Infection to Sentinel Mice by Contaminated Bedding

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

C O N F E R E N C E 22 27 April 2016

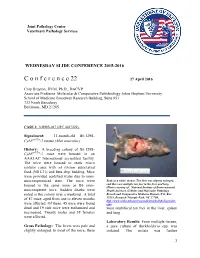

Joint Pathology Center Veterinary Pathology Services WEDNESDAY SLIDE CONFERENCE 2015-2016 C o n f e r e n c e 22 27 April 2016 Cory Brayton, DVM, Ph.D., DACVP Associate Professor, Molecular & Comparative Pathobiology Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Broadway Research Building, Suite 851 733 North Broadway Baltimore, MD 21205 CASE I: NIEHS-087 (JPC 4017222). Signalment: 11-month-old B6.129S- Cybbtm1Din/J mouse (Mus musculus) History: A breeding colony of B6.129S- Cybbtm1Din/J mice were housed in an AAALAC International accredited facility. The mice were housed in static micro isolator cases with ad libitum autoclaved food (NIH-31) and beta chip bedding. Mice were provided acidified water due to imm- unocompromised state. The mice were Body as a while, mouse. The liver was slightly enlarged, housed in the same room as B6 imm- and there are multiple tan foci in the liver and lung. (Photo courtesy of: National Institute of Environmental unocompetent mice. Sudden deaths were Health Sciences, Cellular and Molecular Pathology noted in the colony over a weekend. A total Branch and Comparative Medicine Branch, P.O. Box of 87 mice, aged from one to eleven months 12233, Research Triangle Park, NC 27709, http://www.niehs.nih.gov/research/atniehs/labs/lep/index. were affected. Of these, 45 mice were found cfm) dead and 19 sick mice were euthanized and were multifocal tan foci in the liver, spleen necropsied. Twenty males and 38 females and lung. were affected. Laboratory Results: From multiple tissues, Gross Pathology: The livers were pale and a pure culture of Burkholderia spp. -

Helicobacter Hepaticus Model of Infection: the Human Hepatocellular Carcinoma Controversy

Review articles Helicobacter hepaticus model of infection: the human hepatocellular carcinoma controversy Yessica Agudelo Zapata, MD,1 Rodrigo Castaño Llano, MD,2 Mauricio Corredor, PhD.3 1 Medical Doctor and General Surgeon in the Abstract Gastrohepatology Group at Universidad de Antioquia in Medellin, Colombia The discovery of Helicobacter 30 years ago by Marshall and Warren completely changed thought about peptic 2 Gastrointestinal Surgeon and Endoscopist in the and duodenal ulcers. The previous paradigm posited the impossibility of the survival of microorganisms in the Gastrohepatology Group at the Universidad de stomach’s low pH environment and that, if any microorganisms survived, they would stay in the duodenum Antioquia in Medellin, Colombia 3 Institute Professor of Biology in the Faculty of or elsewhere in the intestine. Today the role of H. pylori in carcinogenesis is indisputable, but little is known Natural Sciences and the GEBIOMIC Group the about other emerging species of the genus Helicobacter in humans. Helicobacter hepaticus is one of these Gastroenterology Group at the Universidad de species that has been studied most, after H. pylori. We now know about their microbiological, genetic and Antioquia in Medellin, Colombia pathogenic relationships with HCC in murine and human infections. This review aims to show the medical and ......................................... scientifi c community the existence of new species of Helicobacter that have pathogenic potential in humans, Received: 07-05-13 thus encouraging research. Accepted: 27-08-13 Keywords Helicobacter hepaticus, Helicobacter pylori, Helicobacter spp., hepatocellular carcinoma. INTRODUCTION bacterium can infect animals including mice, dogs and ger- bils which could lead to a proposal to use H. -

Rapid Identification of Klebsiella Pneumoniae, Corynebacterium Kutscheri, and Streptococcus Pneumoniae Using Triplex Polymerase Chain Reaction in Rodents

Exp. Anim. 62(1), 35–40, 2013 —Original— Rapid Identification of Klebsiella pneumoniae, Corynebacterium kutscheri, and Streptococcus pneumoniae Using Triplex Polymerase Chain Reaction in Rodents Eui-Suk JEONG1), Kyoung-Sun Lee1,2), Seung-Ho HEO1,3), Jin-Hee SEO1), and Yang-Kyu CHOI1) 1)Department of Laboratory Animal Medicine, College of Veterinary Medicine, Konkuk University, 1 Hwayang-dong, Gwangjin-gu, Seoul 143-701, Republic of Korea 2)Osong Medical Innovation Foundation Laboratory Animal Center, 186 Osong Saengmyung-Ro, Gangoe-myeon, Cheongwon-gun, Chungbuk 363-951, Republic of Korea 3)Asan Institute for Life Sciences, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, 388–1 Pungnap-2-dong, Songpa-gu Seoul 138-736, Republic of Korea Abstract: Klebsiella pneumoniae, Corynebacterium kutscheri, and Streptococcus pneumoniae are important pathogens that cause respiratory infections in laboratory rodents. In this study, we used species-specific triplex PCR analysis to directly detect three common bacterial pathogens associated with respiratory diseases. Specific targets were amplified with conventional PCR using thetyrB gene from K. pneumoniae, gyrB gene from C. kutscheri, and ply gene from S. pneumoniae. Our primers were tested against purified DNA from another eleven murine bacteria to determine primer specificity. Under optimal PCR conditions, the triplex assay simultaneously yielded a 931 bp product from K. pneumoniae, a 540 bp product from C. kutscheri, and a 354 bp product from S. pneumoniae. The triplex assay detection thresholds for pure cultures were 10 pg for K. pneumoniae and S. pneumoniae, and 100 pg for C. kutscheri. All three bacteria were successfully identified in the trachea and lung of experimentally infected mice at the same time. -

Endogenous Enterobacteriaceae Underlie Variation in Susceptibility to Salmonella Infection

ARTICLES https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-019-0407-8 Endogenous Enterobacteriaceae underlie variation in susceptibility to Salmonella infection Eric M. Velazquez1, Henry Nguyen1, Keaton T. Heasley1, Cheng H. Saechao1, Lindsey M. Gil1, Andrew W. L. Rogers1, Brittany M. Miller1, Matthew R. Rolston1, Christopher A. Lopez1,2, Yael Litvak 1, Megan J. Liou1, Franziska Faber 1,3, Denise N. Bronner1, Connor R. Tiffany1, Mariana X. Byndloss1,2, Austin J. Byndloss1 and Andreas J. Bäumler 1* Lack of reproducibility is a prominent problem in biomedical research. An important source of variation in animal experiments is the microbiome, but little is known about specific changes in the microbiota composition that cause phenotypic differences. Here, we show that genetically similar laboratory mice obtained from four different commercial vendors exhibited marked phenotypic variation in their susceptibility to Salmonella infection. Faecal microbiota transplant into germ-free mice repli- cated donor susceptibility, revealing that variability was due to changes in the gut microbiota composition. Co-housing of mice only partially transferred protection against Salmonella infection, suggesting that minority species within the gut microbiota might confer this trait. Consistent with this idea, we identified endogenous Enterobacteriaceae, a low-abundance taxon, as a keystone species responsible for variation in the susceptibility to Salmonella infection. Protection conferred by endogenous Enterobacteriaceae could be modelled by inoculating mice with probiotic Escherichia coli, which conferred resistance by using its aerobic metabolism to compete with Salmonella for resources. We conclude that a mechanistic understanding of phenotypic variation can accelerate development of strategies for enhancing the reproducibility of animal experiments. recent survey suggests that the majority of researchers Results have tried and failed to reproduce their own experiments To determine whether genetically similar strains of mice obtained A or experiments from other scientists1. -

Alvinella Pompejana Is an Endemic Inhabitant Tof Deep-Sea Hydrothermal Vents Located from 21°N to 32°S Latitude on the East Pacific Rise (1)

Metagenome analysis of an extreme microbial symbiosis reveals eurythermal adaptation and metabolic flexibility Joseph J. Grzymskia,1, Alison E. Murraya,1, Barbara J. Campbellb, Mihailo Kaplarevicc, Guang R. Gaoc,d, Charles Leee, Roy Daniele, Amir Ghadirif, Robert A. Feldmanf, and Stephen C. Caryb,d,2 aDivision of Earth and Ecosystem Sciences, Desert Research Institute, 2215 Raggio Parkway, Reno, NV 89512; bCollege of Marine and Earth Studies, University of Delaware, Lewes, DE 19958; cDelaware Biotechnology Institute, 15 Innovation Way, Newark, DE 19702; dElectrical and Computer Engineering, University of Delaware, 140 Evans Hall, Newark, DE 19716; eDepartment of Biological Sciences, University of Waikato, Hamilton, New Zealand; fSymBio Corporation, 1455 Adams Drive, Menlo Park, CA 94025 Edited by George N. Somero, Stanford University, Pacific Grove, CA, and approved September 17, 2008 (received for review March 20, 2008) Hydrothermal vent ecosystems support diverse life forms, many of the thermal tolerance of a structural protein biomarker (5) which rely on symbiotic associations to perform functions integral supports the assertion that A. pompejana is likely among the to survival in these extreme physicochemical environments. Epsi- most thermotolerant and eurythermal metazoans on Earth lonproteobacteria, found free-living and in intimate associations (6, 7). with vent invertebrates, are the predominant vent-associated A. pompejana is characterized by a filamentous microflora that microorganisms. The vent-associated polychaete worm, Alvinella forms cohesive hair-like projections from mucous glands lining pompejana, is host to a visibly dense fleece of episymbionts on its the polychaete’s dorsal intersegmentary spaces (8). The episym- dorsal surface. The episymbionts are a multispecies consortium of biont community is constrained to the bacterial subdivision, Epsilonproteobacteria present as a biofilm. -

Bacterial Α -Macroglobulins: Colonization Factors Acquired By

Open Access Research2004BuddetVolume al. 5, Issue 6, Article R38 Bacterial α2-macroglobulins: colonization factors acquired by comment horizontal gene transfer from the metazoan genome? Aidan Budd*, Stephanie Blandin*, Elena A Levashina† and Toby J Gibson* Addresses: *European Molecular Biology Laboratory, 69012 Heidelberg, Germany. †UPR 9022 du CNRS, IBMC, rue René Descartes, F-67087 Strasbourg CEDEX, France. Correspondence: Toby J Gibson. E-mail: [email protected] reviews Published: 26 May 2004 Received: 20 February 2004 Revised: 2 April 2004 Genome Biology 2004, 5:R38 Accepted: 8 April 2004 The electronic version of this article is the complete one and can be found online at http://genomebiology.com/2004/5/6/R38 © 2004 Budd et al.; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article: verbatim copying and redistribution of this article are permitted in all media for any purpose, provided this notice is preserved along with the article's original URL. reports Bacterial<p>Invasivebacteriawhichprovidesp> exploit by aα major2 horizontal-macroglobulins: bacteria different metazoan are gene host known defensetransfer.tissues, colonization to have againstshare Closely captured almostfactors invasive related none andacquired speciesbacteria, adapted of their by such trapping hoeukarycolonization rizontalas <it>Helicobacterotic attacking genehost genes. genes.transfer proteases The They pylori proteasefrom alsorequired </it>andthe readily inhibitormetazoan by <it>Helicobacteracquire parasites α genome?<sub>2</sub>-macroglobulin colonizing for successful hepatic genes invasion.</ fus</it>,rom other Abstract Background: Invasive bacteria are known to have captured and adapted eukaryotic host genes. deposited research They also readily acquire colonizing genes from other bacteria by horizontal gene transfer. Closely related species such as Helicobacter pylori and Helicobacter hepaticus, which exploit different host tissues, share almost none of their colonization genes. -

WO 2012/055408 Al

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date . 3 May 2012 (03.05.2012) WO 2012/055408 Al (51) International Patent Classification: DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, CI2Q 1/68 (2006.01) HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IS, JP, KE, KG, KM, KN, KP, KR, KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LT, LU, LY, MA, MD, (21) International Application Number: ME, MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, PCT/DK20 11/000120 NO, NZ, OM, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, QA, RO, RS, RU, (22) International Filing Date: RW, SC, SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, 27 October 201 1 (27.10.201 1) TM, TN, TR, TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, ZW. (25) Filing Language: English (84) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every (26) Publication Language: English kind of regional protection available): ARIPO (BW, GH, (30) Priority Data: GM, KE, LR, LS, MW, MZ, NA, RW, SD, SL, SZ, TZ, 61/407,122 27 October 2010 (27.10.2010) US UG, ZM, ZW), Eurasian (AM, AZ, BY, KG, KZ, MD, PA 2010 70455 27 October 2010 (27.10.2010) DK RU, TJ, TM), European (AL, AT, BE, BG, CH, CY, CZ, DE, DK, EE, ES, FI, FR, GB, GR, HR, HU, IE, IS, IT, (71) Applicant (for all designated States except US): QUAN- LT, LU, LV, MC, MK, MT, NL, NO, PL, PT, RO, RS, TIBACT A/S [DK/DK]; Kettegards Alle 30, DK-2650 SE, SI, SK, SM, TR), OAPI (BF, BJ, CF, CG, CI, CM, Hvidovre (DK). -

Helicobacter Hepaticus Infection Promotes Hepatitis and Preneoplastic Foci in Farnesoid X Receptor (FXR) Deficient Mice

Helicobacter hepaticus Infection Promotes Hepatitis and Preneoplastic Foci in Farnesoid X Receptor (FXR) Deficient Mice The MIT Faculty has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters. Citation Swennes, Alton G., Alexander Sheh, Nicola M. A. Parry, Sureshkumar Muthupalani, Kvin Lertpiriyapong, Alexis Garcia, and James G. Fox. “Helicobacter Hepaticus Infection Promotes Hepatitis and Preneoplastic Foci in Farnesoid X Receptor (FXR) Deficient Mice.” Edited by Makoto Makishima. PLoS ONE 9, no. 9 (September 3, 2014): e106764. As Published http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0106764 Publisher Public Library of Science Version Final published version Citable link http://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/90998 Terms of Use Creative Commons Attribution Detailed Terms http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Helicobacter hepaticus Infection Promotes Hepatitis and Preneoplastic Foci in Farnesoid X Receptor (FXR) Deficient Mice Alton G. Swennes"¤a, Alexander Sheh", Nicola M. A. Parry, Sureshkumar Muthupalani, Kvin Lertpiriyapong¤b, Alexis Garcı´a, James G. Fox* Division of Comparative Medicine, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States of America Abstract Farnesoid X receptor (FXR) is a nuclear receptor that regulates bile acid metabolism and transport. Mice lacking expression of FXR (FXR KO) have a high incidence of foci of cellular alterations (FCA) and liver tumors. Here, we report that Helicobacter hepaticus infection is necessary for the development of increased hepatitis scores and FCA in previously Helicobacter-free FXR KO mice. FXR KO and wild-type (WT) mice were sham-treated or orally inoculated with H. hepaticus. At 12 months post- infection, mice were euthanized and liver pathology, gene expression, and the cecal microbiome were analyzed. -

Tick-Borne Bacterial, Rickettsial, Spirochetal, and Protozoal Diseases

Chapter 22 Tick-Borne Bacterial, Rickettsial, Spirochetal, and Protozoal Diseases Approximately 900 tick species exist worldwide, parasitiz- have increased steadily over the past decade or so (http:// ing a broad array of mammals, including humans, and www3.niaid.nih.gov/research/topics/lyme/introduction/htm). thereby playing a significant role in the transmission of infec- Although Lyme disease and Rocky Mountain spotted fever tious diseases (1). In the United States, tick-borne diseases are well known to the general public, recently emerging are generally seasonal and geographically distributed. They infections, such as ehrlichiosis and anaplasmosis (formerly occur mostly during the spring and summer but can occur known as human granulocytic ehrlichiosis), have now also throughout the year. been firmly established in the country. The increasing reports These blood-feeding arthropods that parasitize all verte- of tick-borne diseases likely reflect improved awareness, brates can be classified into three families: (i) Ixodidae (hard surveillance and diagnosis, but the growing U.S. population ticks) comprising approximately 700 species and 13 gen- and the spread of human communities into previously era; (ii) Argasidae (soft ticks), which consists of approxi- undeveloped environments also increase the regions of mately 180 species and 5 genera; and (iii) Nuttaliellidae, tick-human contact. which is composed of only one species and is found only Since the identification of Borrelia burgdorferi as in Africa (1, 2). the causative agent of Lyme disease in 1982, 11 tick- Ticks are major vectors of arthropod-borne infections and borne human bacterial pathogens have now been described not only can transmit a wide variety of pathogens, such as throughout Europe. -

Association of Helicobacter Pylori with Gastroduodenal Diseases

Jpn. J. Infect. Dis., 52, 183-197, 1999 Invited Review Association of Helicobacter pylori with Gastroduodenal Diseases Yoshikazu Hirai*, Shunji Hayashi, Hirofumi Shimomura, Keiji Ogumal and Kenji Yokotal Department of Microbiology, Jichi Medical School, Yakushiji 3311 -1 , Minamikawachi-machi, Kawachi-gun, Tochigi 329-0498 and JDepartment of Bacteriology, Okayama UniversityMedical School, Shikata-cho 2-5-1 , Okayama 700-8558, Japan (Received October 22, 1999) SUMMARY: Helicobacter pylori was first cultured in vitro in 1982・ This bacterium is a spiral gram-negative rod which grows under microaerophilic conditions・ The ecological● niche is the mucosa bf the human stomach which had been thought to be aseptic before the discovery of this bacterium・ This organism causes a long-lasting infection throughout a person's life if there is no medical intervention・ Numerous persons are infected with the organism around the world, and the rate of infection in Japan is nearly 50% of the population・ However, the route of infection remains unclear because the organism has not been isolatedfromany environment other thanseveral animals・ H・ pylori is now recognlZed● as a causative agent of gastritis and peptic ulcers・ Though gastritis, and especially chronic active gastritis, is observed at least histologlCally● in all persons with H. pylori, peptic ulcers develop ln● Only some infectedpersons. Specific factors in the host and/Or the bacteria are needed for the development of peptic ulcer disease・ Furthermore, H・ pylori is considered to be related to the development of gastric mucosa- associated lymphoid tissue (MAIJ) lymphoma, especially those of low grade. Also, H. pylori infection is a major● determinant for initiating the sequence of events leading to gastric cancer・ In some patients with low-grade gastric MAIJ lymphoma, the eradication of H. -

Flavodoxins As Novel Therapeutic Targets Against Helicobacter Pylori and Other Gastric Pathogens

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Review Flavodoxins as Novel Therapeutic Targets against Helicobacter pylori and Other Gastric Pathogens Sandra Salillas 1,2,3 and Javier Sancho 1,2,3,* 1 Biocomputation and Complex Systems Physics Institute (BIFI)-Joint Units: BIFI-IQFR (CSIC) and GBsC-CSIC, University of Zaragoza, 50018 Zaragoza, Spain; [email protected] 2 Departamento de Bioquímica y Biología Molecular y Celular, Facultad de Ciencias, University of Zaragoza, 37009 Zaragoza, Spain 3 Aragon Health Research Institute (IIS Aragón), 50009 Zaragoza, Spain * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +34-976-761-286; Fax: +34-976-762-123 Received: 14 February 2020; Accepted: 6 March 2020; Published: 10 March 2020 Abstract: Flavodoxins are small soluble electron transfer proteins widely present in bacteria and absent in vertebrates. Flavodoxins participate in different metabolic pathways and, in some bacteria, they have been shown to be essential proteins representing promising therapeutic targets to fight bacterial infections. Using purified flavodoxin and chemical libraries, leads can be identified that block flavodoxin function and act as bactericidal molecules, as it has been demonstrated for Helicobacter pylori (Hp), the most prevalent human gastric pathogen. Increasing antimicrobial resistance by this bacterium has led current therapies to lose effectiveness, so alternative treatments are urgently required. Here, we summarize, with a focus on flavodoxin, opportunities for pharmacological intervention offered by the potential protein targets described for this bacterium and provide information on other gastrointestinal pathogens and also on bacteria from the gut microbiota that contain flavodoxin. The process of discovery and development of novel antimicrobials specific for Hp flavodoxin that is being carried out in our group is explained, as it can be extrapolated to the discovery of inhibitors specific for other gastric pathogens. -

Carcinogenic Bacterial Pathogen Helicobacter Pylori Triggers DNA Double-Strand Breaks and a DNA Damage Response in Its Host Cells

Carcinogenic bacterial pathogen Helicobacter pylori triggers DNA double-strand breaks and a DNA damage response in its host cells Isabella M. Tollera,1, Kai J. Neelsena,1, Martin Stegera, Mara L. Hartunga, Michael O. Hottigerb, Manuel Stuckib, Behnam Kalalic, Markus Gerhardc, Alessandro A. Sartoria, Massimo Lopesa,2, and Anne Müllera,2 aInstitute of Molecular Cancer Research and bInstitute of Veterinary Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, University of Zürich, 8057 Zürich, Switzerland; and cDepartment of Medicine, Technical University Munich, 81675 Munich, Germany Edited by Jeffrey W. Roberts, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, and approved July 28, 2011 (received for review January 24, 2011) The bacterial pathogen Helicobacter pylori chronically infects the protected from precancerous lesions, and the adoptive transfer of − human gastric mucosa and is the leading risk factor for the devel- CD4+CD25 effector T cells is sufficient to sensitize mice to opment of gastric cancer. The molecular mechanisms of H. pylori- Helicobacter-induced preneoplasia (10). associated gastric carcinogenesis remain ill defined. In this study, we In addition to the pathological effects of the Helicobacter- examined the possibility that H. pylori directly compromises the specific immune response on the gastric mucosa, several lines of genomic integrity of its host cells. We provide evidence that the evidence indicate that the bacteria may promote gastric carci- infection introduces DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) in primary nogenesis by jeopardizing the integrity and stability of their and transformed murine and human epithelial and mesenchymal host’s genome (12). H. pylori infection of cultured gastric epi- cells. The induction of DSBs depends on the direct contact of live thelial cells down-regulates the components of the mismatch bacteria with mammalian cells.