The Power of the Dixiecrats, Spring 1963

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A History of Maryland's Electoral College Meetings 1789-2016

A History of Maryland’s Electoral College Meetings 1789-2016 A History of Maryland’s Electoral College Meetings 1789-2016 Published by: Maryland State Board of Elections Linda H. Lamone, Administrator Project Coordinator: Jared DeMarinis, Director Division of Candidacy and Campaign Finance Published: October 2016 Table of Contents Preface 5 The Electoral College – Introduction 7 Meeting of February 4, 1789 19 Meeting of December 5, 1792 22 Meeting of December 7, 1796 24 Meeting of December 3, 1800 27 Meeting of December 5, 1804 30 Meeting of December 7, 1808 31 Meeting of December 2, 1812 33 Meeting of December 4, 1816 35 Meeting of December 6, 1820 36 Meeting of December 1, 1824 39 Meeting of December 3, 1828 41 Meeting of December 5, 1832 43 Meeting of December 7, 1836 46 Meeting of December 2, 1840 49 Meeting of December 4, 1844 52 Meeting of December 6, 1848 53 Meeting of December 1, 1852 55 Meeting of December 3, 1856 57 Meeting of December 5, 1860 60 Meeting of December 7, 1864 62 Meeting of December 2, 1868 65 Meeting of December 4, 1872 66 Meeting of December 6, 1876 68 Meeting of December 1, 1880 70 Meeting of December 3, 1884 71 Page | 2 Meeting of January 14, 1889 74 Meeting of January 9, 1893 75 Meeting of January 11, 1897 77 Meeting of January 14, 1901 79 Meeting of January 9, 1905 80 Meeting of January 11, 1909 83 Meeting of January 13, 1913 85 Meeting of January 8, 1917 87 Meeting of January 10, 1921 88 Meeting of January 12, 1925 90 Meeting of January 2, 1929 91 Meeting of January 4, 1933 93 Meeting of December 14, 1936 -

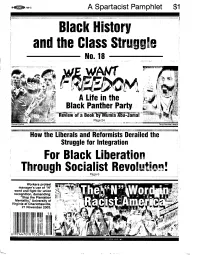

Black History and the Class Struggle

®~759.C A Spartacist Pamphlet $1 Black History i! and the Class Struggle No. 18 Page 24 ~iI~i~·:~:f!!iI'!lIiAI_!Ii!~1_&i 1·li:~'I!l~~.I_ :lIl1!tl!llti:'1!):~"1i:'S:':I'!mf\i,ri£~; : MINt mm:!~~!!)rI!t!!i\i!Ui\}_~ How the Liberals and Reformists Derailed the Struggle for Integration For Black Liberation Through Socialist Revolution! Page 6 VVorkers protest manager's use of "N" word and fight for union recognition, demanding: "Stop the Plantation Mentality," University of Virginia at Charlottesville, , 21 November 2003. I '0 ;, • ,:;. i"'l' \'~ ,1,';; !r.!1 I I -- - 2 Introduction Mumia Abu-Jamal is a fighter for the dom chronicles Mumia's political devel Cole's article on racism and anti-woman oppressed whose words teach powerful opment and years with the Black Panther bigotry, "For Free Abortion on Demand!" lessons and rouse opposition to the injus Party, as well as the Spartacist League's It was Democrat Clinton who put an "end tices of American capitalism. That's why active role in vying to win the best ele to welfare as we know it." the government seeks to silence him for ments of that generation from black Nearly 150 years since the Civil War ever with the barbaric death penaIty-a nationalism to revolutionary Marxism. crushed the slave system and won the legacy of slavery-,-Qr entombment for life One indication of the rollback of black franchise for black people, a whopping 13 for a crime he did not commit. The frame rights and the absence of militant black percent of black men were barred from up of Mumia Abu-Jamal represents the leadership is the ubiquitous use of the voting in the 2004 presidential election government's fear of the possibility of "N" word today. -

A History of the Virginia Democratic Party, 1965-2015

A History of the Virginia Democratic Party, 1965-2015 A Senior Honors Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation “with Honors Distinction in History” in the undergraduate colleges at The Ohio State University by Margaret Echols The Ohio State University May 2015 Project Advisor: Professor David L. Stebenne, Department of History 2 3 Table of Contents I. Introduction II. Mills Godwin, Linwood Holton, and the Rise of Two-Party Competition, 1965-1981 III. Democratic Resurgence in the Reagan Era, 1981-1993 IV. A Return to the Right, 1993-2001 V. Warner, Kaine, Bipartisanship, and Progressive Politics, 2001-2015 VI. Conclusions 4 I. Introduction Of all the American states, Virginia can lay claim to the most thorough control by an oligarchy. Political power has been closely held by a small group of leaders who, themselves and their predecessors, have subverted democratic institutions and deprived most Virginians of a voice in their government. The Commonwealth possesses the characteristics more akin to those of England at about the time of the Reform Bill of 1832 than to those of any other state of the present-day South. It is a political museum piece. Yet the little oligarchy that rules Virginia demonstrates a sense of honor, an aversion to open venality, a degree of sensitivity to public opinion, a concern for efficiency in administration, and, so long as it does not cost much, a feeling of social responsibility. - Southern Politics in State and Nation, V. O. Key, Jr., 19491 Thus did V. O. Key, Jr. so famously describe Virginia’s political landscape in 1949 in his revolutionary book Southern Politics in State and Nation. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses Third parties in twentieth century American politics Sumner, C. K. How to cite: Sumner, C. K. (1969) Third parties in twentieth century American politics, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/9989/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk "THIRD PARTIES IN TWENTIETH CENTURY AMERICAN POLITICS" THESIS PGR AS M. A. DEGREE PRESENTED EOT CK. SOMBER (ST.CUTHBERT«S) • JTJLT, 1969. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS. INTRODUCTION. PART 1 - THE PROGRESSIVE PARTIES. 1. THE "BOLL MOOSE" PROQRESSIVES. 2. THE CANDIDACY CP ROBERT M. L& FQLLETTE. * 3. THE PEOPLE'S PROGRESSIVE PARTI. PART 2 - THE SOCIALIST PARTY OF AMERICA* PART 3 * PARTIES OF LIMITED GEOGRAPHICAL APPEAL. -

Tennessee, the Solid South, and the 1952 Presidential Election

University of Mississippi eGrove Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors Theses Honors College) Spring 5-9-2020 Y'all Like Ike: Tennessee, the Solid South, and the 1952 Presidential Election Cameron N. Regnery University of Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis Part of the American Politics Commons, Political History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Regnery, Cameron N., "Y'all Like Ike: Tennessee, the Solid South, and the 1952 Presidential Election" (2020). Honors Theses. 1338. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis/1338 This Undergraduate Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College) at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Y’ALL LIKE IKE: TENNESSEE, THE SOLID SOUTH, AND THE 1952 PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION by Cameron N. Regnery A thesis submitted to the faculty of The University of Mississippi in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College. Oxford April 2020 Approved by: __________________________________ Advisor: Dr. Darren Grem __________________________________ Reader: Dr. Rebecca Marchiel __________________________________ Reader: Dr. Conor Dowling © 2020 Cameron N. Regnery ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my parents for supporting me both in writing this thesis and throughout my time at Ole Miss. I would like to thank my thesis advisor, Dr. Darren Grem, for helping me with both the research and writing of this thesis. It would certainly not have been possible without him. -

Rum, Romanism, and Virginia Democrats: the Party Leaders and the Campaign of 1928 James R

Old Dominion University ODU Digital Commons History Faculty Publications History 1982 Rum, Romanism, and Virginia Democrats: The Party Leaders and the Campaign of 1928 James R. Sweeney Old Dominion University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/history_fac_pubs Part of the American Politics Commons, Political History Commons, and the United States History Commons Repository Citation Sweeney, James R., "Rum, Romanism, and Virginia Democrats: The aP rty Leaders and the Campaign of 1928" (1982). History Faculty Publications. 6. https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/history_fac_pubs/6 Original Publication Citation Sweeney, J. R. (1982). Rum, Romanism, and Virginia democrats: The ap rty leaders and the campaign of 1928. Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, 90(4), 403-431. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History at ODU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of ODU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Virginia Magazine OF HISTORY AND BIOGRAPHY ft Vol. 90 October 1982 No. 4 w *fc^?i*L> U&J*L> U*lJfcL> OfoJtU U&JRj im4b <J*IJ?L> ?J?im^ U&J&> 4?ft,t~JD* RUM, ROMANISM, AND VIRGINIA DEMOCRATS The Party Leaders and the Campaign of 1928 hy James R. Sweeney* 'The most exciting and most bitterly fought State-wide campaign held in Virginia since the days of General William Mahone and the Readjusters." In these words the Richmond Times-Dispatch described the just-concluded campaign on election day morning, 6 November 1928. Democratic nomi- nees had carried Virginia in every presidential election since 1872; how- ever, in predominantly agricultural, dry, Protestant Virginia a political upheaval was a distinct possibility in 1928. -

COLORADO DEPARTMENT of STATE, Petitioner, V

No. 19-518 In the Supreme Court of the United States COLORADO DEPARTMENT OF STATE, Petitioner, v. MICHEAL BACA, POLLY BACA, AND ROBERT NEMANICH, Respondents. On Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit BRIEF OF AMICUS CURIAE COLORADO REPUBLICAN COMMITTEE IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONER JULIAN R. ELLIS, JR. Counsel of Record CHRISTOPHER O. MURRAY BROWNSTEIN HYATT FARBER SCHRECK, LLP 410 17th Street, Suite 2200 Denver, CO 80202 (303) 223-1100 [email protected] Attorneys for Amicus Curiae i QUESTIONS PRESENTED 1. Whether a presidential elector who is prevent- ed by their appointing State from casting an Elec- toral College ballot that violates state law lacks standing to sue their appointing State because they hold no constitutionally protected right to exercise discretion. 2. Does Article II or the Twelfth Amendment for- bid a State from requiring its presidential electors to follow the State’s popular vote when casting their Electoral College ballots. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page QUESTIONS PRESENTED ..................................... i TABLE OF CONTENTS .......................................... ii TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ................................... iii INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE ......................... 1 SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT ......................... 2 ARGUMENT .............................................................. 5 I. Political Parties’ Involvement in Selecting Nominees for Presidential Elector Is Constitutionally Sanctioned and Ubiquitous. ..... 5 A. States have plenary power over the appointment of presidential electors. ............ 5 B. Ray v. Blair expressly approved of pledges to political parties by candidates for presidential elector. ................................ 14 II. State Political Parties Must Be Allowed to Enforce Pledges to the Party by Candidates for Presidential Elector. ..................................... 17 CONCLUSION ......................................................... 22 iii TABLE OF AUTHORITIES Page(s) Cases Cal. -

Why Did the Democrats Lose the South? Bringing New Data to an Old Debate

Why did the Democrats Lose the South? Bringing New Data to an Old Debate Ilyana Kuziemko and Ebonya Washington∗ September 17, 2016 Abstract A long-standing debate in political economy is whether voters are driven primar- ily by economic self-interest or by less pecuniary motives such as ethnocentrism. Using newly available data, we reexamine one of the largest partisan shifts in a modern democ- racy: Southern whites' exodus from the Democratic Party, concentrated in the 1960s. Combining high-frequency survey data and textual newspaper analysis, we show that defection among racially conservative whites explains all (three-fourths) of the large decline in white Southern Democratic identification between 1958 and 1980 (2000). Racial attitudes also predict whites' partisan shifts earlier in the century. Relative to recent work, we find a much larger role for racial views and essentially no role for income growth or (non-race-related) policy preferences in explaining why Democrats \lost" the South. JEL codes: D72, H23, J15, N92 ∗We thank Frank Newport and Jeff Jones for answering our questions about the Gallup data. We are grateful to Alberto Alesina, Daron Acemoglu, Bill Collins, Marvin Danielson, Claudia Goldin, Matt Gentzkow, Alex Mas, Adrian Matray, Suresh Naidu, Jesse Shapiro, Seth Stephens-Davidowitz, Gavin Wright and seminar participants at the University of Chicago, Middlebury, NBER Summer Institute's Political Economy Workshop, the National Tax Association, NYU, Pomona, Princeton, Stanford SITE, University of Toronto, UBC, UCLA and Yale's CSAP Summer conference, par- ticularly discussants Georgia Kernell, Nolan McCarthy and Maya Sen for valuable comments and feedback. Khurram Ali, Jimmy Charit´e,Jos´ephineGantois, Keith Gladstone, Meredith Levine, Chitra Marti, Jenny Shen, Timothy Toh and Tammy Tseng provided truly exceptional research assistance. -

President's Trip to Atlanta 1/20/78

President’s Trip to Atlanta, 1/20/78 Folder Citation: Collection: Office of Staff Secretary; Series: Presidential Files; Folder: President’s Trip to Atlanta, 1/20/78; Container 60 To See Complete Finding Aid: http://www.jimmycarterlibrary.gov/library/findingaids/Staff_Secretary.pdf .................. I "'trt••• ....(JIG ... THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINGTON '~ ' VISIT TO ATLANTA, PLAINS, AND SAINT SIMONS ISLAND, GEORGIA January ·20 - 23, · 1978 FRIDAY - JANUARY 20, 1978 DAY # 1 Departure: 2i05 P.M. From: · Tim .Kraft SEQUENCE 2:05 p .·m. You board helicopter on South Lawn and depart en route Andrews Air Force Base.' PRESIDENTIAL GUEST James Mcintyre,· Director, OMB 2:25 p.m. Helicopter arrives Andrews AFB. Board Air Force One. PRESIDENTIAL GUESTS Ambassador and Mrs. Robert Strauss. Senator Wendell H. Ford Senator Sam Nunn Senator James R. Sasser Senator Herman E. Talmadge Congressman James c. Corman '~' . Congressman Billy Lee Evans Congressman Edgar L. Jenkins ,· ,.· _secretqry James Schlesinger Mr • HUbert ··L _. 'ffarr is . ·~~· ·- ---,·~· .. , Jr. ... J1~~~~ry Beazley .~r-...: Ben Brown . __ -··-·. - ... ) ..- !>ir. Charles Manatt Ms. Nancy Moore L ·~ :... ... lhiriia.~-..- J .. ~ .......pa •• 2. <:. ·FRIDAY - JANUARY 20, 1978 -··C-Ontinued 2":.3p .P•,ll•, .. · -:-:-., 9 , .·• ,..,., il~¥" Eo~c_~: ,One departs Andrews Air Force --~ .. •·....... :..;_., • • •• , • ..J ..... ,·sase en.route Dobbins Air Force Base, "i. '?;'.' ~::-.t· -~ J ,G..-: ..:~~~~-~f~·~.;- ,. :_. ·c.·· .. r ·-. ···-(Flying Time: l hour, 35 minutes) V0l.F-C.~~·:.:. [''-i.: r1·""; • '4:05 p.m •.. l.. ·'J,·~c .:.; ' ~ ~..;..fcrl'9X:~ One arr1.ves Dobbins Air Force Base. _,. h ...... 1 :: -;· !..'f~ ...... _,· -~·h ... ::~ ., :;.~9\l,Wi~l be met by: ... ~..:.. ..,~:· -~ 'c.~·~~ '.: ~'1 ...... ..;' J •. ~~·.:~.. : : . .. ~.r- -~ r· --~; ·· __ ·.. ; ... 1~Y~~'?r·. ~9rge Busbee ., ~ ~ .. -

The Dixiecrat Movement of 1948: a Study in Political Conflict

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1972 The Dixiecrat Movement of 1948: A Study in Political Conflict Michael Terrence Lavin College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Political Science Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Lavin, Michael Terrence, "The Dixiecrat Movement of 1948: A Study in Political Conflict" (1972). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539624778. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-e3mx-tj71 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE DIXIECRAT MOVEMENT OF 1948 A STUDY IN POLITICAL CONFLICT A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Government The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Michael Terrence Lavin 1972 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Author Approved, May, 1972 Warner Moss 0 - Roger Sjnith V S t Jac^Edwards ii TABLE OP CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .......................... iv / LIST OF T A B L E S ..................................... v LIST OP FIGURES ............. Vii ABSTRACT .......... ' . viii INTRODUCTION . ..... 2 CHAPTER I. THE CHARACTERISTICS OP THE BLACK BELT REGIONS OF THE AMERICAN SOUTH ..... 9 CHAPTER II. THE CHARACTERISTICS OP THE DIXIECRAT MOVEMENT OP 19^8 .......... -

Download Download

134 Reviews Yet this does not mean that dependency theorists argue that conflict grows from a power imbalance. Barbieri concludes that instead of power imbalances result- ing in greater conflict between states, states with symmetric ties were in fact more likely to experience conflict. In the end, while Barbieri has made a signif- icant contribution to the field, she is willing to admit that while her findings are useful, questions still remain, and more research is needed to understand the exact nature of the interaction between trade and conflict. It is a noble admission from a scholar who has provided a spirited insight into this complex and impor- tant field. Z%e Liberal Illusion is not without its shortcomings, however. Although it is very dense, the book is, in fact, rather short, running to only 137 pages of text. There are sections in the book which provide some excellent analysis on how the Great Powers related to each other in terms of conflict and trade over the last century: The reader would appreciate more of this insight. Moreover, although it is brief, the book devotes considerable detail to explaining the nuances of Barbieri's methodology. While important, readers would likely have traded the extensive equations for more examples that actually address real world relation- ships and conflict. As a result, the books reads like a dissertation (it was), which, while brilliant, could have been expanded and refined somewhat. It also might be appreciated more by political theorists than historians, who will find the rig- orous methodology and extensive data somewhat removed from historical events. -

Factionalism in the Democratic Party 1936-1964

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Undergraduate Honors Theses Student Works 1-2019 Factionalism in the Democratic Party 1936-1964 Seth Manning Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/honors Part of the American Politics Commons, Labor History Commons, Political History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Manning, Seth, "Factionalism in the Democratic Party 1936-1964" (2019). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 477. https://dc.etsu.edu/honors/477 This Honors Thesis - Withheld is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Factionalism in the Democratic Party 1936-1964 By Seth F. Manning An Undergraduate Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the University Honors Scholars Program Honors College Mentor: Dr. Andrew Battista East Tennessee State University 1 Abstract The period of 1936-1964 in the Democratic Party was one of intense factional conflict between the rising Northern liberals, buoyed by FDR’s presidency, and the Southern conservatives who had dominated the party for a half-century. Intertwined prominently with the struggle for civil rights, this period illustrates the complex battles that held the fate of other issues such as labor, foreign policy, and economic ideology in the balance. This thesis aims to explain how and why the Northern liberal faction came to defeat the Southern conservatives in the Democratic Party through a multi-faceted approach examining organizations, strategy, arenas of competition, and political opportunities of each faction.