Hans Christian Andersen's Use of Anthropomorphismi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bicentenary Literary Adaptations of Hc Andersen

UDC 821.113.4 Rennesa Jessup Minnesota State University TRAVELING COMPANIONS: BICENTENARY LITERARY ADAPTATIONS OF H. C. ANDERSEN TALES Adaptation is broadly defined, encompassing the re-working of virtually any kind of text into virtually any other kind of text. Moreover, it frequently involves the re-mediation of texts into entirely new forms. Even so, seemingly simple text-to- text adaptation of texts already frequently subject to adaptation can challenge both traditional and theoretical concepts of adaptation. Such was the case with a major Danish literary project undertaken in 2005. Danish State Railways, Dansk statsbaner (DSB) commissioned a series of adaptations of Hans Christian Andersen tales to be published in the DSB onboard magazine Ud & Se [Out & See] to commemorate the two-hundredth anniversary of H. C. Andersen’s birth. Resulting from the project were twelve original stories by twelve Danish authors: Pia Juul, Jan Sonnergaard, Ib Michael, Iselin Hermann, Preben Major Sørensen, Suzanne Brøgger, Bent Vinn Nielsen, Peter Laugesen, Kristian Ditlev Jensen, Lars Frost, Erling Jepsen, and Naja Marie Aidt. Each author adapted a different Andersen work, ranging from classics including “Den grimme ælling” [The Ugly Duckling], “Den lille havfrue” [The Little Mermaid], and “Kejserens nye klæder” [The Emperor’s New Clothes], to more obscure works such as “Dandse, dandse dukke min!” [Dance, Dance, My Doll!]. Issued in book form as Reisekammeraten og andre H. C. Andersen-historier i nye klæder [The Traveling Companion and Other H. C. Andersen Tales in New Clothes] (Copenhagen, 2005), the collection demonstrates a wide range of approaches to adaptation that seem to stretch the definition of adaptation to its limits. -

An Agnostic Family's Christmas

Tivoli Gardens and Hans Christian Andersen: A Tale of Confluence Story-based amusement parks and literary playgrounds are now coming into their own as witnessed by the tremendous success of the Wizarding World of Harry Potter, which is now the most popular attraction at Universal Orland. However, the history of story-based amusement parks can be traced back to 1843 with the opening of Tivoli Gardens in Copenhagen. Initially intended to function as a “pleasure garden” for the residents of Copenhagen, Tivoli Gardens gradually came to be associated with fairy tales in part because of the influence of Hans Christian Andersen. An examination of this history shows that Tivoli Gardens had an impact on Andersen’s fairy tales while Andersen’s fairy tales had an impact on the development of Tivoli Gardens. In many ways, this is a tale of confluence. The founder of Tivoli Gardens, Georg Carstensen, and Andersen knew each other through business connections, and Andersen followed Carstensen’s plans to build Tivoli Gardens. Andersen took a special interest in Carstensen’s plan to include a Chinese pavilion as one of the attractions. Andersen visited Tivoli Gardens during its first season, and he especially liked the whimsical Chinese pavilion, which was designed by the Danish architect H. C. Stilling. Inspired by this visit, Andersen wrote an original fairy tale titled “The Nightingale.” Andersen set this fairy tale in China, and he used the Tivoli Garden’s Chinese pavilion as the model for the Emperor’s palace. Over the history of Tivoli Gardens, Andersen’s fairy tales became incorporated into the park’s programing and attractions. -

O X Fo Rd Reading Cir C

6 SECOND EDITION EADIN R G D C R I O R F C L X E O N H I C G H R O U L B A S S R H O O H R R E S B A I U R G H • C L Teaching Guide 1 Contents Introduction iv 1. Birthday Presents—Lynne Reid Banks 1 2. Sky, Sea, Shore—James Reeves 6 3. Daedulus and Icarus 11 4. The Golden Crab—Andrew Lang 17 5. Eldorado—Edgar Allan Poe 24 6. The Selfish Giant—Oscar Wilde 30 7. The Snake—Emily Dickinson 37 8. Dear Diary 42 9. The Clockwork Mouse—Dick King-Smith 47 10. Robinson Crusoe’s Story—Charles E. Carryl 54 11. The Flying Trunk—Hans Christian Andersen 59 12. Rice-bowl Wishes—Bernadette and Dr Donald 65 13. The Walrus and The Carpenter—Lewis Carroll 71 14. Thank you, Ma’am—Langston Hughes 77 15. The Window 83 16. Weaver 88 17. The Magic Shop—H. G. Wells 92 18. A Passing Glimpse—Robert Lee Frost 98 19. The Hayloft—George MacDonald 104 20. Slow Dance—David L. Weatherford 110 21. The Treasure Seekers—Edith Nesbit 114 iii 1 Introduction The Teaching Guides of Oxford Reading Circle provide some guidelines for the help of the teacher in the classroom. This Teaching Guide includes: • an introduction on how to use Oxford Reading Circle in class. • suggestions for pre-reading tasks or warm-ups to the main lesson. • suggestions for while reading tasks with in-text questions. • suggestions for post-reading activities, based on basic concepts of literature presented progressively with respect to difficulty level within and across each grade. -

The Junior Classics, Volume 1

The Junior Classics, Volume 1 Willam Patten The Junior Classics, Volume 1 Table of Contents The Junior Classics, Volume 1.................................................................................................................................1 Willam Patten.................................................................................................................................................2 INTRODUCTION.........................................................................................................................................5 PREFACE......................................................................................................................................................7 MANABOZHO, THE MISCHIEF−MAKER................................................................................................9 WHY THE WOODPECKER HAS RED HEAD FEATHERS...................................................................12 WHY THE DIVER DUCK HAS SO FEW TAIL FEATHERS..................................................................14 MANAIBOZHO IS CHANGED INTO A WOLF......................................................................................15 MANABOZHO IS ROBBED BY THE WOLVES.....................................................................................17 MANABOZHO AND THE WOODPECKERS..........................................................................................18 THE BOY AND THE WOLVES................................................................................................................20 -

Thumbelina CD Booklet

Hans Christian Andersen THUMBELINA AND OTHER FAIRY TALES JUNIOR Read by finalists of the Voice of the Year competition CLASSICS UNABRIDGED CHILDREN’S FAVOURITES NA233512D 1 Thumbelina read by Eleanor Buchan 2:56 2 One night while she lay in her pretty bed… 3:36 3 Thumbelina sailed past many towns… 3:52 4 Near the wood in which she’d been living… 4:12 5 Thumbelina said nothing… 3:26 6 Very soon the springtime came… 2:54 7 When autumn arrived… 3:06 8 At length they reached the warm countries… 4:59 9 The Brave Tin Soldier read by Bob Rollett 2:54 10 When evening came… 3:23 11 Suddenly there appeared a great water-rat… 5:00 12 The Princess and the Pea read by Helen Davies 3:10 13 The Butterfly read by Michael Head 4:32 14 Spring went by… 3:31 15 The Flea and the Professor read by Richard Cuthbertson 3:14 16 The Professor was proud of the flea… 2:54 17 The flea lived with the princess… 4:56 18 The Flying Trunk read by Paul Rew 4:22 19 Then he flew away to the town… 4:14 20 Then the saucepan went on with his story… 5:27 2 21 The Metal Pig read by Howard Wolfin 5:23 22 As they passed from hall to hall… 4:34 23 It was morning… 5:10 24 Giuseppe went out the next morning… 3:25 25 When evening came and the house door… 4:12 26 Oh what beautiful pictures these were… 5:11 27 The Storks read by Helen Davies 2:51 28 The next day when the children… 2:59 29 Time passed on and the young storks… 3:45 30 Of all the boys in the street… 3:38 31 The Silver Shilling read by Julian McDonnell 3:27 32 Now begins the story as it was afterwards… 5:38 33 A year passed… -

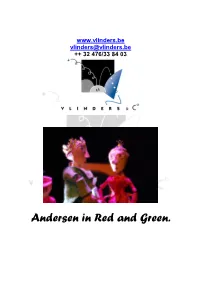

Nice to Know About Andersen in Red and Green

www.vlinders.be [email protected] ++ 32 476/33 84 03 Andersen in Red and Green. Andersen in Red and Green : nice to know - It are two fairy tales but performed not on the classical way - Figurentheater Vlinders & C° chooses for this performance a modern way of manipulation: stop motion puppets. - The prince and the princess are in both tales the same, in the original from Andersen they are not. - The prince loves green so he lives in a green world and castle. - The emperor and his daughter the princess prefer red so in their World everything has ‘something’ red. - So the performance is called: Andersen in Red and Green. - The prince and the princess have a servant, who serves them. The prince has a very joyfully optimistic servant. The princess has a reserved, rigid servant. Both servants are good friends, something our prince and princess don’t know. Special in the performance: both servants are acted by…the solo puppeteer. - The prince and the princess. - - The emperor and some princesses. - - The ladies in waiting About Andersen in Red and Green What happens when two world renowned figures players Dimitar Dimitrov (Bulgaria) and Ronny Aelbrecht (Belgium / Vlinders & C º) along step along into the magical world of the most famous Dane ever: Hans Christian Andersen? Then you will see two famous fairy tales of Andersen: The swineherd and the Princess on the Pea, merge into a story almost without words but with the same prince and princess! The solo puppeteer/servant serves this wonderful show for you in his world of red and green, supported by tingling music. -

H.C. Andersen and the Forgotten Manuscript When Does H.C

THE ADVENTURES OF YOUNG H.C. Andersen and the Forgotten Manuscript When does H.C. write his first story? What happened to it? Read The Adventures of Young H.C. Andersen and the Forgotten Manuscript to find out! QUESTIONS 1. H.C.’s father gifts Karen with ... c. The floorboards a. Bowling shoes d. The closet in his bedroom b. Red boots 4. The H.C. Andersen Museum is in ... c. Snorkeling fins d. Yellow slippers a. Odense, Denmark b. Tokyo, Japan 2. When the ghost of H.C. goes into the c. Cairo, Egypt sewer below his house, he discovers the d. Mexico City, Mexico ghost of ... 5. Why does H.C.’s mother think it’s a bad a. Karen idea for him to act in the play? b. Pierre c. Heinz 6. Why doesn’t H.C. wear his hat during d. Walt Disney the play? 3. Pierre sees H.C. hide his manuscript in ... a. The kitchen cabinets b. The backyard TRUE OR FALSE? _____ 1. H.C. plays the part of a sunflower _____ 5. “The Pine Tree” is the story of an in the performance. emperor and talented bird who live amongst gardens and flowers _____ 2. H.C. writes his first manuscript in and lights as beautiful as those at honor of his father. Tivoli. _____ 3. Karen joins the acting troupe and _____ 6. H.C. escapes from the evil theater travels to Italy. director via a trunk. This scene was inspired by the fairytale “The _____ 4. H.C.’s forgiveness frees Pierre Red Shoes.” from the sewer. -

Teacher's Study Guide

Teacher's Study Guide What's big and fat and pink and loves to dress up in fancy clothes? Give up? It's the Emperor in Grey Seal Puppets' clever adaptation of The Emperor’s New Clothes. The beloved Hans Christian Andersen classic takes on a whole new dimension as it is transformed into a fable. The crafty tailors have become foxes; the prime minister a near-sighted camel; and the councillor, a befuddled old walrus. Even the audience will take part-- as animals, of course! Characters and costume designs were inspired by the illustrations of Janet Stevens in The Emperor’s New Clothes published by Holiday House. ABOUT THE EMPEROR’S NEW CLOTHES Grey Seal Puppets brings to life the beloved Hans Christian Anderson classic tale, The Emperor’s New Clothes. This familiar story takes an unusual twist in this version; it is told as a fable. A pompous pig, quite taken with his appearance, is the perfect Emperor; a nearsighted camel and a befuddled walrus serve as his courtiers and two conniving foxes from the "shady side" are con men bent on getting rich off the Emperor's vanity. It takes the innocence of a small bear cub, unafraid to say what she truly feels, to awaken the conscience of the entire village. The timeless moral of this tale is honesty, but it also warns against vanity and self-indulgence. The audience will recognize the Emperor as a vain ruler who easily falls for the foxes' story of a magic cloth. Those who can see the cloth are smart and good at what they do. -

Mhtml:File://S:\Shared\Library\Fairy Tales\Andersen\Hans Christ

Page 1 of 10 Title: Hans Christian Andersen (1869) Author(s): Georg Brandes Publication Details: Creative Spirits of the Nineteenth Century. Thomas Y. Crowell Company, 1923. p1-54. Source: Short Story Criticism. Ed. Thomas Votteler. Vol. 6. Detroit: Gale Research, 1990. From Literature Resource Center. Document Type: Critical essay, Excerpt Full Text: COPYRIGHT 1990 Gale Research, COPYRIGHT 2007 Gale, Cengage Learning Full Text: [An esteemed Danish literary critic and biographer, Brandes was the first prominent scholar to write extensively on Andersen. According to Elias Bredsdorff, Brandes was “the first scholar altogether who realised that Andersen's tales gave him an important and unique place in world literature and who saw that the tales themselves merited serious critical discussion.” In the following excerpt from an essay that is recognized as significant in Andersen scholarship, Brandes favorably assesses Andersen's tales, admiring in particular his ability to write as a child might think and speak.] To replace the accepted written language with the free, unrestrained language of familiar conversation, to exchange the more rigid form of expression of grown people for such as a child uses and understands, becomes the true goal of the author as soon as he embraces the resolution to tell nursery stories for children. He has the bold intention to employ oral speech in a printed work, he will not write but speak, and he will gladly write as a school-child writes, if he can thus avoid speaking as a book speaks. The written word is poor and insufficient, the oral has a host of allies in the expression of the mouth that imitates the object to which the discourse relates, in the movement of the hand that describes it, in the length or shortness of the tone of the voice, in its sharp or gentle, grave or droll character, in the entire play of the features, and in the whole bearing. -

Fairy Tales from Hans Christian Andersen;

Fairy /TalG3 Ulxislrdted by l)ugald 5te^arl WalUer Maleolm Whyte CoUection of CHILDREN'S LITERATURE CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY DATE DUE Uras-NOV'tt ^'^t^'<%<- ^^im^m -.zwmww^' ' i * i i,sdMih^&S!!^ y #) ijn w ii»» Cornell University Library PZ 8.A54 1914a Fairy tales from Hans Christian Andersen 3 1924 005 634 658 Cornell University v/J /ml Library The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924005634658 Fairy Tales From Hans Christian Andersen v^.^ 3 tiiij' The courtiers looked most s'l'Hnd and proper., . Numbers of little elves danced around the iiall ' ,.«•••»•#««*•••« *•.(*•*••»•**< EU:iT^TEP-Bf •PDQAE-myAKFWAIKEEc •Islewlfork" & George ' Sully ' ' Company CH\uOP-erv5'S> iL-L-O^V/if^TeD UTeRATOf^e Illustrations & Decorations Copyright, 1914, 62/ DOUBLEDAY, PaGE & COMPANT TO AVIS MY MOTHER I have never been anywhere except Richmond, Virginia, and New York, because I have always been told that only grown-up people were allowed to travel. But the good East Wind and the kindly Moon have taken me on rapturous journeys high above the world to get an enchanted view of things. In this book I have put some of my discoveries, but it you are looking here for real likeness of the things that any one could see if he were grown up, you had better close the covers now. You cannot expect me to draw an exact picture of the North Pole or of a Chinese lady's feet or of a sea-cucumber. -

The Harvard Classics Eboxed

HARVARD CLASSICS -THE FIVE-FOOT SHELFOFBOOKS OS Ell iiiQl QlllI] THE HARVARD CLASSICS The Five-Foot Shelf of Books throng peopf Tj-,'!-,' /.iirrv'nnr nut of the toicH In See hitn hanged V —Pogf 35-1 THE HARVARD CLASSICS EDITED BY CHARLES W. ELIOT, LL.D. Folk-Lore and Fable iEsop • Grimm Andersen W«/A \ntroductions and Urates \olume 17 P. F. Collier & Son Corporation NEW YORK Copyright, 1909 By p. F. Collier & Son MANUFACTUKED IN U. S. A. CONTENTS ^SOP'S FABLES— pace The Cock and the Pearl ii The Wolf and the Lamb ii The Dog and the Shadow 12 The Lion's Share 12 The Wolf and the Crane la The Man and the Serpent 13 The Town Mouse and the Country Mouse 13 The Fox and the Crow 14 The Sick Lion 14 The Ass and the Lapdog 15 The Lion and the Mouse 15 The Swallow and the Other Birds 16 The Frogs Desiring a King 16 The Mountains in Labour 17 The Hares and the Frogs 17 The Wolf and the Kid 18 The Woodman and the Serpent 18 The Bald Man and the Fly 18 The Fox and the Stork 19 The Fox and the Mask 19 The Jay and the Peacock 19 The Frog and the Ox 20 Androcles 20 The Bat, the Birds, and the Beasts 21 The Hart and the Hunter 21 The Serpent and the File 22 The Man and the Wood 22 The Dog and the Wolf 22 The Belly and the Members 23 The Hart in the Ox-Stall 23 The Fox and the Grapes 24 The Horse, Hunter, and Stag 24 The Peacock and Juno 24 The Fox and the Lion 25 I CONTENTS PAGE The Lion and the Statue 25 The Ant and the Grasshopper 25 The Tree and the Reed 26 The Fox and the Cat 26 The Wolf in Sheep's Clothing 27 The Dog in the Manger 27 The Man and -

Fiction and Story

ACC.NO. AUTHOR'S NAME TITLE OF BOOKS PUBLISHER 96 Bhatt , Bhashkerbhai Birbal The Wise Navneet : Mumbai 97 Bhatt , Bhashkerbhai Birbal The Wise Navneet : Mumbai 98 Bhatt , Bhashkerbhai Birbal The Wise Navneet : Mumbai 99 Bhatt , Bhashkerbhai Birbal The Wise Navneet : Mumbai 100 Bhatt , Bhashkerbhai Birbal The Wise Navneet : Mumbai 101 Joshi , Yogesh Huumorous Tales Of Tenalirama Navneet : Mumbai 102 Joshi , Yogesh Huumorous Tales Of Tenalirama Navneet : Mumbai 103 Joshi , Yogesh Huumorous Tales Of Tenalirama Navneet : Mumbai 104 Joshi , Yogesh Huumorous Tales Of Tenalirama Navneet : Mumbai 105 Joshi , Yogesh Huumorous Tales Of Tenalirama Navneet : Mumbai 106 Joshi , Yogesh Huumorous Tales Of Tenalirama Navneet : Mumbai Let'S See & Say : The Story Of Puss 109 Dhawan , Kiran Ill Book Place And Boots Let'S See & Say : The Story Of Puss 110 Dhawan , Kiran Ill Book Place And Boots Let'S See & Say : The Story Of Puss 111 Dhawan , Kiran Ill Book Place And Boots Let'S See & Say ;The Story Of The 112 Dhawan , Kiran Ill Book Place Musician Of Breman Let'S See & Say ;The Story Of The 113 Dhawan , Kiran Ill Book Place Musician Of Breman 114 Dhawan , Kiran Ill Let'S See & Say ; The Ugly Duckling Book Place 115 Dhawan , Kiran Ill Let'S See & Say ; The Ugly Duckling Book Place Let'S See & Say ; Little Red Riding 116 Dhawan , Kiran Ill Book Place Hood Let'S See & Say ; Ali Baba & The 117 Dhawan , Kiran Ill Book Place Fourty Thieves Let'S See & Say ; Snow Whitw & 118 Dhawan , Kiran Ill Book Place The 7 Dwarfs Let'S See & Say ;The Story Of The 119 Dhawan , Kiran Ill Book Place Musician Of Breman 120 Sharma , Reita The Pied Piper Of Hamalin D.S.