The Red Scare in Texas Higher Education, 1936-1958

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

75 Years of Hoblitzelle Foundation

The Philanthropy of Karl Hoblitzelle and the first years of 1 Karl Hoblitzelle 2 3 The Philanthropy of Karl Hoblitzelle & the First 75 years of Hoblitzelle Foundation Preface ............................................................................................................. 4 Chapter 1 ......................................................................................................... 5 Founding in 1942 to the early 1950s Chapter 2 ...................................................................................................... 13 Three brief biographies - The Story of Karl Hoblitzelle by Lynn Harris ........................................ 13 Forty Years of Community Service by Don Hinga ................................. 55 The Vision of Karl Hoblitzelle by Harry Hunt Ransom ......................... 87 Chapter 3 ..................................................................................................... 102 Establishment of the Foundation as a Corporation through Hoblitzelle’s death in 1967 Chapter 4 ..................................................................................................... 109 1968 through 1985 Chapter 5 ..................................................................................................... 113 1986 through 2004 Chapter 6 ..................................................................................................... 117 2005 to 2017 Chapter 7 ..................................................................................................... 121 Hoblitzelle -

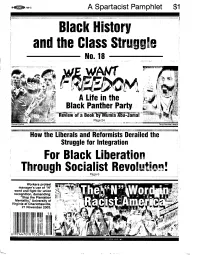

Black History and the Class Struggle

®~759.C A Spartacist Pamphlet $1 Black History i! and the Class Struggle No. 18 Page 24 ~iI~i~·:~:f!!iI'!lIiAI_!Ii!~1_&i 1·li:~'I!l~~.I_ :lIl1!tl!llti:'1!):~"1i:'S:':I'!mf\i,ri£~; : MINt mm:!~~!!)rI!t!!i\i!Ui\}_~ How the Liberals and Reformists Derailed the Struggle for Integration For Black Liberation Through Socialist Revolution! Page 6 VVorkers protest manager's use of "N" word and fight for union recognition, demanding: "Stop the Plantation Mentality," University of Virginia at Charlottesville, , 21 November 2003. I '0 ;, • ,:;. i"'l' \'~ ,1,';; !r.!1 I I -- - 2 Introduction Mumia Abu-Jamal is a fighter for the dom chronicles Mumia's political devel Cole's article on racism and anti-woman oppressed whose words teach powerful opment and years with the Black Panther bigotry, "For Free Abortion on Demand!" lessons and rouse opposition to the injus Party, as well as the Spartacist League's It was Democrat Clinton who put an "end tices of American capitalism. That's why active role in vying to win the best ele to welfare as we know it." the government seeks to silence him for ments of that generation from black Nearly 150 years since the Civil War ever with the barbaric death penaIty-a nationalism to revolutionary Marxism. crushed the slave system and won the legacy of slavery-,-Qr entombment for life One indication of the rollback of black franchise for black people, a whopping 13 for a crime he did not commit. The frame rights and the absence of militant black percent of black men were barred from up of Mumia Abu-Jamal represents the leadership is the ubiquitous use of the voting in the 2004 presidential election government's fear of the possibility of "N" word today. -

75 Years of Vision the Lasting Gift of Southwestern Medical Foundation Part I: 1939 to 1979 Turn of the Century Postcard of Main Street, Downtown Dallas

75 Years of Vision The Lasting Gift of Southwestern Medical Foundation Part I: 1939 to 1979 Turn of the century postcard of Main Street, downtown Dallas. 1890 Eighteen-year-old Edward Cary comes to Dallas to work at his brother’s medical supply business. 75 YEARS OF VISION: THE LASTING GIFT A MEDICAL WILDERNESS 1890 TO 1939 I n 1890, Dallas was a growing center of commerce for North Texas. The population had gone from roughly 400 people in 1850 to nearly 38,000. The city was thriving, but its potential as a leading American city was far from understood. The medical care offered in Dallas was primitive. Science-based medicine was in its infancy. Dallas doctors had not yet accepted the germ theory of disease. Surgical hygiene and the sterilization of medical instruments were virtually nonexistent. The average life expectancy was just 47 years. Infections such as pneumonia, diarrhea, influenza and tuberculosis were leading causes of death. Yellow fever, scarlet fever and dengue fever were common. Patients with contagious diseases were isolated, often along with their families, in “pest houses” where they remained quarantined without care until they died or it could be shown they no longer had the illness. While qualified and notable doctors were practicing medicine in Dallas at the time, many more were poorly trained. Most received only basic training from small medical schools, which required only one to two years of study following three years of high school. While no photos of Dallas’ first Fake medical licenses were common. An MD degree could be conferred “pest houses” exist, this early 1900s building also served to quarantine by return postage in exchange for a letter of intent and a fee of fifteen dollars. -

Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library & Museum Audiovisual

Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library & Museum Audiovisual Department Robert B. Anderson Photographs 2004-7-1--1320 2004-7-1 Portrait of Major Robert Anderson, a Civil War soldier and West Point graduate. This is a copy of a Matthew Brady photo. Photo sent by E. Robert Anderson of San Diego, California, on July 10, 1953. Copyright: public domain. One B&W 6 ½ x 9 print. 2004-7-2—6 Five photographs of a landing field near Tipton, Oklahoma, taken from the air. Photo sent by Frank Beer of Phoenix, Arizona on December 15, 1954. Copyright: Norma Greene Studio; Vernon, Texas. Five B&W 8 x 10 prints. 2004-7-7 Photo of Alvin L. Borchardt, Jr., of Vernon, Texas, a U.S. Air Force pilot. Photo sent by Borchardt on March 29, 1955. Copyright: unknown. One B&W 2 ½ x 3 ½ print. 2004-7-8 Photo of Leon H. Brown, Jr. of Mission, Texas, a jet pilot at Williams Air Force Base in Chandler, Arizona. Photo sent by Brown’s mother, Mrs. Leon H. Brown on June 6, 1954. Copyright: unknown. One B&W 3 x 5 print. 2004-7-9 Photo of the staff of Rheumatic Fever Research Institute of Chicago, Illinois. Photo sent by Alvin F. Coburn, director of the Institute on March 17, 1954. Copyright: Evanston [Illinois] Photographic Service. One B&W 8 x 10 print. 2004-7-10—12 Three photos of the children of Dr. Alvin Coburn of Chicago, Illinois. Photo sent by Alvin F. Coburn on September 8, 1954. Copyright: unknown. Three B&W 2 ½ x 3 ½ prints. -

QUARTERLY of Local Architecture & Preservation

Six Dollars Spring - Summer 1993 THE HISTORIC HUNTSVILLE QUARTERLY Of Local Architecture & Preservation HAL PRESENTS HUNTSVILLE HISTORIC HUNTSVILLE FOUNDATION Founded 1974 Officers for 1993-1994 Suzanne O’Connor............................................................ Chairman Suzi Bolton.............................................................. Vice-Chairman Susan Gipson..................................................................... Secretary Toney Daly........................................................................ Treasurer Gerald Patterson (Immediate Past Chairman)............. Ex-Officio Lynn Jones............................................... Management Committee Elise H. Stephens.....................................................................Editor Board of Directors Ralph Allen William Lindberg Ron Baslock Gayle Milberger Rebecca Bergquist Bill Nance Wm. Verbon Black Norma Oberlies Suzi Bolton Wilma Phillips Glenda Bragg Richard Pope Mary A. Coulter Dale Rhoades James Cox Susan Sanderson Toney Daly Stephanie Sherman Carle ne Elrod Malcolm Tarkington Henry M. Fail, Jr. Mary F. Thomas Susan Gipson Richard Van Valkenburgh Ann Harrison Janet Watson John Rison Jones, Jr. Sibyl Wilkinson Walter Kelley Eugene Worley COVER: Watercolor by Cynthia Massey Parsons. “Harrison Bros. Hardware” — $350 THE HISTORIC HUNTSVILLE QUARTERLY of Local Architecture and Preservation Vol. XIV, Nos. 1&2 Spring-Summer— 1993 CONTENTS From The Editor.........................................................................2 From The -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses Third parties in twentieth century American politics Sumner, C. K. How to cite: Sumner, C. K. (1969) Third parties in twentieth century American politics, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/9989/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk "THIRD PARTIES IN TWENTIETH CENTURY AMERICAN POLITICS" THESIS PGR AS M. A. DEGREE PRESENTED EOT CK. SOMBER (ST.CUTHBERT«S) • JTJLT, 1969. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS. INTRODUCTION. PART 1 - THE PROGRESSIVE PARTIES. 1. THE "BOLL MOOSE" PROQRESSIVES. 2. THE CANDIDACY CP ROBERT M. L& FQLLETTE. * 3. THE PEOPLE'S PROGRESSIVE PARTI. PART 2 - THE SOCIALIST PARTY OF AMERICA* PART 3 * PARTIES OF LIMITED GEOGRAPHICAL APPEAL. -

COLORADO DEPARTMENT of STATE, Petitioner, V

No. 19-518 In the Supreme Court of the United States COLORADO DEPARTMENT OF STATE, Petitioner, v. MICHEAL BACA, POLLY BACA, AND ROBERT NEMANICH, Respondents. On Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit BRIEF OF AMICUS CURIAE COLORADO REPUBLICAN COMMITTEE IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONER JULIAN R. ELLIS, JR. Counsel of Record CHRISTOPHER O. MURRAY BROWNSTEIN HYATT FARBER SCHRECK, LLP 410 17th Street, Suite 2200 Denver, CO 80202 (303) 223-1100 [email protected] Attorneys for Amicus Curiae i QUESTIONS PRESENTED 1. Whether a presidential elector who is prevent- ed by their appointing State from casting an Elec- toral College ballot that violates state law lacks standing to sue their appointing State because they hold no constitutionally protected right to exercise discretion. 2. Does Article II or the Twelfth Amendment for- bid a State from requiring its presidential electors to follow the State’s popular vote when casting their Electoral College ballots. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page QUESTIONS PRESENTED ..................................... i TABLE OF CONTENTS .......................................... ii TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ................................... iii INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE ......................... 1 SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT ......................... 2 ARGUMENT .............................................................. 5 I. Political Parties’ Involvement in Selecting Nominees for Presidential Elector Is Constitutionally Sanctioned and Ubiquitous. ..... 5 A. States have plenary power over the appointment of presidential electors. ............ 5 B. Ray v. Blair expressly approved of pledges to political parties by candidates for presidential elector. ................................ 14 II. State Political Parties Must Be Allowed to Enforce Pledges to the Party by Candidates for Presidential Elector. ..................................... 17 CONCLUSION ......................................................... 22 iii TABLE OF AUTHORITIES Page(s) Cases Cal. -

HOUSE of REPRESENTATIVES-Thursday, January 30, 1975

1918 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD- HOUSE Januar-y 30, 1975 MEMBERSHIP OF SELECT two leaders are reconciled on Monday tion of routine business for not to exceed COMMITI'EE next under the standing order, Mr. BEALL 25 minutes with statements therein lim Mr. ROBERT C. BYRD. Mr. President, be recognized for not to exceed 15 min ited to 5 minutes each. the leadership on both sides of the utes; and that there then be a period for As to votes on Monday, there is always aisle have selected the members-and the transaction of routine morning busi the possibility, of course. I can say noth they have been approved by the Senate ness of not to exceed 45 minutes, the ing definite beyond this point. of the Select Committee To Study statements therein to be limited to 5 Governmental Operations With Respect minutes each. to Intelligence Activities. It is my un The PRESIDING OFFICER. Without ADJOURNMENT UNTIL MONDAY, derstanding that Mr. CHURCH has been objection , it is so ordered. FEBRUARY 3, 1975 selected to be the chairman of that com mittee and that Mr. ToWER has been se Mr. ROBERT C. BYRD. Mr. President, lected to be the vice chairman of that PROGRAM if there be no further business to come before the Senate, I move, in accordance committee. I make that statement fo"t Mr. ROBERT C. BYRD. Mr. President, the record. with the previous order, that the Senate the Senate will next convene on Monday stand in adjournment until the hour of at 12 noon. After the two leaders, or 12 noon on Monday next. -

Why Did the Democrats Lose the South? Bringing New Data to an Old Debate

Why did the Democrats Lose the South? Bringing New Data to an Old Debate Ilyana Kuziemko and Ebonya Washington∗ September 17, 2016 Abstract A long-standing debate in political economy is whether voters are driven primar- ily by economic self-interest or by less pecuniary motives such as ethnocentrism. Using newly available data, we reexamine one of the largest partisan shifts in a modern democ- racy: Southern whites' exodus from the Democratic Party, concentrated in the 1960s. Combining high-frequency survey data and textual newspaper analysis, we show that defection among racially conservative whites explains all (three-fourths) of the large decline in white Southern Democratic identification between 1958 and 1980 (2000). Racial attitudes also predict whites' partisan shifts earlier in the century. Relative to recent work, we find a much larger role for racial views and essentially no role for income growth or (non-race-related) policy preferences in explaining why Democrats \lost" the South. JEL codes: D72, H23, J15, N92 ∗We thank Frank Newport and Jeff Jones for answering our questions about the Gallup data. We are grateful to Alberto Alesina, Daron Acemoglu, Bill Collins, Marvin Danielson, Claudia Goldin, Matt Gentzkow, Alex Mas, Adrian Matray, Suresh Naidu, Jesse Shapiro, Seth Stephens-Davidowitz, Gavin Wright and seminar participants at the University of Chicago, Middlebury, NBER Summer Institute's Political Economy Workshop, the National Tax Association, NYU, Pomona, Princeton, Stanford SITE, University of Toronto, UBC, UCLA and Yale's CSAP Summer conference, par- ticularly discussants Georgia Kernell, Nolan McCarthy and Maya Sen for valuable comments and feedback. Khurram Ali, Jimmy Charit´e,Jos´ephineGantois, Keith Gladstone, Meredith Levine, Chitra Marti, Jenny Shen, Timothy Toh and Tammy Tseng provided truly exceptional research assistance. -

The Dixiecrat Movement of 1948: a Study in Political Conflict

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1972 The Dixiecrat Movement of 1948: A Study in Political Conflict Michael Terrence Lavin College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Political Science Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Lavin, Michael Terrence, "The Dixiecrat Movement of 1948: A Study in Political Conflict" (1972). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539624778. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-e3mx-tj71 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE DIXIECRAT MOVEMENT OF 1948 A STUDY IN POLITICAL CONFLICT A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Government The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Michael Terrence Lavin 1972 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Author Approved, May, 1972 Warner Moss 0 - Roger Sjnith V S t Jac^Edwards ii TABLE OP CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .......................... iv / LIST OF T A B L E S ..................................... v LIST OP FIGURES ............. Vii ABSTRACT .......... ' . viii INTRODUCTION . ..... 2 CHAPTER I. THE CHARACTERISTICS OP THE BLACK BELT REGIONS OF THE AMERICAN SOUTH ..... 9 CHAPTER II. THE CHARACTERISTICS OP THE DIXIECRAT MOVEMENT OP 19^8 .......... -

H. Doc. 108-222

SEVENTY-SEVENTH CONGRESS JANUARY 3, 1941, TO JANUARY 3, 1943 FIRST SESSION—January 3, 1941, to January 2, 1942 SECOND SESSION—January 5, 1942, 1 to December 16, 1942 VICE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES 2—JOHN N. GARNER, 3 of Texas; HENRY A. WALLACE, 4 of Iowa PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE OF THE SENATE—PAT HARRISON, 5 of Mississippi; CARTER GLASS, 6 of Virginia SECRETARY OF THE SENATE—EDWIN A. HALSEY, of Virginia SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE SENATE—CHESLEY W. JURNEY, of Texas SPEAKER OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES—SAM RAYBURN, 7 of Texas CLERK OF THE HOUSE—SOUTH TRIMBLE, 8 of Kentucky SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE HOUSE—KENNETH ROMNEY, of Montana DOORKEEPER OF THE HOUSE—JOSEPH J. SINNOTT, of Virginia POSTMASTER OF THE HOUSE—FINIS E. SCOTT ALABAMA ARKANSAS Albert E. Carter, Oakland SENATORS John H. Tolan, Oakland SENATORS John Z. Anderson, San Juan Bautista Hattie W. Caraway, Jonesboro John H. Bankhead II, Jasper Bertrand W. Gearhart, Fresno John E. Miller, 11 Searcy Lister Hill, Montgomery Alfred J. Elliott, Tulare George Lloyd Spencer, 12 Hope Carl Hinshaw, Pasadena REPRESENTATIVES REPRESENTATIVES Jerry Voorhis, San Dimas Frank W. Boykin, Mobile E. C. Gathings, West Memphis Charles Kramer, Los Angeles George M. Grant, Troy Wilbur D. Mills, Kensett Thomas F. Ford, Los Angeles Henry B. Steagall, Ozark Clyde T. Ellis, Bentonville John M. Costello, Hollywood Sam Hobbs, Selma Fadjo Cravens, Fort Smith Leland M. Ford, Santa Monica Joe Starnes, Guntersville David D. Terry, Little Rock Lee E. Geyer, 14 Gardena Pete Jarman, Livingston W. F. Norrell, Monticello Cecil R. King, 15 Los Angeles Walter W. -

The Power of the Dixiecrats, Spring 1963

THE POWER OF--THE--Dl:X.IECRATS_,.--by-T-om·Hayden The last major stand of the Dixiecrats may be occurring in the 1963 hearings on the Kennedy civil rights bill • . Behind the wild accusations of communism in the civil rights movement and the trumpeted defense of prop~rty rights is a thinning legion of the Old Guard, How long will the Dixiecrat be such· a shrill and decisive force on the American political scene? The answer requir_es a review of Southern history, ideology, the policy of the New Frontier, and the international and national pres sures to do something about America's sore racial problem. The conclusion seems to be that the formal walls of segregation are being smashed, but the ~ite Man's Bur den can be carried in more subtle ways--as the people of the North we 11 knm-v, Dixiecrats in history For more th<m a generation the Demoo:pa,tie-~~-- -has - .been split ·deeply bet1r1een its Southern and Northern wings,. .the-former a safe bastion of racist conserV'atism and the latter a changing bloc of liberal reformers, The conflict is not new, and can- , _not be unde!'~~ood p~erly unless it is traced from the period of the :New Deal, In the 1936 election-the Democratic tide vJas rolling. Roosevelt brought to power 334 Democrats in the House against 89 Republicans. In the Senate 75 Democrats took seats against only 17 Republicans. The President's inaugural address promised the greatest liberal advances of this century: III see one-third of a nation ill-housed, ill-clad, ill-nouri9hed •••• It is not in despair that I paint you that picture.