The Dixiecrat Revolt and the End of the Solid South, 1932-1968'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Black History and the Class Struggle

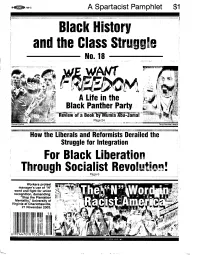

®~759.C A Spartacist Pamphlet $1 Black History i! and the Class Struggle No. 18 Page 24 ~iI~i~·:~:f!!iI'!lIiAI_!Ii!~1_&i 1·li:~'I!l~~.I_ :lIl1!tl!llti:'1!):~"1i:'S:':I'!mf\i,ri£~; : MINt mm:!~~!!)rI!t!!i\i!Ui\}_~ How the Liberals and Reformists Derailed the Struggle for Integration For Black Liberation Through Socialist Revolution! Page 6 VVorkers protest manager's use of "N" word and fight for union recognition, demanding: "Stop the Plantation Mentality," University of Virginia at Charlottesville, , 21 November 2003. I '0 ;, • ,:;. i"'l' \'~ ,1,';; !r.!1 I I -- - 2 Introduction Mumia Abu-Jamal is a fighter for the dom chronicles Mumia's political devel Cole's article on racism and anti-woman oppressed whose words teach powerful opment and years with the Black Panther bigotry, "For Free Abortion on Demand!" lessons and rouse opposition to the injus Party, as well as the Spartacist League's It was Democrat Clinton who put an "end tices of American capitalism. That's why active role in vying to win the best ele to welfare as we know it." the government seeks to silence him for ments of that generation from black Nearly 150 years since the Civil War ever with the barbaric death penaIty-a nationalism to revolutionary Marxism. crushed the slave system and won the legacy of slavery-,-Qr entombment for life One indication of the rollback of black franchise for black people, a whopping 13 for a crime he did not commit. The frame rights and the absence of militant black percent of black men were barred from up of Mumia Abu-Jamal represents the leadership is the ubiquitous use of the voting in the 2004 presidential election government's fear of the possibility of "N" word today. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses Third parties in twentieth century American politics Sumner, C. K. How to cite: Sumner, C. K. (1969) Third parties in twentieth century American politics, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/9989/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk "THIRD PARTIES IN TWENTIETH CENTURY AMERICAN POLITICS" THESIS PGR AS M. A. DEGREE PRESENTED EOT CK. SOMBER (ST.CUTHBERT«S) • JTJLT, 1969. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS. INTRODUCTION. PART 1 - THE PROGRESSIVE PARTIES. 1. THE "BOLL MOOSE" PROQRESSIVES. 2. THE CANDIDACY CP ROBERT M. L& FQLLETTE. * 3. THE PEOPLE'S PROGRESSIVE PARTI. PART 2 - THE SOCIALIST PARTY OF AMERICA* PART 3 * PARTIES OF LIMITED GEOGRAPHICAL APPEAL. -

COLORADO DEPARTMENT of STATE, Petitioner, V

No. 19-518 In the Supreme Court of the United States COLORADO DEPARTMENT OF STATE, Petitioner, v. MICHEAL BACA, POLLY BACA, AND ROBERT NEMANICH, Respondents. On Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit BRIEF OF AMICUS CURIAE COLORADO REPUBLICAN COMMITTEE IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONER JULIAN R. ELLIS, JR. Counsel of Record CHRISTOPHER O. MURRAY BROWNSTEIN HYATT FARBER SCHRECK, LLP 410 17th Street, Suite 2200 Denver, CO 80202 (303) 223-1100 [email protected] Attorneys for Amicus Curiae i QUESTIONS PRESENTED 1. Whether a presidential elector who is prevent- ed by their appointing State from casting an Elec- toral College ballot that violates state law lacks standing to sue their appointing State because they hold no constitutionally protected right to exercise discretion. 2. Does Article II or the Twelfth Amendment for- bid a State from requiring its presidential electors to follow the State’s popular vote when casting their Electoral College ballots. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page QUESTIONS PRESENTED ..................................... i TABLE OF CONTENTS .......................................... ii TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ................................... iii INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE ......................... 1 SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT ......................... 2 ARGUMENT .............................................................. 5 I. Political Parties’ Involvement in Selecting Nominees for Presidential Elector Is Constitutionally Sanctioned and Ubiquitous. ..... 5 A. States have plenary power over the appointment of presidential electors. ............ 5 B. Ray v. Blair expressly approved of pledges to political parties by candidates for presidential elector. ................................ 14 II. State Political Parties Must Be Allowed to Enforce Pledges to the Party by Candidates for Presidential Elector. ..................................... 17 CONCLUSION ......................................................... 22 iii TABLE OF AUTHORITIES Page(s) Cases Cal. -

Why Did the Democrats Lose the South? Bringing New Data to an Old Debate

Why did the Democrats Lose the South? Bringing New Data to an Old Debate Ilyana Kuziemko and Ebonya Washington∗ September 17, 2016 Abstract A long-standing debate in political economy is whether voters are driven primar- ily by economic self-interest or by less pecuniary motives such as ethnocentrism. Using newly available data, we reexamine one of the largest partisan shifts in a modern democ- racy: Southern whites' exodus from the Democratic Party, concentrated in the 1960s. Combining high-frequency survey data and textual newspaper analysis, we show that defection among racially conservative whites explains all (three-fourths) of the large decline in white Southern Democratic identification between 1958 and 1980 (2000). Racial attitudes also predict whites' partisan shifts earlier in the century. Relative to recent work, we find a much larger role for racial views and essentially no role for income growth or (non-race-related) policy preferences in explaining why Democrats \lost" the South. JEL codes: D72, H23, J15, N92 ∗We thank Frank Newport and Jeff Jones for answering our questions about the Gallup data. We are grateful to Alberto Alesina, Daron Acemoglu, Bill Collins, Marvin Danielson, Claudia Goldin, Matt Gentzkow, Alex Mas, Adrian Matray, Suresh Naidu, Jesse Shapiro, Seth Stephens-Davidowitz, Gavin Wright and seminar participants at the University of Chicago, Middlebury, NBER Summer Institute's Political Economy Workshop, the National Tax Association, NYU, Pomona, Princeton, Stanford SITE, University of Toronto, UBC, UCLA and Yale's CSAP Summer conference, par- ticularly discussants Georgia Kernell, Nolan McCarthy and Maya Sen for valuable comments and feedback. Khurram Ali, Jimmy Charit´e,Jos´ephineGantois, Keith Gladstone, Meredith Levine, Chitra Marti, Jenny Shen, Timothy Toh and Tammy Tseng provided truly exceptional research assistance. -

The Dixiecrat Movement of 1948: a Study in Political Conflict

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1972 The Dixiecrat Movement of 1948: A Study in Political Conflict Michael Terrence Lavin College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Political Science Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Lavin, Michael Terrence, "The Dixiecrat Movement of 1948: A Study in Political Conflict" (1972). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539624778. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-e3mx-tj71 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE DIXIECRAT MOVEMENT OF 1948 A STUDY IN POLITICAL CONFLICT A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Government The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Michael Terrence Lavin 1972 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Author Approved, May, 1972 Warner Moss 0 - Roger Sjnith V S t Jac^Edwards ii TABLE OP CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .......................... iv / LIST OF T A B L E S ..................................... v LIST OP FIGURES ............. Vii ABSTRACT .......... ' . viii INTRODUCTION . ..... 2 CHAPTER I. THE CHARACTERISTICS OP THE BLACK BELT REGIONS OF THE AMERICAN SOUTH ..... 9 CHAPTER II. THE CHARACTERISTICS OP THE DIXIECRAT MOVEMENT OP 19^8 .......... -

The Power of the Dixiecrats, Spring 1963

THE POWER OF--THE--Dl:X.IECRATS_,.--by-T-om·Hayden The last major stand of the Dixiecrats may be occurring in the 1963 hearings on the Kennedy civil rights bill • . Behind the wild accusations of communism in the civil rights movement and the trumpeted defense of prop~rty rights is a thinning legion of the Old Guard, How long will the Dixiecrat be such· a shrill and decisive force on the American political scene? The answer requir_es a review of Southern history, ideology, the policy of the New Frontier, and the international and national pres sures to do something about America's sore racial problem. The conclusion seems to be that the formal walls of segregation are being smashed, but the ~ite Man's Bur den can be carried in more subtle ways--as the people of the North we 11 knm-v, Dixiecrats in history For more th<m a generation the Demoo:pa,tie-~~-- -has - .been split ·deeply bet1r1een its Southern and Northern wings,. .the-former a safe bastion of racist conserV'atism and the latter a changing bloc of liberal reformers, The conflict is not new, and can- , _not be unde!'~~ood p~erly unless it is traced from the period of the :New Deal, In the 1936 election-the Democratic tide vJas rolling. Roosevelt brought to power 334 Democrats in the House against 89 Republicans. In the Senate 75 Democrats took seats against only 17 Republicans. The President's inaugural address promised the greatest liberal advances of this century: III see one-third of a nation ill-housed, ill-clad, ill-nouri9hed •••• It is not in despair that I paint you that picture. -

Download Download

134 Reviews Yet this does not mean that dependency theorists argue that conflict grows from a power imbalance. Barbieri concludes that instead of power imbalances result- ing in greater conflict between states, states with symmetric ties were in fact more likely to experience conflict. In the end, while Barbieri has made a signif- icant contribution to the field, she is willing to admit that while her findings are useful, questions still remain, and more research is needed to understand the exact nature of the interaction between trade and conflict. It is a noble admission from a scholar who has provided a spirited insight into this complex and impor- tant field. Z%e Liberal Illusion is not without its shortcomings, however. Although it is very dense, the book is, in fact, rather short, running to only 137 pages of text. There are sections in the book which provide some excellent analysis on how the Great Powers related to each other in terms of conflict and trade over the last century: The reader would appreciate more of this insight. Moreover, although it is brief, the book devotes considerable detail to explaining the nuances of Barbieri's methodology. While important, readers would likely have traded the extensive equations for more examples that actually address real world relation- ships and conflict. As a result, the books reads like a dissertation (it was), which, while brilliant, could have been expanded and refined somewhat. It also might be appreciated more by political theorists than historians, who will find the rig- orous methodology and extensive data somewhat removed from historical events. -

Why Did the Democrats Lose the South? Bringing New Data to an Old Debate

Why did the Democrats Lose the South? Bringing New Data to an Old Debate Ilyana Kuziemko and Ebonya Washington∗ September 17, 2016 Abstract A long-standing debate in political economy is whether voters are driven primar- ily by economic self-interest or by less pecuniary motives such as ethnocentrism. Using newly available data, we reexamine one of the largest partisan shifts in a modern democ- racy: Southern whites' exodus from the Democratic Party, concentrated in the 1960s. Combining high-frequency survey data and textual newspaper analysis, we show that defection among racially conservative whites explains all (three-fourths) of the large decline in white Southern Democratic identification between 1958 and 1980 (2000). Racial attitudes also predict whites' partisan shifts earlier in the century. Relative to recent work, we find a much larger role for racial views and essentially no role for income growth or (non-race-related) policy preferences in explaining why Democrats \lost" the South. JEL codes: D72, H23, J15, N92 ∗We thank Frank Newport and Jeff Jones for answering our questions about the Gallup data. We are grateful to Alberto Alesina, Daron Acemoglu, Bill Collins, Marvin Danielson, Claudia Goldin, Matt Gentzkow, Alex Mas, Adrian Matray, Suresh Naidu, Jesse Shapiro, Seth Stephens-Davidowitz, Gavin Wright and seminar participants at the University of Chicago, Middlebury, NBER Summer Institute's Political Economy Workshop, the National Tax Association, NYU, Pomona, Princeton, Stanford SITE, University of Toronto, UBC, UCLA and Yale's CSAP Summer conference, par- ticularly discussants Georgia Kernell, Nolan McCarthy and Maya Sen for valuable comments and feedback. Khurram Ali, Jimmy Charit´e,Jos´ephineGantois, Keith Gladstone, Meredith Levine, Chitra Marti, Jenny Shen, Timothy Toh and Tammy Tseng provided truly exceptional research assistance. -

Governance Studies

Issues in Governance Studies Number 61 September 2013 This Too Shall Pass: Reflections on the Repositioning of Political Parties Pietro S. Nivola INTRODUCTION mid the perennial lament about partisan “gridlock” and “dysfunction” in Washington, a casual observer might conclude that the postures of the ADemocrats and Republicans are permanent fixtures. Year in and year out, the two sides, it is easy to infer, look hopelessly set in their ways. But the inference is shortsighted. Repeatedly in American history, the leading political parties have changed their policy positions, sometimes startlingly. Consider these examples. Pietro Nivola is a senior fellow emeritus and served For a time, during the earliest years of the republic, the so-called Republicans as VP and director of Governance Studies (not to be confused with today’s party bearing the same name) resisted from 2004-2008. He practically every facet of the Federalist agenda, which featured a larger role for has written widely on energy policy, a central government as advocated by Alexander Hamilton. By 1815, however, regulation, federalism the Republican Party had pivoted. Led by James Madison, it suddenly embraced and American politics. just about every one of Hamilton’s main prescriptions. Born in 1854, another Republican party—the one built by Lincoln—became the champion of greater racial equality. It continued to enjoy that reputation well into the 20th century. (A little known fact: As late as 1932, black voters were still casting the great majority of their ballots for the Republican presidential candidate.) On the race issue, the Democrats were the reactionary party. That shameful distinction began to fade in the course of the 1930s and 1940s. -

First Two-Party System Federalists V. Democratic-Republicans, 1780S - 1801

First Two-Party System Federalists v. Democratic-Republicans, 1780s - 1801 Federalists Republicans 1. Favored strong central government 1. Emphasized states' rights 2. "Loose" interpretation of the 2. "Strict" interpretation of the Constitution Constitution 3. Encouragement of manufacturing 3. Preference for agriculture and rural life 4. Strongest in Northeast 4. Strength in South and West 5. Favored close ties with Britain. 5. Favored ties with France over Britain Second Two-Party System Democrats v. Whigs, 1836 - 1850 Liberty and Free Soil were small independent parties during this time period. Democrats Whigs 1. The party of tradition 1. The party of modernization 2. Looked backward to the past. 2. Looked forward to the future. 3. Spoke to the fears of Americans 3. Spoke to the hopes of Americans 4. Opposed state-legislated reforms and 4. Wanted to use federal government to preferred individual freedom of choice. promote economic growth 5. Favored farms and rural independence 5. favored industry and urban growth and and the right to own slaves. paying workers 6. Favored rapid territorial expansion, 6. Favored gradual territorial expansion even if it meant war with Mexico and opposed war with Mexico . Republican Party begins 1. Formed in 1854 when a coalition of Independent Democrats, Free Soilers, and Conscience Whigs united in opposition to the Kansas-Nebraska Bill. The Republican Era 1. From 1921 to 1933 both the presidency and congress were dominated by Republicans (Presidents Harding, Coolidge, and Hoover). The Democrat Era 1. Created a Democratic party coalition that would dominate American politics for many years (1933-1952). (Presidents Roosevelt and Truman) Dixiecrat Party of 1948: Southern conservative Democrats known as "Dixiecrats." Opposed the civil rights plank in the Democratic platform. -

University Microfilms

INFORMATION TO USERS This dissertation was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in ' sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections w ith a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

Dixiecrat Bolt Parbacks

WEDNESDAY, JUNE 25, 1952 Avenge Daily Net Press Run Th* Weather ^AGE TWENTY-FOTJE T o r tha WMk BadMl VerMoot of tf. 8 . Weetlwr 1 . IfflautljfHtfr Httiftting !ijgralb JnH. Zl,*1982 HM th J. ovotHmg, Edmonds,-- Raymond Gorsky, Uiundar shewora PrMajr.' * King David lodge. No. 81, Elaine Hlncka, Barbara Hughes, 10^593 lOOF. wU» meet this Friday eve Reveals RHS Elaine Jackson, Robert Kingsbury, Fridoy nlgSt. Mlaimum . 1 Joan Lee,Moyce Lugiribuhl, Elaine BAND MMilwr of tbs AoSK - T fT ?i About Town ning at 7:30 in Odd Fellows Hall. Pickral'Mostoni Wedding Bunsui ot CZreulAtloii. A district meeting will be held Masker, Virginia Metcalf, William ‘ SALVATION ARMY BAND M anchester^ A City of Village Charm I Th« daughter, bom Monday In for Districts 24 and 30. The grand Top Students Miller, Muriel Murphy. Rochelle the Mancheeter-Memorial Hoapltal master and the district deputy Shlrokl, • Beverly Ward, Dorothy Weekes. Eleanor Welz and Mary to Mr. and Mm. Charles Robinson gr and master will be present. The (ClRMifled AdverUsbig on Png. 18J tfMM been named'Carla Marion. iniMatory degree team \vill por Fourth Quarter’s Honor Wilhelm. "Friday, June 27 - 8 P. M. VOL. LXXI, NO. 228 MANCHESTER, CONN., THURSDAY. JUNE 26.1952 (TWENTY PAGES) -PRICE PIVS tray the initiatory degree tomor Roll Is Announced by Freshmen winning high honors UNITED METHODIST CHURCH A daughter was bom this Sun row night- at the Kim lodge in were: Carol Bakulakl, Richard AT QUABRYVILLE IN BOLTON day to Mr. and Mrs. William John Glastonbury. Principal A. L. Dresser Blesladecki. Francis Carter, Jo ston of 183 Lydall street at the seph Cacello, Harry Cohen, Ralph f o o d h a l e APRON SALE .