Geographical Representation Under Proportional Representation: the Cases of Israel and the Netherlands

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Detailed Proposal for a Feasible Electoral Reform

Improving the Accountability and Stability of Israel’s Political System: A Detailed Proposal for a Feasible Electoral Reform Abraham Diskin & Emmanuel Navon August 2015 Page 1 of 58 Table of Contents Executive Summary Page 3 Part 1: Purpose and Goals of Electoral Reform Page 5 Part 2: Mechanism for the Implementation of the Proposed Reforms Page 7 Part 3: Means for Achieving the Goals of Electoral Reform Page 10 Appendix 1: History of Israel’s Voting System and Electoral Reforms Page 15 Appendix 2: Example of Voting Ballot for Election-day Primaries Page 19 Appendix 3: Comparative Study of Electoral Systems Page 20 Appendix 4: Regional Elections Page 23 Appendix 5: Mechanisms for Appointing a Government Page 30 Appendix 6: Duration of Israeli Governments Page 33 Appendix 7: Correlation of the Number of Parties and Political Stability Page 39 Appendix 8: Results of Knesset Elections, 1949-2015 Page 42 Appendix 9: Opinion Poll on the Proposed Reforms Page 53 Bibliography Page 56 Page 2 of 58 Executive Summary This paper is a detailed proposal for the reform of Israel’s electoral system. The changes proposed here are the result of years of research, of data analysis, and of comparative studies. We believe that the reforms outlined in this paper would be beneficial, that they would have a realistic chance of being implemented, and that they would strike a delicate balance between conflicting agendas. The proposed reform is meant to achieve the following overall goals: a. To make Members of Knesset (MKs) more accountable and answerable to their voters; b. To improve government stability. -

Inequality, Identity, and the Long-Run Evolution of Political Cleavages in Israel 1949-2019

WID.world WORKING PAPER N° 2020/17 Inequality, Identity, and the Long-Run Evolution of Political Cleavages in Israel 1949-2019 Yonatan Berman August 2020 Inequality, Identity, and the Long-Run Evolution of Political Cleavages in Israel 1949{2019 Yonatan Berman∗ y August 20, 2020 Abstract This paper draws on pre- and post-election surveys to address the long run evolution of vot- ing patterns in Israel from 1949 to 2019. The heterogeneous ethnic, cultural, educational, and religious backgrounds of Israelis created a range of political cleavages that evolved throughout its history and continue to shape its political climate and its society today. De- spite Israel's exceptional characteristics, we find similar patterns to those found for France, the UK and the US. Notably, we find that in the 1960s{1970s, the vote for left-wing parties was associated with lower social class voters. It has gradually become associated with high social class voters during the late 1970s and later. We also find a weak inter-relationship between inequality and political outcomes, suggesting that despite the social class cleavage, identity-based or \tribal" voting is still dominant in Israeli politics. Keywords: Political cleavages, Political economy, Income inequality, Israel ∗London Mathematical Laboratory, The Graduate Center and Stone Center on Socio-Economic Inequality, City University of New York, [email protected] yI wish to thank Itai Artzi, Dror Feitelson, Amory Gethin, Clara Mart´ınez-Toledano, and Thomas Piketty for helpful discussions and comments, and to Leah Ashuah and Raz Blanero from Tel Aviv-Yafo Municipality for historical data on parliamentary elections in Tel Aviv. -

The Success of an Ethnic Political Party: a Case Study of Arab Political Parties in Israel

University of Mississippi eGrove Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors Theses Honors College) 2014 The Success of an Ethnic Political Party: A Case Study of Arab Political Parties in Israel Samira Abunemeh University of Mississippi. Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Abunemeh, Samira, "The Success of an Ethnic Political Party: A Case Study of Arab Political Parties in Israel" (2014). Honors Theses. 816. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis/816 This Undergraduate Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College) at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Success of an Ethnic Political Party: A Case Study of Arab Political Parties in Israel ©2014 By Samira N. Abunemeh A thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for completion Of the Bachelor of Arts degree in International Studies Croft Institute for International Studies Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College The University of Mississippi University, Mississippi May 2014 Approved: Dr. Miguel Centellas Reader: Dr. Kees Gispen Reader: Dr. Vivian Ibrahim i Abstract The Success of an Ethnic Political Party: A Case Study of Arab Political Parties in Israel Israeli Arab political parties are observed to determine if these ethnic political parties are successful in Israel. A brief explanation of four Israeli Arab political parties, Hadash, Arab Democratic Party, Balad, and United Arab List, is given as well as a brief description of Israeli history and the Israeli political system. -

Strategic and Non-Policy Voting: a Coalitional Analysis of Israeli

Strategic and Non-policy Voting: A Coalitional Analysis of Israeli Electoral Reform Ethan Bueno de Mesquita Department of Government Harvard University Forthcoming in Comparative Politics, October 2000. Strategic and Non-policy Voting: A Coalitional Analysis of Israeli Electoral Reform Abstract I examine why a majority of Israel’s legislators voted for direct election of the prime minister, reforming the electoral system that vested them with power. The analysis incorporates coalitional politics, strategic voting, and voter preferences over non-policy issues such as candidate charisma. The model generates novel hypotheses that are tested against empirical evidence. It explains five empirical puzzles that are not fully addressed by extant explanations: why Labour supported the reform, why Likud opposed it, why small left-wing parties supported the reform, small right-wing parties were split, and religious parties opposed it, why the Likud leadership, which opposed reform, lifted party discipline in the final reading of the bill, and why electoral reform passed at the particular time that it did. Strategic and Non-policy Voting: A Coalitional Analysis of Israeli Electoral Reform On March 18, 1992, Israel’s twelfth Knesset legislated the direct election of the Prime Minister, fundamentally altering Israel’s electoral system. Such large-scale electoral reform is rare in democracies.1 This is because electoral reform requires that those who have been vested with power by a particular system vote for a new system whose consequences are uncertain. Efforts to explain the political causes of Israeli electoral reform leave critical questions unanswered. A theory of electoral reform must explain both the interests of the political actors involved as well as why reform occurred at a particular time; it must specify the changes in the actors’ interests or in the political system that led to reform. -

Geographical Representation Under Proportional

CSD Center for the Study of Democracy An Organized Research Unit University of California, Irvine www.democ.uci.edu It is frequently assumed that proportional representation electoral systems do not provide geographical representation. For example, if we consider the literature on electoral reform, advocates of retaining single-member district plurality elections often cite the failure of proportional representation to give voters local representation (Norton, 1997; Hain, 1983; see Farrell, 2001). Even advocates of proportional representation often recognize the lack of district representation as a failure that has to be addressed by modifying their proposals (McLean, 1991; Dummett, 1997).1 However, there has been little empirical research into whether proportional representation elections produce results that are geographically representative. This paper considers geographical representation in two of the most “extreme” cases of proportional representation, Israel and the Netherlands. These countries have proportional representation with a single national constituency, and thus lack institutional features that force geographical representation. They are thus limiting cases, providing evidence of the type of geographical patterns we are likely to see when there are no institutions that enforce specific geographical patterns. We find that the legislatures of Israel and the Netherlands are surprisingly representative geographically, although not perfectly so. Furthermore, we find an interesting pattern. While the main metropolitan areas -

Women in the Knesset: Compilation of Data Following the Elections to the Twenty-Third Knesset

Women in the Knesset: Compilation of Data Following the Elections to the Twenty-third Knesset Written for International Women’s Day 2020 Review Written by: Ido Avgar and Etai Fiedelman Approved by: Orly Almagor Lotan Design and production: Knesset Printing and Publications Department Date: 12 Adar 5780, 8 March 2020 www.knesset.gov.il/mmm The Knesset Research and Information Center Women in the Knesset: Compilation of Data Following the Elections to the Twenty-third Knesset Table of Contents Summary ................................................................................................................................ 1 .1 Female Knesset Members over Time........................................................................ 3 .2 Female Candidates and Elected Members, Sixteenth–Twenty-third Knessets . 4 .3 The Twenty-third Knesset—Analysis by List ........................................................... 9 .4 Female Knesset Functionaries ................................................................................. 11 .5 Comparing Israel to the Rest of the World ............................................................ 15 .6 Quotas for the Fair Representation of Women in Political Parties .................... 17 6.1 The Situation in Israel ............................................................................................. 18 www.knesset.gov.il/mmm The Knesset Research and Information Center 1 | Women in the Knesset: Compilation of Data Following the Elections to the Twenty-third Knesset Summary This document -

The Representation of Women in Israeli Politics

10E hy is it important for women to be represented in the Perspective A Comparative Politics: in Israeli Women of Representation The WKnesset and in cabinet? Are women who are elected The Representation of to these institutions expected to do more to promote “female” interests than their male counterparts? What are the factors influencing the representation of women in Israeli politics? How Women in Israeli Politics has their representation changed over the years, and would the imposition of quotas be a good idea? A Comparative Perspective This policy paper examines the representation of women in Israeli politics from a comparative perspective. Its guiding premise is that women’s representation in politics, and particularly in legislative bodies, is of great importance in that it is tightly bound to liberal and democratic principles. According to some researchers, it is also important because female legislators Policy Paper 10E advance “female” issues more than male legislators do. While there has been a noticeable improvement in the representation of women in Israeli politics over the years, the situation in Israel is still fairly poor in this regard. This paper Assaf Shapira | Ofer Kenig | Chen Friedberg | looks at the impact of this situation on women’s status and Reut Itzkovitch-Malka gender equality in Israeli society, and offers recommendations for improving women’s representation in politics. The steps recommended are well-accepted in many democracies around the world, but have yet to be tried in Israel. Why is it important for women to be Assaf Shapira | Ofer Kenig | Chen Friedberg | Reut Itzkovitch-Malka Friedberg | Chen | Ofer Kenig Shapira Assaf This publication is an English translation of a policy paper represented in the Knesset and in cabinet? published in Hebrew in August 2013, which was produced by Are women who are elected to these the Israel Democracy Institute’s “Political Reform Project,” led by Prof. -

Legislative Election Results in Israel, 1949-2019

Chapter 19. "Inequality, Identity, and the Long-Run Evolution of Political Cleavages in Israel 1949-2019" Yonatan Berman Appendix: Figures, tables and raw results Main figures and tables Figure 1 Legislative election results in Israel, 1949-2019 Figure 2 Class cleavages in Israel, 1969-2019 Figure 3 Vote for right and left in Tel Aviv, Israel, 1949-2019 Figure 4 Residual identity component in Tel Aviv, Israel, 1981-2015 Figure 5 Vote for right-wing and left-wing parties among unemployed and inactive voters in Israel, 2003-2015 Figure 6 The educational cleavage in Israel, 1969-2019 Figure 7 Vote for right-wing parties among Sepharadic voters in Israel, 1969-2019 Figure 8 The religious cleavage in Israel, 1969-2019 Figure 9 The gender cleavage in Israel, 1969-2019 Appendix figures and tables Figure A1 General election results in Israel by bloc, 1949-2019 Figure A2 Income inequality in Israel, 1979-2015 Figure A3 Vote for left by social class (excluding center and Arab parties), 1969-2019 Figure A4 Vote for the Republican and Democratic candidates in New York City, 1948-2016 Figure A5 The effect of the 2003 reforms on left and right vote Figure A6 Share of voters by ethnicity and religiosity, 1969-2019 Table A1 Division of parties to blocks Table A2 The effect of the 2003 reforms on right vote Figure 18.1 - Legislative election results in Israel, 1949-2019 100% Right (Likud, Israel Beitenu, etc.) Left (Labor, Meretz, etc.) 90% Center (Kahol Lavan, etc.) Arab parties (Joint Arab List, etc.) 80% Ultra-orthodox (Shas, Yahadut HaTora, etc.) 70% 60% 50% 40% Share of votes (%) votes of Share 30% 20% 10% 0% 1949 1954 1959 1964 1969 1974 1979 1984 1989 1994 1999 2004 2009 2014 2019 Source: author's computations using official election results (see wpid.world). -

Health Systems in Transition Vol

Health Systems in Transition Vol. 11 No. 2 2009 Israel Health system review Bruce Rosen • Hadar Samuel Editor: Sherry Merkur Editorial Board Editor in chief Elias Mossialos, London School of Economics and Political Science, United Kingdom and European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies Editors Reinhard Busse, Berlin Technical University, Germany Josep Figueras, European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies Martin McKee, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, United Kingdom and European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies Richard Saltman, Emory University, United States Editorial team Sara Allin, European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies Cristina Hernandez Quevedo, European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies Anna Maresso, European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies David McDaid, European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies Sherry Merkur, European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies Philipa Mladovsky, European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies Bernd Rechel, European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies Erica Richardson, European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies Sarah Thomson, European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies International advisory board Tit Albreht, Institute of Public Health, Slovenia Carlos Alvarez-Dardet Díaz, University of Alicante, Spain Rifat Atun, Imperial College London, United Kingdom Johan Calltorp, Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions, Sweden Armin Fidler, The World Bank Colleen Flood, University of -

Iraq: Politics, Elections, and Benchmarks

Iraq: Politics, Elections, and Benchmarks Kenneth Katzman Specialist in Middle Eastern Affairs March 1, 2011 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RS21968 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Iraq: Politics, Elections, and Benchmarks Summary Iraq’s political system is increasingly characterized by peaceful competition and formation of cross-sectarian alliances, although ethnic and sectarian infighting continues, sometimes involving the questionable use of key levers of power and legal institutions. This infighting—and the belief that holding political power may mean the difference between life and death for the various political communities—significantly delayed agreement on a new government that was to be selected following the March 7, 2010, national elections for the Council of Representatives (COR, parliament). With U.S. intervention, on November 10, 2010, major ethnic and sectarian factions agreed on a framework for a new government, breaking the long deadlock. Their agreement, under which Prime Minister Nuri al-Maliki would serve another term, was implemented in the presentation by him of a broad-based cabinet on December 21, 2010, in advance of a December 25 constitutional deadline. The participation of all major factions in the new government is stabilizing politically and may have created political momentum to act on key outstanding legislation crucial to attracting foreign investment, such as national hydrocarbon laws. There may be early indications that the new government is acting on long-stalled initiatives, including year-long tensions over Kurdish exports of oil. Still, delayed action on improving key services, such as electricity, has created popular frustration that manifested as protests during February 2011, possibly inspired by the wave of unrest that has broken out in many other Middle Eastern countries. -

Iraq: Politics, Elections, and Benchmarks

Iraq: Politics, Elections, and Benchmarks Kenneth Katzman Specialist in Middle Eastern Affairs December 22, 2010 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RS21968 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Iraq: Politics, Elections, and Benchmarks Summary Iraq’s political system, the result of a U.S.-supported election process, has been increasingly characterized by peaceful competition, as well as by attempts to form cross-sectarian alliances. Ethnic and factional infighting continues, sometimes involving the questionable use of key levers of power and legal institutions. This infighting—and the belief that holding political power may mean the difference between life and death for the various political communities—significantly delayed agreement on a new government that was to be selected following the March 7, 2010, national elections for the Council of Representatives (COR, parliament). With U.S. intervention, on November 10, 2010, major ethnic and sectarian factions agreed on a framework for a new government, breaking the long deadlock. Iraqi leaders say agreement on a new cabinet is close, and Prime Minister Nuri al-Maliki, tapped to continue in that role, is expected to present his choices to the COR for approval on/about December 23, in advance of a December 25 constitutional deadline. The difficulty in reaching agreement had multiple causes that could still cause instability over the long term. Among the causes were the close election results. With the results certified, a mostly Sunni Arab-supported “Iraqiyya” slate of former Prime Minister Iyad al-Allawi unexpectedly gained a plurality of 91 of the 325 COR seats up for election. -

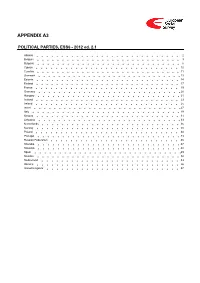

ESS6 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS6 - 2012 ed. 2.1 Albania 2 Belgium 3 Bulgaria 6 Cyprus 10 Czechia 11 Denmark 13 Estonia 14 Finland 17 France 19 Germany 20 Hungary 21 Iceland 23 Ireland 25 Israel 27 Italy 29 Kosovo 31 Lithuania 33 Netherlands 36 Norway 38 Poland 40 Portugal 43 Russian Federation 45 Slovakia 47 Slovenia 48 Spain 49 Sweden 52 Switzerland 53 Ukraine 56 United Kingdom 57 Albania 1. Political parties Language used in data file: Albanian Year of last election: 2009 Official party names, English 1. Partia Socialiste e Shqipërisë (PS) - The Socialist Party of Albania - 40,85 % names/translation, and size in last 2. Partia Demokratike e Shqipërisë (PD) - The Democratic Party of Albania - 40,18 % election: 3. Lëvizja Socialiste për Integrim (LSI) - The Socialist Movement for Integration - 4,85 % 4. Partia Republikane e Shqipërisë (PR) - The Republican Party of Albania - 2,11 % 5. Partia Socialdemokrate e Shqipërisë (PSD) - The Social Democratic Party of Albania - 1,76 % 6. Partia Drejtësi, Integrim dhe Unitet (PDIU) - The Party for Justice, Integration and Unity - 0,95 % 7. Partia Bashkimi për të Drejtat e Njeriut (PBDNJ) - The Unity for Human Rights Party - 1,19 % Description of political parties listed 1. The Socialist Party of Albania (Albanian: Partia Socialiste e Shqipërisë), is a social- above democratic political party in Albania; it is the leading opposition party in Albania. It seated 66 MPs in the 2009 Albanian parliament (out of a total of 140). It achieved power in 1997 after a political crisis and governmental realignment. In the 2001 General Election it secured 73 seats in the Parliament, which enabled it to form the Government.