00 Tribal Identity Rep Final

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IPPF: India: Rajasthan Renewable Energy Transmission Investment

Indigenous Peoples Planning Framework (IPPF) Document Stage: Draft for Consultation Project Number: June 2012 India: Rajasthan Renewable Energy Transmission Investment Program Rajasthan Rajya Vidyut Prasaran Nigam Limited (RRVPNL) Government of Rajasthan The Indigenous Peoples Planning Framework is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB‘s Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Page 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ACRONYMS ............................................................................................................. A. INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………………………….. B. OBJECTIVES AND POLICY FRAMEWORK…………………………………………… C. IDENTIFICATION OF AFFECTED INDIGENOUS PEOPLES ……………………….. D. SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT AND STEPS FOR FORMULATING AN IPP …... 1. Preliminary Screening………………………………………………….…..…….. 2. Social Impact Assessment………………………………………………..….….. 3. Benefits Sharing and Mitigation Measures………………………..…..………. 4. Indigenous Peoples Plan…………………………………………………..…..…. E. CONSULTATION, PARTICIPATION AND DISCLOSURE …………………….……... F. GRIEVANCE REDRESS MECHANISM…………………………………………….…….. G. INSTITUTIONAL AND IMPLEMENTATION ARRANGEMENTS……………….……… H. MONITORING AND REPORTING ARRANGEMENTS ………………………….……… I. BUDGET AND FINANCING ………………………………………………………….……. ANNEXURE Annexure-1 LEGAL FRAMEWORK …………………………………………………………….. Annexure-2 INDIGENOUS PEOPLES IMPACT SCREENING CHECKLIST………..…….. Annexure-3 OUTLINE OF AN INDIGENOUS PEOPLES PLAN ….………………………… Page 2 List of Acronyms -

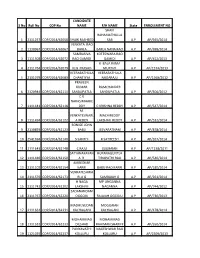

S No Roll No COP No CANDIDATE NAME F/H NAME State

CANDIDATE S No Roll No COP No NAME F/H NAME State ENROLLMENT NO SHAIK RAHAMATHULLA 1 2111257 COP/2014/62058 SHAIK RASHEED SAB A.P AP/945/2014 VENKATA RAO 2 1130967 COP/2014/62067 BARLA BARLA NANA RAO A.P AP/698/2014 SAMBASIVA KOTESWARA RAO 3 1111308 COP/2014/62072 RAO GAMIDI GAMIDI A.P AP/452/2013 K BALA RAMA 4 2111764 COP/2014/62079 KLN PRASAD MURTHY A.P AP/1574/2013 VEERABATHULA VEERABATHULA 5 2131079 COP/2014/62083 CHANTIYYA NAGARAJU A.P AP/1568/2012 PRAVEEN KUMAR RAMCHANDER 6 2120944 COP/2014/62111 SANDUPATLA SANDUPATLA A.P AP/306/2012 C V NARASIMHARE 7 1111441 COP/2014/62118 DDY C KRISHNA REDDY A.P AP/547/2014 M. VENKATESWARL MACHIREDDY 8 1111494 COP/2014/62122 A REDDY LAKSHMI REDDY A.P AP/532/2014 BONIGE JOHN 9 2130893 COP/2014/62123 BABU JEEVARATNAM A.P AP/878/2014 10 2541694 COP/2014/62140 S SANTHI R SATHEESH A.P AP/267/2014 11 2111643 COP/2014/62148 C RAJU SUGRAIAH A.P AP/1238/2011 SATYANARAYAN RUPANAGUNTLA 12 1111480 COP/2014/62150 A R. TIRUPATHI RAO A.P AP/540/2014 AMBEDKAR 13 2131102 COP/2014/62154 KARRI BABU RAO KARRI A.P AP/180/2014 VENKATESHWA 14 2111570 COP/2014/62173 RLU G SAMBAIAH G A.P AP/261/2014 H NAGA MP LINGANNA 15 2111742 COP/2014/62202 LAKSHMI NAGANNA A.P AP/744/2012 SADANANDAM 16 2111767 COP/2014/62220 OGGOJU RAJAIAH OGGOJU A.P AP/736/2013 MADHUSUDAN MOGILAIAH 17 2111661 COP/2014/62231 KACHAGANI KACHAGANI A.P AP/478/2014 MOHAMMAD MOHAMMAD 18 1111532 COP/2014/62233 DILSHAD RAHIMAN SHARIFF A.P AP/550/2014 PUNYAVATHI NAGESHWAR RAO 19 1121035 COP/2014/62237 KOLLURU KOLLURU A.P AP/2309/2013 G SATHAKOTI GEESALA 20 2131021 COP/2014/62257 SRINIVAS NAGABHUSHANAM A.P AP/1734/2011 GANTLA GANTLA SADHU 21 1131067 COP/2014/62258 SANYASI RAO RAO A.P AP/1802/2013 KOLICHALAM NAVEEN KOLICHALAM 22 1111688 COP/2014/62265 KUMAR BRAHMAIAH A.P AP/1908/2010 SRINIVASA RAO SANKARA RAO 23 2131012 COP/2014/62269 KOKKILIGADDA KOKKILIGADDA A.P AP/793/2013 24 2120971 COP/2014/62275 MADHU PILLI MAISAIAH PILLI A.P AP/108/2012 SWARUPARANI 25 2131014 COP/2014/62295 GANJI GANJIABRAHAM A.P AP/137/2014 26 2111507 COP/2014/62298 M RAVI KUMAR M LAXMAIAH A.P AP/177/2012 K. -

Tables on Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes, Part V-A, Vol-V

PRO. 18 (N) (Ordy) --~92f---- CENSUS O}-' INDIA 1961 VOLUME V GUJARAT PART V-A TABLES ON SCHEDULED CASTES AND SCHEDULED TRIBES R. K. TRIVEDI Superintendent of Census Operations, Gujarat PUBLISHED BY THE MANAGER OF PUBLICATIONS, DELHI 1964 PRICE Rs. 6.10 oP. or 14 Sh. 3 d. or $ U. S. 2.20 0 .. z 0", '" o~ Z '" ::::::::::::::::3i=:::::::::=:_------_:°i-'-------------------T~ uJ ~ :2 I I I .,0 ..rtJ . I I I I . ..,N I 0-t,... 0 <I °...'" C/) oZ C/) ?!: o - UJ z 0-t 0", '" '" Printed by Mafatlal Z. Gandhi at Nayan Printing Press, Ahmedabad-} CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 LIST OF PUBLICATIONS CENTRAl- GoVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS Census of India, 1961 Volume V-:Gujatat is being published in the following parts: I-A General Eep8rt 1-·B Report on Vital Statistics and Fertility Survey I~C Subsidiary Tables II-A General Population Tables n-B(l) General Economic Tables (Table B-1 to B-lV-C) II-B(2) General Economic Tables (Table B-V to B-IX) Il-C Cultural and Migration Tables IU Household Economic Tables (Tables B-X to B-XVII) IV-A Report on Housing and Establishments IV-B Housing and Establishment Tables V-A Tables on Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes V-B Ethnographic Notes on Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (including reprints) VI Village Survey Monographs (25 Monographs) VII-A Seleted Crafts of Gujarat VII-B Fairs and Fest,ivals VIlI-A Administration Report-EnumeratiOn) Not for Sale VllI-B Administration Report-Tabulation IX Atlas Volume X Special Report on Cities STATE GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS 17 District Census Handbooks in English 17 District Census Handbooks in Gujarati CO NTF;N'TS Table Pages Note 1- 6 SCT-I PART-A Industrial Classification of Persons at Work and Non·workers by Sex for Scheduled Castes . -

A Curriculum to Prepare Pastors for Tribal Ministry in India

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Dissertation Projects DMin Graduate Research 2007 A Curriculum To Prepare Pastors for Tribal Ministry in India Calvin N. Joshua Andrews University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dmin Part of the Practical Theology Commons Recommended Citation Joshua, Calvin N., "A Curriculum To Prepare Pastors for Tribal Ministry in India" (2007). Dissertation Projects DMin. 612. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dmin/612 This Project Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertation Projects DMin by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT A CURRICULUM TO PREPARE PASTORS FOR TRIBAL MINISTRY IN INDIA by Calvin N. Joshua Adviser: Bruce L. Bauer ABSTRACT OF GRADUATE STUDENT RESEARCH Dissertation Andrews University Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary Title: A CURRICULUM TO PREPARE PASTORS FOR TRIBAL MINISTRY IN INDIA Name of researcher: Calvin N. Joshua Name and degree of faculty adviser: Bruce L. Bauer, DMiss. Date Completed: September 2007 Problem The dissertation project establishes the existence of nearly one hundred million tribal people who are forgotten but continue to live in human isolation from the main stream of Indian society. They have their own culture and history. How can the Adventist Church make a difference in reaching them? There is a need for trained pastors in tribal ministry who are culture sensitive and knowledgeable in missiological perspectives. Method Through historical, cultural, religious, and political analysis, tribal peoples and their challenges are identified. -

The Effect of Development on the Culture of the Adivasis" (2009)

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CMC Senior Theses CMC Student Scholarship 2009 Advancement of the Adivasis: The ffecE t of Development on the Culture of the Adivasis Jantrania Akta Claremont McKenna College Recommended Citation Akta, Jantrania, "Advancement of the Adivasis: The Effect of Development on the Culture of the Adivasis" (2009). CMC Senior Theses. Paper 227. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/227 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you by Scholarship@Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in this collection by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CLAREMONT McKENNA COLLEGE ADVANCEMENT OF THE ADIVASIS: THE EFFECT OF DEVELOPMENT ON THE CULTURE OF THE ADIVASIS SUBMITTED TO PROFESSOR WILLIAM ASCHER AND DEAN GREGORY HESS BY AKTA JANTRANIA FOR SENIOR THESIS FALL 2008 / SPRING 2009 ARPIL 27, 2009 Table of Contents List of Figures and Tables....................................................................................... ii Acknowledgements ................................................................................................ iii Chapter 1: Introduction ....................................................................................... 1 Objectives of Study ............................................................................................. 4 Diversity of the Adivasis ..................................................................................... 5 Government Policy Toward the Adivasis .......................................................... -

(Amendment) Act, 1976

~ ~o i'T-(i'T)-n REGISTERED No. D..(D).71 ':imcT~~ •••••• '0 t:1t~~~<1~etkof &india · ~"lttl~ai, ~-. ...- .. ~.'" EXTRAORDINARY ~ II-aq 1 PART ll-Section 1 ~ d )\q,,~t,- .PUBLISHE:Q BY AUTHORITY do 151] itt f~T, m1l<fR, fuaq~ 20, 1976/m'i{ 29, 1898 No. ISI] NEWDELID, MONDAY, SEPTEMBER 20, I976/BHADRA 29, I898 ~ ~ iT '~ ~ ~ ;if ri i' ~ 'r.t; ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ iT rnf ;m ~lj l Separate paging is given to this Part in order that it may be ftled as a separate compilat.on I MINISTRY OF LAW, JUSTICE AND COMPANY AFFAIRS (Legislative Department) New Delhi, the 20th Septembe1', 1976/Bhadra 29, 1898 (Saka) The following Act of Parliament received the assent of the President on the 18th September, 1976,and is hereby published for general informa tion:- THE SCHEDULED CASTES AND SCHEDULED TRIBES ORDERS (AMENDMENT) ACT, 1976 No· 100 OF 1976 [18th September, 1976] An Act to provide for the inclusion in, and the exclusion from, the lists of Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes, of certain castes and tribes, for the re-adjustment of representation of parliamentry and assembly constituencies in so far as such re adjustment is necessiatated by such inclusion of exclusion and for matters connected therewith. BE it enacted by Parliament in the Twenty-seventh Year of the R.epublic of India as follows:- 1. (1) This Act may be called the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Short title and Tribes Orders (Amendment) Act, 1976. Com (2) It shall come into force on such date as the Central Government mence ment. may, by notification in the Official Gazette, appoint. -

CROCS of CHAROTAR Status, Distribution and Conservation of Mugger Crocodiles in Charotar, Gujarat, India

CROCS OF CHAROTAR Status, Distribution and Conservation of Mugger Crocodiles in Charotar, Gujarat, India THE DULEEP MATTHAI NATURE CONSERVATION TRUST Voluntary Nature Conservancy (VNC) acknowledges the support to this publication given by Ruff ord Small Grant Foundation, Duleep Matthai Nature Conservation Trust and Idea Wild. Published by Voluntary Nature Conservancy 101-Radha Darshan, Behind Union Bank, Vallabh Vidyanagar-388120, Gujarat, India ([email protected]) Designed by Niyati Patel & Anirudh Vasava Credits Report lead: Anirudh Vasava, Dhaval Patel, Raju Vyas Field work: Vishal Mistry, Mehul Patel, Kaushal Patel, Anirudh Vasava Data analysis: Anirudh Vasava, Niyati Patel Report Preparation: Anirudh Vasava Administrative support: Dhaval Patel Cover Photo: Mehul B. Patel Suggested Citation: Vasava A., Patel D., Vyas R., Mis- try V. & Patel M. (2015) Crocs of Charotar: Status, distri- bution and conservation of Mugger crocodiles in Charotar region , Gujarat, India. Voluntary Nature Conservancy, Vallabh Vidyanagar, India. Reproduction and dissemination of material in this pub- lication for educational or any non-commercial purpos- es are authorized without any prior written permission from the publisher provided the source is fully acknowl- edged and appropriate credit given. Reproduction of material in this information product for or other com- mercial purposes is prohibited without written permis- sion of the Publisher. Applications for such permission should be addressed to the Managing Trustee, Voluntary Nature Conservancy or by -

Indian Tribal Ornaments; a Hidden Treasure

IOSR Journal of Environmental Science, Toxicology and Food Technology (IOSR-JESTFT) e-ISSN: 2319-2402,p- ISSN: 2319-2399.Volume 10, Issue 3 Ver. II (Mar. 2016), PP 01-16 www.iosrjournals.org Indian Tribal Ornaments; a Hidden Treasure Dr. Jyoti Dwivedi Department of Environmental Biology A.P.S. University Rewa (M.P.) 486001India Abstract: In early India, people handcrafted jewellery out of natural materials found in abundance all over the country. Seeds, feathers, leaves, berries, fruits, flowers, animal bones, claws and teeth; everything from nature was affectionately gathered and artistically transformed into fine body jewellery. Even today such jewellery is used by the different tribal societies in India. It appears that both men and women of that time wore jewellery made of gold, silver, copper, ivory and precious and semi-precious stones.Jewelry made by India's tribes is attractive in its rustic and earthy way. Using materials available in the local area, it is crafted with the help of primitive tools. The appeal of tribal jewelry lies in its chunky, unrefined appearance. Tribal Jewelry is made by indigenous tribal artisans using local materials to create objects of adornment that contain significant cultural meaning for the wearer. Keywords: Tribal ornaments, Tribal culture, Tribal population , Adornment, Amulets, Practical and Functional uses. I. Introduction Tribal Jewelry is primarily intended to be worn as a form of beautiful adornment also acknowledged as a repository for wealth since antiquity. The tribal people are a heritage to the Indian land. Each tribe has kept its unique style of jewelry intact even now. The original format of jewelry design has been preserved by ethnic tribal. -

Tribal Population Planning Framework for Gujarat Rural Roads (Mmgsy) Project

GUJARAT STATE RURAL ROAD DEVELOPMENT AGENCY (GSRRDA) Roads and Buildings Department Government of Gujarat TRIBAL POPULATION PLANNING FRAMEWORK FOR GUJARAT RURAL ROADS (MMGSY) PROJECT Environmental and Social Management Framework for MMGSY (Under AIIB Loan Assistance) May 2017 LEA Associates South Asia Pvt. Ltd., India Gujarat State Rural Road Development Agency Tribal Population (GSRRDA) Planning Framework for MMGSY TABLE OF CONTENTS TRIBAL POPULATION PLANNING FRAMEWORK ............................................................... 1 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................. 1 2 PROJECT BACKGROUND ................................................................................................ 2 3 NEED FOR TRIBAL POPULATION PLANNING FRAMEWORK .............................. 4 4 OBJECTIVES AND PROVISIONS OF TPPF ................................................................... 5 5 DEMOGRAPHIC PROFILE OF SCHEDULED TRIBES IN GUJARAT ..................... 6 5.1 Notified Tribes in Gujarat ............................................................................................ 6 5.2 Primitive Tribal Groups ............................................................................................... 6 6 LEGAL AND POLICY FRAMEWORK ............................................................................ 7 7 POTENTIAL IMPACTS ...................................................................................................... 9 8 LAND SECURING AND -

The Bombay Reorganisation Act, 1960

THE BOMBAY REORGANISATION ACT, 1960 ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS PART I PRELIMINARY SECTIONS 1. Short title. 2. Definitions. PART II REORGANISATION OF BOMBAY STATE 3. Formation of Gujarat State. 4. Amendment of the First Schedule to the Constitution 5. Saving powers of State Government. PART III REPRESENTATION IN THE LEGISLATURES The Council of States 6. Amendment of the Fourth Schedule to the Constitution. 7. Allocation of sitting members. 8. Bye-elections to fill vacancies. 9. Term of office. The House of the People 10. Representation in the House of the -People. 11. Delimitation of Parliamentary constituencies. 12. Provision as to sitting members. The Legislative Assemblies 13. Strength of Legislative Assemblies. 14. Delimitation of Assembly constituencies. 15. Allocation of members. 16. Duration of Legislative Assemblies. 17. Speakers and Deputy Speakers. 18. Rules of Procedure, ii Bombay Reorganisation [ACT. 11 SECTIONS 19. Special provisions in relation to Gujarat Legislative Assembly. The Legislative Council 20. Amendment of article 168 of the Constitution. 21. Legislative Council of Maharashtra. 22. Council constituencies. 23. Provision as to certain sitting members. 24. Special provision as to biennial elections. 25. Chaiiinan and Deputy Chairman. Scheduied Castes and Scheduled Tribes 26. Amendment of the Scheduled Castes Order. 97. Amendment of the Scheduled Tribes Order. PART IV HIGH COURTS 28. High Court for Gujarat. 29. Judges of Gujarat High Court. 30. Jurisdiction of Gujarat High Court. l. Power to enrol advocates, etc. 32. Practice and procedure in Gujarat High Court. 33. Custody of seal of Gujarat High Court. 34. Form of writs and other processes. 35. Powers of Judges. 36. Procedure as to appeals to Supreme Court. -

18Bge43c - Human Geography

18BGE43C - HUMAN GEOGRAPHY [Syllabus, UNIT – III: Race and Racial Groups: Grifith Taylor‘s Theory of Human Race - Ethnic groups in India and World - Indian Tribes - Gonds - Bhill - Naga – Santhal.] Races The word race came into usage in English language in the 16th century. It was Thomas de Gobineau who attempted the first classification of human beings on the basis of physical characteristics. NEGROID RACES (African, Hottentots, Melanesians/Papua, ―Negrito‖, Australian Aborigine, Dravidians, Sinhalese) Origin of Negroids:- The word „Negro‟ is derived from a latin word known as „Nigor‟ which means Black‟. The main habitat of Negroids is Africa continent and their main habitat is S.Africa that is why this place is also known as Black Africa. Majority of negroids is found in middle and southern Africa which is also termed as black Africa. Features of Negroids:- Skin, eyes and hairs are black in colour Hairs are wooly, curly & frizzly. Jueir hights are found tall to very short PRIMARY NEGROES Forest Negroes:- They are mainly found in southern region of Africa. They are also known as sodani Negroes. They are also found in sahara desert which lies in N & S where there is dense equatorial forest. The maximum clear indication of the negroid race is found in the forest negroes & therefore they are termed as true Negroes. Features of forest Negroes:- Long, Wooly and wavy hairs and are black in colour. Their lips are thick. Skin colour varies from chocolaty to dark Brown. Their average height is 162-172 cms. Fewer hairs are found on skin & face. Negrotic or pigmies:- They are mainly found in Congo Basin in Africa. -

1The Constitution (Scheduled Tribes) Order, 1950

171 1THE CONSTITUTION (SCHEDULED TRIBES) ORDER, 1950 C.O. 22 In exercise of the powers conferred by clause (1) of article 342 of the Constitution of India, the President, after consultation with the Governors and Rajpramukhs of the States concerned, is pleased to make the following Order, namely:-- 1. This Order may be called the Constitution (Scheduled Tribes) Order, 1950. 2. The Tribes or tribal communities, or parts of, or groups within, tribes or tribal communities, specified in 2[Parts I to 3[XXII] of the Schedule to this Order shall, in relation to the States to which those Parts respectively relate, be deemed to be Scheduled Tribes so far as regards members thereof residents in the localities specified in relation to them respectively in those Parts of that Schedule. 4[3. Any reference in this Order to State or to a district or other territorial division thereof shall be construed as a reference to the State, district or other territorial division as constituted on the 1st day of May, 1976.] __________________________________________________________________________________________________ _ 1. Published with the Ministry of Law Notifn. No. S.R.O. 510, dated the 6th September, 1950, Gazette of India, Extraordinary, 1950, Part II, Section 3, page 597. 2. Subs. by the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes Lists (Modification) Order, 1956. 3. The figure ‘XVIII’ has been successively subs. by Act 18 of 1987, s. 19 and Second Sch (w.e.f. 30.5.87) by Act 28 of 2000, s. 20 and Fourth Sch. (w.e.f. 1-11-2000) by Act 29 of 2000, s.