Ournal J Concordia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Part-Time Faculty List 2019-2020 THEA M

Part-Time Faculty List 2019-2020 THEA M. ABRAHAM 2009 Director of Records Instructor of English B.A., Missouri Baptist University, 2003 M.S.E., Missouri Baptist University, 2007 M.A., University of Missouri-St. Louis, 2012 Graduate Certificate in Writing, University of Missouri-St. Louis, 2012 JUSTIN R. ARNETT 2018 Instructor of School of Nursing A.S., Mineral Area College, 2001 B.S.N., Central Methodist University, 2004 M.S.N., University of Missouri, 2007 JEANNE M. ARNOLD 2015 Instructor of School of Business B.S., Webster University, 1998 M.B.A., Webster University, 2006 DAVID AUBUCHON 2013 Instructor of School of Business A.A., Mineral Area College, 1999 B.S., Maryville University, 2001 M.B.A., Missouri Baptist University, 2011 NANCY M. BAKER 2018 Instructor of School of Education B.S., University of Missouri-St. Louis, 1981 M.Ed., National-Louis University, 1995 Ed.S., Missouri Baptist University, 2009 RUTH M. BANKS 2012 Instructor of School of Education B.A., Washington University, 1977 M.A., Washington University, 1981 M.A., University of Missouri-St. Louis, 1990 Ed.D., Saint Louis University, 1999 PAULA BERNHARDT 2019 Instructor of Fine Arts B.A.M., Lindenwood University, 2008 M.M., Webster University, 2010 MARILYN BERRY 2010 Instructor of School of Education B.S.E., Southwest Missouri State University, 1983 M.S., Southwest Baptist University, 2007 Additional Studies: Southwest Missouri State University, Lindenwood University RICK BIESIADECKI 2018 Instructor of Social and Behavioral Sciences B.S., Liberty University, 1992 M.Div., -

The Church's One Foundation

April 2011 Volume 38 Number 2 The Church’s One Foundation CURRENTS in Theology and Mission Currents in Theology and Mission Published by Lutheran School of Theology at Chicago in cooperation with Pacific Lutheran Theological Seminary Wartburg Theological Seminary Editors: Kathleen D. Billman, Kurt K. Hendel, Mark N. Swanson Lutheran School of Theology at Chicago [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Associate Editor: Craig L. Nessan Wartburg Theological Seminary (563-589-0207) [email protected] Assistant Editor: Ann Rezny [email protected] Copy Editor: Connie Sletto Editor of Preaching Helps: Craig A. Satterlee Lutheran School of Theology at Chicago [email protected] Editors of Book Reviews: Ralph W. Klein (Old Testament) Lutheran School of Theology at Chicago (773-256-0773) [email protected] Edgar M. Krentz (New Testament) Lutheran School of Theology at Chicago (773-256-0752) [email protected] Craig L. Nessan (history, theology, and ethics) Wartburg Theological Seminary (563-589-0207) [email protected] Circulation Office: 773-256-0751 [email protected] Editorial Board: Michael Aune (PLTS), James Erdman (WTS), Robert Kugler (PLTS), Jensen Seyenkulo (LSTC), Kristine Stache (WTS), Vítor Westhelle (LSTC). CURRENTS IN THEOLOGY AND MISSION (ISSN: 0098-2113) is published bimonthly (every other month), February, April, June, August, October, December. Annual subscription rate: $24.00 in the U.S.A., $28.00 elsewhere. Two-year rate: $44.00 in the U.S.A., $52.00 elsewhere. Three-year rate: $60.00 in the U.S.A., $72.00 elsewhere. Many back issues are available for $5.00, postage included. Published by Lutheran School of Theology at Chicago, a nonprofit organization, 1100 East 55th Street, Chicago, Illinois 60615, to which all business correspondence is to be addressed. -

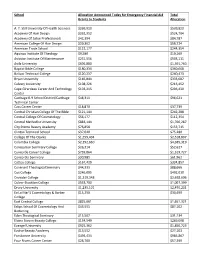

School Allocation Announced Today for Emergency Financial Aid Grants to Students Total Allocation A. T. Still University of Heal

School Allocation Announced Today for Emergency Financial Aid Total Grants to Students Allocation A. T. Still University Of Health Sciences $269,910 $539,820 Academy Of Hair Design $262,352 $524,704 Academy Of Salon Professionals $42,394 $84,787 American College Of Hair Design $29,362 $58,724 American Trade School $122,177 $244,354 Aquinas Institute Of Theology $9,580 $19,160 Aviation Institute Of Maintenance $251,556 $503,111 Avila University $695,880 $1,391,760 Baptist Bible College $180,334 $360,668 Bolivar Technical College $120,237 $240,473 Bryan University $166,844 $333,687 Calvary University $108,226 $216,452 Cape Girardeau Career And Technology $103,215 $206,430 Center Carthage R-9 School District/Carthage $48,311 $96,621 Technical Center Cass Career Center $18,870 $37,739 Central Christian College Of The Bible $121,144 $242,288 Central College Of Cosmetology $56,177 $112,354 Central Methodist University $883,144 $1,766,287 City Pointe Beauty Academy $76,858 $153,715 Clinton Technical School $37,640 $75,280 College Of The Ozarks $1,259,404 $2,518,807 Columbia College $2,192,660 $4,385,319 Conception Seminary College $26,314 $52,627 Concorde Career College $759,864 $1,519,727 Concordia Seminary $30,981 $61,962 Cottey College $167,429 $334,857 Covenant Theological Seminary $44,333 $88,666 Cox College $246,005 $492,010 Crowder College $1,319,348 $2,638,696 Culver-Stockton College $533,700 $1,067,399 Drury University $1,235,101 $2,470,201 Ea La Mar'S Cosmetology & Barber $15,250 $30,499 College East Central College $825,661 $1,651,321 -

The Sword, December 1974

Concordia College, St. Paul, Mn. Dec. 13, 1974 Vol. 10, No. 3 SALS accepts Seminex, 3 schools quit dialogue Concordia Seminary in Exile Forest and Bronxsville, N.Y., campus operations, The Role of (Seminex) of St. Louis, Missouri was sponsored the resolution. The SALS Women in the church, and the idea of granted membership into the organization consists of the various Academic Freedom for professors and Synodical Association of Lutheran Lutheran Church—Missouri Synod students. Out of a workshop defined Students Which met October 11-12 in affiliated schools in the United States to study the nature and purpose of Fort Wayne, Indiana, by a 7-3 margin. and Canada. Of the fifteen mem- SALS, the various delegates ex- Those school delegates which bership schools, ten were presented pressed the vital need to be a presented the resolution called for with more than fifty delegates. "resource organization" for the action which would provide "effective Seminex and the Lutheran Deaconess Lutheran schools and to encourage communication....For SALS, the Association were invited as guests to the conference hosts to create future rests upon how we effectively consider membership. SALS meets workshops dealing with religious, dialogue with each other." Also, they biannually to provide a com- social and academic life on campuses hoped that by taking such action, it munication between member schools today. Delegates expressed the would serve as "a positive step made leading to as exchange of ideas for concern that SALS is looking for for reconciliation, in the love and trust improving religious, social and "power to be recognized (by the of each other." By gaining mem- academic life; and to confront issues LCMS) but not recognized to be bership into the SALS organization, involving the schools of the Lutheran powerful" and directive in matters Seminex obtains voting privileges Church—Missouri Synod, (LCMS). -

Part‐Time Faculty 2021‐2022 THEA M. ABRAHAM 2009 Director of Records Instructor of English B.A

Part‐Time Faculty 2021‐2022 THEA M. ABRAHAM 2009 Director of Records Instructor of English B.A., Missouri Baptist University, 2003 M.S.E., Missouri Baptist University, 2007 M.A., University of Missouri‐St. Louis, 2012 Graduate Certificate in Writing, University of Missouri‐St. Louis, 2012 GREGORY ALMUS 2021 Instructor of School of Education B.S.B.A., University of Missouri‐Saint Louis, 1989 M.A., Lindenwood University, 1997 Ed.S., Lindenwood University, 2012 CYNTHIA A. ANDERS 2015 Instructor of Social & Behavioral Science B.S., Northwest Missouri State University, 1987 M.A., Lindenwood University, 2001 M.A.C., Missouri Baptist University, 2012 COREY J. ARBINI 2017 Instructor of School of Education B.A., Saint Louis University, 2000 M.A., Saint Louis University, 2005 Ed.S., Missouri Baptist University, 2012 Ed.D., Missouri Baptist University, 2016 NANCY M. BAKER 2018 Instructor of School of Education B.S., University of Missouri‐St. Louis, 1981 M.Ed., National‐Louis University, 1995 Ed.S., Missouri Baptist University, 2009 RUTH M. BANKS 2012 Instructor of School of Education B.A., Washington University, 1977 M.A., Washington University, 1981 M.A., University of Missouri‐St. Louis, 1990 Ed.D., Saint Louis University, 1999 Part‐Time Faculty 2021‐2022 1.28.21 LINDSAY BARTOE Instructor of School of Nursing 2018 B.S.N., Chamberlain University, 2009 M.S.N., Chamberlain University, 2013 QUEN BELL Instructor of Natural Sciences 2020 B.S., Logan College of Chiropractic, 2004 D.C., Logan College of Chiropractic, 2007 PAULA A. BENNETT 2000 Instructor of Fine Arts B.S., Louisiana State University, 1978 M.S., University of Southern Mississippi, 1977 ALAN G. -

Dr. Aaron Goldstein Assistant Professor of Old Testament Associate Director of Online Learning

C U R R I C U L U M V I T A E Dr. Aaron Goldstein Assistant Professor of Old Testament Associate Director of Online Learning Contact To reach me, please call or e-mail Gerry Reimer, Faculty Secretary, at 314.434.4044, ext. 4201 or [email protected]. Faculty Member Since 2015 Select Courses Taught Covenant Theology I (online) Hebrew I & II Old Testament Exegesis Online Student Orientation (online) Education Concordia Seminary, St. Louis, MO PhD in Biblical Studies (in progress, ABD) Covenant Theological Seminary, St. Louis, MO MDiv (Magna Cum Laude, 2010) – Elective emphasis in biblical studies Lindenwood University, St. Charles, MO BA (Magna Cum Laude, 2007) – Christian Ministry Studies major / Religion minor Ministry Experience Cornerstone Evangelical Free Church, St. Louis, MO Associate Pastor, 2014–2016 Assistant Pastor, 2008–2013 First Baptist Church of Ferguson, Ferguson, MO Student Minister, 2005–2007 COVENANT THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY 12330 CONWAY ROAD, ST. LOUIS, MO 6314 1 • WWW.COVENANTSEMINARY.EDU • 314.434.4044 Teaching Experience Covenant Theological Seminary, St. Louis, MO Assistant Professor of Old Testament, 2021–Present Associate Director of Online Learning, 2018–Present Adjunct Professor of Old Testament, 2018–2021 Interim Assistant Director of Online Learning, 2018 Visiting Instructor in Old Testament, 2015–2018 Teaching Assistant for Dr. Jay Sklar, Professor of Old Testament, 2009–2014 Lindenwood University, St. Charles, MO Adjunct Professor of Religion, 2014–2015 Concordia Seminary, St. Louis, MO Teaching Assistant, 2013–2014 Areas of Interest/Research New Testament Use of the Old Testament Old Testament Prophetical Books Gospels Biblical Languages Narrative Biblical Criticism Professional Societies and Memberships Evangelical Theological Society (2009–present) Society of Biblical Literature (2009–present) Publications and Paper Presentations ESV Men’s Devotional Bible. -

Opening Service 181St Academic Year

CONCORDIA SEMINARY, ST. LOUIS OPENING SERVICE 181ST ACADEMIC YEAR The Installations of Dr. Benjamin Haupt, Dr. Glenn Nielsen, Dr. David Peter, Dr. Mark Rockenbach and Dr. William Schumacher The Assignment of Vicarages and Internships The Tenth Week after Pentecost 10 a.m. Friday, August 23, 2019 The Chapel of St. Timothy and St. Titus Concordia Seminary, St. Louis In Nomine Jesu SERVICE OF THE WORD PRE-SERVICE MUSIC PROCESSIONAL HYMN Stand and face the processional cross, turning as it passes you. O Holy Spirit, Enter In (LSB 913) 913 O Holy Spirit, Enter In Public domain 1 SALUTATION AND PRAYER OF THE DAY L: The grace of our Lord ✠ Jesus Christ, the love of God and the communion of the Holy Spirit be with you all. C: And also with you. L: Let us pray … Father, Son and Holy Spirit. C: Amen. HYMN OF PRAISE O Splendor of God’s Glory Bright (LSB 874) 874 O Splendor of God's Glory Bright 5 On Christ, the true bread, let us feed; 5 On Christ,Let Him to us be drink indeed; the true bread, let us feed; 6 All laud to God the Father be; Let HimAnd let us taste with joyfulness to us be drink indeed; All praise, eternal Son, to Thee; And let usThe Holy Spirit’s plenteousness. taste with joyfulness All glory to the Spirit raise Alleluia! The Holy Spirit’s plenteousness. In equal and unending praise. 6 Alleluia!All laud to God the Father be; Alleluia! All praise, eternal Son, to Thee; All glory to the Spirit raise In equal and unending praise. -

The Word-Of-God Conflict in the Lutheran Church Missouri Synod in the 20Th Century

Luther Seminary Digital Commons @ Luther Seminary Master of Theology Theses Student Theses Spring 2018 The Word-of-God Conflict in the utherL an Church Missouri Synod in the 20th Century Donn Wilson Luther Seminary Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.luthersem.edu/mth_theses Part of the Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, and the History of Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Wilson, Donn, "The Word-of-God Conflict in the utherL an Church Missouri Synod in the 20th Century" (2018). Master of Theology Theses. 10. https://digitalcommons.luthersem.edu/mth_theses/10 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses at Digital Commons @ Luther Seminary. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Theology Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Luther Seminary. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. THE WORD-OF-GOD CONFLICT IN THE LUTHERAN CHURCH MISSOURI SYNOD IN THE 20TH CENTURY by DONN WILSON A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Luther Seminary In Partial Fulfillment, of The Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF THEOLOGY THESIS ADVISER: DR. MARY JANE HAEMIG ST. PAUL, MINNESOTA 2018 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Dr. Mary Jane Haemig has been very helpful in providing input on the writing of my thesis and posing critical questions. Several years ago, she guided my independent study of “Lutheran Orthodoxy 1580-1675,” which was my first introduction to this material. The two trips to Wittenberg over the January terms (2014 and 2016) and course on “Luther as Pastor” were very good introductions to Luther on-site. -

Linda Silman University of Missouri - St

OFFICE OF THE REGISTRAR PREPARED BY: LINDA SILMAN UNIVERSITY OF MISSOURI - ST. LOUIS AS OF CENSUS DATE: SEPT. 17, 2012 NEW TRANSFER STUDENTS ENROLLED FROM LAST COLLEGE ATTENDED FALL 2012 CBHE CHANGE CODE MISSOURI PUBLIC 4 YEAR INST 2011 2012 2011/2012 Concordia Seminary 0 1 1 Covenant Theological Seminary 0 1 1 2020 Harris-Stowe State College 25 20 (5) Hickey Business School 1 3 2 2030 Lincoln University 5 7 2 Missouri College 8 5 (3) 2040 Missouri Southern State University 4 3 (1) 2090 Missouri State University 51 54 3 1030 Missouri University of Science & Tech 13 16 3 2050 Missouri Western State Univeristy 1 3 2 2070 Northwest Missouri State University 4 7 3 Saint Mary's College Ofallon 0 1 1 Sanford-Brown Business College 8 7 (1) 2080 Southeast Missouri State University 32 25 (7) St. Louis Christian College 3 0 (3) 2060 Truman State University 20 25 5 2010 University of Central Missouri 17 19 2 1010 University of Missouri - Columbia 93 101 8 1020 University of Missouri - Kansas City 15 21 6 William Woods 1 0 (1) SOSUBTOTAL 301 319 18 FS12TRANSFERS CBHE CHANGE CODE MISSOURI PUBLIC TWO-YEAR INST 2011 2012 2011/2012 Blue River/Blue Springs Community College 0 1 1 Crowder College 1 1 0 3020 East Central College 23 13 (10) 3030 Jefferson College 70 84 14 Linn State Technical 0 1 1 3050 Longview Community College 1 4 3 Maple Woods Community College 2 0 (2) 3090 Mineral Area College 31 9 (22) 3100 Moberly 9 5 (4) North Central Missouri College 0 1 1 3025 Ozark Technical Communtiy College 5 3 (2) Penn Valley 5 0 (5) 3105 St. -

Concordia Seminary Magazine | Winter 2011

concordia s eminary WINTER 2011 A legacy of learning c oncordia s eminary FEATURES 4 Ministerial legacies: “God’s calling is specific to each individual” Although he represents a fifth generation to study for pastoral ministry, Micah Schmidt insists he is not entering a “family business.” And while other branches of the family also count pastors, teachers, and directors of Christian education, Schmidt adds that God did not call the family to be church workers. 8 Concordia Seminary Legacy Society This is the charter membership year for the recently launched Concordia Seminary Legacy Society. Members are those whose love for the proclamation of the Gospel of Jesus Christ includes remembering the mission of Concordia Seminary in their wills or estate plans. 10 History provides the lesson: Keep teaching Gerhard Bode is immersed in church history: He teaches historical theology at Concordia Seminary, where his office is lined with boxes of old materials and Cover Photograph photographs awaiting his attention as the Seminary archivist. C. F. W. Walther’s desk, from an exhibit at the Concordia 16 Commitment to community Historical Institute Eric, Linda, Hannah, Jonathan, Hailey, and Jocelyn Ekong have truly taken advantage by Emily Boedecker of the community-growth opportunities that the Seminary offers. “The community here is one that will take care of you when you are struggling and will rejoice with you during your joys,” Eric said. 23 From Call Day through the first year The Syth family of Gary, Keri, Ellie, and Peter was called to serve in Homer, Alaska, in 2009. Keri’s letter tells of their journey, from Seminary to their road trip across America to Alaskan adventures. -

Theological Seminary (Maine)

REGISTRATION COSTS DAY OF EXEGETICAL REFLECTION SCHEDULE Full registration ($130 per person, $140 after Sept. 6) Monday, September 19, 2011 includes program materials, Tuesday’s buffet reception, Werner Auditorium PAID 22ND ANNUAL and refreshments. Daily registration does not include Non-Profit Org. ST. LOUIS, MO U.S. POSTAGE The Bible in English: Its Present and Future Permit No. 1058 the Tuesday buffet. There is no registration fee for full- time students and faculty of CUS schools and the LCMS 8:00 a.m. Registration/check-in seminaries, though they must pre-register their attendance. 9:00 a.m. Welcome/Introductions Full-time students from other institutes can register at $30 9:10 a.m. Translation and Oral Performance per person. Meals can be purchased by all. 10:00 a.m. Break Registration deadline is Sept. 6. Please do not mail your 10:10 a.m. Beyond Equivalence: Translation Theory heological registration after this date. Fax, phone registration, or walk- Since Nida T ins only after Sept. 6. Walk-in registrations will not include 11:10 a.m. Chapel the Tuesday buffet reception, and the availability of meal 11:30 a.m. Lunch tickets cannot be guaranteed. 12:30 p.m. Translating the Psalms ymposiumAT CONCORDIA SEMINARY 1:30 p.m. Break S CANCELLATION POLICY 1:45 p.m. Translating Isaiah 40-55: Understanding the Instantaneous Perfect Verbs A full refund, less a $25 administration charge and less any 2:15 p.m. Natural Equivalence in Translation: meal tickets purchased, is made when a written or emailed cancellation is provided. No refund after Sept. -

Secondary Credit

Festus High School Human Services Career Cluster Suggested Individual Career and Academic Plan http://festus.k12.mo.us SUGGESTED COURSE OF HIGH SCHOOL STUDY Minimum Graduation Requirements It is suggested that students consider dual credit, articulation, or advanced placement opportunities for postsecondary credit. Required Courses/ Area Technical School of Jefferson Additional Learning Opportunities Grade English Math Science Social Studies Elective Options College School Based: Career Research Cooperative Education ELA I Algebra I Physical World History PEI Internship 9 or or Science Lifetime Health Job Shadowing Advanced ELA I Geometry/ Fine Arts Service Learning Project Advanced Geometry Foreign Language I Other: __________________________ Community Based: Mentorship Volunteer ELA II Geometry/ Biology US History PE II Part-time Employment 10 or Advanced Geometry Foreign Language II Other: Advanced ELA II or Public Speaking __________________________ Algebra II/ Advanced Algebra II Assessments/Certifications: Technical Skills Attainment (TSA) Other __________________________ Algebra II/ Early Childhood and Elementary Placement Assessment: ELA III Advanced Algebra II General US Government Personal Finance Secondary 11 or or Chem Foreign Language III Education I ACCUPLACER Advanced ELA III College Algebra Food Preparation ACT AP Statistics Nutrition Now PSAT General Psychology SAT ASVAB Other: __________________________ ELA IV College Algebra Anatomy and AP US History Child Development I Early Childhood and Elementary