The Effect of Development on the Culture of the Adivasis" (2009)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

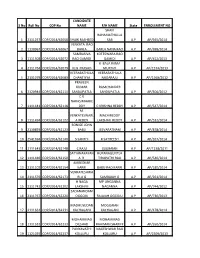

S No Roll No COP No CANDIDATE NAME F/H NAME State

CANDIDATE S No Roll No COP No NAME F/H NAME State ENROLLMENT NO SHAIK RAHAMATHULLA 1 2111257 COP/2014/62058 SHAIK RASHEED SAB A.P AP/945/2014 VENKATA RAO 2 1130967 COP/2014/62067 BARLA BARLA NANA RAO A.P AP/698/2014 SAMBASIVA KOTESWARA RAO 3 1111308 COP/2014/62072 RAO GAMIDI GAMIDI A.P AP/452/2013 K BALA RAMA 4 2111764 COP/2014/62079 KLN PRASAD MURTHY A.P AP/1574/2013 VEERABATHULA VEERABATHULA 5 2131079 COP/2014/62083 CHANTIYYA NAGARAJU A.P AP/1568/2012 PRAVEEN KUMAR RAMCHANDER 6 2120944 COP/2014/62111 SANDUPATLA SANDUPATLA A.P AP/306/2012 C V NARASIMHARE 7 1111441 COP/2014/62118 DDY C KRISHNA REDDY A.P AP/547/2014 M. VENKATESWARL MACHIREDDY 8 1111494 COP/2014/62122 A REDDY LAKSHMI REDDY A.P AP/532/2014 BONIGE JOHN 9 2130893 COP/2014/62123 BABU JEEVARATNAM A.P AP/878/2014 10 2541694 COP/2014/62140 S SANTHI R SATHEESH A.P AP/267/2014 11 2111643 COP/2014/62148 C RAJU SUGRAIAH A.P AP/1238/2011 SATYANARAYAN RUPANAGUNTLA 12 1111480 COP/2014/62150 A R. TIRUPATHI RAO A.P AP/540/2014 AMBEDKAR 13 2131102 COP/2014/62154 KARRI BABU RAO KARRI A.P AP/180/2014 VENKATESHWA 14 2111570 COP/2014/62173 RLU G SAMBAIAH G A.P AP/261/2014 H NAGA MP LINGANNA 15 2111742 COP/2014/62202 LAKSHMI NAGANNA A.P AP/744/2012 SADANANDAM 16 2111767 COP/2014/62220 OGGOJU RAJAIAH OGGOJU A.P AP/736/2013 MADHUSUDAN MOGILAIAH 17 2111661 COP/2014/62231 KACHAGANI KACHAGANI A.P AP/478/2014 MOHAMMAD MOHAMMAD 18 1111532 COP/2014/62233 DILSHAD RAHIMAN SHARIFF A.P AP/550/2014 PUNYAVATHI NAGESHWAR RAO 19 1121035 COP/2014/62237 KOLLURU KOLLURU A.P AP/2309/2013 G SATHAKOTI GEESALA 20 2131021 COP/2014/62257 SRINIVAS NAGABHUSHANAM A.P AP/1734/2011 GANTLA GANTLA SADHU 21 1131067 COP/2014/62258 SANYASI RAO RAO A.P AP/1802/2013 KOLICHALAM NAVEEN KOLICHALAM 22 1111688 COP/2014/62265 KUMAR BRAHMAIAH A.P AP/1908/2010 SRINIVASA RAO SANKARA RAO 23 2131012 COP/2014/62269 KOKKILIGADDA KOKKILIGADDA A.P AP/793/2013 24 2120971 COP/2014/62275 MADHU PILLI MAISAIAH PILLI A.P AP/108/2012 SWARUPARANI 25 2131014 COP/2014/62295 GANJI GANJIABRAHAM A.P AP/137/2014 26 2111507 COP/2014/62298 M RAVI KUMAR M LAXMAIAH A.P AP/177/2012 K. -

Adivasis of India ASIS of INDIA the ADIV • 98/1 T TIONAL REPOR an MRG INTERNA

Minority Rights Group International R E P O R T The Adivasis of India ASIS OF INDIA THE ADIV • 98/1 T TIONAL REPOR AN MRG INTERNA BY RATNAKER BHENGRA, C.R. BIJOY and SHIMREICHON LUITHUI THE ADIVASIS OF INDIA © Minority Rights Group 1998. Acknowledgements All rights reserved. Minority Rights Group International gratefully acknowl- Material from this publication may be reproduced for teaching or other non- edges the support of the Danish Ministry of Foreign commercial purposes. No part of it may be reproduced in any form for com- Affairs (Danida), Hivos, the Irish Foreign Ministry (Irish mercial purposes without the prior express permission of the copyright holders. Aid) and of all the organizations and individuals who gave For further information please contact MRG. financial and other assistance for this Report. A CIP catalogue record for this publication is available from the British Library. ISBN 1 897693 32 X This Report has been commissioned and is published by ISSN 0305 6252 MRG as a contribution to public understanding of the Published January 1999 issue which forms its subject. The text and views of the Typeset by Texture. authors do not necessarily represent, in every detail and Printed in the UK on bleach-free paper. in all its aspects, the collective view of MRG. THE AUTHORS RATNAKER BHENGRA M. Phil. is an advocate and SHIMREICHON LUITHUI has been an active member consultant engaged in indigenous struggles, particularly of the Naga Peoples’ Movement for Human Rights in Jharkhand. He is convenor of the Jharkhandis Organi- (NPMHR). She has worked on indigenous peoples’ issues sation for Human Rights (JOHAR), Ranchi unit and co- within The Other Media (an organization of grassroots- founder member of the Delhi Domestic Working based mass movements, academics and media of India), Women Forum. -

The Impact of Cultural Diversity and Globalization in Developing a Santal Peer Culture in Middle India

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Diposit Digital de Documents de la UAB The impact of cultural diversity and globalization in developing a Santal peer culture in Middle India Marine Carrin Tambslyche Centre d‟Anthropologie, LISST, Toulouse, France. [email protected] EMIGRA Working Papers núm. 46 ISSN 2013-3804 Los contenidos de este texto están bajo una licencia Creative Commons Marine Carrin Tambslyche Resumen/ Abstract How it is to be an adolescent among the Santals, in a world still shaped by tradition but where local knowledge has been pervaded by political awareness and modernity.? The Santals, who number more than five millions, consider themselves as a «tribal» people speaking a different language (austro- asiatic) and sharing a way of life which implies values different from those of the Hindus. A central question , here, concerns the transmission of knowledge. In a tribal context, traditional knowledge is to a large extent endogenously determined. Differences in knowledge are no longer controlled by the elders, but still provide much of the momentum for social interaction. Since the colonial period schooling has been important but it has not succeeded to bring an equal opportunity of chances for all children. In brief, I will analyze how the traditional model of transmission is influenced by exogenous factors, such as schooling or politics, and events which allow children to emerge as new agents, developing a peer culture (W. Corsaro & D. Eder 1990). In the context of tribal India, where educational rights are granted by the Constitution, schooling often implies the dominance of Hindu culture on tribal children who feel stigmatized. -

“Empowerment of Dalits and Adivasis: Role of Education in the Emerging

- 1 - CASI WORKING PAPER SERIES Number 09-04 11/2009 EMPOWERMENT OF DALITS AND ADIVASIS ROLE OF EDUCATION IN THE EMERGING ECONOMY NARENDRA JADHAV Member, Planning Commission, Government of India A Nand & Jeet Khemka Distinguished Lecture Wednesday, December 3, 2008 CENTER FOR THE ADVANCED STUDY OF INDIA University of Pennsylvania 3600 Market Street, Suite 560 Philadelphia, PA 19104 http://casi.ssc.upenn.edu/index.htm © Copyright 2009 Narendra Jadhav and CASI CCENTERENTER FFOROR TTHEHE AADVANCEDDVANCED SSTUDYTUDY OOFF IINDIANDIA © Copyright 2009 Narendra Jadhav and the Center for the Advanced Study of India - 2 - December 3, 2008 Dr. Ronald Daniels, Dr. Ram Rawat, Dr. Devesh Kapur, Ladies and Gentlemen, Please accept my apologies for being late. As was mentioned, I made a dramatic entry. I came straightaway from the flight. I’m not even out of the jet lag, and I’m not able to even hear very clearly, but Devesh said that everybody is waiting and you must deliver, and so I am here…so if I’m going to be a little more incoherent than what I normally am, you will please forgive me. Well, ladies and gentlemen, I feel greatly honored to have been invited to deliver this inaugural keynote lecture in the Nand & Jeet Khemka Distinguished Lecture series for this international conference on India’s Dalits. I am indeed grateful to my friend Professor Devesh Kapur, Director of CASI, and his colleagues at the University of Pennsylvania for providing me this opportunity to participate in this conference on a theme that has been very close to my heart. -

Colonial Representations of Adivasi Pasts of Jharkhand, India: the Archives and Beyond

https://books.openedition.org/pressesinalco/23721?lang=en#text Colonial Representations of Adivasi Pasts of Jharkhand, India: the Archives and Beyond Représentations coloniales des passés des Adivasi du Jarkhand, Inde : les archives et au-delà Sanjukta Das Gupta p. 353-362 Abstract Index Text Bibliography Notes Author Abstract English Français Adivasis are the indigenous people of eastern and central India who were identified as “tribes” under British colonial rule and who today have a constitutional status as “Scheduled Tribese. The notion of tribe, despite its evolutionist character, has been internalized to a large extent by the indigenous people themselves and has had a considerable role in shaping community identities. Colonial studies, moreover, were the first systematic investigations into these marginalized and subordinated communities and form an important primary source in historical research on Adivasis. It would be worthwhile, therefore, to identify the main currents of thought that informed and which in turn were reflected in such works. In conclusion, we may argue that rather than a monolithic view, colonial writing encompassed various genres that, despite apparent commonalities, reveal wide divergences over time and space in the manner in which India’s Adivasis were conceptualized and represented. Index terms Mots clés : Asie du Sud, Inde, Jharkhand, XIXe-XXe siècles, Adivasi, colonialisme britannique, Scheduled Tribe Keywords : South Asia, India, 19th-20th centuries, Jharkhand, Adivasi, Bengal, British colonialism, Scheduled Tribe Full text Introduction 1The term “Adivasi” refers to the indigenous people of eastern and central India who are recognized as “Scheduled Tribes” by the Indian Constitution. The notion of “tribe” – introduced in India during colonial times – with its implication of backwardness, geographical isolation, simple technology and racial connotations is problematic, and in recent years it is increasingly replaced, both in academic and popular usage, by adivasi. -

Overview of the Munda Languages

chapter 5 Overview of the Munda Languages Gregory D.S. Anderson 1 Introduction The Munda languages are a group of Austroasiatic languages spoken across portions of central and eastern India by perhaps as many as ten million people total. The Munda peoples are generally believed to represent autochthonous populations over much of their current areas of inhabitation. This is codified in one of the common terms used locally to describe them, adivasi or ‘aboriginal’. Approximate Distribution of N E P A Munda languages L Mundari UTTAR PRADESH Santali INDIA B BIHAR A N Agariya G L Korwa D A HAN Koda JHARK D MADHYA Santali E Agariya Koraku Asuri Turi S PRADESH 5 H KorwaAsuri 4 2 WEST 1 3 2 3 Santali1 BENGAL 5 4 Bhumij 1 5 2 3 Kharia 3 1 Korku H R A G Juang Mahali S 1. Birhor HARASHTRA I MA T ORISSA 2. Ho T A Gorum 3. Kharia H H Remo 4. Mundari C Sora 5. Turi ANDHRA Gutob PRADESH Gta 0 Miles 150 INDIAN OCEAN 0 Km 150 Map 5.1 Location of the Munda languages in India. © koninklijke brill nv, leiden, ���5 | doi ��.��63/9789004�8357�_006 overview of the munda languages 365 Originally, Munda-speaking peoples probably extended over a somewhat larger area before being marginalized into the relatively remote hill country and (formerly) forested areas primarily in the states of Odisha and Jharkhand; significant Munda-speaking groups are also to be found in Madhya Pradesh, and throughout remote areas of Chhattisgarh, West Bengal, Uttar Pradesh, Andhra Pradesh, and Maharashtra, and through migration to virtually all areas of India, especially in tea-producing regions like Assam. -

Rescuing the Identity of the Adivasis from Their Invisibility. the Encounter Between Jesuits and the Indigenous Peoples of India

Rescuing the Identity of the Adivasis from their Invisibility. The Encounter between Jesuits and the Indigenous Peoples of India Presented by: Carmina Peñarrocha Giménez Supervised by: Dr. Rosana Peris Pichastor Dr. Daniel Pinazo Calatayud PhD Dissertation Doctoral Programme 14003 Castellón de la Plana, May 2017 Development Cooperation Cover Design. Warli Tree of Life [image online] Available at: https://es.pinterest.com/SANOOSMOM/warli-painting [Accessed 1 January 2017] Rescuing the Identity of the Adivasis from their Invisibility. The Encounter between Jesuits and the Indigenous Peoples of India Doctoral Programme 14003 Thesis Dissertation Development Cooperation Presented by: Carmina Peñarrocha Giménez Supervised by: Dr. Rosa Ana Peris Pichastor Dr. Daniel Pinazo Calatayud ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Department of Developmental, Educational and Social Psychology and Methodology Interuniversity Institute of Local Development (IIDL/UJI) Castellón de la Plana, May 2017 Rescuing the Identity of the Adivasis from their Invisibility. The Encounter between Jesuits and the Indigenous Peoples of India 2 Rescuing the Identity of the Adivasis from their Invisibility. The Encounter between Jesuits and the Indigenous Peoples of India The village spirits of the village, the house spirit of the house, our elders, our foreparents, our ancestors, the path you made, the road you showed, we follow after you, we emulate your example. We invite you, we call upon you. You sit with us, you talk with us. A cup of rice beer, a plate of mixed gruel. You drink with us, you eat with us. (prayer word used by the tribal priests) 3 Rescuing the Identity of the Adivasis from their Invisibility. The Encounter between Jesuits and the Indigenous Peoples of India 4 Rescuing the Identity of the Adivasis from their Invisibility. -

Socio -Cultural Changes of Tribes and Their Impacts on Environment With

G.J.I.S.S.,Vol.4(3):148-156 (May-June, 2015) ISSN: 2319-8834 Socio -Cultural Changes of Tribes and Their Impacts on Environment with Special Reference to Santhal in West Bengal Subrata Guha & Md Ismail** **Department of Geography, Aliah University, Kolkata, 700014 Abstract A tribe is a group of people living under primitive condition and still not popularly known to more modern culture. There are numbers of tribes living all over India as well as various parts in the World. More than 55% of the total tribal population of India are living in central India like Bihar, West Bengal, Orissa, and Madhya Pradesh and remaining tribal population is concentrated in the Himalayan belt, Western India, the Dravidian region and Andaman, Nicobar and Lakshadweep islands. According to D.N Majumdar, tribes as social group with popular association endogamous with not any particular of functions governed by tribal ruler or otherwise, united in language or dialect recognizing social distance with other tribes or castes. Out of them, Santhal is an important tribe which contributes more than 50% of the Indian tribal population. The paper tries to explain heartening situation of Indian tribes with reference to Santhal communities in Birbhum district and also finds out various cultural as well as food habits, religious practices, social system like marriage and various types of awareness. Social change is one of the important issues which can determined the level of development and change in the pattern of life style. L.M Lewis believes that tribal societies are small in scale are restricted in the spatial and temporal range of their social, legal and political relations and possess a morality, a religion and world view of corresponding dimensions. -

CROCS of CHAROTAR Status, Distribution and Conservation of Mugger Crocodiles in Charotar, Gujarat, India

CROCS OF CHAROTAR Status, Distribution and Conservation of Mugger Crocodiles in Charotar, Gujarat, India THE DULEEP MATTHAI NATURE CONSERVATION TRUST Voluntary Nature Conservancy (VNC) acknowledges the support to this publication given by Ruff ord Small Grant Foundation, Duleep Matthai Nature Conservation Trust and Idea Wild. Published by Voluntary Nature Conservancy 101-Radha Darshan, Behind Union Bank, Vallabh Vidyanagar-388120, Gujarat, India ([email protected]) Designed by Niyati Patel & Anirudh Vasava Credits Report lead: Anirudh Vasava, Dhaval Patel, Raju Vyas Field work: Vishal Mistry, Mehul Patel, Kaushal Patel, Anirudh Vasava Data analysis: Anirudh Vasava, Niyati Patel Report Preparation: Anirudh Vasava Administrative support: Dhaval Patel Cover Photo: Mehul B. Patel Suggested Citation: Vasava A., Patel D., Vyas R., Mis- try V. & Patel M. (2015) Crocs of Charotar: Status, distri- bution and conservation of Mugger crocodiles in Charotar region , Gujarat, India. Voluntary Nature Conservancy, Vallabh Vidyanagar, India. Reproduction and dissemination of material in this pub- lication for educational or any non-commercial purpos- es are authorized without any prior written permission from the publisher provided the source is fully acknowl- edged and appropriate credit given. Reproduction of material in this information product for or other com- mercial purposes is prohibited without written permis- sion of the Publisher. Applications for such permission should be addressed to the Managing Trustee, Voluntary Nature Conservancy or by -

M. a Political Science Iind Sem (202) Jharkhand Movement the Word

M. A Political Science IInd sem (202) Jharkhand Movement The word Jharkhand , meaning "forest region," applies to a forested mountainous plateau region in eastern India. The term dates at least to the sixteenth century. In the more extensive claims of the movement, Jharkhand comprises seven districts in Bihar, three in West Bengal, four in Orissa, and two in Madhya Pradesh. Ninety percent of the Scheduled Tribes in Jharkhand live in the Bihar districts. The tribal peoples, who are from two groups, the Chotanagpurs and the Santals, have been the main agitators for the movement. The tribes have been undergoing a variety of socio-political changes particularly for the last two hundred years. Emergence of certain socio-political movements is one of the variant of these factors. Since the beginning of the last century, tribal Indian has been witnessing an upsurge of social movements. These movements have been of different magnitude in their underlying reasons, origination, objectives, organizational activities and outcome. Almost two centuries ago, Mundas took up arms against the local landlords and the British administration. The leader was BinsuManki. The reason of discontent is transfer of Jharkhand to East India Company in 1771. The movement confined to Bundu area of Ranchi district. GOAL: Jharkhand movement repudiated the Nehruvian model of nation building by reinventing regionalism as the basis of state reorganization in India. The modern tribal movement for regional autonomy is a phenomenon after India got independence. Jharkhand movement too is such a phe Jharkhand movement repudiated the Nehruvian model of nation building by reinventing regionalism as the basis of state reorganization in India. -

Fifth Schedule

Land and Governance Under the Fifth Schedule An Overview of the Law Contents Preface iii Foreword iv Introduction 01 Part I: The Fifth Schedule and its Provisions 04 The Fifth Schedule in the Constitutional Design 04 Brief Outline of the Fifth Schedule Provisions 12 What are Scheduled Areas? 14 Criteria for Declaring an Area as a Scheduled Area 15 Role of the Governor 17 Role of the Tribes Advisory Council 22 Part II: The Panchayats (Extension to Scheduled Areas) Act, 1996 23 Essential Ingredients of the Law 24 The Spirit of PESA 25 Definition of a Village 28 Consultation 29 Minor Minerals 32 Minor Forest Produce 35 Minor Water Bodies 38 Prevention of Land Alienation 41 Control over Institutions, Functionaries and Planning 46 Reservations 48 Additional Powers 50 In Summation 52 Part III: Testing the Law Against Reality 57 Land Alienation and Acquisition 57 Forests 63 Environmental Damage and Destruction of Livelihoods 67 Mining 69 Urbanisation in Scheduled Areas 74 Conclusion 77 Appendices 79 Appendix A: Fifth Schedule to the Constitution of India 80 Appendix B: Notification dated 30.10.2014 issued by Governor of Maharashtra 82 Appendix C: List of State level laws/regulations on prevention of tribal land alienation and its reformation 87 Abbreviations 93 Source: Census of India 2011 Introduction In Part I of the present compendium, we examine the Fifth Schedule of the Constitution and its various provisions. Article 244 of the Constitution of India read with two Schedules – the Fifth and Sixth Schedules – to the Constitution of India provide special arrangements for areas inhabited by Scheduled Tribes. -

Indian Reservations | the Economist Page 1 of 5

Affirmative action: Indian reservations | The Economist Page 1 of 5 Banyan Asia Affirmative action Indian reservations Jun 29th 2013, 3:56 by A.R. | DELHI It has been a busy week for America's Supreme Court (http://www.economist.com/news/united- states/21580152-contentious-rulings-voting- rights-and-college-admissions-equality- debated) , as it returned rulings on cases regarding not only gay marriage but also affirmative action (to use the American euphemism) in the public universities. Our other blogs have handled those decisions in other (http://www.economist.com/blogs/democracyinamerica/2013/06/affirmative- action) entries (http://www.economist.com/blogs/democracyinamerica/2013/06/affirmative-action- case-0) . Looking ahead to this week two months ago the print edition considered affirmative action from a worldwide perspective. That issue took a very critical line (http://www.economist.com/news/leaders/21576662-governments-should-be-colour- blind-time-scrap-affirmative-action) on the entire phenomenon and paid special attention to examples from America (http://www.economist.com/news/briefing/21576658-first- three-pieces-race-based-preferences-around-world-we-look-americas) , South Africa (http://www.economist.com/news/briefing/21576655-black-economic-empowerment-has- not-worked-well-nor-will-it-end-soon-fools-gold) and Malaysia (http://www.economist.com/news/briefing/21576654-elections-may-could-mark-turning- point-never-ending-policy) . India's experience was judged to be too exceptional—in large part because it does not concern race as such—for consideration in that briefing. But as http://www.economist.com/blogs/banyan/2013/06/affirmative -action/print 8/ 6/ 2013 Affirmative action: Indian reservations | The Economist Page 2 of 5 America's Supremes have remanded the issue to lower courts for a while longer, we thought this would be a fine time to take a look at the case of castes.