The Response of the Black Community in Mississippi to The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

William F. Winter and the Politics of Racial Moderation in Mississippi

WILLIAM WINTER AND THE POLITICS OF RACIAL MODERATION 335 William F. Winter and the Politics of Racial Moderation in Mississippi by Charles C. Bolton On May 12, 2008, William F. Winter received the Profile in Courage Award from the John F. Kennedy Foundation, which honored the former Mississippi governor for “championing public education and racial equality.” The award was certainly well deserved and highlighted two important legacies of one of Mississippi’s most important public servants in the post–World War II era. During Senator Edward M. Kennedy’s presentation of the award, he noted that Winter had been criticized “for his integrationist stances” that led to his defeat in the gubernatorial campaign of 1967. Although Winter’s opponents that year certainly tried to paint him as a moderate (or worse yet, a liberal) and as less than a true believer in racial segregation, he would be the first to admit that he did not advocate racial integration in 1967; indeed, much to his regret later, Winter actually pandered to white segregationists in a vain attempt to win the election. Because Winter, over the course of his long career, has increasingly become identified as a champion of racial justice, it is easy, as Senator Kennedy’s remarks illustrate, to flatten the complexity of Winter’s evolution on the issue CHARLES C. BOLTON is the guest editor of this special edition of the Journal of Mississippi History focusing on the career of William F. Winter. He is profes- sor and head of the history department at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. -

1 Rosedale's Beginnings and Municipal Development

1 Rosedale's Beginnings and Municipal Development EVELYN LOWRY Beginnings For hundreds of years prior to 1876, the area of Bolivar County in which Rosedale is located had been traversed by countless numbers of explorers and Indians. A heavily forested region in the early nineteenth century, it abounded in a variety of wildlife. Indeed, as late as the mid-nineteenth century the western part of Bolivar County was very much the "forest primeval." Due to the importance of the Mississippi River, in time numerous boat landings sprang up along its banks to accommodate those who plied the "father of waters." Among these was Abel's Point, - just below the present-day Rosedale Cemetery. Moreover, in the 1850's settlement activity intensified in this vicinity. Among those who moved into this area was Colonel Lafayette Jones, who arrived in 1855. Settling down and building a home, Jones named his residence "Rosedale," after his family estate in Virginia. Thus, a seed was planted. Eventually, as a result of the River's capriciousness, Abel's Landing was moved downriver. In time, Prentiss Landing developed, Evelyn Lowry received her B.S.E. and M.Ed. degrees from Delta State University in Cleveland, Mississippi. Currently she is a doctoral candidate in history at Memphis State University. 2 HISTORY OF ROSEDALE, MISSISSIPPI but it was burned in 1862 during the hostilities of the Civil War. This particular location was now generally referred to as Lower Rosedale. However, during the aftermath of the Civil War known as "recon- struction," the area came to be known as Floreyville, named for a reconstructionist who lived there. -

Preface Chapter 1

Notes Preface 1. Alfred Pearce Dennis, “Humanizing the Department of Commerce,” Saturday Evening Post, June 6, 1925, 8. 2. Herbert Hoover, Memoirs: The Cabinet and the Presidency, 1920–1930 (New York: Macmillan, 1952), 184. 3. Herbert Hoover, “The Larger Purposes of the Department of Commerce,” in “Republi- can National Committee, Brief Review of Activities and Policies of the Federal Executive Departments,” Bulletin No. 6, 1928, Herbert Hoover Papers, Campaign and Transition Period, Box 6, “Subject: Republican National Committee,” Hoover Presidential Library, West Branch, Iowa. 4. Herbert Hoover, “Responsibility of America for World Peace,” address before national con- vention of National League of Women Voters, Des Moines, Iowa, April 11, 1923, Bible no. 303, Hoover Presidential Library. 5. Bruce Bliven, “Hoover—And the Rest,” Independent, May 29, 1920, 275. Chapter 1 1. John W. Hallowell to Arthur (Hallowell?), November 21, 1918, Hoover Papers, Pre-Com- merce Period, Hoover Presidential Library, West Branch, Iowa, Box 6, “Hallowell, John W., 1917–1920”; Julius Barnes to Gertrude Barnes, November 27 and December 5, 1918, ibid., Box 2, “Barnes, Julius H., Nov. 27, 1918–Jan. 17, 1919”; Lewis Strauss, “Further Notes for Mr. Irwin,” ca. February 1928, Subject File, Lewis L. Strauss Papers, Hoover Presidential Library, West Branch, Iowa, Box 10, “Campaign of 1928: Campaign Literature, Speeches, etc., Press Releases, Speeches, etc., 1928 Feb.–Nov.”; Strauss, handwritten notes, December 1, 1918, ibid., Box 76, “Strauss, Lewis L., Diaries, 1917–19.” 2. The men who sailed with Hoover to Europe on the Olympic on November 18, 1918, were Julius Barnes, Frederick Chatfi eld, John Hallowell, Lewis Strauss, Robert Taft, and Alonzo Taylor. -

Candidates Prepare for Final Showdown

Matawan holds onto lead in Register Top Ten, 1B MONMOUTH COUNTY'S HOMETOWN NEWSPAPER SINCE 1878 ister )AY. NOV 8. 1988 VOL. 111 NO. .13 25 i Lawyer: Hunt Meet Candidates prepare not legal for final showdown By VIRGINIA KEMTDORRI8 bid to topple incumbent U.S. Sen. Frank Lautenberg. THE REGISTER BySEAMUSMcORAW The latest Eagleton poll, however, gives Lautenberg a THE REGISTER solid 12-point lead over the one-time Heisman Tro- phy winner and Rhodes scholar. MIDDLETOWN — The state On the congressional level, the race to fill How- Attorney General's Office will Politicians and campaign workers spent much of ard's seat — in which Libertarian Laura Stewart it look into whether the annual Hunt yesterday in a last-minute push before today's general also a candidate — has drawn national attention, in Race Meet operates legally be- election. pan because it is one of the few seats nationwide with cause of inquiries made by local "We've been out all weekend," said Wendy Do- no incumbent. attorney Larry S. Loigman. nath, a spokesman for 3rd Congressional District The picture is further complicated by the fact that Loigman, who has vowed to hopeful Joseph Azzolina. with Howard's death and the resignation of Demo- "make sure that this year's hunt is Azzolina is hoping to top Democratic state Sen. cratic Rep. Peter Rodino of Newark, the state's pres- the last one," last month contacted Frank Pallone in the race to fill the seat left vacant by tige level in Congress is reported to be on the decline. -

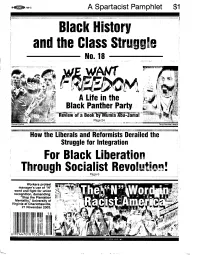

Black History and the Class Struggle

®~759.C A Spartacist Pamphlet $1 Black History i! and the Class Struggle No. 18 Page 24 ~iI~i~·:~:f!!iI'!lIiAI_!Ii!~1_&i 1·li:~'I!l~~.I_ :lIl1!tl!llti:'1!):~"1i:'S:':I'!mf\i,ri£~; : MINt mm:!~~!!)rI!t!!i\i!Ui\}_~ How the Liberals and Reformists Derailed the Struggle for Integration For Black Liberation Through Socialist Revolution! Page 6 VVorkers protest manager's use of "N" word and fight for union recognition, demanding: "Stop the Plantation Mentality," University of Virginia at Charlottesville, , 21 November 2003. I '0 ;, • ,:;. i"'l' \'~ ,1,';; !r.!1 I I -- - 2 Introduction Mumia Abu-Jamal is a fighter for the dom chronicles Mumia's political devel Cole's article on racism and anti-woman oppressed whose words teach powerful opment and years with the Black Panther bigotry, "For Free Abortion on Demand!" lessons and rouse opposition to the injus Party, as well as the Spartacist League's It was Democrat Clinton who put an "end tices of American capitalism. That's why active role in vying to win the best ele to welfare as we know it." the government seeks to silence him for ments of that generation from black Nearly 150 years since the Civil War ever with the barbaric death penaIty-a nationalism to revolutionary Marxism. crushed the slave system and won the legacy of slavery-,-Qr entombment for life One indication of the rollback of black franchise for black people, a whopping 13 for a crime he did not commit. The frame rights and the absence of militant black percent of black men were barred from up of Mumia Abu-Jamal represents the leadership is the ubiquitous use of the voting in the 2004 presidential election government's fear of the possibility of "N" word today. -

INTERSPECIES SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT: Intersectional Empathetic Approaches to Food and Climate Justice

1 INTERSPECIES SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT: intersectional empathetic approaches to food and climate justice A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Policy and Governance at the University of Canterbury Éilis Rose Espiner i “He aroha whakatō, he aroha puta mai” (where kindness is sown, kindness will be received) ii Table of Contents Abstract .............................................................................................................................................. iv Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................................. v Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 0 What is Sustainable Development? .................................................................................................... 1 Literature Review ................................................................................................................................ 2 Theory ................................................................................................................................................. 7 Chapter one: environmental impacts of current food system ............................................................. 11 Inefficient consumption patterns ..................................................................................................... 11 Resource-intensive ........................................................................................................................... -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses Third parties in twentieth century American politics Sumner, C. K. How to cite: Sumner, C. K. (1969) Third parties in twentieth century American politics, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/9989/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk "THIRD PARTIES IN TWENTIETH CENTURY AMERICAN POLITICS" THESIS PGR AS M. A. DEGREE PRESENTED EOT CK. SOMBER (ST.CUTHBERT«S) • JTJLT, 1969. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS. INTRODUCTION. PART 1 - THE PROGRESSIVE PARTIES. 1. THE "BOLL MOOSE" PROQRESSIVES. 2. THE CANDIDACY CP ROBERT M. L& FQLLETTE. * 3. THE PEOPLE'S PROGRESSIVE PARTI. PART 2 - THE SOCIALIST PARTY OF AMERICA* PART 3 * PARTIES OF LIMITED GEOGRAPHICAL APPEAL. -

![Biographical Data of Members of Senate and House, Personnel of Standing Committees [1968] Mississippi](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2560/biographical-data-of-members-of-senate-and-house-personnel-of-standing-committees-1968-mississippi-1082560.webp)

Biographical Data of Members of Senate and House, Personnel of Standing Committees [1968] Mississippi

University of Mississippi eGrove Mississippi Legislature Hand Books State of Mississippi Government Documents 1968 Hand book : biographical data of members of Senate and House, personnel of standing committees [1968] Mississippi. Legislature Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/sta_leghb Part of the American Politics Commons Recommended Citation Mississippi. Legislature, "Hand book : biographical data of members of Senate and House, personnel of standing committees [1968]" (1968). Mississippi Legislature Hand Books. 12. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/sta_leghb/12 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the State of Mississippi Government Documents at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mississippi Legislature Hand Books by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ST.DOC. 1 6 7 SENATETELEPHONE DIRECTORY Lieutenant Governor -------------------------------- 354-6788 Senators :------------------------- _______________354-6790 Appropriations Committee1ttee -------------------------------------- 354-6365 CalendarCleark _:::::::::::~-=:::~~::::::::::::::=:=:::::=-~~~;!~! £ting Office ___ _ __________ _ -------------------------------- 354-7128 FINANCEo --------------------------------------- 354-6761 Journal Clerk & Bookkeeper _________354-6790 or 948-5148 Judiciary Committee ____ _______________________________________ 354-6017 Mag Card Operators _______________________________________354-6846 Medical Unit -------------------------------------------------- -

COLORADO DEPARTMENT of STATE, Petitioner, V

No. 19-518 In the Supreme Court of the United States COLORADO DEPARTMENT OF STATE, Petitioner, v. MICHEAL BACA, POLLY BACA, AND ROBERT NEMANICH, Respondents. On Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit BRIEF OF AMICUS CURIAE COLORADO REPUBLICAN COMMITTEE IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONER JULIAN R. ELLIS, JR. Counsel of Record CHRISTOPHER O. MURRAY BROWNSTEIN HYATT FARBER SCHRECK, LLP 410 17th Street, Suite 2200 Denver, CO 80202 (303) 223-1100 [email protected] Attorneys for Amicus Curiae i QUESTIONS PRESENTED 1. Whether a presidential elector who is prevent- ed by their appointing State from casting an Elec- toral College ballot that violates state law lacks standing to sue their appointing State because they hold no constitutionally protected right to exercise discretion. 2. Does Article II or the Twelfth Amendment for- bid a State from requiring its presidential electors to follow the State’s popular vote when casting their Electoral College ballots. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page QUESTIONS PRESENTED ..................................... i TABLE OF CONTENTS .......................................... ii TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ................................... iii INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE ......................... 1 SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT ......................... 2 ARGUMENT .............................................................. 5 I. Political Parties’ Involvement in Selecting Nominees for Presidential Elector Is Constitutionally Sanctioned and Ubiquitous. ..... 5 A. States have plenary power over the appointment of presidential electors. ............ 5 B. Ray v. Blair expressly approved of pledges to political parties by candidates for presidential elector. ................................ 14 II. State Political Parties Must Be Allowed to Enforce Pledges to the Party by Candidates for Presidential Elector. ..................................... 17 CONCLUSION ......................................................... 22 iii TABLE OF AUTHORITIES Page(s) Cases Cal. -

1969 NGA Annual Meeting

Proceedings OF THE NATIONAL GOVERNORS' CONFERENCE 1969 SIXTY-FIRST ANNUAL MEETING BROADMOOR HOTEL • COLORADO SPRINGS, COLORADO AUGUST 31-SEPTEMBER 3, 1969 THE NATIONAL GOVERNORS' CONFERENCE IRON WORKS PIKE LEXINGTON, KENTUCKY 40505 THE COUNCil OF S1'ATE GOVERNMENTS IRON WORKS PIKE LEXINGTON, KENTUCKY 40511 J Published by THE NATIONAL GOVERNORS' CONFERENCE IRON WORKS PIKE LEXINGTON, KENTUCKY 40505 CONTENTS Executive Committee Rosters v Other Committees of the Conference vi Governors and Guests in Attendance viii Program of the Annual Meeting xi Monday Sessions-September 1 Welcoming Remarks-Governor John A. Love 1 Address of the Chairman-Governor Buford Ellington 2 Adoption of Rules of Procedure . 4 Remarks of Monsieur Pierre Dumont 5 "Governors and the Problems of the Cities" (including reports and policy statements of the Committee on Community Development and Urban Relations), Governor Richard J. Hughes presiding .. 6 Remarks of Secretary George Romney . .. 15 "Revenue Sharing" (including reports and policy statements of the Committee on Executive Management and Fiscal Affairs), Governor Daniel J. Evans presiding . 33 Remarks of Dr. Arthur F. Burns .. 36 Remarks of Vice-President Spiro T. Agnew 43 State Ball Remarks of Governor John A. Love 57 Remarks of Governor Buford Ellington 57 Address by the President of the United States 58 Tuesday Sessions-September 2 "Major Issues in Human Resources" (including reports and policy statements of the Committee on Human Resources), Governor Nelson A. Rockefeller presiding . 68 Remarks of Secretary George P. Shultz 87 "Transportation" (including reports and policy statements of the Committee on Transportation, Commerce, and Technology), Governor John A. Love presiding 95 Remarks of Secretary John A. -

Why Did the Democrats Lose the South? Bringing New Data to an Old Debate

Why did the Democrats Lose the South? Bringing New Data to an Old Debate Ilyana Kuziemko and Ebonya Washington∗ September 17, 2016 Abstract A long-standing debate in political economy is whether voters are driven primar- ily by economic self-interest or by less pecuniary motives such as ethnocentrism. Using newly available data, we reexamine one of the largest partisan shifts in a modern democ- racy: Southern whites' exodus from the Democratic Party, concentrated in the 1960s. Combining high-frequency survey data and textual newspaper analysis, we show that defection among racially conservative whites explains all (three-fourths) of the large decline in white Southern Democratic identification between 1958 and 1980 (2000). Racial attitudes also predict whites' partisan shifts earlier in the century. Relative to recent work, we find a much larger role for racial views and essentially no role for income growth or (non-race-related) policy preferences in explaining why Democrats \lost" the South. JEL codes: D72, H23, J15, N92 ∗We thank Frank Newport and Jeff Jones for answering our questions about the Gallup data. We are grateful to Alberto Alesina, Daron Acemoglu, Bill Collins, Marvin Danielson, Claudia Goldin, Matt Gentzkow, Alex Mas, Adrian Matray, Suresh Naidu, Jesse Shapiro, Seth Stephens-Davidowitz, Gavin Wright and seminar participants at the University of Chicago, Middlebury, NBER Summer Institute's Political Economy Workshop, the National Tax Association, NYU, Pomona, Princeton, Stanford SITE, University of Toronto, UBC, UCLA and Yale's CSAP Summer conference, par- ticularly discussants Georgia Kernell, Nolan McCarthy and Maya Sen for valuable comments and feedback. Khurram Ali, Jimmy Charit´e,Jos´ephineGantois, Keith Gladstone, Meredith Levine, Chitra Marti, Jenny Shen, Timothy Toh and Tammy Tseng provided truly exceptional research assistance. -

Isaiah T. Montgomery and the Mississippi Constitution: STRATEGY UNDER EXTREME ADVERSITY (Revised to December 12 2016 ) (Copyright, 2016

Isaiah T. Montgomery and the Mississippi Constitution: STRATEGY UNDER EXTREME ADVERSITY (Revised to December 12 2016 ) (Copyright, 2016. Matthew Holden Jr. EDIT FOR GLITCHES Isaiah T. Montgomery and the Mississippi Constitution: Strategy under Extreme Adversity Matthew Holden, Jr. President, Isaiah T. Montgomery Studies Project. [email protected]( .) Retired Wepner Distinguished Professor in Political Science, University of Illinois at Springfield; Professor Emeritus of Politics, University of Virginia. Introduction This paper is an outgrowth from the notes used in a roundtable on March 19, 2016. The roundtable was proposed to the National Conference of Black Political Scientists (NCOBPS), and approved for its 2016 meeting in Jackson, Mississippi. The roundtable was held in the House of Representatives Chamber in the Old Capitol Museum, and was 1 open without charge to any member of the public. 1. Todd C. Shaw, 2016 President of National Conference of Black Politica Scientist s (NCOBPS), and Sekou Franklin, 2016 Program Co-Chair, encouraged and assisted in the scheduling of the roundtable. Katherine Blount (Director, Mississippi Department of Archives and History), Connie Michael (Facilities Use Coordinator, The Old Capitol Museum, and Trey Roberts (Mississippi Department of Archives and History) assisted in getting the use of the chamber and in presenting information on the Mississippi 2Museums project. The cost of the chamber was paid by Matthew Holden, Jr, from private income in behalf of the Isaiah T. Montgomery Studies Project. The chair of the round table was Michael V. Williams, Dean of the Social Science Division Tougaloo College. The other participants were Dorothy Pratt (University of South Carolina).Jeanne Middleton-Hairston (Millsaps College), Byron D’Andra Orey (Jackson State University), and Dr.