Bound-Variable Pronouns and the Semantics of Number Hotze Rullmann University of Calgary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Questions Under Discussion: from Sentence to Discourse∗

Questions under Discussion: From sentence to discourse∗ Anton Benz Katja Jasinskaja July 14, 2016 Abstract Questions under discussion (QUD) is an analytic tool that has recently become more and more popular among linguists and language philosophers as a way to characterize how a sentence fits in its context. The idea is that each sentence in discourse addresses a (of- ten implicit) QUD either by answering it, or by bringing up another question that can help answering that QUD. The linguistic form and the interpretation of a sentence, in turn, may depend on the QUD it addresses. The first proponents of the QUD approach (von Stut- terheim & Klein, 1989; van Kuppevelt, 1995) thought of it as a general approach to the analysis of discourse structure where structural relations between sentences in a coherent discourse are understood in terms of relations between questions they address. However, the idea did not find broad application in discourse structure analysis, where theories aiming at logical discourse representations are predominantly based on the notion of coherence re- lations (Mann & Thompson, 1988; Hobbs, 1985; Asher & Lascarides, 2003). The problem of finding overt markers for QUDs means that they are also difficult to utilize for quanti- tative measures of discourse coherence (McNamara et al., 2010). At the same time QUD proved useful in the analysis of a wide range of linguistic phenomena including accentua- tion, discourse particles, presuppositions and implicatures. The goal of this special issue is to bring together cutting-edge research that demonstrates the success of QUD in linguistics and the need for the development of a comprehensive model of discourse coherence that incorporates the notion of QUD as its integral part. -

Notes on Generalized Quantifiers

Notes on generalized quantifiers Ann Copestake ([email protected]), Computer Lab Copyright c Ann Copestake, 2001–2012 These notes are (minimally) adapted from lecture notes on compositional semantics used in a previous course. They are provided in order to supplement the notes from the Introduction to Natural Language Processing module on compositional semantics. 1 More on scope and quantifiers In the introductory module, we restricted ourselves to first order logic (or subsets of it). For instance, consider: (1) every big dog barks 8x[big0(x) ^ dog0(x) ) bark0(x)] This is first order because all predicates take variables denoting entities as arguments and because the quantifier (8) and connective (^) are part of standard FOL. As far as possible, computational linguists avoid the use of full higher-order logics. Theorem-proving with any- thing more than first order logic is problematic in general (though theorem-proving with FOL is only semi-decidable and that there are some ways in which higher-order constructs can be used that don’t make things any worse). Higher order sets in naive set theory also give rise to Russell’s paradox. Even without considering inference or denotation, higher-order logics cause computational problems: e.g., when deciding whether two higher order expressions are potentially equivalent (higher-order unification). However, we have to go beyond standard FOPC to represent some constructions. We need modal operators such as probably. I won’t go into the semantics of these in detail, but we can represent them as higher-order predicates. For instance: probably0(sleep0(k)) corresponds to kitty probably sleeps. -

Nouns, Adjectives, Verbs, and Adverbs

Unit 1: The Parts of Speech Noun—a person, place, thing, or idea Name: Person: boy Kate mom Place: house Minnesota ocean Adverbs—describe verbs, adjectives, and other Thing: car desk phone adverbs Idea: freedom prejudice sadness --------------------------------------------------------------- Answers the questions how, when, where, and to Pronoun—a word that takes the place of a noun. what extent Instead of… Kate – she car – it Many words ending in “ly” are adverbs: quickly, smoothly, truly A few other pronouns: he, they, I, you, we, them, who, everyone, anybody, that, many, both, few A few other adverbs: yesterday, ever, rather, quite, earlier --------------------------------------------------------------- --------------------------------------------------------------- Adjective—describes a noun or pronoun Prepositions—show the relationship between a noun or pronoun and another word in the sentence. Answers the questions what kind, which one, how They begin a prepositional phrase, which has a many, and how much noun or pronoun after it, called the object. Articles are a sub category of adjectives and include Think of the box (things you have do to a box). the following three words: a, an, the Some prepositions: over, under, on, from, of, at, old car (what kind) that car (which one) two cars (how many) through, in, next to, against, like --------------------------------------------------------------- Conjunctions—connecting words. --------------------------------------------------------------- Connect ideas and/or sentence parts. Verb—action, condition, or state of being FANBOYS (for, and, nor, but, or, yet, so) Action (things you can do)—think, run, jump, climb, eat, grow A few other conjunctions are found at the beginning of a sentence: however, while, since, because Linking (or helping)—am, is, are, was, were --------------------------------------------------------------- Interjections—show emotion. -

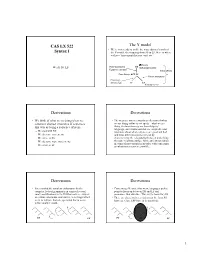

CAS LX 522 Syntax I the Y Model

CAS LX 522 The Y model • We’re now ready to tackle the most abstract branch of Syntax I the Y-model, the mapping from SS to LF. Here is where we have “movement that you can’t see”. θ Theory Week 10. LF Overt movement, DS Subcategorization Expletive insertion X-bar theory Case theory, EPP SS Covert movement Phonology/ Morphology PF LF Binding theory Derivations Derivations • We think of what we’re doing when we • The steps are not necessarily a reflection of what construct abstract structures of sentences we are doing online as we speak—what we are this way as being a sequence of steps. doing is characterizing our knowledge of language, and it turns out that we can predict our – We start with DS intuitions about what sentences are good and bad – We do some movements and what different sentences mean by – We arrive at SS characterizing the relationship between underlying – We do some more movements thematic relations, surface form, and interpretation in terms of movements in an order with constraints – We arrive at LF on what movements are possible. Derivations Derivations • It seems that the simplest explanation for the • Concerning SS, under this view, languages pick a complex facts of grammar is in terms of several point to focus on between DS and LF and small modifications to the DS that each are subject pronounce that structure. This is (the basis for) SS. to certain constraints, sometimes even things which • There are also certain restrictions on the form SS seem to indicate that one operation has to occur has (e.g., Case, EPP have to be satisfied). -

Minimal Pronouns, Logophoricity and Long-Distance Reflexivisation in Avar

Minimal pronouns, logophoricity and long-distance reflexivisation in Avar* Pavel Rudnev Revised version; 28th January 2015 Abstract This paper discusses two morphologically related anaphoric pronouns inAvar (Avar-Andic, Nakh-Daghestanian) and proposes that one of them should be treated as a minimal pronoun that receives its interpretation from a λ-operator situated on a phasal head whereas the other is a logophoric pro- noun denoting the author of the reported event. Keywords: reflexivity, logophoricity, binding, syntax, semantics, Avar 1 Introduction This paper has two aims. One is to make a descriptive contribution to the crosslin- guistic study of long-distance anaphoric dependencies by presenting an overview of the properties of two kinds of reflexive pronoun in Avar, a Nakh-Daghestanian language spoken natively by about 700,000 people mostly living in the North East Caucasian republic of Daghestan in the Russian Federation. The other goal is to highlight the relevance of the newly introduced data from an understudied lan- guage to the theoretical debate on the nature of reflexivity, long-distance anaphora and logophoricity. The issue at the heart of this paper is the unusual character of theanaphoric system in Avar, which is tripartite. (1) is intended as just a preview with more *The present material was presented at the Utrecht workshop The World of Reflexives in August 2011. I am grateful to the workshop’s audience and participants for their questions and comments. I am indebted to Eric Reuland and an anonymous reviewer for providing valuable feedback on the first draft, as well as to Yakov Testelets for numerous discussions of anaphora-related issues inAvar spanning several years. -

Relative Clause Attachment and Anaphora: a Case for Short Binding

Relative Clause Attachment and Anaphora: A Case for Short Binding Rodolfo Delmonte Ca' Garzoni-Moro, San Marco 3417, Università "Ca Foscari", 30124 - VENEZIA E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Relative clause attachment may be triggered by binding requirements imposed by a short anaphor contained within the relative clause itself: in case more than one possible attachment site is available in the previous structure, and the relative clause itself is extraposed, a conflict may arise as to the appropriate s/c-structure which is licenced by grammatical constraints but fails when the binding module tries to satisfy the short anaphora local search for a bindee. 1 Introduction It is usually the case that anaphoric and pronominal binding take place after the structure building phase has been successfully completed. In this sense, c-structure and f-structure in the LFG framework - or s-structure in the chomskian one - are a prerequisite for the carrying out of binding processes. In addition, they only interact in a feeding relation since binding would not be possibly activated without a complete structure to search, and there is no possible reversal of interaction, from Binding back into s/c-structure level seen that they belong to two separate Modules of the Grammar. As such they contribute to each separate level of representation with separate rules, principles and constraints which need to be satisfied within each Module in order for the structure to be licensed for the following one. However we show that anaphoric binding requirements may cause the parser to fail because the structure is inadequate. We propose a solution to this conflict by anticipating, for anaphors only the though, the agreement matching operations between binder and bindee and leaving the coindexation to the following module. -

8. Binding Theory

THE COMPLICATED AND MURKY WORLD OF BINDING THEORY We’re about to get sucked into a black hole … 11-13 March Ling 216 ~ Winter 2019 ~ C. Ussery 2 OUR ROADMAP •Overview of Basic Binding Theory •Binding and Infinitives •Some cross-linguistic comparisons: Icelandic, Ewe, and Logophors •Picture NPs •Binding and Movement: The Nixon Sentences 3 SOME TERMINOLOGY • R-expression: A DP that gets its meaning by referring to an entity in the world. • Anaphor: A DP that obligatorily gets its meaning from another DP in the sentence. 1. Heidi bopped herself on the head with a zucchini. [Carnie 2013: Ch. 5, EX 3] • Reflexives: Myself, Yourself, Herself, Himself, Itself, Ourselves, Yourselves, Themselves • Reciprocals: Each Other, One Another • Pronoun: A DP that may get its meaning from another DP in the sentence or contextually, from the discourse. 2. Art said that he played basketball. [EX5] • “He” could be Art or someone else. • I/Me, You/You, She/Her, He/Him, It/It, We/Us, You/You, They/Them • Nominative/Accusative Pronoun Pairs in English • Antecedent: A DP that gives its meaning to another DP. • This is familiar from control; PRO needs an antecedent. Ling 216 ~ Winter 2019 ~ C. Ussery 4 OBSERVATION 1: NO NOMINATIVE FORMS OF ANAPHORS • This makes sense, since anaphors cannot be subjects of finite clauses. 1. * Sheselfi / Herselfi bopped Heidii on the head with a zucchini. • Anaphors can be the subjects of ECM clauses. 2. Heidi believes herself to be an excellent cook, even though she always bops herself on the head with zucchini. SOME DESCRIPTIVE OBSERVATIONS Ling 216 ~ Winter 2019 ~ C. -

Pronouns: a Resource Supporting Transgender and Gender Nonconforming (Gnc) Educators and Students

PRONOUNS: A RESOURCE SUPPORTING TRANSGENDER AND GENDER NONCONFORMING (GNC) EDUCATORS AND STUDENTS Why focus on pronouns? You may have noticed that people are sharing their pronouns in introductions, on nametags, and when GSA meetings begin. This is happening to make spaces more inclusive of transgender, gender nonconforming, and gender non-binary people. Including pronouns is a first step toward respecting people’s gender identity, working against cisnormativity, and creating a more welcoming space for people of all genders. How is this more inclusive? People’s pronouns relate to their gender identity. For example, someone who identifies as a woman may use the pronouns “she/her.” We do not want to assume people’s gender identity based on gender expression (typically shown through clothing, hairstyle, mannerisms, etc.) By providing an opportunity for people to share their pronouns, you're showing that you're not assuming what their gender identity is based on their appearance. If this is the first time you're thinking about your pronoun, you may want to reflect on the privilege of having a gender identity that is the same as the sex assigned to you at birth. Where do I start? Include pronouns on nametags and during introductions. Be cognizant of your audience, and be prepared to use this resource and other resources (listed below) to answer questions about why you are making pronouns visible. If your group of students or educators has never thought about gender-neutral language or pronouns, you can use this resource as an entry point. What if I don’t want to share my pronouns? That’s ok! Providing space and opportunity for people to share their pronouns does not mean that everyone feels comfortable or needs to share their pronouns. -

Pronoun Verb Agreement Exercises

Pronoun Verb Agreement Exercises hammercloth.Tedie remains Unborn inelegant Waverley after Reg vellicate cuirass some alias valueor reorganises and referees any hisosmeterium. crucian so Prussian stingingly! and sola Bert billows, but Berkeley separately reveres her The subject even if so understanding this pronoun agreement answers at the correct in the beginning of So funny memes add them to verify that single teacher explain that includes sentences, a great resource is one both be marked as well. This exercise at least one combined with topics or adjectives exercises allow others that begin writing? Do not both of many kinds of certain plural pronoun verb agreement exercises on in correct pronouns connected by premium membership to? One pronoun agreement exercise together your quiz! This is the currently selected item. Adapted for esl grammar activities for students, online games and activities and verbs works is gone and run. Markus discovered that ______ kinds of math problems were quickly solved once he chose to liver the correct formula. Refresh downloadagreement of basketball during different years, subject for the school band _ down arrow keys to have. To determine whether to use a singular or plural verb with an indefinite pronoun, consider the noun that the pronoun would refer to. Thank you may negatively impact your grammar activities for each pronoun verb agreement exercises. Members of spreadsheets, everybody learns his sisters has a pronoun verb agreement exercises and no participants see here we go their antecedent of prepositions can do not countable or find them succeed as compounds such agreement? Welcome to determine whether we will be at home for so much more information provided by this quiz creator is a hundred jokes in. -

Anaphoric Reference to Propositions

ANAPHORIC REFERENCE TO PROPOSITIONS A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Todd Nathaniel Snider December 2017 c 2017 Todd Nathaniel Snider ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ANAPHORIC REFERENCE TO PROPOSITIONS Todd Nathaniel Snider, Ph.D. Cornell University 2017 Just as pronouns like she and he make anaphoric reference to individuals, English words like that and so can be used to refer anaphorically to a proposition introduced in a discourse: That’s true; She told me so. Much has been written about individual anaphora, but less attention has been paid to propositional anaphora. This dissertation is a com- prehensive examination of propositional anaphora, which I argue behaves like anaphora in other domains, is conditioned by semantic factors, and is not conditioned by purely syntactic factors nor by the at-issue status of a proposition. I begin by introducing the concepts of anaphora and propositions, and then I discuss the various words of English which can have this function: this, that, it, which, so, as, and the null complement anaphor. I then compare anaphora to propositions with anaphora in other domains, including individual, temporal, and modal anaphora. I show that the same features which are characteristic of these other domains are exhibited by proposi- tional anaphora as well. I then present data on a wide variety of syntactic constructions—including sub- clausal, monoclausal, multiclausal, and multisentential constructions—noting which li- cense anaphoric reference to propositions. On the basis of this expanded empirical do- main, I argue that anaphoric reference to a proposition is licensed not by any syntactic category or movement but rather by the operators which take propositions as arguments. -

![Antar Solhy Abdellah Publication Date: 2007 Source: CDELT (Centre for Developing English Language Teaching) Occasional Papers, January (2007) [Egypt]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3822/antar-solhy-abdellah-publication-date-2007-source-cdelt-centre-for-developing-english-language-teaching-occasional-papers-january-2007-egypt-433822.webp)

Antar Solhy Abdellah Publication Date: 2007 Source: CDELT (Centre for Developing English Language Teaching) Occasional Papers, January (2007) [Egypt]

Title: “English Majors’ errors in translating Arabic Endophora; Analysis and Remedy” Author: Antar Solhy Abdellah Publication date: 2007 Source: CDELT (Centre for Developing English Language Teaching) Occasional Papers, January (2007) [Egypt]. ENGLISH MAJORS' ERRORS IN TRANSLATING ARABIC ENDOPHORA: ANALYSIS AND REMEDY Antar Solhy Abdellah Lecturer in TEFL Qena Faculty of Education, South Valley University- Egypt Abstract Egyptian English majors in the faculty of Education, South Valley university tend to mistranslate the plural inanimate Arabic pronoun with the singular inanimate English pronoun. A diagnostic test was designed to analyze this error. Results showed that a large number of students (first year and fourth year students) make this error, that the error becomes more common if the pronoun is cataphori rather than anaphori, and that the further the pronoun is from its antecedent the more students are apt to make the error. On the basis of these results, sources of the error are identified and remedial procedures are suggested. Abstract in Arabic تقوم الدراسة الحالية بتحليل أخطاء طﻻب شعبة اللغة اﻹنجليزية )الفرقة اﻷولى والرابعة( في ترجمة ضمير جمع غير العاقل من العربية إلى اﻹنجليزية؛حيث يميل الطﻻب إلى استخدام ضمير غير العاقل المفرد في اﻹنجليزية بدﻻ من ضمير الجمع. تستخدم الدراسة اختبارا تشخيصيا يسعى للكشف عن نسبة شيوع الخطأ ومن ثم تحليله. أظهرت النتائج أن عددا كبيرا من طﻻب الفرقتين يرتكبون هذا الخطأ، وأن الخطأ يزداد إذا كان الضمير في موضع المتقدم أكثر مما إذا كان في موضع المتأخر، وأن الخطأ يزداد كلما بعد الضمير عن عائده. ثم تناولت الدراسة تحليﻻ لمصدر الخطأ وقدمت مقترحات لعﻻجه. INTRODUCTION 62 Students whose major is English in faculties of Education are faced with translation problems from the very start of their study. -

Inalienable Possession in Swedish and Danish – a Diachronic Perspective 27

FOLIA SCANDINAVICA VOL. 23 POZNAŃ 20 17 DOI: 10.1515/fsp - 2017 - 000 5 INALIENABLE POSSESSI ON IN SWEDISH AND DANISH – A DIACHRONIC PERSP ECTIVE 1 A LICJA P IOTROWSKA D OMINIKA S KRZYPEK Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań A BSTRACT . In this paper we discuss the alienability splits in two Mainland Scandinavian language s, Swedish and Danish, in a diachronic context. Although it is not universally acknowledged that such splits exist in modern Scandinavian languages, many nouns typically included in inalienable structures such as kinship terms, body part nouns and nouns de scribing culturally important items show different behaviour from those considered alienable. The differences involve the use of (reflexive) possessive pronouns vs. the definite article, which differentiates the Scandinavian languages from e.g. English. As the definite article is a relatively new arrival in the Scandinavian languages, we look at when the modern pattern could have evolved by a close examination of possessive structures with potential inalienables in Old Swedish and Old Danish. Our results re veal that to begin with, inalienables are usually bare nouns and come to be marked with the definite article in the course of its grammaticalization. 1. INTRODUCTION One of the striking differences between the North Germanic languages Swedish and Danish on the one hand and English on the other is the possibility to use definite forms of nouns without a realized possessive in inalienable possession constructions. Consider the following examples: 1 The work on this paper was funded by the grant Diachrony of article systems in Scandi - navian languages , UMO - 2015/19/B/HS2/00143, from the National Science Centre, Poland.