Mhtml:File://S:\Shared\Library\Fairy Tales\Andersen\Hans Christ

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hans Christian Andersen's Use of Anthropomorphismi

Hans Christian Andersen’s Use of Anthropomorphismi Julia Shore Paludan, Lecturer, Sapienza, University of Rome Abstract The topic of anthropomorphism in Hans Christian Andersen’s tales has been discussed with students in classes in Danish Language and Literature at Sapienza, University of Rome (La Sapienza, Università di Roma) both for the purpose of the translation of his works and for understanding the meanings of the imagery in the studied works. Anthropomorphism is a common theme in many of Hans Christian Andersen’s fairy tales. Andersen’s symbolic use of nature, household objects, trinkets, toys and even birds, is an important theme in many of his works. He bestows human emotions on animate and inanimate objects, such as love and envy, often with an added touch of humour or irony. Andersen conveys issues of often sombre or tragicomic content, sometimes through allegorical tales and myths, that although they are not necessarily easily translatable or culturally transferable, appeal universally to all generations and nationalities. Andersen’s personification of animals also provides a subtle disguise for graver issues such as loss, and the struggle for freedom. The use of anthropomorphism and symbolism also allows younger readers access to complex and universal issues. Introduction The topic of this paper arose from the teaching of Danish language and literature to students at Sapienza University of Rome. Using a number of Andersen’s works, the specific use and meanings of anthropomorphic imagery was introduced and discussed; both as how this imagery could be translated and understood in Italian, and what they evoked through themes such as love, desire and freedom. -

Andersen's Fairy Tales

HTTPS://THEVIRTUALLIBRARY.ORG ANDERSEN’S FAIRY TALES H. C. Andersen Table of Contents 1. The Emperor’s New Clothes 2. The Swineherd 3. The Real Princess 4. The Shoes of Fortune 1. I. A Beginning 2. II. What Happened to the Councillor 3. III. The Watchman’s Adventure 4. IV. A Moment of Head Importance—an Evening’s “Dramatic Readings”—a Most Strange Journey 5. V. Metamorphosis of the Copying-clerk 6. VI. The Best That the Galoshes Gave 5. The Fir Tree 6. The Snow Queen 7. Second Story. a Little Boy and a Little Girl 8. Third Story. of the Flower-garden at the Old Woman’s Who Understood Witchcraft 9. Fourth Story. the Prince and Princess 10. Fifth Story. the Little Robber Maiden 11. Sixth Story. the Lapland Woman and the Finland Woman 12. Seventh Story. What Took Place in the Palace of the Snow Queen, and What Happened Afterward. 13. The Leap-frog 14. The Elderbush 15. The Bell 16. The Old House 17. The Happy Family 18. The Story of a Mother 19. The False Collar 20. The Shadow 21. The Little Match Girl 22. The Dream of Little Tuk 23. The Naughty Boy 24. The Red Shoes THE EMPEROR’S NEW CLOTHES Many years ago, there was an Emperor, who was so excessively fond of new clothes, that he spent all his money in dress. He did not trouble himself in the least about his soldiers; nor did he care to go either to the theatre or the chase, except for the opportunities then afforded him for displaying his new clothes. -

Bicentenary Literary Adaptations of Hc Andersen

UDC 821.113.4 Rennesa Jessup Minnesota State University TRAVELING COMPANIONS: BICENTENARY LITERARY ADAPTATIONS OF H. C. ANDERSEN TALES Adaptation is broadly defined, encompassing the re-working of virtually any kind of text into virtually any other kind of text. Moreover, it frequently involves the re-mediation of texts into entirely new forms. Even so, seemingly simple text-to- text adaptation of texts already frequently subject to adaptation can challenge both traditional and theoretical concepts of adaptation. Such was the case with a major Danish literary project undertaken in 2005. Danish State Railways, Dansk statsbaner (DSB) commissioned a series of adaptations of Hans Christian Andersen tales to be published in the DSB onboard magazine Ud & Se [Out & See] to commemorate the two-hundredth anniversary of H. C. Andersen’s birth. Resulting from the project were twelve original stories by twelve Danish authors: Pia Juul, Jan Sonnergaard, Ib Michael, Iselin Hermann, Preben Major Sørensen, Suzanne Brøgger, Bent Vinn Nielsen, Peter Laugesen, Kristian Ditlev Jensen, Lars Frost, Erling Jepsen, and Naja Marie Aidt. Each author adapted a different Andersen work, ranging from classics including “Den grimme ælling” [The Ugly Duckling], “Den lille havfrue” [The Little Mermaid], and “Kejserens nye klæder” [The Emperor’s New Clothes], to more obscure works such as “Dandse, dandse dukke min!” [Dance, Dance, My Doll!]. Issued in book form as Reisekammeraten og andre H. C. Andersen-historier i nye klæder [The Traveling Companion and Other H. C. Andersen Tales in New Clothes] (Copenhagen, 2005), the collection demonstrates a wide range of approaches to adaptation that seem to stretch the definition of adaptation to its limits. -

An Agnostic Family's Christmas

Tivoli Gardens and Hans Christian Andersen: A Tale of Confluence Story-based amusement parks and literary playgrounds are now coming into their own as witnessed by the tremendous success of the Wizarding World of Harry Potter, which is now the most popular attraction at Universal Orland. However, the history of story-based amusement parks can be traced back to 1843 with the opening of Tivoli Gardens in Copenhagen. Initially intended to function as a “pleasure garden” for the residents of Copenhagen, Tivoli Gardens gradually came to be associated with fairy tales in part because of the influence of Hans Christian Andersen. An examination of this history shows that Tivoli Gardens had an impact on Andersen’s fairy tales while Andersen’s fairy tales had an impact on the development of Tivoli Gardens. In many ways, this is a tale of confluence. The founder of Tivoli Gardens, Georg Carstensen, and Andersen knew each other through business connections, and Andersen followed Carstensen’s plans to build Tivoli Gardens. Andersen took a special interest in Carstensen’s plan to include a Chinese pavilion as one of the attractions. Andersen visited Tivoli Gardens during its first season, and he especially liked the whimsical Chinese pavilion, which was designed by the Danish architect H. C. Stilling. Inspired by this visit, Andersen wrote an original fairy tale titled “The Nightingale.” Andersen set this fairy tale in China, and he used the Tivoli Garden’s Chinese pavilion as the model for the Emperor’s palace. Over the history of Tivoli Gardens, Andersen’s fairy tales became incorporated into the park’s programing and attractions. -

O X Fo Rd Reading Cir C

6 SECOND EDITION EADIN R G D C R I O R F C L X E O N H I C G H R O U L B A S S R H O O H R R E S B A I U R G H • C L Teaching Guide 1 Contents Introduction iv 1. Birthday Presents—Lynne Reid Banks 1 2. Sky, Sea, Shore—James Reeves 6 3. Daedulus and Icarus 11 4. The Golden Crab—Andrew Lang 17 5. Eldorado—Edgar Allan Poe 24 6. The Selfish Giant—Oscar Wilde 30 7. The Snake—Emily Dickinson 37 8. Dear Diary 42 9. The Clockwork Mouse—Dick King-Smith 47 10. Robinson Crusoe’s Story—Charles E. Carryl 54 11. The Flying Trunk—Hans Christian Andersen 59 12. Rice-bowl Wishes—Bernadette and Dr Donald 65 13. The Walrus and The Carpenter—Lewis Carroll 71 14. Thank you, Ma’am—Langston Hughes 77 15. The Window 83 16. Weaver 88 17. The Magic Shop—H. G. Wells 92 18. A Passing Glimpse—Robert Lee Frost 98 19. The Hayloft—George MacDonald 104 20. Slow Dance—David L. Weatherford 110 21. The Treasure Seekers—Edith Nesbit 114 iii 1 Introduction The Teaching Guides of Oxford Reading Circle provide some guidelines for the help of the teacher in the classroom. This Teaching Guide includes: • an introduction on how to use Oxford Reading Circle in class. • suggestions for pre-reading tasks or warm-ups to the main lesson. • suggestions for while reading tasks with in-text questions. • suggestions for post-reading activities, based on basic concepts of literature presented progressively with respect to difficulty level within and across each grade. -

The Junior Classics, Volume 1

The Junior Classics, Volume 1 Willam Patten The Junior Classics, Volume 1 Table of Contents The Junior Classics, Volume 1.................................................................................................................................1 Willam Patten.................................................................................................................................................2 INTRODUCTION.........................................................................................................................................5 PREFACE......................................................................................................................................................7 MANABOZHO, THE MISCHIEF−MAKER................................................................................................9 WHY THE WOODPECKER HAS RED HEAD FEATHERS...................................................................12 WHY THE DIVER DUCK HAS SO FEW TAIL FEATHERS..................................................................14 MANAIBOZHO IS CHANGED INTO A WOLF......................................................................................15 MANABOZHO IS ROBBED BY THE WOLVES.....................................................................................17 MANABOZHO AND THE WOODPECKERS..........................................................................................18 THE BOY AND THE WOLVES................................................................................................................20 -

Thumbelina CD Booklet

Hans Christian Andersen THUMBELINA AND OTHER FAIRY TALES JUNIOR Read by finalists of the Voice of the Year competition CLASSICS UNABRIDGED CHILDREN’S FAVOURITES NA233512D 1 Thumbelina read by Eleanor Buchan 2:56 2 One night while she lay in her pretty bed… 3:36 3 Thumbelina sailed past many towns… 3:52 4 Near the wood in which she’d been living… 4:12 5 Thumbelina said nothing… 3:26 6 Very soon the springtime came… 2:54 7 When autumn arrived… 3:06 8 At length they reached the warm countries… 4:59 9 The Brave Tin Soldier read by Bob Rollett 2:54 10 When evening came… 3:23 11 Suddenly there appeared a great water-rat… 5:00 12 The Princess and the Pea read by Helen Davies 3:10 13 The Butterfly read by Michael Head 4:32 14 Spring went by… 3:31 15 The Flea and the Professor read by Richard Cuthbertson 3:14 16 The Professor was proud of the flea… 2:54 17 The flea lived with the princess… 4:56 18 The Flying Trunk read by Paul Rew 4:22 19 Then he flew away to the town… 4:14 20 Then the saucepan went on with his story… 5:27 2 21 The Metal Pig read by Howard Wolfin 5:23 22 As they passed from hall to hall… 4:34 23 It was morning… 5:10 24 Giuseppe went out the next morning… 3:25 25 When evening came and the house door… 4:12 26 Oh what beautiful pictures these were… 5:11 27 The Storks read by Helen Davies 2:51 28 The next day when the children… 2:59 29 Time passed on and the young storks… 3:45 30 Of all the boys in the street… 3:38 31 The Silver Shilling read by Julian McDonnell 3:27 32 Now begins the story as it was afterwards… 5:38 33 A year passed… -

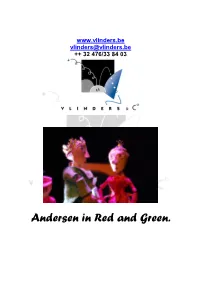

Nice to Know About Andersen in Red and Green

www.vlinders.be [email protected] ++ 32 476/33 84 03 Andersen in Red and Green. Andersen in Red and Green : nice to know - It are two fairy tales but performed not on the classical way - Figurentheater Vlinders & C° chooses for this performance a modern way of manipulation: stop motion puppets. - The prince and the princess are in both tales the same, in the original from Andersen they are not. - The prince loves green so he lives in a green world and castle. - The emperor and his daughter the princess prefer red so in their World everything has ‘something’ red. - So the performance is called: Andersen in Red and Green. - The prince and the princess have a servant, who serves them. The prince has a very joyfully optimistic servant. The princess has a reserved, rigid servant. Both servants are good friends, something our prince and princess don’t know. Special in the performance: both servants are acted by…the solo puppeteer. - The prince and the princess. - - The emperor and some princesses. - - The ladies in waiting About Andersen in Red and Green What happens when two world renowned figures players Dimitar Dimitrov (Bulgaria) and Ronny Aelbrecht (Belgium / Vlinders & C º) along step along into the magical world of the most famous Dane ever: Hans Christian Andersen? Then you will see two famous fairy tales of Andersen: The swineherd and the Princess on the Pea, merge into a story almost without words but with the same prince and princess! The solo puppeteer/servant serves this wonderful show for you in his world of red and green, supported by tingling music. -

Reading the Fairytales of Hans Christian Andersen and the Novels

The Bridge Volume 30 Number 2 Article 7 2007 Reading the Fairytales of Hans Christian Andersen and the Novels of Horatio Alger as Proto-Entrepreneurial Narrative or A true story of two boys who grew up to write stories which shaped the entrepreneurial attitude of their nations! Robert Smith Helle Neergaard Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/thebridge Part of the European History Commons, European Languages and Societies Commons, and the Regional Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Smith, Robert and Neergaard, Helle (2007) "Reading the Fairytales of Hans Christian Andersen and the Novels of Horatio Alger as Proto-Entrepreneurial Narrative or A true story of two boys who grew up to write stories which shaped the entrepreneurial attitude of their nations!," The Bridge: Vol. 30 : No. 2 , Article 7. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/thebridge/vol30/iss2/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Bridge by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Reading the Fairytales of Hans Christian Andersen and the Novels of Horatio Alger as Proto-Entrepreneurial Narrative or A true story of two boys who grew up to write stories which shaped the entrepreneurial attitude of their nations! by Robert Smith and Helle Neergaard • nee upon a time, long ago, in the slums of Odense in the State of Denmark there lived a poor boy whose ambition it was to write stories. His name was Hans Christian Andersen, a Cobblers son. -

Hans Christian Andersen and The

Final Syllabus Hans Christian Andersen and the Danish Golden Age Copenhagen Spring Semester 17, European Humanities 3-credit course Monday & Thursday 13.15-14.35 in classroom N7-C24 Major Disciplines: Literature Instructor: Janis Granger Ph. D., Scandinavian Languages and Literatures, University of California – Berkeley, 1981; M.A., Scandinavian Studies, University of California – Los Angeles, 1976; B.A., History, University of California – Berkeley. Lecturer in Danish Language, Literature and Culture, University of Wisconsin - Madison, 1981-1984. Written articles and reviews on Danish literature and Scandinavian Crime Fiction. With DIS since 1984 as faculty, Academic Counselor and Registrar; as of 2011 as full time faculty. Taught at DIS Stockholm for Fall Semester 2016. Office hours: by appointment, available before and after class DIS contacts: Matt Kelley, Program Assistant, European Humanities Department Hans Christian Andersen and the Danish Golden Age| DIS – Study Abroad in Scandinavia | Major Disciplines: Literature Final Syllabus Content This course will be a study of approximately 30 fairy tales by Hans Christian Andersen (1805- 75) as well as extracts from his travelogues, poems, diaries and his autobiography, The Fairy Tale of My Life. Andersen’s significance as an international storyteller will be emphasized by analyzing his tales using various approaches and by seeing different perceptions of him through the eyes of his contemporaries and his readers of today. In order to get a feel for Hans Christian Andersen’s world, we will familiarize ourselves with important figures of the Danish Golden Age (1800-1850). Andersen’s fairytales will provide the backbone for this course that will emphasize his genuine inventiveness and the complexity of his texts. -

Key Motifs in Oscar Wilde´S and H. C. Andersen´S Fairy Tales

Jihočeská univerzita v Českých Budějovicích Pedagogická fakulta Katedra anglistiky Bakalářská práce Key Motifs in Oscar Wilde´s and H. C. Andersen´s Fairy Tales Klíčové motivy v pohádkách Oscara Wilda a Hanse Christiana Andersena Vypracovala: Kateřina Vomastková, AJ-NJ, 3. ročník Vedoucí práce: PhDr. Alice Sukdolová, Ph.D. České Budějovice 2019 Prohlašuji, že svoji bakalářskou práci jsem vypracovala samostatně pouze s použitím pramenů a literatury uvedených v seznamu citované literatury. Prohlašuji, že v souladu s § 47b zákona č. 111/1998 Sb. v platném znění souhlasím se zveřejněním své bakalářské práce, a to v nezkrácené podobě elektronickou cestou ve veřejně přístupné části databáze STAG provozované Jihočeskou univerzitou v Českých Budějovicích na jejích internetových stránkách, a to se zachováním mého autorského práva k odevzdanému textu této kvalifikační práce. Souhlasím dále s tím, aby toutéž elektronickou cestou byly v souladu s uvedeným ustanovením zákona č. 111/1998 Sb. zveřejněny posudky školitele a oponentů práce i záznam o průběhu a výsledku obhajoby kvalifikační práce. Rovněž souhlasím s porovnáním textu mé kvalifikační práce s databází kvalifikačních prací Theses.cz provozovanou Národním registrem vysokoškolských kvalifikačních prací a systémem na odhalování plagiátů. V Českých Budějovicích dne 24. 4. 2019 Kateřina Vomastková Poděkování Ráda bych tímto poděkovala paní PhDr. Alici Sukdolové, Ph.D. za vedení mé bakalářské práce, za její cenné rady, připomínky, trpělivost a ochotu. Dále bych chtěla poděkovat své rodině za jejich podporu. Acknowledgement With this, I would like to sincerely thank PhDr. Alice Sukdolová, Ph.D. for the supervision of my final thesis, for her invaluable help, comments, patience and helpfulness. Additionally, I would like to thank my family for their support. -

H.C. Andersen and the Forgotten Manuscript When Does H.C

THE ADVENTURES OF YOUNG H.C. Andersen and the Forgotten Manuscript When does H.C. write his first story? What happened to it? Read The Adventures of Young H.C. Andersen and the Forgotten Manuscript to find out! QUESTIONS 1. H.C.’s father gifts Karen with ... c. The floorboards a. Bowling shoes d. The closet in his bedroom b. Red boots 4. The H.C. Andersen Museum is in ... c. Snorkeling fins d. Yellow slippers a. Odense, Denmark b. Tokyo, Japan 2. When the ghost of H.C. goes into the c. Cairo, Egypt sewer below his house, he discovers the d. Mexico City, Mexico ghost of ... 5. Why does H.C.’s mother think it’s a bad a. Karen idea for him to act in the play? b. Pierre c. Heinz 6. Why doesn’t H.C. wear his hat during d. Walt Disney the play? 3. Pierre sees H.C. hide his manuscript in ... a. The kitchen cabinets b. The backyard TRUE OR FALSE? _____ 1. H.C. plays the part of a sunflower _____ 5. “The Pine Tree” is the story of an in the performance. emperor and talented bird who live amongst gardens and flowers _____ 2. H.C. writes his first manuscript in and lights as beautiful as those at honor of his father. Tivoli. _____ 3. Karen joins the acting troupe and _____ 6. H.C. escapes from the evil theater travels to Italy. director via a trunk. This scene was inspired by the fairytale “The _____ 4. H.C.’s forgiveness frees Pierre Red Shoes.” from the sewer.