. Ireland 1864 Registrar General, Custcme House. Dublin C. 10, Eire, (Recuolic(Republic of Ireland) Genealogical Society has bir~h, marriage, and death indexes 1864-1921. Nete: Birth, rtarl"'iage,rmt'l"'iage, atld death records farfor Nor~hern Ireland frcm 1922 an: Registrar General, Regis~erOffice, Oxford House. 49~5 Chichester St. Selfast STI 4HL, No~ !re1.a.rld Genealcgical Scciety has birth, narriage, and death recordreccrd indexes 1922-l959~ New Z!!aland marriages Registrar General, P.O~ Sox =023, wellingtcn, New Zealand. 1008 birth, deaths 1924 Scotland 1 Jan 1855 The Registrar General, Search Unit, New Register House, Edinburgh, EHl 3YT, SCCtland~ Genealogical Saei~tyScei~ty has bir~h,birth, marriage, and death indexes 1855-1955, or 1956, and birt%'\ crarriage, and death cer~ificates 1855-1875, 1881. -

Solanaceae) Flower–Visitor Network in an Atlantic Forest Fragment in Southern Brazil

diversity Article Bee Diversity and Solanum didymum (Solanaceae) Flower–Visitor Network in an Atlantic Forest Fragment in Southern Brazil Francieli Lando 1 ID , Priscila R. Lustosa 1, Cyntia F. P. da Luz 2 ID and Maria Luisa T. Buschini 1,* 1 Programa de Pós Graduação em Biologia Evolutiva da Universidade Estadual do Centro-Oeste, Rua Simeão Camargo Varela de Sá 03, Vila Carli, Guarapuava 85040-080, Brazil; [email protected] (F.L.); [email protected] (P.R.L.) 2 Research Centre of Vascular Plants, Palinology Research Centre, Botanical Institute of Sao Paulo Government, Av. Miguel Stéfano, 3687 Água Funda, São Paulo 04045-972, Brazil; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 9 November 2017; Accepted: 8 January 2018; Published: 11 January 2018 Abstract: Brazil’s Atlantic Forest biome is currently undergoing forest loss due to repeated episodes of devastation. In this biome, bees perform the most frequent pollination system. Over the last decade, network analysis has been extensively applied to the study of plant–pollinator interactions, as it provides a consistent view of the structure of plant–pollinator interactions. The aim of this study was to use palynological studies to obtain an understanding of the relationship between floral visitor bees and the pioneer plant S. didymum in a fragment of the Atlantic Forest, and also learn about the other plants that interact to form this network. Five hundred bees were collected from 32 species distributed into five families: Andrenidae, Apidae, Colletidae, Megachilidae, and Halictidae. The interaction network consisted of 21 bee species and 35 pollen types. -

Jupiter and the Bee

Jupiter and the Bee At the beginning of time, the honeybee had no stinger. This left the bee with no way to protect her honey. The bee worked very hard to make her honey. But people were always taking it from her. This made the bee mad. The bee needed help. She needed a way to protect her honey. The bee decided to ask the gods for help. She took some of her best honey. Then she flew to Mount Olympus. That is where the gods lived. The bee went to see Jupiter. Jupiter was king of the gods. She brought him the honey as a gift. © 2018 Reading Is Fundamental • Content and art created by Simone Ribke Jupiter and the Bee Jupiter loved the honey. He had never tasted something so sweet. Jupiter said it was a great gift. In return, Jupiter promised to give the bee a gift. He asked her what she wanted. The bee asked Jupiter to give her a stinger. She would use it to keep people away from her honey. She would sting people who tried to take honey from her. Jupiter did not like this idea because he loved people. He did not want them to get stung. But he had made her a promise. Jupiter gave the bee a stinger, but using it came at a price. If she uses her stinger, she will die. The bee would have to choose. Will she protect her honey and die? Or will she let people take her honey and live? Jupiter gave stingers to all bees. -

WHAT IS a FARM? AGRICULTURE, DISCOURSE, and PRODUCING LANDSCAPES in ST ELIZABETH, JAMAICA by Gary R. Schnakenberg a DISSERTATION

WHAT IS A FARM? AGRICULTURE, DISCOURSE, AND PRODUCING LANDSCAPES IN ST ELIZABETH, JAMAICA By Gary R. Schnakenberg A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Geography – Doctor of Philosophy 2013 ABSTRACT WHAT IS A FARM? AGRICULTURE, DISCOURSE, AND PRODUCING LANDSCAPES IN ST. ELIZABETH, JAMAICA By Gary R. Schnakenberg This dissertation research examined the operation of discourses associated with contemporary globalization in producing the agricultural landscape of an area of rural Jamaica. Subject to European colonial domination from the time of Columbus until the 1960s and then as a small island state in an unevenly globalizing world, Jamaica has long been subject to operations of unequal power relationships. Its history as a sugar colony based upon chattel slavery shaped aspects of the society that emerged, and left imprints on the ethnic makeup of the population, orientation of its economy, and beliefs, values, and attitudes of Jamaican people. Many of these are smallholder agriculturalists, a livelihood strategy common in former colonial places. Often ideas, notions, and practices about how farms and farming ‘ought-to-be’ in such places results from the operations and workings of discourse. As advanced by Foucault, ‘discourse’ refers to meanings and knowledge circulated among people and results in practices that in turn produce and re-produce those meanings and knowledge. Discourses define what is right, correct, can be known, and produce ‘the world as it is.’ They also have material effects, in that what it means ‘to farm’ results in a landscape that emerges from those meanings. In Jamaica, meanings of ‘farms’ and ‘farming’ have been shaped by discursive elements of contemporary globalization such as modernity, competition, and individualism. -

Heraldic Terms

HERALDIC TERMS The following terms, and their definitions, are used in heraldry. Some terms and practices were used in period real-world heraldry only. Some terms and practices are used in modern real-world heraldry only. Other terms and practices are used in SCA heraldry only. Most are used in both real-world and SCA heraldry. All are presented here as an aid to heraldic research and education. A LA CUISSE, A LA QUISE - at the thigh ABAISED, ABAISSÉ, ABASED - a charge or element depicted lower than its normal position ABATEMENTS - marks of disgrace placed on the shield of an offender of the law. There are extreme few records of such being employed, and then only noted in rolls. (As who would display their device if it had an abatement on it?) ABISME - a minor charge in the center of the shield drawn smaller than usual ABOUTÉ - end to end ABOVE - an ambiguous term which should be avoided in blazon. Generally, two charges one of which is above the other on the field can be blazoned better as "in pale an X and a Y" or "an A and in chief a B". See atop, ensigned. ABYSS - a minor charge in the center of the shield drawn smaller than usual ACCOLLÉ - (1) two shields side-by-side, sometimes united by their bottom tips overlapping or being connected to each other by their sides; (2) an animal with a crown, collar or other item around its neck; (3) keys, weapons or other implements placed saltirewise behind the shield in a heraldic display. -

The Colours of the Fleet

THE COLOURS OF THE FLEET TCOF BRITISH & BRITISH DERIVED ENSIGNS ~ THE MOST COMPREHENSIVE WORLDWIDE LIST OF ALL FLAGS AND ENSIGNS, PAST AND PRESENT, WHICH BEAR THE UNION FLAG IN THE CANTON “Build up the highway clear it of stones lift up an ensign over the peoples” Isaiah 62 vv 10 Created and compiled by Malcolm Farrow OBE President of the Flag Institute Edited and updated by David Prothero 15 January 2015 © 1 CONTENTS Chapter 1 Page 3 Introduction Page 5 Definition of an Ensign Page 6 The Development of Modern Ensigns Page 10 Union Flags, Flagstaffs and Crowns Page 13 A Brief Summary Page 13 Reference Sources Page 14 Chronology Page 17 Numerical Summary of Ensigns Chapter 2 British Ensigns and Related Flags in Current Use Page 18 White Ensigns Page 25 Blue Ensigns Page 37 Red Ensigns Page 42 Sky Blue Ensigns Page 43 Ensigns of Other Colours Page 45 Old Flags in Current Use Chapter 3 Special Ensigns of Yacht Clubs and Sailing Associations Page 48 Introduction Page 50 Current Page 62 Obsolete Chapter 4 Obsolete Ensigns and Related Flags Page 68 British Isles Page 81 Commonwealth and Empire Page 112 Unidentified Flags Page 112 Hypothetical Flags Chapter 5 Exclusions. Page 114 Flags similar to Ensigns and Unofficial Ensigns Chapter 6 Proclamations Page 121 A Proclamation Amending Proclamation dated 1st January 1801 declaring what Ensign or Colours shall be borne at sea by Merchant Ships. Page 122 Proclamation dated January 1, 1801 declaring what ensign or colours shall be borne at sea by merchant ships. 2 CHAPTER 1 Introduction The Colours of The Fleet 2013 attempts to fill a gap in the constitutional and historic records of the United Kingdom and the Commonwealth by seeking to list all British and British derived ensigns which have ever existed. -

Ghana Fax 513-977-4150 [email protected]

Bi-Okoto Drum & Dance Theatre Akwaaba— EDUCATION/COMMUNITY RELATIONS 650 WALNUT ST. CINCINNATI, OH 45202 PHONE 513-977-4116 Welcome to Ghana FAX 513-977-4150 WWW.CINCINNATIARTS.ORG [email protected] Classroom photo by Rich Sofranko STUDY GUIDE Written by Bi-Okoto Drum & Dance Theatre Edited & Designed by Kathleen Riemenschneider Artists on Tour GHANA Ghana is the first African country south of the Sahara to achieve independence led by Osagyefo Dr. Kwame Nkrumah in 1957. The colonial power was Britain. However, the British were not the first Europeans to arrive in Ghana. The Portuguese were the first to arrive and they named the place the Gold Coast. This was the name of the country until independence when it was changed to Ghana. The British moved the capital of Ghana from Cape Coast to Accra in 1876. The oldest traces of sedentary habitation in Ghana date back 30,000 or 40,000 years along the coast, notably near Tema, although little is known about the human beings who lived there. Ghana has a population of about 17.7 million and has 10 regions: the Northern, Upper West, Upper East, Volta, Ashanti, Western, Eastern, Central, Brong - Ahafo and Greater Accra. Ghana is well known for its friendly people and its well-acclaimed hospitality. GEOGRAPHY, LAND & CLIMATE Ghana is located on West Africa’s Gulf of Guinea only a few degrees north of the Equator. It is in Western Africa, bordering the North Atlantic Ocean between Cote D’Ivoire (known as the Ivory Coast) and Togo. Half of the country lies less than 500 ft. -

The Order of Military Merit to Corporal R

Chapter Three The Order Comes to Life: Appointments, Refinements and Change His Excellency has asked me to write to inform you that, with the approval of The Queen, Sovereign of the Order, he has appointed you a Member. Esmond Butler, Secretary General of the Order of Military Merit to Corporal R. L. Mailloux, I 3 December 1972 nlike the Order of Canada, which underwent a significant structural change five years after being established, the changes made to the Order of Military U Merit since 1972 have been largely administrative. Following the Order of Canada structure and general ethos has served the Order of Military Merit well. Other developments, such as the change in insignia worn on undress ribbons, the adoption of a motto for the Order and the creation of the Order of Military Merit paperweight, are examined in Chapter Four. With the ink on the Letters Patent and Constitution of the Order dry, The Queen and Prime Minister having signed in the appropriate places, and the Great Seal affixed thereunto, the Order had come into being, but not to life. In the beginning, the Order consisted of the Sovereign and two members: the Governor General as Chancellor and a Commander of the Order, and the Chief of the Defence Staff as Principal Commander and a similarly newly minted Commander of the Order. The first act of Governor General Roland Michener as Chancellor of the Order was to appoint his Secretary, Esmond Butler, to serve "as a member of the Advisory Committee of the Order." 127 Butler would continue to play a significant role in the early development of the Order, along with future Chief of the Defence Staff General Jacques A. -

Arms and the (Tax-)Man: the Use and Taxation of Armorial Bearings in Britain, 1798–1944

Arms and the (tax-)man: The use and taxation of armorial bearings in Britain, 1798–1944. Philip Daniel Allfrey BA, BSc, MSc(Hons), DPhil. Dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MLitt in Family and Local History at the University of Dundee. October 2016 Abstract From 1798 to 1944 the display of coats of arms in Great Britain was taxed. Since there were major changes to the role of heraldry in society in the same period, it is surprising that the records of the tax have gone unstudied. This dissertation evaluates whether the records of the tax can say something useful about heraldry in this period. The surviving records include information about individual taxpayers, statistics at national and local levels, and administrative papers. To properly interpret these records, it was necessary to develop a detailed understanding of the workings of the tax; the last history of the tax was published in 1885 and did not discuss in detail how the tax was collected. A preliminary analysis of the records of the armorial bearings tax leads to five conclusions: the financial or social elite were more likely to pay the tax; the people who paid the tax were concentrated in fashionable areas; there were differences between the types of people who paid the tax in rural and urban areas; women and clergy were present in greater numbers than one might expect; and the number of taxpayers grew rapidly in the middle of the nineteenth century, but dropped off after 1914. However, several questions have to be answered before -

Heraldry & the Parts of a Coat of Arms

Heraldry reference materials The tomb of Geoffrey V, Count of Anjou (died 1151) is the first recorded example of hereditary armory in Europe. The same shield shown here is found on the tomb effigy of his grandson, William Longespée, 3rd Earl of Salisbury. Heraldry & the Parts of a Coat of Arms From fleur-de-lis.com Here are some charts from Irish surnames.com, but you can look up more specific information for you by searching “charges” and the words that allude to your ancestors’ backgrounds and cultures, if you prefer. Also try: http://www.rarebooks.nd.edu/digital/heraldry/charges/crowns.html for a good reference source on charges. THE COLORS ON COATS OF ARMS Color Meaning Image Generosity Or (Gold) Argent (Silver or White) Sincerity, Peace Justice, Sovereignty, Purpure (Purple) Regal Warrior, Martyr, Military Gules (Red) Strength Azure (Blue) Strength, Loyalty Vert (Green) Hope, loyalty in love Sable (Black) Constancy, Grief Tenne or Tawny (Orange) Worthwhile Ambition Sanguine or Murray Victorious, Patient in Battle (Maroon) LINES ON COATS OF ARMS Name Meaning Image Irish Example Clouds or Air Nebuly Line Wavy Line Sea or Water Gillespie Embattled Fire, Town-Wall Patterson Line Engrailed Earth, Land Feeney Line Invecked Earth, Land Rowe Line Indented Fire Power Line HERALDIC BEASTS Name Meaning Image Irish Example Fierce Courage. In Ireland the Lion represented the 'lion' season, Lawlor Lion prior to the full arrival of Dillon Summer. The symbol can Condon also represent a great Warrior or Chief. Tiger Fierceness and valour Of Regal origin, one of high nature. In Ireland the Fish is associated with the legend of Fionn who became the first to Roche Fish taste the 'salmon of knowledge'. -

The BC Coat of Arms & the Man Who Made Them

1983 2013 The Patron of the BC/Yukon Branch: The Honourable Judith Guichon, OBC, Lieutenant Governor of British Columbia Winter 2012 Vol. 7 No. 2 Issue 14 The BC Coat of Arms & the Man Who Made Them Our First Heraldist - Canon Arthur John Beanlands 1857-1917 by Carl A. Larsen Arms, including the Royal Crest of the crowned lion standing on the imperial crown, was widely used on official documents. This was general practice throughout the Empire. However, in this province, Canon Beanlands, Rector of Christ Church Cathedral in from the 1870s the Royal Crest flanked by the initials “B.C.” began Victoria for twenty-five years, (1884-1909) has the undisputed to be used as a type of provincial insignia. (See Fig. 1) distinction of being the first recognized heraldist in the province In the early 1890s the need to review the Great Seal of the and the first resident to receive a grant of arms. However, Province seems to have provided an opportunity for the Beanlands’ lasting legacy to the province, is undoubtedly his Province’s first heraldic enthusiast, Canon Arthur Beanlands of design for the British Columbia coat of arms. Sir Conrad Swan, Victoria, to encourage the government of the day to adopt a more York Herald at the time and later Garter King of Arms, has high praise for Beanlands and his design. “The author of this heraldic design was Arthur John Beanlands, Rector and Canon Residentiary of Christchurch Fig. 1 Device displaying Cathedral, Victoria. He was an armorial enthusiast and appears to the royal crest with letters have been the first resident of the province to receive a grant of BC added to distinguish it arms.